Biodiversity of Scottish Wildlife Trust Reserves (2011)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fauna Lepidopterologica Volgo-Uralensis" 150 Years Later: Changes and Additions

©Ges. zur Förderung d. Erforschung von Insektenwanderungen e.V. München, download unter www.zobodat.at Atalanta (August 2000) 31 (1/2):327-367< Würzburg, ISSN 0171-0079 "Fauna lepidopterologica Volgo-Uralensis" 150 years later: changes and additions. Part 5. Noctuidae (Insecto, Lepidoptera) by Vasily V. A n ik in , Sergey A. Sachkov , Va d im V. Z o lo t u h in & A n drey V. Sv ir id o v received 24.II.2000 Summary: 630 species of the Noctuidae are listed for the modern Volgo-Ural fauna. 2 species [Mesapamea hedeni Graeser and Amphidrina amurensis Staudinger ) are noted from Europe for the first time and one more— Nycteola siculana Fuchs —from Russia. 3 species ( Catocala optata Godart , Helicoverpa obsoleta Fabricius , Pseudohadena minuta Pungeler ) are deleted from the list. Supposedly they were either erroneously determinated or incorrect noted from the region under consideration since Eversmann 's work. 289 species are recorded from the re gion in addition to Eversmann 's list. This paper is the fifth in a series of publications1 dealing with the composition of the pres ent-day fauna of noctuid-moths in the Middle Volga and the south-western Cisurals. This re gion comprises the administrative divisions of the Astrakhan, Volgograd, Saratov, Samara, Uljanovsk, Orenburg, Uralsk and Atyraus (= Gurjev) Districts, together with Tataria and Bash kiria. As was accepted in the first part of this series, only material reliably labelled, and cover ing the last 20 years was used for this study. The main collections are those of the authors: V. A n i k i n (Saratov and Volgograd Districts), S. -

Climate Change and Conservation of Orophilous Moths at the Southern Boundary of Their Range (Lepidoptera: Macroheterocera)

Eur. J. Entomol. 106: 231–239, 2009 http://www.eje.cz/scripts/viewabstract.php?abstract=1447 ISSN 1210-5759 (print), 1802-8829 (online) On top of a Mediterranean Massif: Climate change and conservation of orophilous moths at the southern boundary of their range (Lepidoptera: Macroheterocera) STEFANO SCALERCIO CRA Centro di Ricerca per l’Olivicoltura e l’Industria Olearia, Contrada Li Rocchi-Vermicelli, I-87036 Rende, Italy; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Biogeographic relict, extinction risk, global warming, species richness, sub-alpine prairies Abstract. During the last few decades the tree line has shifted upward on Mediterranean mountains. This has resulted in a decrease in the area of the sub-alpine prairie habitat and an increase in the threat to strictly orophilous moths that occur there. This also occurred on the Pollino Massif due to the increase in temperature and decrease in rainfall in Southern Italy. We found that a number of moths present in the alpine prairie at 2000 m appear to be absent from similar habitats at 1500–1700 m. Some of these species are thought to be at the lower latitude margin of their range. Among them, Pareulype berberata and Entephria flavicinctata are esti- mated to be the most threatened because their populations are isolated and seem to be small in size. The tops of these mountains are inhabited by specialized moth communities, which are strikingly different from those at lower altitudes on the same massif further south. The majority of the species recorded in the sub-alpine prairies studied occur most frequently and abundantly in the core area of the Pollino Massif. -

List of Vascular Plants Endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands 2020

British & Irish Botany 2(3): 169-189, 2020 List of vascular plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands 2020 Timothy C.G. Rich Cardiff, U.K. Corresponding author: Tim Rich: [email protected] This pdf constitutes the Version of Record published on 31st August 2020 Abstract A list of 804 plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands is broken down by country. There are 659 taxa endemic to Britain, 20 to Ireland and three to the Channel Islands. There are 25 endemic sexual species and 26 sexual subspecies, the remainder are mostly critical apomictic taxa. Fifteen endemics (2%) are certainly or probably extinct in the wild. Keywords: England; Northern Ireland; Republic of Ireland; Scotland; Wales. Introduction This note provides a list of vascular plants endemic to Britain, Ireland and the Channel Islands, updating the lists in Rich et al. (1999), Dines (2008), Stroh et al. (2014) and Wyse Jackson et al. (2016). The list includes endemics of subspecific rank or above, but excludes infraspecific taxa of lower rank and hybrids (for the latter, see Stace et al., 2015). There are, of course, different taxonomic views on some of the taxa included. Nomenclature, taxonomic rank and endemic status follows Stace (2019), except for Hieracium (Sell & Murrell, 2006; McCosh & Rich, 2018), Ranunculus auricomus group (A. C. Leslie in Sell & Murrell, 2018), Rubus (Edees & Newton, 1988; Newton & Randall, 2004; Kurtto & Weber, 2009; Kurtto et al. 2010, and recent papers), Taraxacum (Dudman & Richards, 1997; Kirschner & Štepànek, 1998 and recent papers) and Ulmus (Sell & Murrell, 2018). Ulmus is included with some reservations, as many taxa are largely vegetative clones which may occasionally reproduce sexually and hence may not merit species status (cf. -

Condition of Designated Sites

Scottish Natural Heritage Condition of Designated Sites Contents Chapter Page Summary ii Condition of Designated Sites (Progress to March 2010) Site Condition Monitoring 1 Purpose of SCM 1 Sites covered by SCM 1 How is SCM implemented? 2 Assessment of condition 2 Activities and management measures in place 3 Summary results of the first cycle of SCM 3 Action taken following a finding of unfavourable status in the assessment 3 Natural features in Unfavourable condition – Scottish Government Targets 4 The 2010 Condition Target Achievement 4 Amphibians and Reptiles 6 Birds 10 Freshwater Fauna 18 Invertebrates 24 Mammals 30 Non-vascular Plants 36 Vascular Plants 42 Marine Habitats 48 Coastal 54 Machair 60 Fen, Marsh and Swamp 66 Lowland Grassland 72 Lowland Heath 78 Lowland Raised Bog 82 Standing Waters 86 Rivers and Streams 92 Woodlands 96 Upland Bogs 102 Upland Fen, Marsh and Swamp 106 Upland Grassland 112 Upland Heathland 118 Upland Inland Rock 124 Montane Habitats 128 Earth Science 134 www.snh.gov.uk i Scottish Natural Heritage Summary Background Scotland has a rich and important diversity of biological and geological features. Many of these species populations, habitats or earth science features are nationally and/ or internationally important and there is a series of nature conservation designations at national (Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)), European (Special Area of Conservation (SAC) and Special Protection Area (SPA)) and international (Ramsar) levels which seek to protect the best examples. There are a total of 1881 designated sites in Scotland, although their boundaries sometimes overlap, which host a total of 5437 designated natural features. -

Download List of Notable Species in Edinburgh

Group Scientific name Common name International / UK status Scottish status Lothian status marine mammal Balaenoptera acutorostrata Minke Whale HSD PS W5 SBL SO1 marine mammal Delphinus delphis Common Dolphin Bo HSD PS W5 SBL SO1 marine mammal Halichoerus grypus Grey Seal Bo HSD marine mammal Lagenorhynchus albirostris White-beaked Dolphin Bo HSD PS W5 SBL SO1 marine mammal Phocoena phocoena Common Porpoise Bo GVU HSD PS W5 SBL SO1 marine mammal Tursiops truncatus Bottle-Nosed Dolphin Bo HSD PS W5 SBL SO1 terrestrial mammal Arvicola terrestris European Water Vole PS W5 SBL Sc5 terrestrial mammal Erinaceus europaeus West European Hedgehog PS terrestrial mammal Lepus europaeus Brown Hare PS SBL Sc5 terrestrial mammal Lepus timidus Mountain Hare HSD PS SBL Sc5 terrestrial mammal Lutra lutra European Otter HSD PS W5 SBL SO1 terrestrial mammal Meles meles Eurasian Badger BA SBL SO1 terrestrial mammal Micromys minutus Harvest Mouse PS E? terrestrial mammal Myotis daubentonii Daubenton's Bat Bo HSD W5 SBL terrestrial mammal Myotis nattereri Natterer's Bat Bo HSD W5 SBL terrestrial mammal Pipistrellus pipistrellus Pipistrellus pipistrellus Bo HSD W5 terrestrial mammal Pipistrellus pygmaeus Soprano Pipistrelle PS SBL terrestrial mammal Plecotus auritus Brown Long-eared Bat Bo HSD PS W5 SBL terrestrial mammal Sciurus vulgaris Eurasian Red Squirrel PS W5 SBL SO1 bird Accipiter nisus Eurasian Sparrowhawk Bo bird Actitis hypoleucos Common Sandpiper Bo bird Alauda arvensis Sky Lark BCR BD SBL bird Alcedo atthis Common Kingfisher BCA W1 SBL bird Anas -

Lepidoptera in Cheshire in 2002

Lepidoptera in Cheshire in 2002 A Report on the Micro-Moths, Butterflies and Macro-Moths of VC58 S.H. Hind, S. McWilliam, B.T. Shaw, S. Farrell and A. Wander Lancashire & Cheshire Entomological Society November 2003 1 1. Introduction Welcome to the 2002 report on lepidoptera in VC58 (Cheshire). This is the second report to appear in 2003 and follows on from the release of the 2001 version earlier this year. Hopefully we are now on course to return to an annual report, with the 2003 report planned for the middle of next year. Plans for the ‘Atlas of Lepidoptera in VC58’ continue apace. We had hoped to produce a further update to the Atlas but this report is already quite a large document. We will, therefore produce a supplementary report on the Pug Moths recorded in VC58 sometime in early 2004, hopefully in time to be sent out with the next newsletter. As usual, we have produced a combined report covering micro-moths, macro- moths and butterflies, rather than separate reports on all three groups. Doubtless observers will turn first to the group they are most interested in, but please take the time to read the other sections. Hopefully you will find something of interest. Many thanks to all recorders who have already submitted records for 2002. Without your efforts this report would not be possible. Please keep the records coming! This request also most definitely applies to recorders who have not sent in records for 2002 or even earlier. It is never too late to send in historic records as they will all be included within the above-mentioned Atlas when this is produced. -

Buletinul Известия Journal

Buletinul AŞM. Ştiinţele vieţii. Nr. 3(330) 2016 Buletinul AŞM. Ştiinţele vieţii. Nr. 3(330) 2016 ISSN 1857-064X Categoria B BULETINUL ACADEMIEI DE ŞTIINŢE A MOLDOVEI Ştiinţele vieţii ИЗВЕСТИЯ АКАДЕМИИ НАУК МОЛДОВЫ Науки о жизНи JOURNAL OF ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF MOLDOVA LIFE SCIENCES 3 (330) 2016 Chişinău Buletinul AŞM. Ştiinţele vieţii. Nr. 3(330) 2016 Buletinul AŞM. Ştiinţele vieţii. Nr. 3(330) 2016 COLEGIUL DE REDACŢIE Redactor-şef Valentina CIOCHINĂ Teodor FURDUI Institutul de Fiziologie şi Sanocreatologie al Aca- Institutul de Fiziologie şi Sanocreatologie al Aca- demiei de Ştiinţe a Moldovei, Laboratorul Fiziolo- demiei de Ştiinţe a Moldovei, Laboratorul Fiziolo- gia stresului, adaptării şi Sanocreatologie generală, gia stresului, adaptării şi Sanocreatologie generală, doctor, conferenţiar. Adresa: str. Academiei, 1, MD- academician, doctor habilitat, profesor. Adresa: str. 2028 Chişinău, Republica Moldova. Tel.: (+373)22 Academiei, 1, MD-2028 Chişinău, Republica Mol- 725152; E-mail: [email protected] dova. Tel.: (+373)22 725209; (+373) 069972538 Gheorghe DUCA Redactor-şef adjunct Institutul de Chimie al Academiei de Ştiinţe a Moldovei, Centrul Chimie Fizică şi Nanocompozite, Ion TODERAŞ academician, doctor habilitat, profesor. Adresa: Institutul de Zoologie al Academiei de Ştiinţe bd.Ştefan cel Mare, 1, MD-2001 Chişinău, a Moldovei, Centrul de Cercetare a Invaziilor Republica Moldova. Tel/Fax.: (+373)22 271478; Biologice, Laboratorul de Sistematică şi Filogenie E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] moleculară, academician, doctor habilitat, profesor. Adresa: str. Academiei, 1, MD-2028 Chişinău, Maria DUCA Republica Moldova. Tel.: (+373)22 731255; Universitatea Academiei de Ştiinţe a Moldovei, E-mail:[email protected] Centrul universitar Genetică funcţională, Secretar responsabil academician, doctor habilitat, profesor. -

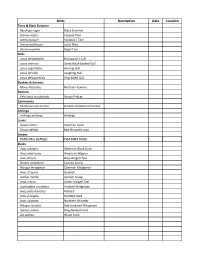

Bird Species Check List

Birds Description Date Location Terns & Black Skimmer Rynchops niger Black Skimmer Sterna caspia Caspian Tern Stema forsteri Forester's Tern Sterna antillarum Least Tern Sterna maxima Royal Tern Gulls Larus philadelphia Bonaparte's Gull Larus marinus Great Black‐backed Gull Larus argentatus Herring Gull Larus atricilla Laughing Gull Larus delawarensis Ring‐billed Gull Boobies & Gannets Morus bassanus Northern Gannet Pelicans Pelecanus occidentalis Brown Pelican Cormorants Phalacrocorax auritus Double‐Crested Cormorant Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Anhinga Loons Gavia immer Common Loon Gavia stellata Red‐throated Loon Grebes PodilymbusPodil ymbus popodicepsdiceps PiPieded‐billbilleded GrebeGrebe Ducks Anas rubripes American Black Duck Anas americana American Wigeon Anas discors Blue‐winged Teal Branta canadensis Canada Goose Mergus merganser Common Merganser Anas strepera Gadwall Aythya marila Greater Scaup Anas crecca Green‐winged Teal Lophodytes cucullatus Hooded Merganser Anas platyrhynchos Mallard Anas fulvigula Mottled Duck Anas clypeata Northern Shoveler Mergus serrator Red‐breasted Merganser Aythya collaris Ring‐Necked Duck Aix sponsa Wood Duck Birds Description Date Location Rails & Northern Jacana Fulica americana American Coot Rallus longirostris Clapper Rail Gallinula chloropus Common Moorhen Rallus elegans King Rail Porzana carolina Sora Long‐legged Waders Nycticorax nycticorax Black‐crowned Night‐Heron Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret Plegadis falcinellus Glossy Ibis Ardea herodias Great Blue Heron Casmerodius albus Great Egret Butorides -

Zoogeography of the Holarctic Species of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera): Importance of the Bering Ian Refuge

© Entomologica Fennica. 8.XI.l991 Zoogeography of the Holarctic species of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera): importance of the Bering ian refuge Kauri Mikkola, J, D. Lafontaine & V. S. Kononenko Mikkola, K., Lafontaine, J.D. & Kononenko, V. S. 1991 : Zoogeography of the Holarctic species of the Noctuidae (Lepidoptera): importance of the Beringian refuge. - En to mol. Fennica 2: 157- 173. As a result of published and unpublished revisionary work, literature compi lation and expeditions to the Beringian area, 98 species of the Noctuidae are listed as Holarctic and grouped according to their taxonomic and distributional history. Of the 44 species considered to be "naturall y" Holarctic before this study, 27 (61 %) are confirmed as Holarctic; 16 species are added on account of range extensions and 29 because of changes in their taxonomic status; 17 taxa are deleted from the Holarctic list. This brings the total of the group to 72 species. Thirteen species are considered to be introduced by man from Europe, a further eight to have been transported by man in the subtropical areas, and five migrant species, three of them of Neotropical origin, may have been assisted by man. The m~jority of the "naturally" Holarctic species are associated with tundra habitats. The species of dry tundra are frequently endemic to Beringia. In the taiga zone, most Holarctic connections consist of Palaearctic/ Nearctic species pairs. The proportion ofHolarctic species decreases from 100 % in the High Arctic to between 40 and 75 % in Beringia and the northern taiga zone, and from between 10 and 20 % in Newfoundland and Finland to between 2 and 4 % in southern Ontario, Central Europe, Spain and Primorye. -

England Biodiversity Indicators 2020

4a. Status of UK priority species: relative abundance England Biodiversity Indicators 2020 This documents supports 4a. Status of UK priority species: relative abundance Technical background document Fiona Burns, Tom August, Mark Eaton, David Noble, Gary Powney, Nick Isaac, Daniel Hayhow For further information on 4a. Status of UK priority species: relative abundance visit https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/england-biodiversity-indicators 1 4a. Status of UK priority species: relative abundance Indicator 4a. Status of UK priority species: relative abundance Technical background document, 2020 NB this paper should be read together with 4b Status of UK Priority Species; distribution which presents a companion statistic based on time series on frequency of occurrence (distribution) of priority species. 1. Introduction The adjustments to the UK biodiversity indicators set as a result of the adoption of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity (including the Aichi Targets) at the 10th Conference of Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity mean there is a need to report progress against Aichi Target 12: Target 12: By 2020 the extinction of known threatened species has been prevented and their conservation status, particularly of those most in decline, has been improved and sustained. Previously, the UK biodiversity indicator for threatened species used lead partner status assessments on the status of priority species from 3-yearly UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP) reporting rounds. As a result of the devolution of biodiversity strategies to the UK's 4 nations, there is no longer reporting at the UK level of the status of species previously listed by the BAP process. This paper presents a robust indicator of the status of threatened species in the UK, with species identified as conservation priorities being taken as a proxy for threatened species. -

Recording and Monitoring Rarer Moths in the Yorkshire Dales

WHITAKER (2015). FIELD STUDIES (http://fsj.field-studies-council.org/) RECORDING AND MONITORING RARER MOTHS IN THE YORKSHIRE DALES TERRY WHITAKER [email protected] Field notes on some of the Yorkshire Dales National Park’s rarer moths, and the activity of the Yorkshire Dales Butterfly and Moth Action Group in increasing our KnoWledge of their distribution and status. RESEARCH SUMMARY Yorkshire Dales Butterfly and Moth Action Group YorKshire Dales Butterfly and Moth Action Group (YDBMAG) started in 2002 as an initiative betWeen Butterfly Conservation, the YorKshire Naturalists’ Union and the YorKshire Dales National ParK Authority (YDNPA). Its aims and objectives are as folloWs: • To advise on habitat action plans affecting Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP) Lepidoptera; • To devise species action plans for Local Biodiversity Action Plan (LBAP) Lepidoptera; • To monitor LBAP lepidopteran species. The folloWing initiatives have been promoted: • Increase public aWareness of LBAP species; • Increase KnoWledge of distribution of LBAP butterfly species; • Set up butterfly monitoring transects for LBAP species. These initiatives have included: • Setting up transects for small pearl-bordered fritillary and northern brown argus butterflies; • Surveys to discover the status and distribution in the YorKshire Dales National ParK (YDNP) of small pearl- bordered fritillary butterfly 2002, 2007-8 and 2013 and northern broWn argus butterfly 2002, 2007 and 2013; • Producing reporting postcards for common blue and green hairstreaK butterflies (2005-2007; 2006-2007); • Producing an identification guide to butterflies in the YDNP, With English Nature (WhitaKer, 2004); • Setting up transects in the small pearl-bordered fritillary and northern brown argus butterfly in the YDNP, by 2003. Currently, (2013), there are six UK butterfly monitoring scheme (UKBMS) transects in the YDNP. -

MOTHS and BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed Distributional Information Has Been J.D

MOTHS AND BUTTERFLIES LEPIDOPTERA DISTRIBUTION DATA SOURCES (LEPIDOPTERA) * Detailed distributional information has been J.D. Lafontaine published for only a few groups of Lepidoptera in western Biological Resources Program, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada. Scott (1986) gives good distribution maps for Canada butterflies in North America but these are generalized shade Central Experimental Farm Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0C6 maps that give no detail within the Montane Cordillera Ecozone. A series of memoirs on the Inchworms (family and Geometridae) of Canada by McGuffin (1967, 1972, 1977, 1981, 1987) and Bolte (1990) cover about 3/4 of the Canadian J.T. Troubridge fauna and include dot maps for most species. A long term project on the “Forest Lepidoptera of Canada” resulted in a Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre (Agassiz) four volume series on Lepidoptera that feed on trees in Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada Canada and these also give dot maps for most species Box 1000, Agassiz, B.C. V0M 1A0 (McGugan, 1958; Prentice, 1962, 1963, 1965). Dot maps for three groups of Cutworm Moths (Family Noctuidae): the subfamily Plusiinae (Lafontaine and Poole, 1991), the subfamilies Cuculliinae and Psaphidinae (Poole, 1995), and ABSTRACT the tribe Noctuini (subfamily Noctuinae) (Lafontaine, 1998) have also been published. Most fascicles in The Moths of The Montane Cordillera Ecozone of British Columbia America North of Mexico series (e.g. Ferguson, 1971-72, and southwestern Alberta supports a diverse fauna with over 1978; Franclemont, 1973; Hodges, 1971, 1986; Lafontaine, 2,000 species of butterflies and moths (Order Lepidoptera) 1987; Munroe, 1972-74, 1976; Neunzig, 1986, 1990, 1997) recorded to date.