Zero Dark Thirty Error

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting for Women Existence in Popular Espionage Movies Salt (2010) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012)

Benita Amalina — Fighting For Women Existence in Popular Espionage Movies Salt (2010) and Zero Dark Thirty (2012) FIGHTING FOR WOMEN EXISTENCE IN POPULAR ESPIONAGE MOVIES SALT (2010) AND ZERO DARK THIRTY (2012) Benita Amalina [email protected] Abstract American spy movies have been considered one of the most profitable genre in Hollywood. These spy movies frequently create an assumption that this genre is exclusively masculine, as women have been made oblivious and restricted to either supporting roles or non-spy roles. In 2010 and 2012, portrayal of women in spy movies was finally changed after the release of Salt and Zero Dark Thirty, in which women became the leading spy protagonists. Through the post-nationalist American Studies perspective, this study discusses the importance of both movies in reinventing women’s identity representation in a masculine genre in response to the evolving American society. Keywords: American women, hegemony, representation, Hollywood, movies, popular culture Introduction The financial success and continuous power of this industry implies that there has been The American movie industry, often called good relations between the producers and and widely known as Hollywood, is one of the main target audience. The producers the most powerful cinematic industries in have been able to feed the audience with the world. In the more recent data, from all products that are suitable to their taste. Seen the movies released in 2012 Hollywood from the movies’ financial revenues as achieved $ 10 billion revenue in North previously mentioned, action movies are America alone, while grossing more than $ proven to yield more revenue thus become 34,7 billion worldwide (Kay, 2013). -

ZERO DARK THIRTY an Original Screenplay by Mark Boal October 3

ZERO DARK THIRTY An Original Screenplay by Mark Boal October 3, 2011 all rights reserved FROM BLACK, VOICES EMERGE-- We hear the actual recorded emergency calls made by World Trade Center office workers to police and fire departments after the planes struck on 9/11, just before the buildings collapsed. TITLE OVER: SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 We listen to fragments from a number of these calls...starting with pleas for help, building to a panic, ending with the caller's grim acceptance that help will not arrive, that the situation is hopeless, that they are about to die. CUT TO: TITLE OVER: TWO YEARS LATER INT. BLACK SITE - INTERROGATION ROOM DANIEL I own you, Ammar. You belong to me. Look at me. This is DANIEL STANTON, the CIA's man in Islamabad - a big American, late 30's, with a long, anarchical beard snaking down to his tattooed neck. He looks like a paramilitary hipster, a punk rocker with a Glock. DANIEL (CONT'D) (explaining the rules) If you don't look at me when I talk to you, I hurt you. If you step off this mat, I hurt you. If you lie to me, I'm gonna hurt you. Now, Look at me. His prisoner, AMMAR, stands on a decaying gym mat, surrounded by four GUARDS whose faces are covered in ski masks. Ammar looks down. Instantly: the guards rush Ammar, punching and kicking. DANIEL (CONT'D) Look at me, Ammar. Notably, one of the GUARDS wearing a ski mask does not take part in the beating. 2. EXT. -

Bigelow Masculinity

Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2011) Article TOUGH GUY IN DRAG? HOW THE EXTERNAL, CRITICAL DISCOURSES SURROUNDING KATHRYN BIGELOW DEMONSTRATE THE WIDER PROBLEMS OF THE GENDER QUESTION. RONA MURRAY, De Montford University ABSTRACT This article argues that the various approaches adopted towards Kathryn Bigelow’s work, and their tendency to focus on a gendered discourse, obscures the wider political discourses these texts contain. In particular, by analysing the representation of masculinity across the films, it is possible to see how the work of this director and her collaborators is equally representative of its cultural context and how it uses the trope of the male body as a site for a dialectical study of the uses and status of male strength within an imperialistically-minded western society. KEYWORDS Counter-cultural, feminism, feminist, gender, masculinity, western. ISSN 1755-9944 1 Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2011) Whether the director Kathryn Bigelow likes it or not, gender has been made to lie at the heart of her work, not simply as it figures in her texts but also as it is used to initiate discussion about her own function/place as an auteur? Her career illustrates how the personal becomes the political not via individual agency but in the way she has come to stand as a particular cultural symbol – as a woman directing men in male-orientated action genres. As this persona has become increasingly loaded with various significances, it has begun to alter the interpretations of her films. -

Woman As a Category / New Woman Hybridity

WiN: The EAAS Women’s Network Journal Issue 1 (2018) The American Woman Warrior: A Transnational Feminist Look at War, Imperialism, and Gender Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet ABSTRACT: This article examines the issue of torture and spectatorship in the film Zero Dark Thirty through the question of how it deploys gender ideologically and rhetorically to mediate and frame the violence it represents. It begins with the controversy the film provoked but focuses specifically on the movie’s representational and aesthetic techniques, especially its self-awareness about being a film about watching torture, and how it positions its audience in relation to these scenes. Issues of spectator identification, sympathy, interpellation, affect (for example, shame) and genre are explored. The fact that the main protagonist of the film is a woman is a key dimension of the cultural work of the film. I argue that the use of a female protagonist in this film is part of a larger trend in which the discourse of feminism is appropriated for politically conservative and antifeminist ends, here the tacit justification of the legally murky world of black sites and ‘enhanced interrogation techniques.’ KEYWORDS: gender; women’s studies; torture; war on terror; Abu Ghraib; spectatorship; neoliberalism; Angela McRobbie; Some of you will recognize my title as alluding to Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior (1975), a fictionalized autobiography in which she evokes the fifth-century Chinese legend of a girl who disguises herself as a man in order to go to war in the place of her frail old father. Kingston’s use of this legend is credited with having popularized the story in the United States and paved the way for the 1998 Disney adaptation. -

Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty Or a Visionary?

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Honors Senior Theses/Projects Student Scholarship 6-1-2016 Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? Courtney Richardson Western Oregon University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Richardson, Courtney, "Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary?" (2016). Honors Senior Theses/Projects. 107. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/honors_theses/107 This Undergraduate Honors Thesis/Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Senior Theses/Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Female Director Takes Hollywood by Storm: Is She a Beauty or a Visionary? By Courtney Richardson An Honors Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation from the Western Oregon University Honors Program Dr. Shaun Huston, Thesis Advisor Dr. Gavin Keulks, Honors Program Director Western Oregon University June 2016 2 Acknowledgements First I would like to say a big thank you to my advisor Dr. Shaun Huston. He agreed to step in when my original advisor backed out suddenly and without telling me and really saved the day. Honestly, that was the most stressful part of the entire process and knowing that he was available if I needed his help was a great relief. Second, a thank you to my Honors advisor Dr. -

The “Genre Bender”: the Creative Leadership of Kathryn Bigelow

THE “GENRE BENDER”: THE CREATIVE LEADERSHIP OF KATHRYN BIGELOW Olga Epitropaki and Charalampos Mainemelis ABSTRACT In the present chapter, we present the case study of the only woman film director who has ever won an Academy Award for Best Director, Kathryn Bigelow. We analyzed 43 written interviews of Kathryn Bigelow that have appeared in the popular press in the period 1988 2013 and outlined eight main themes emerging regarding her exercise ofÀ leadership in the cinematic context. We utilize three theoretical frameworks: (a) paradoxical leadership theory (Lewis, Andriopoulos, & Smith, 2014; Smith & Lewis, 2012); (b) ambidextrous leadership theory (Rosing, Frese, & Bausch, 2011), and (c) role congruity theory (Eagley & Karau, 2002) and show how Bigelow, as a woman artist/leader working in a complex organizational system that emphasizes radical innovation, exercised paradoxical and ambidextrous leadership and challenged Downloaded by Doctor Charalampos Mainemelis At 07:19 09 March 2016 (PT) Leadership Lessons from Compelling Contexts Monographs in Leadership and Management, Volume 8, 275 300 À Copyright r 2016 by Emerald Group Publishing Limited All rights of reproduction in any form reserved ISSN: 1479-3571/doi:10.1108/S1479-357120160000008009 275 276 OLGA EPITROPAKI AND CHARALAMPOS MAINEMELIS existing conventions about genre, gender, and leadership. The case study implications for teaching and practice are discussed. Keywords: Creative leadership; ambidextrous leadership; paradoxical leadership; role congruity theory; director; film industry She’s acting out desires. She represents what people want to see, and it’s upsetting, because they don’t know exactly what to do with it. Cultural theorist Sylve´ re Lotringer INTRODUCTION Organizations are abounding with tensions and conflicting demands (e.g., flexibility vs. -

Blurring the Boundaries: Auteurism & Kathryn Bigelow Brenda Wilson

Blurring the Boundaries: Auteurism & Kathryn Bigelow Brenda Wilson Born in California in 1952, Katherine Bigelow is one of group of outsiders living by different rules are presented the few women directors working in Hollywood today. She here as whole- heartedly cool. And the aesthetic style of is exceptional because she works primarily within the the film is indicative of Bigelow's increasingly idiosyncratic traditionally male- dominated genres of the action cinema. choices that create arresting images and innovative action Bigelow's films often reflect a different approach to these sequences. Strange Days (1995) is the film in Bigelow's genres as she consistently explores themes of violence, oeuvre that has received the most critical and theoretical voyeurism and sexual politics. Ultimately she seems to be attention, and so for the purposes of this analysis it will be concerned with calling the boundaries between particular referred to but not fully theorized. Strange Days is a neo- genres into question. Bigelow's visual style echoes this noir science fiction film that presents the future on the eve thematic complexity, often introducing elements of an art- of the new millennium, a dystopic Los Angeles which is on house aesthetic. Bigelow emerged from the New York art the verge of erupting into a race war. The film was a critical scene in the 1970s, having won a Whitney Scholarship to if not commercial success, building upon recognizable study painting. She later transferred to the Columbia Film Bigelow motifs. The film is a rich tapestry of narrative program. Critics such as Yvonne Tasker have commented threads, stunning visuals and soundtrack, all of which on the amalgamation of spectacle and adrenaline with compete for attention. -

Announcing a VIEW from the BRIDGE

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE “One of the most powerful productions of a Miller play I have ever seen. By the end you feel both emotionally drained and unexpectedly elated — the classic hallmark of a great production.” - The Daily Telegraph “To say visionary director Ivo van Hove’s production is the best show in the West End is like saying Stonehenge is the current best rock arrangement in Wiltshire; it almost feels silly to compare this pure, primal, colossal thing with anything else on the West End. A guileless granite pillar of muscle and instinct, Mark Strong’s stupendous Eddie is a force of nature.” - Time Out “Intense and adventurous. One of the great theatrical productions of the decade.” -The London Times DIRECT FROM TWO SOLD-OUT ENGAGEMENTS IN LONDON YOUNG VIC’S OLIVIER AWARD-WINNING PRODUCTION OF ARTHUR MILLER’S “A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE” Directed by IVO VAN HOVE STARRING MARK STRONG, NICOLA WALKER, PHOEBE FOX, EMUN ELLIOTT, MICHAEL GOULD IS COMING TO BROADWAY THIS FALL PREVIEWS BEGIN WEDNESDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 21 OPENING NIGHT IS THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 12 AT THE LYCEUM THEATRE Direct from two completely sold-out engagements in London, producers Scott Rudin and Lincoln Center Theater will bring the Young Vic’s critically-acclaimed production of Arthur Miller’s A VIEW FROM THE BRIDGE to Broadway this fall. The production, which swept the 2015 Olivier Awards — winning for Best Revival, Best Director, and Best Actor (Mark Strong) —will begin previews Wednesday evening, October 21 and open on Thursday, November 12 at the Lyceum Theatre, 149 West 45 Street. -

A Look at the Forthcoming Remake of Point Break | DIY

10/28/2015 A look at the forthcoming remake of Point Break | DIY PREVIEW: A LOOK AT THE FORTHCOMING REMAKE OF POINT BREAK This week, DIY were among the very first people in the world to see footage from the upcoming Point Break. By Christa Ktorides on 27th October 2015 This week, DIY were among the very first people in the world to see footage from the upcoming Point Break, the highly anticipated remake of the http://diymag.com/2015/10/27/a-look-at-the-forthcoming-remake-of-point-break 1/6 10/28/2015 A look at the forthcoming remake of Point Break | DIY 1991 action classic courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Screening in the rather luxurious new Picturehouse Central in London, we’re treated to some extended scenes of the unfinished film in the company of director Ericson Core, star Édgar Ramírez and renowned extreme athletes Xavier De Le Rue and Chris Sharma. So why re-make the cult film now? Core explains: “Pretty much every one of our extreme athletes who participated in the film came to it because they were highly influenced by the original film and pursued their various sports partially charged with that sort of spirit of that original film. Ramírez for his part reveals a long-standing relationship with the original Keanu Reeves/Patrick Swayze starrer: “I belong to the generation of the first one, I was 13 years old when that came out. I was very attracted to the movie, very inspired by it. Little did I know that eventually, a few years later I would be playing Bodhi which was definitely the character I was impressed by.” First up we’re shown the opening sequence of the film where YouTube superstar and extreme motorcross rider, Johnny Utah (Luke Bracey) is performing a seemingly impossible stunt for the cameras with his friend Jeff (Max Thieriot). -

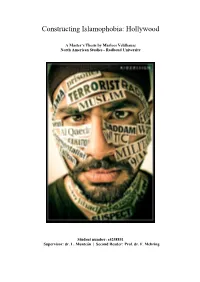

Constructing Islamophobia: Hollywood

Constructing Islamophobia: Hollywood A Master’s Thesis by Marloes Veldhausz North American Studies - Radboud University Student number: s4258851 Supervisor: dr. L. Munteán | Second Reader: Prof. dr. F. Mehring Veldhausz 4258851/2 Abstract Islam has become highly politicized post-9/11, the Islamophobia that has followed has been spread throughout the news media and Hollywood in particular. By using theories based on stereotypes, Othering, and Orientalism and a methodology based on film studies, in particular mise-en-scène, the way in which Islamophobia has been constructed in three case studies has been examined. These case studies are the following three Hollywood movies: The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, and American Sniper. Derogatory rhetoric and mise-en-scène aspects proved to be shaping Islamophobia. The movies focus on events that happened post- 9/11 and the ideological markers that trigger Islamophobia in these movies are thus related to the opinions on Islam that have become widespread throughout Hollywood and the media since; examples being that Muslims are non-compatible with Western societies, savages, evil, and terrorists. Keywords: Islam, Muslim, Arab, Islamophobia, Religion, Mass Media, Movies, Hollywood, The Hurt Locker, Zero Dark Thirty, American Sniper, Mise-en-scène, Film Studies, American Studies. 2 Veldhausz 4258851/3 To my grandparents, I can never thank you enough for introducing me to Harry Potter and thus bringing magic into my life. 3 Veldhausz 4258851/4 Acknowledgements Thank you, first and foremost, to dr. László Munteán, for guiding me throughout the process of writing the largest piece of research I have ever written. I would not have been able to complete this daunting task without your help, ideas, patience, and guidance. -

European Journal of American Studies, 12-2 | 2017 “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Gl

European journal of American studies 12-2 | 2017 Summer 2017, including Special Issue: Popularizing Politics: The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre Lennart Soberon Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12086 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12086 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Lennart Soberon, ““The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre”, European journal of American studies [Online], 12-2 | 2017, document 12, Online since 01 August 2017, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ ejas/12086 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.12086 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Gl... 1 “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre Lennart Soberon 1 While recent years have seen no shortage of American action thrillers dealing with the War on Terror—Act of Valor (2012), Zero Dark Thirty (2012), and Lone Survivor (2013) to name just a few examples—no film has been met with such a great controversy as well as commercial success as American Sniper (2014). Directed by Clint Eastwood and based on the autobiography of the most lethal sniper in U.S. military history, American Sniper follows infamous Navy Seal Chris Kyle throughout his four tours of duty to Iraq. -

Unclassified Fictions: the CIA, Secrecy Law, and the Dangerous Rhetoric of Authenticity

Unclassified Fictions: The CIA, Secrecy Law, and the Dangerous Rhetoric of Authenticity Matthew H. Birkhold* ABSTRACT Zero Dark Thirty , Kathryn Bigelow’s cinematic account of the manhunt for Osama bin Laden, attracted tremendous popular attention, inspiring impassioned debates about torture, political access, and responsible filmmaking. But, in the aftermath of the 2013 Academy Awards, critical scrutiny of the film has abated and the Senate has dropped its much-hyped inquiry. If the discussion about Zero Dark Thirty ultimately proved fleeting, our attention to the circumstances of its creation should not. The CIA has a longstanding policy of promoting the accuracy of television shows and films that portray the agency, and Langley’s collaboration with Bigelow provided no exception. To date, legal scholarship has largely ignored the CIA’s policy, yet the practice of assisting filmmakers has important consequences for national security law. Recently, the CIA’s role in Zero Dark Thirty’s creation and the agency’s refusal to release authentic images of the deceased Osama bin Laden reveals its attitude toward fiction and how it impacts the CIA’s legal justifications for secrecy. By conducting a close analysis of CIA affidavits submitted in FOIA litigation and recently declassified records detailing the CIA’s interactions with Bigelow, this article demonstrates how films like Zero Dark Thirty function as workarounds where the underlying records are classified. These films are “unclassified fictions” in that they allow the CIA to preserve the secrecy of classified records by communicating nearly identical information to the public. Unclassified fictions, in other words, allow the CIA to evade secrecy while maintaining that secrecy—to speak without speaking.