Dune Ecology: Beaches and Primary Dunes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Quick Guide to Southeast Florida's Coral Reefs

A Quick Guide to Southeast Florida’s Coral Reefs DAVID GILLIAM NATIONAL CORAL REEF INSTITUTE NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY Spring 2013 Prepared by the Land-based Sources of Pollution Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) of the Southeast Florida Coral Reef Initiative (SEFCRI) BRIAN WALKER NATIONAL CORAL REEF INSTITUTE, NOVA SOUTHEASTERN Southeast Florida’s coral-rich communities are more valuable than UNIVERSITY the Spanish treasures that sank nearby. Like the lost treasures, these amazing reefs lie just a few hundred yards off the shores of Martin, Palm Beach, Broward and Miami-Dade Counties where more than one-third of Florida’s 19 million residents live. Fishing, diving, and boating help attract millions of visitors to southeast Florida each year (30 million in 2008/2009). Reef-related expen- ditures generate $5.7 billion annually in income and sales, and support more than 61,000 local jobs. Such immense recreational activity, coupled with the pressures of coastal development, inland agriculture, and robust cruise and commercial shipping industries, threaten the very survival of our reefs. With your help, reefs will be protected from local stresses and future generations will be able to enjoy their beauty and economic benefits. Coral reefs are highly diverse and productive, yet surprisingly fragile, ecosystems. They are built by living creatures that require clean, clear seawater to settle, mature and reproduce. Reefs provide safe havens for spectacular forms of marine life. Unfortunately, reefs are vulnerable to impacts on scales ranging from local and regional to global. Global threats to reefs have increased along with expanding ART SEITZ human populations and industrialization. Now, warming seawater temperatures and changing ocean chemistry from carbon dioxide emitted by the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation are also starting to imperil corals. -

Amaranthus Pumilus (Seabeach Amaranth)

Bartonia No. 61, 2002-News and Notes Amaranthus pumilus Raf. (Seabeach Amaranth, Amaranthaceae) Rediscovered in Sussex County, Delaware In August of 2000, Amaranthus pumilus was rediscovered in Sussex Co., Delaware after 125 years without a sighting. It was first collected in Delaware in 1875 by Albert Commons (10 September 1875, A. Commons, s.n., "seabeach, Baltimore Hundred, Delaware," PH). Amaranthus pumilus was federally listed as threatened by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1993. Historically, this species was known from Massachusetts south to South Carolina (Weakley et al. 1996). Amaranthus pumilus was reported as rediscovered at Assateague Island National Seashore, Worcester County, Maryland in 1998 (Ramsey 2000). Prior to rediscovery on Assateague Island and in Sussex County, A. pumilus was extant on Long Island, New York, and in North Carolina and South Carolina. Lisa Marie Kendall of the Delaware Natural Heritage Program, Division of Fish and Wildlife, Delaware Department of Natural Resources discovered the first plants on 7 August 2000. Subsequent surveys revealed a total of 41 individuals scattered over 22 kilometers of Atlantic shoreline. All plants found are within the boundaries of Delaware Seashore and Fenwick Island State Parks. The largest number of plants (28) was found within a 1.5-km stretch of shoreline near the swimming beach at Delaware Seashore State Park. This section of beach is the only area where A. pumilus was found that is off-limits to vehicular traffic. This area provides the best habitat for the long-term survival of A. pumilus. Individual plants were found growing on relatively open sand near the base of the primary foredune. -

Brighton Beach Groynes

CASE STUDY: BRIGHTON BEACH GROYNES BRIGHTON, SOUTH AUSTRALIA FEBRUARY 2017 CLIENT: CITY OF HOLDFAST BAY Adelaide’s beaches are affected by a common phenomenon called ELCOROCK® longshore drift - the flow of water, in one direction, along a beach occurring as a result of winds and currents. In Adelaide longshore drift flows from south to north and it frequently erodes beaches The ELCOROCK system consists of sand- over time, particularly during storm events when tides are high and filled geotextile containers built to form sea is rough. a stabilising, defensive barrier against coastal erosion. Without sand replenishment, the southern end of Adelaide’s beaches will slowly erode and undermine existing infrastructure at The robustness and stability of Elcorock the sea/land interface. The objective of Elcorock sand container geotextile containers provide a solutions groynes, laid perpendicular to the beach, is to capture some of for other marine structures such as groynes and breakwaters. These the natural sand as well as dredged sand, that moves along the structures extend out into the wave zone coast. Over time, this process builds up the beach, particularly and provide marina and beach protection, between the groynes which results in the protection of the existing sand movement control and river training. infrastructure. The size of the container can easily be Geofabrics met with the city of Holdfast Bay in the early stages of selected based on the wave climate and the project to discuss the product, durability and previous projects other conditions ensuring stability under with a similar application. Due to recent weather events, the beach the most extreme conditions. -

CITY of MIAMI BEACH DUNE MANAGEMENT PLAN January 2016

CITY OF MIAMI BEACH DUNE MANAGEMENT PLAN January 2016 Prepared by: CITY OF MIAMI BEACH COASTAL MANAGEMENT 1700 Convention Center Drive AND CONSULTING Miami Beach, Florida 33139 7611 Lawrence Road Boynton Beach, Florida 33436 I. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Coastal dunes are habitat for wildlife and support a high biodiversity of flora and fauna. They also keep beaches healthy by accreting sand and minimizing beach erosion rates. The dunes protect coastal infrastructure and upland properties from storm damage by blocking storm surge and absorbing wave energy. Therefore, a healthy dune system is an invaluable asset to coastal communities like Miami Beach. The purpose of the City of Miami Beach Dune Management Plan (“the Plan”) is to outline the framework and specifications that the City will use to foster and maintain a healthy, stable, and natural dune system that is appropriate for its location and reduces public safety and maintenance concerns. The Plan shall guide the City’s efforts in managing the urban, man-made dune as close to a natural system as possible and ensuring the dune provides storm protection, erosion control, and a biologically-rich habitat for local species. II. OBJECTIVES This plan was developed collaboratively with local government and community stakeholders, as well as local experts to meet the following primary objectives: 1. Reduce to the maximum extent possible the presence of invasive, non-native pest plant species within the dune system. Non-native species compete with and overwhelm more stable native dune plants, thereby threatening the stability and biodiversity of the dune system. Reducing the presence of aggressive, non-native vegetation preserves and promotes the structural integrity and biodiversity of the dune. -

Weed Risk Assessment for Vitex Rotundifolia L. F. (Lamiaceae)

Weed Risk Assessment for Vitex United States rotundifolia L. f. (Lamiaceae) – Beach Department of Agriculture vitex Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service June 4, 2013 Version 2 Left: Infestation in South Carolina growing down to water line and with runners and fruit stripped by major winter storm (Randy Westbrooks, U.S. Geological Survey, Bugwood.org). Right: A runner with flowering shoots (Forest and Kim Starr, Starr Environmental, Bugwood.org). Agency Contact: Plant Epidemiology and Risk Analysis Laboratory Center for Plant Health Science and Technology Plant Protection and Quarantine Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service United States Department of Agriculture 1730 Varsity Drive, Suite 300 Raleigh, NC 27606 Weed Risk Assessment for Vitex rotundifolia Introduction Plant Protection and Quarantine (PPQ) regulates noxious weeds under the authority of the Plant Protection Act (7 U.S.C. § 7701-7786, 2000) and the Federal Seed Act (7 U.S.C. § 1581-1610, 1939). A noxious weed is defined as “any plant or plant product that can directly or indirectly injure or cause damage to crops (including nursery stock or plant products), livestock, poultry, or other interests of agriculture, irrigation, navigation, the natural resources of the United States, the public health, or the environment” (7 U.S.C. § 7701-7786, 2000). We use weed risk assessment (WRA)—specifically, the PPQ WRA model (Koop et al., 2012)—to evaluate the risk potential of plants, including those newly detected in the United States, those proposed for import, and those emerging as weeds elsewhere in the world. Because the PPQ WRA model is geographically and climatically neutral, it can be used to evaluate the baseline invasive/weed potential of any plant species for the entire United States or for any area within it. -

Beach Nourishment: Massdep's Guide to Best Management Practices for Projects in Massachusetts

BBEACHEACH NNOURISHMEOURISHMENNTT MassDEP’sMassDEP’s GuideGuide toto BestBest ManagementManagement PracticesPractices forfor ProjectsProjects inin MassachusettsMassachusetts March 2007 acknowledgements LEAD AUTHORS: Rebecca Haney (Coastal Zone Management), Liz Kouloheras, (MassDEP), Vin Malkoski (Mass. Division of Marine Fisheries), Jim Mahala (MassDEP) and Yvonne Unger (MassDEP) CONTRIBUTORS: From MassDEP: Fred Civian, Jen D’Urso, Glenn Haas, Lealdon Langley, Hilary Schwarzenbach and Jim Sprague. From Coastal Zone Management: Bob Boeri, Mark Borrelli, David Janik, Julia Knisel and Wendolyn Quigley. Engineering consultants from Applied Coastal Research and Engineering Inc. also reviewed the document for technical accuracy. Lead Editor: David Noonan (MassDEP) Design and Layout: Sandra Rabb (MassDEP) Photography: Sandra Rabb (MassDEP) unless otherwise noted. Massachusetts Massachusetts Office Department of of Coastal Zone Environmental Protection Management 1 Winter Street 251 Causeway Street Boston, MA Boston, MA table of contents I. Glossary of Terms 1 II. Summary 3 II. Overview 6 • Purpose 6 • Beach Nourishment 6 • Specifications and Best Management Practices 7 • Permit Requirements and Timelines 8 III. Technical Attachments A. Beach Stability Determination 13 B. Receiving Beach Characterization 17 C. Source Material Characterization 21 D. Sample Problem: Beach and Borrow Site Sediment Analysis to Determine Stability of Nourishment Material for Shore Protection 22 E. Generic Beach Monitoring Plan 27 F. Sample Easement 29 G. References 31 GLOSSARY Accretion - the gradual addition of land by deposition of water-borne sediment. Beach Fill – also called “artificial nourishment”, “beach nourishment”, “replenishment”, and “restoration,” comprises the placement of sediment within the nearshore sediment transport system (see littoral zone). (paraphrased from Dean, 2002) Beach Profile – the cross-sectional shape of a beach plotted perpendicular to the shoreline. -

The Sarcophagidae (Diptera) Described by C

© Entomologica Fennica. 12.X.1993 The Sarcophagidae (Diptera) described by C. De Geer, J. H. S. Siebke, and 0. Ringdahl ThomasPape Pape, T. 1993: The Sarcophagidae (Diptera) described by C. De Geer, J. H. S. Siebke, and 0. Ringdahl.- Entomol. Fennica 4:143-150. All species-group taxa described by or assigned to C. De Geer, J.H.S. Siebke, and 0. Ringdahl are revised. Musca vivipara minor De Geer, 1776 and Musca vivipara major De Geer, 1776 are considered binary and outside nomenclature. The single species-group name ascribed to Siebke is shown to be unavailable. A lectotype of Sarcophaga vertic ina Ringdahl, 1945 [= S. pleskei (Rohdendorf, 1937)] is designated and Brachicoma borealis Ringdahl, 1932 is revised and resurrected as a distinct species. Thomas Pape, Zoological Museum, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100 Copen hagen, Denmark 1. Introduction specimens concerned or to the taxonomic deci sions made. Original labels of primary type All Sarcophagidae described by the Scandinavian specimens have been cited, with text from differ authors Fabricius, Fallen, and Zetterstedt were ent labels separated by semicolons. Alllectotypes treated by Pape (1986), and the single species de have been given a red label stating their status as scribed by Linnaeus was revised (for the first time!) such. Paralectotypes, if any, have been recovered by Richet (1987). Other Scandinavian authors of and are discussed separately under the entry 'ad taxa in this family include Charles (or Carl) De ditional material.' Geer and Oscar Ringdahl, who have each proposed two species-group names, and it is the purpose of 3. Results the present paper to revise these taxa and to comment on their identity and availability. -

Final Report 1

Sand pit for Biodiversity at Cep II quarry Researcher: Klára Řehounková Research group: Petr Bogusch, David Boukal, Milan Boukal, Lukáš Čížek, František Grycz, Petr Hesoun, Kamila Lencová, Anna Lepšová, Jan Máca, Pavel Marhoul, Klára Řehounková, Jiří Řehounek, Lenka Schmidtmayerová, Robert Tropek Březen – září 2012 Abstract We compared the effect of restoration status (technical reclamation, spontaneous succession, disturbed succession) on the communities of vascular plants and assemblages of arthropods in CEP II sand pit (T řebo ňsko region, SW part of the Czech Republic) to evaluate their biodiversity and conservation potential. We also studied the experimental restoration of psammophytic grasslands to compare the impact of two near-natural restoration methods (spontaneous and assisted succession) to establishment of target species. The sand pit comprises stages of 2 to 30 years since site abandonment with moisture gradient from wet to dry habitats. In all studied groups, i.e. vascular pants and arthropods, open spontaneously revegetated sites continuously disturbed by intensive recreation activities hosted the largest proportion of target and endangered species which occurred less in the more closed spontaneously revegetated sites and which were nearly absent in technically reclaimed sites. Out results provide clear evidence that the mosaics of spontaneously established forests habitats and open sand habitats are the most valuable stands from the conservation point of view. It has been documented that no expensive technical reclamations are needed to restore post-mining sites which can serve as secondary habitats for many endangered and declining species. The experimental restoration of rare and endangered plant communities seems to be efficient and promising method for a future large-scale restoration projects in abandoned sand pits. -

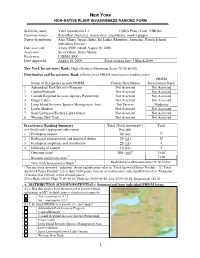

Vitex Rotundifolia L.F

NEW YORK NON -NATIVE PLANT INVASIVENESS RANKING FORM Scientific name: Vitex rotundifolia L.f. USDA Plants Code: VIRO80 Common names: Roundleaf chastetree, beach vitex, chasteberry, monk's pepper Native distribution: Asia (China, Japan), India, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Australia, Pacific Islands (inlcuding Hawaii) Date assessed: 3 June 2009; edited August 19, 2009 Assessors: Steve Glenn, Gerry Moore Reviewers: LIISMA SRC Date Approved: August 19, 2009 Form version date: 3 March 2009 New York Invasiveness Rank: High (Relative Maximum Score 70.00-80.00) Distribution and Invasiveness Rank ( Obtain from PRISM invasiveness ranking form ) PRISM Status of this species in each PRISM: Current Distribution Invasiveness Rank 1 Adirondack Park Invasive Program Not Assessed Not Assessed 2 Capital/Mohawk Not Assessed Not Assessed 3 Catskill Regional Invasive Species Partnership Not Assessed Not Assessed 4 Finger Lakes Not Assessed Not Assessed 5 Long Island Invasive Species Management Area Not Present Moderate 6 Lower Hudson Not Assessed Not Assessed 7 Saint Lawrence/Eastern Lake Ontario Not Assessed Not Assessed 8 Western New York Not Assessed Not Assessed Invasiveness Ranking Summary Total (Total Answered*) Total (see details under appropriate sub-section) Possible 1 Ecological impact 40 ( 40 ) 37 2 Biological characteristic and dispersal ability 25 ( 25 ) 20 3 Ecological amplitude and distribution 25 ( 25 ) 4 4 Difficulty of control 10 ( 10 ) 8 Outcome score 100 ( 100 )b 73.00 a † Relative maximum score 73.00 § New York Invasiveness Rank High (Relative Maximum Score 70.00-80.00) * For questions answered “unknown” do not include point value in “Total Answered Points Possible.” If “Total Answered Points Possible” is less than 70.00 points, then the overall invasive rank should be listed as “Unknown.” †Calculated as 100(a/b) to two decimal places. -

Coastal Processes on Long Island

Shoreline Management on Long Island Coastal Processes on Long Island Coastal Processes Management for ADAPT TO CHANGE Resilient Shorelines MAINTAIN FUNCTION The most appropriate shoreline management RESILIENT option for your shoreline is determined by a SHORELINES WITHSTAND STRESSES number of factors, such as necessity, upland land use, shoreline site conditions, adjacent conditions, ability to be permitted, and others. RECOVER EASILY Costs can be a major consideration for property owners as well. While the cost of some options Artwork by Loriann Cody is mostly for the initial construction, others will require short- or long-term maintenance costs; Proposed construction within the coastal areas therefore, it is important to consider annual and of Long Island requires the property owner to long-term costs when choosing a shoreline apply for permits from local, state and federal management method. agencies. This process may take some time In addition to any associated financial costs, and it is recommended that the applicant there are also considerations of the impacts on contacts the necessary agencies as early as the natural environment and coastal processes. possible. Property owners can also request Some options maintain and/or improve natural pre-application meetings with regulators to coastal processes and features, while others discuss the proposed project. Depending on may negatively impact the natural environment. the complexity of the site or project, property Resilient shorelines tend to work with nature owners can contact a local expert or consultant rather than against it, and are more adaptable that can assist them with understanding and over time to changing conditions. Options that choosing the best option to help stabilize their provide benefits to habitat or coastal processes shorelines and reduce upland risk. -

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- BIBLIOGRAPHY BIBLIOGRAPHY Ackerfield, J., and J. Wen. 2002. A morphometric analysis of Hedera L. (the ivy genus, Araliaceae) and its taxonomic implications. Adansonia 24: 197-212. Adams, P. 1961. Observations on the Sagittaria subulata complex. Rhodora 63: 247-265. Adams, R.M. II, and W.J. Dress. 1982. Nodding Lilium species of eastern North America (Liliaceae). Baileya 21: 165-188. Adams, R.P. 1986. Geographic variation in Juniperus silicicola and J. virginiana of the Southeastern United States: multivariant analyses of morphology and terpenoids. Taxon 35: 31-75. ------. 1995. Revisionary study of Caribbean species of Juniperus (Cupressaceae). Phytologia 78: 134-150. ------, and T. Demeke. 1993. Systematic relationships in Juniperus based on random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs). Taxon 42: 553-571. Adams, W.P. 1957. A revision of the genus Ascyrum (Hypericaceae). Rhodora 59: 73-95. ------. 1962. Studies in the Guttiferae. I. A synopsis of Hypericum section Myriandra. Contr. Gray Herbarium Harv. 182: 1-51. ------, and N.K.B. Robson. 1961. A re-evaluation of the generic status of Ascyrum and Crookea (Guttiferae). Rhodora 63: 10-16. Adams, W.P. 1973. Clusiaceae of the southeastern United States. J. Elisha Mitchell Sci. Soc. 89: 62-71. Adler, L. 1999. Polygonum perfoliatum (mile-a-minute weed). Chinquapin 7: 4. Aedo, C., J.J. Aldasoro, and C. Navarro. 1998. Taxonomic revision of Geranium sections Batrachioidea and Divaricata (Geraniaceae). Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 85: 594-630. Affolter, J.M. 1985. A monograph of the genus Lilaeopsis (Umbelliferae). Systematic Bot. Monographs 6. Ahles, H.E., and A.E. -

Is the Diversity of the Beach Flies Adequately Known? Some Reflections on the State of the Art of Current Knowledge (Diptera: Canacidae)

BOLL. SOC. ENTOMOL. ITAL., 147 (3): 99-111, ISSN 0373-3491 15 DICEMBRE 2015 Lorenzo MuNarI* Is the diversity of the Beach Flies adequately known? Some reflections on the state of the art of current knowledge (Diptera: Canacidae) Riassunto: La diversità delle Beach Flies é adeguatamente conosciuta? Alcune riflessioni sullo stato dell’arte delle attuali conoscenze (Diptera: Canacidae). Viene fornita una panoramica delle maggiori lacune zoogeografiche nella conoscenza dei canacidi appartenenti alle sottofamiglie apetaeninae, Horaismopterinae, Pelomyiinae e Tethininae (tutte conosciute come Beach Flies). Le aree identificate trattate in questo lavoro sono le seguenti: la subartica Beringia, le isole circum-antartiche del Sudamerica, la regione Neotropicale a sud dell’equatore, la maggior parte delle coste marine dell’africa occidentale, l’immensa area che va dall’India, attraverso il Golfo del Bengala, alle isole di Sumatra e Giava, nonché gran parte dell’australia. ad eccezione delle zone inospitali più settentrionali e più meridionali del pianeta, che sono caratterizzate da una reale bio- diversità assai scarsa, le restanti vaste aree trattate in questo lavoro soffrono dolorosamente di una drammatica scarsità di raccolte sul campo, come pure di materiali raccolti nel passato e conservati in istituzioni scientifiche. Ciò potrebbe sembrare un’ovvietà che, pur tuttavia, deve essere enfatizzata allo scopo di identificare in maniera inequivocabile le aree geografiche che richiedono di essere ulteriormente indagate. alla fine della trattazione viene fornita la distribuzione mondiale di tutte le specie citate nel lavoro. Abstract: an overview of the major zoogeographical gaps in our knowledge of the world beach flies (subfamilies apetaeninae, Horaismopteri- nae, Pelomyiinae, and Tethininae) is provided.