Beach Nourishment: Massdep's Guide to Best Management Practices for Projects in Massachusetts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Quick Guide to Southeast Florida's Coral Reefs

A Quick Guide to Southeast Florida’s Coral Reefs DAVID GILLIAM NATIONAL CORAL REEF INSTITUTE NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY Spring 2013 Prepared by the Land-based Sources of Pollution Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) of the Southeast Florida Coral Reef Initiative (SEFCRI) BRIAN WALKER NATIONAL CORAL REEF INSTITUTE, NOVA SOUTHEASTERN Southeast Florida’s coral-rich communities are more valuable than UNIVERSITY the Spanish treasures that sank nearby. Like the lost treasures, these amazing reefs lie just a few hundred yards off the shores of Martin, Palm Beach, Broward and Miami-Dade Counties where more than one-third of Florida’s 19 million residents live. Fishing, diving, and boating help attract millions of visitors to southeast Florida each year (30 million in 2008/2009). Reef-related expen- ditures generate $5.7 billion annually in income and sales, and support more than 61,000 local jobs. Such immense recreational activity, coupled with the pressures of coastal development, inland agriculture, and robust cruise and commercial shipping industries, threaten the very survival of our reefs. With your help, reefs will be protected from local stresses and future generations will be able to enjoy their beauty and economic benefits. Coral reefs are highly diverse and productive, yet surprisingly fragile, ecosystems. They are built by living creatures that require clean, clear seawater to settle, mature and reproduce. Reefs provide safe havens for spectacular forms of marine life. Unfortunately, reefs are vulnerable to impacts on scales ranging from local and regional to global. Global threats to reefs have increased along with expanding ART SEITZ human populations and industrialization. Now, warming seawater temperatures and changing ocean chemistry from carbon dioxide emitted by the burning of fossil fuels and deforestation are also starting to imperil corals. -

Brighton Beach Groynes

CASE STUDY: BRIGHTON BEACH GROYNES BRIGHTON, SOUTH AUSTRALIA FEBRUARY 2017 CLIENT: CITY OF HOLDFAST BAY Adelaide’s beaches are affected by a common phenomenon called ELCOROCK® longshore drift - the flow of water, in one direction, along a beach occurring as a result of winds and currents. In Adelaide longshore drift flows from south to north and it frequently erodes beaches The ELCOROCK system consists of sand- over time, particularly during storm events when tides are high and filled geotextile containers built to form sea is rough. a stabilising, defensive barrier against coastal erosion. Without sand replenishment, the southern end of Adelaide’s beaches will slowly erode and undermine existing infrastructure at The robustness and stability of Elcorock the sea/land interface. The objective of Elcorock sand container geotextile containers provide a solutions groynes, laid perpendicular to the beach, is to capture some of for other marine structures such as groynes and breakwaters. These the natural sand as well as dredged sand, that moves along the structures extend out into the wave zone coast. Over time, this process builds up the beach, particularly and provide marina and beach protection, between the groynes which results in the protection of the existing sand movement control and river training. infrastructure. The size of the container can easily be Geofabrics met with the city of Holdfast Bay in the early stages of selected based on the wave climate and the project to discuss the product, durability and previous projects other conditions ensuring stability under with a similar application. Due to recent weather events, the beach the most extreme conditions. -

A Field Experiment on a Nourished Beach

CHAPTER 157 A Field Experiment on a Nourished Beach A.J. Fernandez* G. Gomez Pina * G. Cuena* J.L. Ramirez* Abstract The performance of a beach nourishment at" Playa de Castilla" (Huel- va, Spain) is evaluated by means of accurate beach profile surveys, vi- sual breaking wave information, buoy-measured wave data and sediment samples. The shoreline recession at the nourished beach due to "profile equilibration" and "spreading out" losses is discussed. The modified equi- librium profile curve proposed by Larson (1991) is shown to accurately describe the profiles with a grain size varying across-shore. The "spread- ing out" losses measured at " Playa de Castilla" are found to be less than predicted by spreading out formulations. The utilization of borrowed material substantially coarser than the native material is suggested as an explanation. 1 INTRODUCTION Fernandez et al. (1990) presented a case study of a sand bypass project at "Playa de Castilla" (Huelva, Spain) and the corresponding monitoring project, that was going to be undertaken. The Beach Nourishment Monitoring Project at the "Playa de Castilla" was begun over two years ago. The project is being *Direcci6n General de Costas. M.O.P.T, Madrid (Spain) 2043 2044 COASTAL ENGINEERING 1992 carried out to evaluate the performance of a beach fill and to establish effective strategies of coastal management and represents one of the most comprehensive monitoring projects that has been undertaken in Spain. This paper summa- rizes and discusses the data set for wave climate, beach profiles and sediment samples. 2 STUDY SITE & MONITORING PROGRAM Playa de Castilla, Fig. 1, is a sandy beach located on the South-West coast of Spain between the Guadiana and Gualdalquivir rivers. -

CITY of MIAMI BEACH DUNE MANAGEMENT PLAN January 2016

CITY OF MIAMI BEACH DUNE MANAGEMENT PLAN January 2016 Prepared by: CITY OF MIAMI BEACH COASTAL MANAGEMENT 1700 Convention Center Drive AND CONSULTING Miami Beach, Florida 33139 7611 Lawrence Road Boynton Beach, Florida 33436 I. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Coastal dunes are habitat for wildlife and support a high biodiversity of flora and fauna. They also keep beaches healthy by accreting sand and minimizing beach erosion rates. The dunes protect coastal infrastructure and upland properties from storm damage by blocking storm surge and absorbing wave energy. Therefore, a healthy dune system is an invaluable asset to coastal communities like Miami Beach. The purpose of the City of Miami Beach Dune Management Plan (“the Plan”) is to outline the framework and specifications that the City will use to foster and maintain a healthy, stable, and natural dune system that is appropriate for its location and reduces public safety and maintenance concerns. The Plan shall guide the City’s efforts in managing the urban, man-made dune as close to a natural system as possible and ensuring the dune provides storm protection, erosion control, and a biologically-rich habitat for local species. II. OBJECTIVES This plan was developed collaboratively with local government and community stakeholders, as well as local experts to meet the following primary objectives: 1. Reduce to the maximum extent possible the presence of invasive, non-native pest plant species within the dune system. Non-native species compete with and overwhelm more stable native dune plants, thereby threatening the stability and biodiversity of the dune system. Reducing the presence of aggressive, non-native vegetation preserves and promotes the structural integrity and biodiversity of the dune. -

Littoral Cells, Sand Budgets, and Beaches: Understanding California S

LITTORAL CELLS, SAND BUDGETS, AND BEACHES: UNDERSTANDING CALIFORNIA’ S SHORELINE KIKI PATSCH GARY GRIGGS OCTOBER 2006 INSTITUTE OF MARINE SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA CRUZ CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF BOATING AND WATERWAYS CALIFORNIA COASTAL SEDIMENT MANAGEMENT WORKGROUP Littoral Cells, Sand Budgets, and Beaches: Understanding California’s Shoreline By Kiki Patch Gary Griggs Institute of Marine Sciences University of California, Santa Cruz California Department of Boating and Waterways California Coastal Sediment Management WorkGroup October 2006 Cover Image: Santa Barbara Harbor © 2002 Kenneth & Gabrielle Adelman, California Coastal Records Project www.californiacoastline.org Brochure Design & Layout Laura Beach www.LauraBeach.net Littoral Cells, Sand Budgets, and Beaches: Understanding California’s Shoreline Kiki Patsch Gary Griggs Institute of Marine Sciences University of California, Santa Cruz TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 7 Chapter 1: Introduction 9 Chapter 2: An Overview of Littoral Cells and Littoral Drift 11 Chapter 3: Elements Involved in Developing Sand Budgets for Littoral Cells 17 Chapter 4: Sand Budgets for California’s Major Littoral Cells and Changes in Sand Supply 23 Chapter 5: Discussion of Beach Nourishment in California 27 Chapter 6: Conclusions 33 References Cited and Other Useful References 35 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he coastline of California can be divided into a set of dis- Beach nourishment or beach restoration is the placement of Ttinct, essentially self-contained littoral cells or beach com- sand on the shoreline with the intent of widening a beach that partments. These compartments are geographically limited and is naturally narrow or where the natural supply of sand has consist of a series of sand sources (such as rivers, streams and been signifi cantly reduced through human activities. -

INTERTIDAL ZONATION Introduction to Oceanography Spring 2017 The

INTERTIDAL ZONATION Introduction to Oceanography Spring 2017 The Intertidal Zone is the narrow belt along the shoreline lying between the lowest and highest tide marks. The intertidal or littoral zone is subdivided broadly into four vertical zones based on the amount of time the zone is submerged. From highest to lowest, they are Supratidal or Spray Zone Upper Intertidal submergence time Middle Intertidal Littoral Zone influenced by tides Lower Intertidal Subtidal Sublittoral Zone permanently submerged The intertidal zone may also be subdivided on the basis of the vertical distribution of the species that dominate a particular zone. However, zone divisions should, in most cases, be regarded as approximate! No single system of subdivision gives perfectly consistent results everywhere. Please refer to the intertidal zonation scheme given in the attached table (last page). Zonal Distribution of organisms is controlled by PHYSICAL factors (which set the UPPER limit of each zone): 1) tidal range 2) wave exposure or the degree of sheltering from surf 3) type of substrate, e.g., sand, cobble, rock 4) relative time exposed to air (controls overheating, desiccation, and salinity changes). BIOLOGICAL factors (which set the LOWER limit of each zone): 1) predation 2) competition for space 3) adaptation to biological or physical factors of the environment Species dominance patterns change abruptly in response to physical and/or biological factors. For example, tide pools provide permanently submerged areas in higher tidal zones; overhangs provide shaded areas of lower temperature; protected crevices provide permanently moist areas. Such subhabitats within a zone can contain quite different organisms from those typical for the zone. -

Appendix 1 : Marine Habitat Types Definitions. Update Of

Appendix 1 Marine Habitat types definitions. Update of “Interpretation Manual of European Union Habitats” COASTAL AND HALOPHYTIC HABITATS Open sea and tidal areas 1110 Sandbanks which are slightly covered by sea water all the time PAL.CLASS.: 11.125, 11.22, 11.31 1. Definition: Sandbanks are elevated, elongated, rounded or irregular topographic features, permanently submerged and predominantly surrounded by deeper water. They consist mainly of sandy sediments, but larger grain sizes, including boulders and cobbles, or smaller grain sizes including mud may also be present on a sandbank. Banks where sandy sediments occur in a layer over hard substrata are classed as sandbanks if the associated biota are dependent on the sand rather than on the underlying hard substrata. “Slightly covered by sea water all the time” means that above a sandbank the water depth is seldom more than 20 m below chart datum. Sandbanks can, however, extend beneath 20 m below chart datum. It can, therefore, be appropriate to include in designations such areas where they are part of the feature and host its biological assemblages. 2. Characteristic animal and plant species 2.1. Vegetation: North Atlantic including North Sea: Zostera sp., free living species of the Corallinaceae family. On many sandbanks macrophytes do not occur. Central Atlantic Islands (Macaronesian Islands): Cymodocea nodosa and Zostera noltii. On many sandbanks free living species of Corallinaceae are conspicuous elements of biotic assemblages, with relevant role as feeding and nursery grounds for invertebrates and fish. On many sandbanks macrophytes do not occur. Baltic Sea: Zostera sp., Potamogeton spp., Ruppia spp., Tolypella nidifica, Zannichellia spp., carophytes. -

Hydrodynamics and Morphodynamics in the Swash Zone: Hydralab Iii Large-Scale Experiments

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI ―FEDERICO II‖ in consorzio con SECONDA UNIVERSITÀ DI NAPOLI UNIVERSITÀ ―PARTHENOPE‖ NAPOLI in convenzione con ISTITUTO PER L‘AMBIENTE MARINO COSTIERO – C.N.R. STAZIONE ZOOLOGICA ―ANTON DOHRN‖ Dottorato in Scienze ed Ingegneria del Mare XXIV ciclo Tesi di Dottorato HYDRODYNAMICS AND MORPHODYNAMICS IN THE SWASH ZONE: HYDRALAB III LARGE-SCALE EXPERIMENTS Relatore: Prof. Diego Vicinanza Co-relatore: Prof. Maurizio Brocchini Candidato: Ing. Pasquale Contestabile Il Coordinatore del Dottorato: Prof. Alberto Incoronato ANNO 2011 ABSTRACT The modelling of swash zone hydrodynamics and sediment transport and the resulting morphodynamics has been an area of very active research over the last decade. However, many details are still to be understood, whose knowledge will be greatly advanced by the collection of high quality data under controlled large-scale laboratory conditions. The advantage of using a large wave flume is that scale effects that affected previous laboratory experiments are minimized. In this work new large-scale laboratory data from two sets of experiments are presented. Physical model tests were performed in the large-scale wave flumes at the Grosser Wellen Kanal (GWK) in Hannover and at the Catalonia University of Technology (UPC) in Barcelona, within the Hydralab III program. The tests carried out at the GWK aimed at improving the knowledge of the hydrodynamic and morphodynamic behaviour of a beach containing a buried drainage system. Experiments were undertaken using a set of multiple drains, up to three working simultaneously, located within the beach and at variable distances from the shoreline. The experimental program was organized in series of tests with variable wave energy. -

Biological Oceanography - Legendre, Louis and Rassoulzadegan, Fereidoun

OCEANOGRAPHY – Vol.II - Biological Oceanography - Legendre, Louis and Rassoulzadegan, Fereidoun BIOLOGICAL OCEANOGRAPHY Legendre, Louis and Rassoulzadegan, Fereidoun Laboratoire d'Océanographie de Villefranche, France. Keywords: Algae, allochthonous nutrient, aphotic zone, autochthonous nutrient, Auxotrophs, bacteria, bacterioplankton, benthos, carbon dioxide, carnivory, chelator, chemoautotrophs, ciliates, coastal eutrophication, coccolithophores, convection, crustaceans, cyanobacteria, detritus, diatoms, dinoflagellates, disphotic zone, dissolved organic carbon (DOC), dissolved organic matter (DOM), ecosystem, eukaryotes, euphotic zone, eutrophic, excretion, exoenzymes, exudation, fecal pellet, femtoplankton, fish, fish lavae, flagellates, food web, foraminifers, fungi, harmful algal blooms (HABs), herbivorous food web, herbivory, heterotrophs, holoplankton, ichthyoplankton, irradiance, labile, large planktonic microphages, lysis, macroplankton, marine snow, megaplankton, meroplankton, mesoplankton, metazoan, metazooplankton, microbial food web, microbial loop, microheterotrophs, microplankton, mixotrophs, mollusks, multivorous food web, mutualism, mycoplankton, nanoplankton, nekton, net community production (NCP), neuston, new production, nutrient limitation, nutrient (macro-, micro-, inorganic, organic), oligotrophic, omnivory, osmotrophs, particulate organic carbon (POC), particulate organic matter (POM), pelagic, phagocytosis, phagotrophs, photoautotorphs, photosynthesis, phytoplankton, phytoplankton bloom, picoplankton, plankton, -

Coastal Processes on Long Island

Shoreline Management on Long Island Coastal Processes on Long Island Coastal Processes Management for ADAPT TO CHANGE Resilient Shorelines MAINTAIN FUNCTION The most appropriate shoreline management RESILIENT option for your shoreline is determined by a SHORELINES WITHSTAND STRESSES number of factors, such as necessity, upland land use, shoreline site conditions, adjacent conditions, ability to be permitted, and others. RECOVER EASILY Costs can be a major consideration for property owners as well. While the cost of some options Artwork by Loriann Cody is mostly for the initial construction, others will require short- or long-term maintenance costs; Proposed construction within the coastal areas therefore, it is important to consider annual and of Long Island requires the property owner to long-term costs when choosing a shoreline apply for permits from local, state and federal management method. agencies. This process may take some time In addition to any associated financial costs, and it is recommended that the applicant there are also considerations of the impacts on contacts the necessary agencies as early as the natural environment and coastal processes. possible. Property owners can also request Some options maintain and/or improve natural pre-application meetings with regulators to coastal processes and features, while others discuss the proposed project. Depending on may negatively impact the natural environment. the complexity of the site or project, property Resilient shorelines tend to work with nature owners can contact a local expert or consultant rather than against it, and are more adaptable that can assist them with understanding and over time to changing conditions. Options that choosing the best option to help stabilize their provide benefits to habitat or coastal processes shorelines and reduce upland risk. -

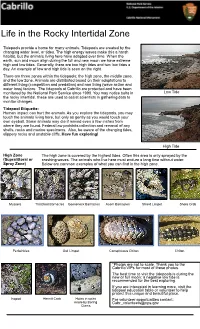

Life in the Intertidal Zone

Life in the Rocky Intertidal Zone Tidepools provide a home for many animals. Tidepools are created by the changing water level, or tides. The high energy waves make this a harsh habitat, but the animals living here have adapted over time. When the earth, sun and moon align during the full and new moon we have extreme high and low tides. Generally, there are two high tides and two low tides a day. An example of low and high tide is seen on the right. There are three zones within the tidepools: the high zone, the middle zone, and the low zone. Animals are distributed based on their adaptations to different living (competition and predation) and non living (wave action and water loss) factors. The tidepools at Cabrillo are protected and have been monitored by the National Park Service since 1990. You may notice bolts in Low Tide the rocky intertidal, these are used to assist scientists in gathering data to monitor changes. Tidepool Etiquette: Human impact can hurt the animals. As you explore the tidepools, you may touch the animals living here, but only as gently as you would touch your own eyeball. Some animals may die if moved even a few inches from where they are found. Federal law prohibits collection and removal of any shells, rocks and marine specimens. Also, be aware of the changing tides, slippery rocks and unstable cliffs. Have fun exploring! High Tide High Zone The high zone is covered by the highest tides. Often this area is only sprayed by the (Supralittoral or crashing waves. -

The Project for Pilot Gravel Beach Nourishment Against Coastal Disaster on Fongafale Island in Tuvalu

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS, TRADES, TOURISM, ENVIRONMENT AND LABOUR THE GOVERNMENT OF TUVALU THE PROJECT FOR PILOT GRAVEL BEACH NOURISHMENT AGAINST COASTAL DISASTER ON FONGAFALE ISLAND IN TUVALU FINAL REPORT (SUPPORTING REPORT) April 2018 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. FUTABA INC. GE JR 18-058 MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS, TRADES, TOURISM, ENVIRONMENT AND LABOUR THE GOVERNMENT OF TUVALU THE PROJECT FOR PILOT GRAVEL BEACH NOURISHMENT AGAINST COASTAL DISASTER ON FONGAFALE ISLAND IN TUVALU FINAL REPORT (SUPPORTING REPORT) April 2018 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. FUTABA INC. Table of Contents Supporting Report-1 Study on the Quality and Quantity of Materials in Phase-1 (quote from Interim Report 1) .............................................................. SR-1 Supporting Report-2 Planning and Design in Phase-1 (quote from Interim Report 1) ............ SR-2 Supporting Report-3 Design Drawing ..................................................................................... SR-3 Supporting Report-4 Project Implementation Plan in Phase-1 (quote from Interim Report 1)................................................................................................. SR-4 Supporting Report-5 Preliminary Environmental Assessment Report (PEAR) ....................... SR-5 Supporting Report-6 Public Consultation in Phase-1 (quote from Interim Report 1) .............. SR-6 Supporting Report-7 Bidding Process (quote from Progress Report) ...................................... SR-7 Supporting