Reproduction and Survival in a Declining Population of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

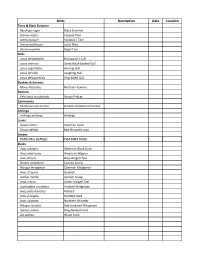

Bird Species Check List

Birds Description Date Location Terns & Black Skimmer Rynchops niger Black Skimmer Sterna caspia Caspian Tern Stema forsteri Forester's Tern Sterna antillarum Least Tern Sterna maxima Royal Tern Gulls Larus philadelphia Bonaparte's Gull Larus marinus Great Black‐backed Gull Larus argentatus Herring Gull Larus atricilla Laughing Gull Larus delawarensis Ring‐billed Gull Boobies & Gannets Morus bassanus Northern Gannet Pelicans Pelecanus occidentalis Brown Pelican Cormorants Phalacrocorax auritus Double‐Crested Cormorant Anhinga Anhinga anhinga Anhinga Loons Gavia immer Common Loon Gavia stellata Red‐throated Loon Grebes PodilymbusPodil ymbus popodicepsdiceps PiPieded‐billbilleded GrebeGrebe Ducks Anas rubripes American Black Duck Anas americana American Wigeon Anas discors Blue‐winged Teal Branta canadensis Canada Goose Mergus merganser Common Merganser Anas strepera Gadwall Aythya marila Greater Scaup Anas crecca Green‐winged Teal Lophodytes cucullatus Hooded Merganser Anas platyrhynchos Mallard Anas fulvigula Mottled Duck Anas clypeata Northern Shoveler Mergus serrator Red‐breasted Merganser Aythya collaris Ring‐Necked Duck Aix sponsa Wood Duck Birds Description Date Location Rails & Northern Jacana Fulica americana American Coot Rallus longirostris Clapper Rail Gallinula chloropus Common Moorhen Rallus elegans King Rail Porzana carolina Sora Long‐legged Waders Nycticorax nycticorax Black‐crowned Night‐Heron Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret Plegadis falcinellus Glossy Ibis Ardea herodias Great Blue Heron Casmerodius albus Great Egret Butorides -

Breeding Schedule and Primary Moult in Dunlins <I>Calidris Alpina</I> Of

29 Breeding scheduleand primary moult in Dunlins Calidris alpina of the Far East Panel S. Tomkoich Tomkovich,P.S. 1998. Breedingschedule and primarymoult in Dunlins Calidris alpina of the Far East. WaderStudy Group Bull. 85:29-34 On Chukotka,the breedinggrounds of the subspeciessakhalina, the primarymoult of Dunlin Calidrisalpina startsin mid-June,at the beginningof theincubation period, and birds migrate southward from thebeginning of August,when the moultis almostcomplete. On Kamchatka(kistchinski) and Sakhalin(actites), where breeding takes place earlier, primary moult startsin July,in the chick rearing period,or evenlater. Thesedifferences between northern and southern populations are similarto thosefound previously in Alaska (Holmes1971). The timing of theseevents is not strictlyrelated to latitude; it is thoughtthat, with localvariations, latitudinal differencesin datesof breedingand primary moult are brought about through subspecific characteristics. Knowledge of subspecific breedingschedules and primary moult periods can be usedtogether with biometricsto assignFar EasternDunlins to different populationsin the post-breedingperiod. P S. Tomkovich,Zoological Museum, Moscow Lomonosov State University,Bolshaya Nikitskaya Street 6, Moscow103009, Russia. INTRODUCTION Far East are comparedin this study. Two new subspeciesof Dunlin from the Far East, Calidris alpina kistchinski(Tornkovich 1986) and C.a. actites(Nechaev STUDY AREAS AND METHODS & Tornkovich1987, 1988), were describedrecently, in The main data were collectedduring expeditions -

Peeps and Related Sandpipers Peeps Are a Group of Diminutive Sandpipers That Are Notoriously Hard to Tell Apart

Peeps and Related Sandpipers Peeps are a group of diminutive sandpipers that are notoriously hard to tell apart. They belong to a subfamily of subarctic and arctic nesting sandpipers known as the Calidridinae (in the sandpiper family, Scolopacidae). During their migrations, when most residents of North America have the opportunity to watch them, mixed flocks of calidridine sandpipers scurry about on mudflats, feeding at the edge of the retreating tide, or swarm aloft, twisting and turning like a dense school of fish. These traits, in a group of birds that look so much alike to start with, give bird watchers nightmares. Fortunately for Alaskans and visitors to our state, Alaska is an excellent location to view and identify calidridine sandpipers. The early summer breeding season is the easiest time of the year to distinguish the various species, not only because they are in breeding plumage and are more approachable than at other times of the year, but also because each species performs a characteristic courtship display with unique vocalizations. For the avid birder, Alaska has the additional attraction of being one of the best places in North America to view exotic Eurasian species. General description: Three peeps are abundant summer residents and breeders in Alaska—the least, semipalmated, and western sandpipers (Calidris minutilla, C. pusilla, and C. mauri) [all lists in order by size]. Another four species from Eurasia may also be seen—the little, rufous-necked, Temminck's, and long-toed stints (“stint” is the British equivalent for peep) (C. minuta, C. ruficollis, C. temminckii, C. subminuta). These seven species range from 5 to 6½ inches (15-17 cm) in length, and weigh from 2/3 to 1½ ounces (17-33 g). -

Shorebirds and Horseshoe Crabs in Jamaica Bay: 2014 Update

Shorebirds and Horseshoe Crabs in Jamaica Bay: 2014 Update credit: Don Riepe Debra Kriensky, New York City Audubon Harbor Herons Working Group Annual Meeting –Dec. 11‐12, 2014 Photo Credit: coastaloutdooradventures.com Sanderling Ruddy Turnstone Red Knot Shorebird Migration Semipalmated Sandpiper Dunlin http://fossilcollector.wordpress.com/ Photo Credit: marinebio.org www.allposters.com Jamaica Bay JBWR Big Egg Marsh Plumb Beach Dead Horse Bay Bay Dunes Shorebird monitoring sites Horseshoe crab monitoring sites CITIZEN SCIENCE Horseshoe Crab Monitoring 2009‐2014 Average # of HSC Counted per Sampling Night 350 Note: Different sampling methods 300 used at PBW & DHB in 2014 Night 250 Sampling per 200 Plumb Beach Dead Horse Bay Counted 150 Big Egg Marsh HSC Plumb Beach West of # 100 Average 50 0 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Year Plumb Beach June 2012 vs. November 2012 Shorebird Monitoring 2009‐2014 Maximum Count per Species ‐ Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge 3000 2500 American Oystercatcher Black‐bellied Plover 2000 Dunlin Least Sandpiper Red Knot 1500 Ruddy Turnstone Sanderling Semipalmated Plover 1000 Semipalmated Sandpiper Short‐billed Dowitcher White‐rumped Sandpiper 500 Willet 0 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 Shorebird Monitoring 2009‐2014 Maximum Count per Species ‐ Plumb Beach 3500 3000 American Oystercatcher Black‐bellied Plover 2500 Dunlin Least Sandpiper Red Knot 2000 Ruddy Turnstone Sanderling 1500 Semipalmated Plover Semipalmated Sandpiper Short‐billed Dowitcher 1000 White‐rumped Sandpiper Willet 500 TOTAL HSC 0 2009 2010 2011 2012 -

Red List of Bangladesh 2015

Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary Chief National Technical Expert Mohammad Ali Reza Khan Technical Coordinator Mohammad Shahad Mahabub Chowdhury IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Bangladesh Country Office 2015 i The designation of geographical entitles in this book and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature concerning the legal status of any country, territory, administration, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The biodiversity database and views expressed in this publication are not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Bangladesh Forest Department and The World Bank. This publication has been made possible because of the funding received from The World Bank through Bangladesh Forest Department to implement the subproject entitled ‘Updating Species Red List of Bangladesh’ under the ‘Strengthening Regional Cooperation for Wildlife Protection (SRCWP)’ Project. Published by: IUCN Bangladesh Country Office Copyright: © 2015 Bangladesh Forest Department and IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holders, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holders. Citation: Of this volume IUCN Bangladesh. 2015. Red List of Bangladesh Volume 1: Summary. IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office, Dhaka, Bangladesh, pp. xvi+122. ISBN: 978-984-34-0733-7 Publication Assistant: Sheikh Asaduzzaman Design and Printed by: Progressive Printers Pvt. -

White-Rumped Sandpiper Pectoral Sandpiper Curlew Sandpiper

White-rumped Sandpiper Vagrant Calidris fuscicollis Native Range: America GB max: 1 Sep NI max: 0 A White-rumped Sandpiper was recorded This species has now been recorded by at Lunda Wick on Shetland in September. WeBS in seven of the last ten autumns. Pectoral Sandpiper Vagrant Calidris melanotos Native Range: America, N Siberia, Australia GB max: 5 Sep NI max: 0 Pectoral Sandpipers were recorded at Reservoir, Castle Lake, Clifford Hill Gravel seven sites in England and two in Scotland, Pits and Cliffe Pools. October records typically all in autumn. After one at comprised singles at Pagham Harbour and Boddam in August, birds were seen in Shapwick Heath NNR, and two together at September at Pulborough Brooks, Balgray Port Meadow in Oxfordshire. Curlew Sandpiper International threshold: 10,000 Calidris ferruginea Great Britain threshold: ? † † All-Ireland threshold: ? GB max: 201 Sep NI max: 5 Oct Curlew Sandpipers are passage migrants to the UK, breeding in central Siberia with the bulk wintering in central and southern Africa. They are scarce here in spring, and numbers in autumn are largely dependent on the summer’s breeding productivity. Autumn passage spanned July to October, with the majority in September when a respectable total of 202 was noted and five sites recorded double-figure counts, the peak of which was a total of 24 across four locations on the North Norfolk Curlew Sandpiper (Tommy Holden) Coast. For inland WeBS counters this species Single wintering birds were noted at represents an exciting find, and five at Farlington Marshes and Thanet Coast prior Nosterfield Gravel Pits and two at Upton to the change of calendar year, and at Warren NR were notable, representing the Thames Estuary in January and February. -

Birds of Ohio Shores

Birds of Ohio Shores: Diversity, Ecology and Management of Shorebirds in Ohio Woodlands Stewards Friday Morning Webinar, October 2, 2020 From Plovers to Pipers (who dey): A diversity tour of Ohio Shorebirds 2 Large Plovers: 3 Common Plovers: 4 Uncommon Plovers: 5 Avocet and Black-Necked Stilt 6 Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs 7 Solitary and Spotted Sandpipers 8 Willet and Upland Sandpiper 9 Whimbrel 10 Hudsonian and Marbled Godwits 11 Ruddy Turnstone and Sanderling 12 “Peeps” (= Calidris spp.) Hard to identify; they all look alike and often occur in large flocks. 13 Dublin and Pectoral Sandpiper 14 White-rumped and Baird’s Sandpipers 15 Semi-palmated and Least Sandpipers 16 Stilt and Buff-breasted Sandpipers 17 End of the “peeps” 18 Long and Short-billed Dowitcher 19 American Woodcock and Wilson’s Snipe 20 Wilson’s and Red-necked Phalaropes 21 And if that were not enough! 22 Breeding, juvenile, fall and spring plumages! 23 Prebalternate and prebasic molts (all spp. of shorebirds, not limited to peeps) Feathers wear so plumage changes spring to fall. 24 Shorebird Guilds Body Size Leg Length Bill size and shape Foraging behavior Habitat type (wetland zone) 25 Shorebird Guilds Small gleaners (beach, dry mudflat) Small probers (moist mudflat) Large probers (moist mudflat, shallow water) Large gleaners (shallow water) 26 Shorebird Habitats Meadow/Marsh Deep (er) Water Shallow Water Wet Mudflat Dry Mudflat 27 28 Shorebird Habitats Dry mudflat species: Killdeer Baird’s Sandpiper Buff-breasted Sandpiper Black-bellied Plover Golden Plover 29 -

The Status and Occurrence of Curlew Sandpiper (Calidris Ferruginea) in British Columbia

The Status and Occurrence of Curlew Sandpiper (Calidris ferruginea) in British Columbia. By Rick Toochin. Introduction and Distribution The Curlew Sandpiper (Calidris ferruginea) is an elegant species of shorebird that breeds from Taymyr Peninsula in the central Russian Arctic, east along the shorelines of the Arctic Ocean to the coastline of the Chukotka Peninsula in the Russian Far East and has bred in Alaska at Barrow, Oliktok Point and Deadhorse (Hayman et al. 1986, Paulson 2005, O’Brien et al. 2006, West 2008, Brazil 2009). This species is highly migratory with the entire breeding population moving south over a large area of both Europe and Asia to spend the winter from Sub-Sahara Africa, east through coastal regions of India, into Bangladesh, Burma, throughout Southeast Asia and south into Australia and New Zealand (Hayman et al. 1986, Paulson 2005, O’Brien et al. 2006, Brazil 2009). Small groups of birds are also known to winter in Israel, Iraq and occasionally in Western Europe (O’Brien et al. 2006). In North America, the Curlew Sandpiper is a regular vagrant along the Atlantic coast with scattered records for the interior states and Provinces (O’Brien et al. 2006). Along the west coast, the Curlew Sandpiper is a rare species in Alaska where it is considered a casual migrant in the Aleutian Islands and Bering Sea regions as well as the northern regions of the state (West 2008). The Curlew Sandpiper is ever rare in the southeastern regions of the state and is considered accidental in the southern Panhandle region of Alaska (West 2008.) South of Alaska, the Curlew Sandpiper is a rare bird with California having only thirty-three accepted records (Hamilton et al. -

Birdsrussia Report on Shorebird Hunting 2019

BirdsRussia Kamchatka Branch of Pacific Institute of Geography of Far-eastern Branch of Russian Academy of Science Working Group on Shorebirds of Northern Eurasia Report for the EAAFP, Australian Government and CMS ***** The first approach to assessment of hunting pressure on shorebirds in selected areas of the Kamchatka Peninsula, with special focus on the Far-Eastern Curlew Moscow – Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky 2019 Prepared by Konstantin B. Klokov, Saint-Petersburg State University, [email protected] Yuri N. Gerasimov, Kamchatka Branch of Pacific Institute of Geography FED RAS/BirdsRussia Kamchatka Branch, [email protected], Evgeny E. Syroechkovskiy Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment of Russian Federation /Birds Russia, Russia. [email protected] With contribution from: Sergey Kharitonov, Russian Bird Ringing Centre IPEE RAN Rus Acad Sci. Anton Ivanov, Working Group on Shorebirds on Northern Eurasia Dmitriy Dorofeev, All-Russian Research Institute for Nature Conservation Photos by authors of the report as well as local residents – hunters, whose names we promise not to mention for the reasons of confidentiality. 2 Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Project goal and objectives ................................................................................................................... 5 Materials and methods ........................................................................................................................ -

TheWoodcock

The Woodcock ANTIOCH BIRD CLUB Founded 2016 Volume 1 Number 2 November 2017 Welcome Part 2 Welcome to the second issue of The Woodcock! In this latest edition, the Antioch Bird Club reviews our October events, discusses new resources on campus, introduces our upcoming events for November, and shares recent bird highlights from Antioch’s campus. ABC Monthly Update Bagels and Birds On Saturday, October 14th, ABC held our 2nd Annual ‘Bagels and Birds’ event. From 8 AM until 12 PM, a total of 15 participants stopped by the library to help themselves to some fresh coffee and bagels while watching birds at the ABC feeders across from the library windows. The primary focus of the event was to introduce participants new to the club to its resources while spending a relaxing morning of birding from the comfort of the library’s soft furniture. In total, 18 species were observed, including Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Palm Warbler, and Dark-eyed Junco (the first of the fall season). For the full list of species -

The Calidris Sandpipers Part 2 by Jon L. Dunn

Los Angeles Birders Presents - Seven Deadly Stints and their Friends: The Calidris Sandpipers Part 2 by Jon L. Dunn – Los Angeles Birders (LAB) is a newly formed non-profit organization with the mission to bring birding, knowledge, and field experience together to encourage, educate, and empower birders. – We are an all-volunteer organization that aims to improve birders' field skills, enhance their understanding of avian biology and to introduce them the latest cutting-edge science and research. – Although our geographic focus is on the greater Los Angeles area, we welcome all birders who share the same passion, regardless of where they may live. – LEARN MORE ABOUT US AT: www.LosAngelesBirders.org – PLEASE TYPE YOUR QUESTIONS INTO THE Q&A, THEY WILL BE ANSWERED AT THE END OF THE WEBINAR. PHOTO BY JO HEINDEL Seven Deadly Stints and their Friends An Introduction to Calidris Sandpipers – Part 2 Jon L. Dunn Larry Sansone photos 20 October 2020 Los Angeles Birders Dunlin Calidris alpina (Linnaeus) 1758 (in Lapponia = Lapland = arctic regions of northern Norway, northern Sweden, northern Finland, and the Kola Peninsula in northwestern Russia in Europe) – Breeds in Holarctic. Ten recognized subspecies, divided into two groups, a smaller mainly European group that breeds from Greenland east to Taimyir, Siberia, Russia (three subspecies) and a larger northern Asian group from Lena River east and North America (seven subspecies). – Winters primarily (mainly coastal regions and north of Equator) from West, Gulf and East Coasts, British Isles and south to West Africa, and east to Arabian Peninsula, Persian Gulf, coastal China and southern Japan. – Common migrant along Pacific Coast and central Great Plains east; rare in eastern Great Basin to western Great Plains, reflecting partly the gap in breeding ranges between pacifica and arcticola with eastern North American hudsonia. -

Ruddy Turnstone Arenaria Interpres

Ruddy Turnstone Arenaria interpres Where this Bird Can Be Found N About this Bird ATLANTIC OCEAN The Ruddy Turnstone is a chunky shorebird with a reddish-brown back, black bib, orange legs and small pointed bill. It is an amazing long distance migrant capable of covering thousands of miles in a few days on migration. It breeds in the Arctic and winters as far south as Argentina. In the Caribbean it is observed mainly from August to May on our beaches and mudflats. The name ‘Turnstone’ comes from the way it CARIBBEAN SEA flips over small stones and shells in search of invertebrate food items in the sand. Bird Size 24 cm, 9.5 in. Color by number! Use the key below to color in the shorebird 1 = Yellow 2 = Orange 3 = Red 4 = White 5 = Brown 6 = Black 7 = Green 8 = Purple 9 = Dark blue 10 = Light blue Illustrated by: Kim McNett Birding Safari! Draw a picture for each item below 1. Something manmade 2. Two birds 3. Three shades of green (what items) 4. Something smelly (Good or bad) 5. A flowering plant 6. An animal that is not a bird 7. A sign of Spring 8. Something rough feeling 9. Two brown objects 10. A sound heard This is your bleed line. Life Cycle of a Bird Birds are warm blooded animals. They have feathers and wings, and they can walk on two legs. Birds lay eggs with hard shells. They have ear holes instead of ears, and they have a beak instead of a mouth with teeth.