Species Included in This Publication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amaranthus Pumilus (Seabeach Amaranth)

Bartonia No. 61, 2002-News and Notes Amaranthus pumilus Raf. (Seabeach Amaranth, Amaranthaceae) Rediscovered in Sussex County, Delaware In August of 2000, Amaranthus pumilus was rediscovered in Sussex Co., Delaware after 125 years without a sighting. It was first collected in Delaware in 1875 by Albert Commons (10 September 1875, A. Commons, s.n., "seabeach, Baltimore Hundred, Delaware," PH). Amaranthus pumilus was federally listed as threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1993. Historically, this species was known from Massachusetts south to South Carolina (Weakley et al. 1996). Amaranthus pumilus was reported as rediscovered at Assateague Island National Seashore, Worcester County, Maryland in 1998 (Ramsey 2000). Prior to rediscovery on Assateague Island and in Sussex County, A. pumilus was extant on Long Island, New York, and in North Carolina and South Carolina. Lisa Marie Kendall of the Delaware Natural Heritage Program, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Delaware Department of Natural Resources discovered the first plants on 7 August 2000. Subsequent surveys revealed a total of 41 individuals scattered over 22 kilometers of Atlantic shoreline. All plants found are within the boundaries of Delaware Seashore and Fenwick Island State Parks. The largest number of plants (28) was found within a 1.5-km stretch of shoreline near the swimming beach at Delaware Seashore State Park. This section of beach is the only area where A. pumilus was found that is off-limits to vehicular traffic. This area provides the best habitat for the long-term survival of A. pumilus. Individual plants were found growing on relatively open sand near the base of the primary foredune. -

Lonicera Spp

Species: Lonicera spp. http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/lonspp/all.html SPECIES: Lonicera spp. Choose from the following categories of information. Introductory Distribution and occurrence Botanical and ecological characteristics Fire ecology Fire effects Fire case studies Management considerations References INTRODUCTORY SPECIES: Lonicera spp. AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION FEIS ABBREVIATION SYNONYMS NRCS PLANT CODE COMMON NAMES TAXONOMY LIFE FORM FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS OTHER STATUS AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: Munger, Gregory T. 2005. Lonicera spp. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2007, September 24]. FEIS ABBREVIATIONS: LONSPP LONFRA LONMAA LONMOR LONTAT LONXYL LONBEL SYNONYMS: None NRCS PLANT CODES [172]: LOFR LOMA6 LOMO2 LOTA LOXY 1 of 67 9/24/2007 4:44 PM Species: Lonicera spp. http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/lonspp/all.html LOBE COMMON NAMES: winter honeysuckle Amur honeysuckle Morrow's honeysuckle Tatarian honeysuckle European fly honeysuckle Bell's honeysuckle TAXONOMY: The currently accepted genus name for honeysuckle is Lonicera L. (Caprifoliaceae) [18,36,54,59,82,83,93,133,161,189,190,191,197]. This report summarizes information on 5 species and 1 hybrid of Lonicera: Lonicera fragrantissima Lindl. & Paxt. [36,82,83,133,191] winter honeysuckle Lonicera maackii Maxim. [18,27,36,54,59,82,83,131,137,186] Amur honeysuckle Lonicera morrowii A. Gray [18,39,54,60,83,161,186,189,190,197] Morrow's honeysuckle Lonicera tatarica L. [18,38,39,54,59,60,82,83,92,93,157,161,186,190,191] Tatarian honeysuckle Lonicera xylosteum L. -

Weed Risk Assessment for Vitex Rotundifolia L. F. (Lamiaceae)

Weed Risk Assessment for Vitex United States rotundifolia L. f. (Lamiaceae) – Beach Department of Agriculture vitex Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service June 4, 2013 Version 2 Left: Infestation in South Carolina growing down to water line and with runners and fruit stripped by major winter storm (Randy Westbrooks, U.S. Geological Survey, Bugwood.org). Right: A runner with flowering shoots (Forest and Kim Starr, Starr Environmental, Bugwood.org). Agency Contact: Plant Epidemiology and Risk Analysis Laboratory Center for Plant Health Science and Technology Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service United States Department of Agriculture 1730 Varsity Drive, Suite 300 Raleigh, NC 27606 Weed Risk Assessment for Vitex rotundifolia Introduction Plant Protection and Quarantine (PPQ) regulates noxious weeds under the authority of the Plant Protection Act (7 U.S.C. § 7701-7786, 2000) and the Federal Seed Act (7 U.S.C. § 1581-1610, 1939). A noxious weed is defined as “any plant or plant product that can directly or indirectly injure or cause damage to crops (including nursery stock or plant products), livestock, poultry, or other interests of agriculture, irrigation, navigation, the natural resources of the United States, the public health, or the environment” (7 U.S.C. § 7701-7786, 2000). We use weed risk assessment (WRA)—specifically, the PPQ WRA model (Koop et al., 2012)—to evaluate the risk potential of plants, including those newly detected in the United States, those proposed for import, and those emerging as weeds elsewhere in the world. Because the PPQ WRA model is geographically and climatically neutral, it can be used to evaluate the baseline invasive/weed potential of any plant species for the entire United States or for any area within it. -

Plastid Phylogenomic Insights Into the Evolution of the Caprifoliaceae S.L. (Dipsacales)

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 142 (2020) 106641 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Plastid phylogenomic insights into the evolution of the Caprifoliaceae s.l. T (Dipsacales) Hong-Xin Wanga,1, Huan Liub,c,1, Michael J. Moored, Sven Landreine, Bing Liuf,g, Zhi-Xin Zhua, ⁎ Hua-Feng Wanga, a Key Laboratory of Tropical Biological Resources of Ministry of Education, School of Life and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Hainan University, Haikou 570228, China b BGI-Shenzhen, Beishan Industrial Zone, Yantian District, Shenzhen 518083, China c State Key Laboratory of Agricultural Genomics, BGI-Shenzhen, Shenzhen 518083, China d Department of Biology, Oberlin College, Oberlin, OH 44074, USA e Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun, 666303, China f State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Science, Beijing 100093, China g Sino-African Joint Research Centre, Chinese Academy of Science, Wuhan 430074, China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The family Caprifoliaceae s.l. is an asterid angiosperm clade of ca. 960 species, most of which are distributed in Caprifoliaceae s.l. temperate regions of the northern hemisphere. Recent studies show that the family comprises seven major Dipsacales clades: Linnaeoideae, Zabelia, Morinoideae, Dipsacoideae, Valerianoideae, Caprifolioideae, and Diervilloideae. Plastome However, its phylogeny at the subfamily or genus level remains controversial, and the backbone relationships Phylogenetics among subfamilies are incompletely resolved. In this study, we utilized complete plastome sequencing to resolve the relationships among the subfamilies of the Caprifoliaceae s.l. and clarify several long-standing controversies. We generated and analyzed plastomes of 48 accessions of Caprifoliaceae s.l., representing 44 species, six sub- families and one genus. -

Akebia Quinata

Akebia quinata Akebia quinata Chocolate vine, five- leaf Akebia Introduction Native to eastern Asia, the genus Akebia consists of five species, with four species and three subspecies reported in China[168]. Members of this genus are deciduous or semi-deciduous twining vines. The roots, vines, and fruits can be used for medicinal purposes. The sweet fruits can be used in wine-making[4]. Taxonomy: Akebia quinata leaves. (Photo by Shep Zedaker, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State FAM ILY: Lardizabalaceae University.) Genus: Akebia Decne. clustered on the branchlets, and divided male and the rest are female. Appearing Species of Akebia in China into five, or sometimes three to four from June to August, oblong or elliptic purplish fruits split open when mature, revealing dark, brownish, flat seeds Scientific Name Scientific Name arranged irregularly in rows[4]. A. chingshuiensis T. Shimizu A. quinata (Houtt.) Decne A. longeracemosa Matsumura A. trifoliata (Thunb.) Koidz Habitat and Distribution A. quinata grows near forest margins Description or six to seven papery leaflets that are along streams, as scrub on mountain Akebia quinata is a deciduous woody obovate or obovately elliptic, 2-5 cm slopes at 300 - 1500 m elevation, in vine with slender, twisting, cylindrical long, 1.5-2.5 cm wide, with a round or most of the provinces through which [4] stems bearing small, round lenticels emarginate apex and a round or broadly the Yellow River flows . It has a native on the grayish brown surface. Bud cuneate base. Infrequently blooming, range in Anhui, Fujian, Henan, Hubei, scales are light reddish-brown with the inflorescence is an axillary raceme Hunan, Jiangsu, Jiangxi, Shandong, an imbricate arrangement. -

Vitex Rotundifolia L.F

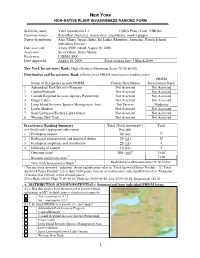

NEW YORK NON -NATIVE PLANT INVASIVENESS RANKING FORM Scientific name: Vitex rotundifolia L.f. USDA Plants Code: VIRO80 Common names: Roundleaf chastetree, beach vitex, chasteberry, monk's pepper Native distribution: Asia (China, Japan), India, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Australia, Pacific Islands (inlcuding Hawaii) Date assessed: 3 June 2009; edited August 19, 2009 Assessors: Steve Glenn, Gerry Moore Reviewers: LIISMA SRC Date Approved: August 19, 2009 Form version date: 3 March 2009 New York Invasiveness Rank: High (Relative Maximum Score 70.00-80.00) Distribution and Invasiveness Rank ( Obtain from PRISM invasiveness ranking form ) PRISM Status of this species in each PRISM: Current Distribution Invasiveness Rank 1 Adirondack Park Invasive Program Not Assessed Not Assessed 2 Capital/Mohawk Not Assessed Not Assessed 3 Catskill Regional Invasive Species Partnership Not Assessed Not Assessed 4 Finger Lakes Not Assessed Not Assessed 5 Long Island Invasive Species Management Area Not Present Moderate 6 Lower Hudson Not Assessed Not Assessed 7 Saint Lawrence/Eastern Lake Ontario Not Assessed Not Assessed 8 Western New York Not Assessed Not Assessed Invasiveness Ranking Summary Total (Total Answered*) Total (see details under appropriate sub-section) Possible 1 Ecological impact 40 ( 40 ) 37 2 Biological characteristic and dispersal ability 25 ( 25 ) 20 3 Ecological amplitude and distribution 25 ( 25 ) 4 4 Difficulty of control 10 ( 10 ) 8 Outcome score 100 ( 100 )b 73.00 a † Relative maximum score 73.00 § New York Invasiveness Rank High (Relative Maximum Score 70.00-80.00) * For questions answered “unknown” do not include point value in “Total Answered Points Possible.” If “Total Answered Points Possible” is less than 70.00 points, then the overall invasive rank should be listed as “Unknown.” †Calculated as 100(a/b) to two decimal places. -

PRE Evaluation Report for Lonicera Fragrantissima

PRE Evaluation Report -- Lonicera fragrantissima Plant Risk Evaluator -- PRE™ Evaluation Report Lonicera fragrantissima -- Georgia 2017 Farm Bill PRE Project PRE Score: 15 -- Evaluate this plant further Confidence: 65 / 100 Questions answered: 19 of 20 -- Valid (80% or more questions answered) Privacy: Public Status: Submitted Evaluation Date: November 13, 2017 This PDF was created on August 13, 2018 Page 1/18 PRE Evaluation Report -- Lonicera fragrantissima Plant Evaluated Lonicera fragrantissima Image by Kurt Stüber Page 2/18 PRE Evaluation Report -- Lonicera fragrantissima Evaluation Overview A PRE™ screener conducted a literature review for this plant (Lonicera fragrantissima) in an effort to understand the invasive history, reproductive strategies, and the impact, if any, on the region's native plants and animals. This research reflects the data available at the time this evaluation was conducted. Summary Sweet breath of spring (Lonicera fragrantissima) is a deciduous shrub that grows up to 6-10' tall and wide. It bears many small, white, and very fragrant flowers in the early spring, followed by small red berries that grow in early to mid summer. L. fragrantissima is naturalized across much of the Eastern U.S. and is listed on the Georgia and South Carolina EPPC sites as well as by the Tennessee Invasive Plant Council. General Information Status: Submitted Screener: Lila Uzzell Evaluation Date: November 13, 2017 Plant Information Plant: Lonicera fragrantissima Regional Information Region Name: Georgia Climate Matching Map To answer four of the PRE questions for a regional evaluation, a climate map with three climate data layers (Precipitation, UN EcoZones, and Plant Hardiness) is needed. These maps were built using a toolkit created in collaboration with GreenInfo Network, USDA, PlantRight, California-Invasive Plant Council, and The Information Center for the Environment at UC Davis. -

Botanical Name Common Name

Approved Approved & as a eligible to Not eligible to Approved as Frontage fulfill other fulfill other Type of plant a Street Tree Tree standards standards Heritage Tree Tree Heritage Species Botanical Name Common name Native Abelia x grandiflora Glossy Abelia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes White Forsytha; Korean Abeliophyllum distichum Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Abelialeaf Acanthropanax Fiveleaf Aralia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes sieboldianus Acer ginnala Amur Maple Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Aesculus parviflora Bottlebrush Buckeye Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Aesculus pavia Red Buckeye Shrub, Deciduous No No Yes Yes Alnus incana ssp. rugosa Speckled Alder Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Alnus serrulata Hazel Alder Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Amelanchier humilis Low Serviceberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Amelanchier stolonifera Running Serviceberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes False Indigo Bush; Amorpha fruticosa Desert False Indigo; Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No No Not eligible Bastard Indigo Aronia arbutifolia Red Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Aronia melanocarpa Black Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Aronia prunifolia Purple Chokeberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Groundsel-Bush; Eastern Baccharis halimifolia Shrub, Deciduous No No Yes Yes Baccharis Summer Cypress; Bassia scoparia Shrub, Deciduous No No No Yes Burning-Bush Berberis canadensis American Barberry Shrub, Deciduous Yes No No Yes Common Barberry; Berberis vulgaris Shrub, Deciduous No No No No Not eligible European Barberry Betula pumila -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY BIBLIOGRAPHY Ackerfield, J., and J. Wen. 2002. A morphometric analysis of Hedera L. (the ivy genus, Araliaceae) and its taxonomic implications. Adansonia 24: 197-212. Adams, P. 1961. Observations on the Sagittaria subulata complex. Rhodora 63: 247-265. Adams, R.M. II, and W.J. Dress. 1982. Nodding Lilium species of eastern North America (Liliaceae). Baileya 21: 165-188. Adams, R.P. 1986. Geographic variation in Juniperus silicicola and J. virginiana of the Southeastern United States: multivariant analyses of morphology and terpenoids. Taxon 35: 31-75. ------. 1995. Revisionary study of Caribbean species of Juniperus (Cupressaceae). Phytologia 78: 134-150. ------, and T. Demeke. 1993. Systematic relationships in Juniperus based on random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs). Taxon 42: 553-571. Adams, W.P. 1957. A revision of the genus Ascyrum (Hypericaceae). Rhodora 59: 73-95. ------. 1962. Studies in the Guttiferae. I. A synopsis of Hypericum section Myriandra. Contr. Gray Herbarium Harv. 182: 1-51. ------, and N.K.B. Robson. 1961. A re-evaluation of the generic status of Ascyrum and Crookea (Guttiferae). Rhodora 63: 10-16. Adams, W.P. 1973. Clusiaceae of the southeastern United States. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 89: 62-71. Adler, L. 1999. Polygonum perfoliatum (mile-a-minute weed). Chinquapin 7: 4. Aedo, C., J.J. Aldasoro, and C. Navarro. 1998. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sections Batrachioidea and Divaricata (Geraniaceae). Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 85: 594-630. Affolter, J.M. 1985. A monograph of the genus Lilaeopsis (Umbelliferae). Systematic Bot. Monographs 6. Ahles, H.E., and A.E. -

SHRUBS & HEDGING ETC Abelia Grandiflora Evergreen Easy to Grow in Most Soil Conditions. Glossy Green Leaves with White Flowe

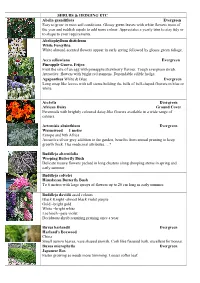

SHRUBS & HEDGING ETC Abelia grandiflora Evergreen Easy to grow in most soil conditions. Glossy green leaves with white flowers most of the year and reddish sepals to add more colour. Appreciates a yearly trim to stay tidy or to shape to your requirements. Abeliophyllum distichum White Forsythia White almond-scented flowers appear in early spring followed by glossy green foliage. Acca sellowiana Evergreen Pineapple Guava, Feijoa Fruit the size of an egg with pineapple/strawberry flavour. Tough evergreen shrub. Attractive flowers with bright red stamens. Dependable edible hedge. Agapanthus White & Blue Evergreen Long strap like leaves with tall stems holding the balls of bell-shaped flowers in blue or white. Arctotis Evergreen African Daisy Ground Cover Perennials with brightly coloured daisy-like flowers available in a wide range of colours. Artemisia absinthium Evergreen Wormwood 1 metre Europe and Nth Africa Attractive silver grey addition to the garden, benefits from annual pruning to keep growth thick. Has medicinal attributes….? Buddleja alternifolia Weeping Butterfly Bush Delicate mauve flowers packed in long clusters along drooping stems in spring and early summer. Buddleja colvelei Himalayan Butterfly Bush To 6 metres with large sprays of flowers up to 20 cm long in early summer. Buddleja davidii asstd colours Black Knight -almost black violet purple Gold –bright gold White –bright white Lochinch –pale violet Deciduous shrub requiring pruning once a year. Buxus harlandii Evergreen Harland’s Boxwood China Small narrow leaves, vase shaped growth. Cork like fissured bark, excellent for bonsai. Buxus microphylla Evergreen Japanese Box Faster growing so needs more trimming. Looser softer leaf. Buxus sempivirens Evergreen English Box Traditional small to medium hedging plant. -

Minnesota's Top 124 Terrestrial Invasive Plants and Pests

Photo by RichardhdWebbWebb 0LQQHVRWD V7RS 7HUUHVWULDO,QYDVLYH 3ODQWVDQG3HVWV 3ULRULWLHVIRU5HVHDUFK Sciencebased solutions to protect Minnesota’s prairies, forests, wetlands, and agricultural resources Contents I. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 II. Prioritization Panel members ....................................................................................................... 4 III. Seventeen criteria, and their relative importance, to assess the threat a terrestrial invasive species poses to Minnesota ...................................................................................................................... 5 IV. Prioritized list of terrestrial invasive insects ................................................................................. 6 V. Prioritized list of terrestrial invasive plant pathogens .................................................................. 7 VI. Prioritized list of plants (weeds) ................................................................................................... 8 VII. Terrestrial invasive insects (alphabetically by common name): criteria ratings to determine threat to Minnesota. .................................................................................................................................... 9 VIII. Terrestrial invasive pathogens (alphabetically by disease among bacteria, fungi, nematodes, oomycetes, parasitic plants, and viruses): criteria ratings -

An Uninhabited, Undeveloped Barrier Island. (Under the Direction of Thomas R

ABSTRACT ROSENFELD, KRISTEN MARIE. Ecology of Bird Island, North Carolina: an uninhabited, undeveloped barrier island. (Under the direction of Thomas R. Wentworth.) Barrier islands include some of the most endangered and fragmented ecosystems on the Atlantic coast, providing critical habitat for many species, including some that are threatened and endangered. As the vast majority of these islands have been developed for human usage study and protection of the few remaining undeveloped and undisturbed islands is critical. This study was undertaken in order to characterize the vascular plant communities on Bird Island, an uninhabited, undeveloped barrier island on the border of North and South Carolina, with the objectives of a thorough survey of flora, vegetation, and environment, classification of plant communities, and multivariate analysis of vegetation and environmental data. A floristic inventory of the island and its associated marshes was conducted during the growing season (May- November) of 2002 and 2003. One hundred four 100m2 plots were inventoried for vegetation and environment using protocols developed by the Carolina Vegetation Survey. Plant communities were identified according to the National Vegetation Classification, the Classification of the Natural Communities of North Carolina, and the Carolina Vegetation Survey. Interpretation of vegetation patterns was based on multivariate analysis of vegetation and environmental data. Ninety-one vascular plant species in 35 families, including 4 exotic species, were distributed across 12 communities. Communities on Bird Island appear to be distinctive when compared to those described for other barrier islands in the region. Additionally, the vegetation survey on Bird Island revealed suitable habitat for the federally listed Seabeach amaranth (Amaranthus pumilus); an important dune-building annual of the North American Atlantic coast.