Trauma Team Activation Criteria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recognizing When a Child's Injury Or Illness Is Caused by Abuse

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Recognizing When a Child’s Injury or Illness Is Caused by Abuse PORTABLE GUIDE TO INVESTIGATING CHILD ABUSE U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs 810 Seventh Street NW. Washington, DC 20531 Eric H. Holder, Jr. Attorney General Karol V. Mason Assistant Attorney General Robert L. Listenbee Administrator Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Office of Justice Programs Innovation • Partnerships • Safer Neighborhoods www.ojp.usdoj.gov Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention www.ojjdp.gov The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention is a component of the Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Assistance; the Bureau of Justice Statistics; the National Institute of Justice; the Office for Victims of Crime; and the Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking. Recognizing When a Child’s Injury or Illness Is Caused by Abuse PORTABLE GUIDE TO INVESTIGATING CHILD ABUSE NCJ 243908 JULY 2014 Contents Could This Be Child Abuse? ..............................................................................................1 Caretaker Assessment ......................................................................................................2 Injury Assessment ............................................................................................................4 Ruling Out a Natural Phenomenon or Medical Conditions -

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation

Title: ED Trauma: Trauma Nurse Clinical Resuscitation Document Category: Clinical Document Type: Policy Department/Committee Owner: Practice Council Original Date: Approved By (last review): Director of Emergency Services, Approval Date: 07/28/2014 Trauma Medical Director, Medical Director Emergency (Complete history at end of document.) Services POLICY: To provide immediate, effective and efficient patient care to the trauma patient, designated nursing staff will respond to the trauma room when a trauma page is received. TRAUMA CONTROL NURSE: 1) Role: a) The trauma control nurse (TCN) is a registered nurse (RN) with specialized training in the care of the traumatized patient, and who will function as the trauma team’s lead nurse. b) The TCN shall have successfully completed the Trauma Nurse Core Course (TNCC), Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS), Emergency Nurse Pediatric Course (ENPC) or Pediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), and role orientation with trauma services. c) Full-time employee or regularly scheduled part-time Emergency Department (ED) nurse. d) RN must have 6 months of LMH ED experience. 2) Trauma Control Duties: a) Inspects and stocks trauma room at beginning of each shift and after each trauma patient is discharged from the ED. b) Attempts to maintain trauma room temperature at 80-82 degrees Fahrenheit. c) Communicates with pre-hospital personnel to obtain patient information and prior field treatment and response. d) Makes determination that a patient meets Type I or Type II criteria and immediately notifies LMH’s Call System to initiate the Trauma Activation System. e) Assists physician with orders as directed. f) Acts as liaison with patient’s family/law enforcement/emergency medical services (EMS)/flight crews. -

Delayed Traumatic Hemothorax in Older Adults

Open access Brief report Trauma Surg Acute Care Open: first published as 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000626 on 8 March 2021. Downloaded from Complication to consider: delayed traumatic hemothorax in older adults Jeff Choi ,1 Ananya Anand ,1 Katherine D Sborov,2 William Walton,3 Lawrence Chow,4 Oscar Guillamondegui,5 Bradley M Dennis,5 David Spain,1 Kristan Staudenmayer1 ► Additional material is ABSTRACT very small hemothoraces rarely require interven- published online only. To view, Background Emerging evidence suggests older adults tion whereas larger hemothoraces often undergo please visit the journal online immediate drainage. However, emerging evidence (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ may experience subtle hemothoraces that progress tsaco- 2020- 000626). over several days. Delayed progression and delayed suggests HTX in older adults with rib fractures may development of traumatic hemothorax (dHTX) have not experience subtle hemothoraces that progress in a 1Surgery, Stanford University, been well characterized. We hypothesized dHTX would delayed fashion over several days.1 2 If true, older Stanford, California, USA be infrequent but associated with factors that may aid adults may be at risk of developing empyema or 2Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tennessee, prediction. other complications without close monitoring. USA Methods We retrospectively reviewed adults aged ≥50 Delayed progression and delayed development of 3Radiology, Vanderbilt University years diagnosed with dHTX after rib fractures at two traumatic hemothorax (dHTX) have not been well Medical Center, Nashville, level 1 trauma centers (March 2018 to September 2019). characterized in literature. The ageing US popula- Tennessee, USA tion and increasing incidence of rib fractures among 4Radiology, Stanford University, dHTX was defined as HTX discovered ≥48 hours after Stanford, California, USA admission chest CT showed either no or ’minimal/trace’ older adults underscore a pressing need for better 5Department of Surgery, HTX. -

Injury Surveillance Guidelines

WHO/NMH/VIP/01.02 DISTR.: GENERAL ORIGINAL: ENGLISH INJURY SURVEILLANCE GUIDELINES Edited by: Y Holder, M Peden, E Krug, J Lund, G Gururaj, O Kobusingye Designed by: Health & Development Networks http://www.hdnet.org Published in conjunction with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA, by the World Health Organization 2001 Copies of this document are available from: Injuries and Violence Prevention Department Non-communicable Diseases and Mental Health Cluster World Health Organization 20 Avenue Appia 1211 Geneva 27 Switzerland Fax: 0041 22 791 4332 Email: [email protected] The content of this document is available on the Internet at: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/index.html Suggested citation: Holder Y, Peden M, Krug E et al (Eds). Injury surveillance guidelines. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2001. WHO/NMH/VIP/01.02 © World Health Organization 2001 This document is not a formal publication of the World Health Organization (WHO). All rights are reserved by the Organization. The document may be freely reviewed, abstracted, reproduced or translated, in part or in whole, but may not be sold or used for commercial purposes. The views expressed in documents by named authors are the responsibility of those authors. ii Contents Acronyms .......................................................................................................................... vii Foreword .......................................................................................................................... viii Editorial -

Neurologic Deterioration Secondary to Unrecognized Spinal Instability Following Trauma–A Multicenter Study

SPINE Volume 31, Number 4, pp 451–458 ©2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. Neurologic Deterioration Secondary to Unrecognized Spinal Instability Following Trauma–A Multicenter Study Allan D. Levi, MD, PhD,* R. John Hurlbert, MD, PhD,† Paul Anderson, MD,‡ Michael Fehlings, MD, PhD,§ Raj Rampersaud, MD,§ Eric M. Massicotte, MD,§ John C. France, MD, Jean Charles Le Huec, MD, PhD,¶ Rune Hedlund, MD,** and Paul Arnold, MD†† Study Design. A retrospective study was undertaken their neurologic injury. The most common reason for the that evaluated the medical records and imaging studies of missed injury was insufficient imaging studies (58.3%), a subset of patients with spinal injury from large level I while only 33.3% were a result of misread radiographs or trauma centers. 8.3% poor quality radiographs. The incidence of missed Objective. To characterize patients with spinal injuries injuries resulting in neurologic injury in patients with who had neurologic deterioration due to unrecognized spine fractures or strains was 0.21%, and the incidence as instability. a percentage of all trauma patients evaluated was 0.025%. Summary of Background Data. Controversy exists re- Conclusions. This multicenter study establishes that garding the most appropriate imaging studies required to missed spinal injuries resulting in a neurologic deficit “clear” the spine in patients suspected of having a spinal continue to occur in major trauma centers despite the column injury. Although most bony and/or ligamentous presence of experienced personnel and sophisticated im- spine injuries are detected early, an occasional patient aging techniques. Older age, high impact accidents, and has an occult injury, which is not detected, and a poten- patients with insufficient imaging are at highest risk. -

Mass/Multiple Casualty Triage

9.1 MASS/MULTIPLE CASUALTY TRIAGE PURPOSE · The goal of the mass/multiple Casualty Triage protocol is to prepare for a unified, coordinated, and immediate EMS mutual aid response by prehospital and hospital agencies to effectively expedite the emergency management of the victims of any type of Mass Casualty Incident (MCI). · Successful management of any MCI depends upon the effective cooperation, organization, and planning among health care professionals, hospital administrators and out-of-hospital EMS agencies, state and local government representatives, and individuals and/or organizations associated with disaster-related support agencies. · Adoption of Model Uniform Core Criteria (MUCC). DEFINITIONS Multiple Casualty Situations · The number of patients and the severity of the injuries do not exceed the ability of the provider to render care. Patients with life-threatening injuries are treated first. Mass Casualty Incidents · The number of patients and the severity of the injuries exceed the capability of the provider, and patients sustaining major injuries who have the greatest chance of survival with the least expenditure of time, equipment, supplies, and personnel are managed first. H a z GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS m Initial assessment to include the following: a t · Location of incident. & · Type of incident. M · Any hazards. C · Approximate number of victims. I · Type of assistance required. 9 . 1 COMMUNICATION · Within the scope of a Mass Casualty Incident, the EMS provider may, within the limits of their scope of practice, perform necessary ALS procedures, that under normal circumstances would require a direct physician’s order. · These procedures shall be the minimum necessary to prevent the loss of life or the critical deterioration of a patient’s condition. -

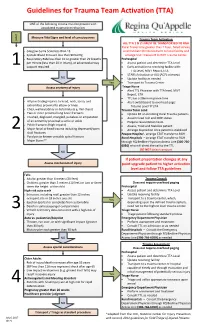

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA)

Guidelines for Trauma Team Activation (TTA) ONE of the following criteria must be present with associated traumatic mechanism L e v e Measure Vital Signs and level of consciousness l Trauma Team Activation ALL TTA 1 & 2's MUST BE TRANSPORTED TO RGH Rural Travel time greater than 1 hour, failed airway · Glasgow Coma Scale less than 13 or immediate life threat divert to local facility and · Systolic Blood Pressure less than 90mmHg arrange STAT transport to RGH Trauma Center · Respiratory Rate less than 10 or greater then 29 breaths Prehospital per minute (less than 20 in infant), or advanced airway · Assess patient and determine TTA Level 1 support required · Early activation to receiving facility with: TTA Level, MIVT Report, ETA · STARS Activation or ALS (ACP) intercept NO · Update facility as needed Yes · Transport to Trauma Center Assess anatomy of injury Triage Nurse · Alert TTL Physician with TTA level, MIVT Report, ETA · TTL has a 20min response time · All penetrating injuries to head, neck, torso, and · Alert switchboard to overhead page: extremities proximal to elbow or knee Trauma Level ‘#’ ETA · Chest wall instability or deformity (e.g. flail chest) Trauma Team Lead · Two or more proximal long-bone fractures · Update ER on incoming Rural Trauma patients · Crushed, degloved, mangled, pulseless or amputation · Assume lead role and MRP status of an extremity proximal to wrist or ankle · Prepare resuscitation team · Pelvic fractures (high impact) · Assess, Treat and Stabilize patient 2 · Major facial or head trauma including depressed/open -

MASS CASUALTY TRAUMA TRIAGE PARADIGMS and PITFALLS July 2019

1 Mass Casualty Trauma Triage - Paradigms and Pitfalls EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Emergency medical services (EMS) providers arrive on the scene of a mass casualty incident (MCI) and implement triage, moving green patients to a single area and grouping red and yellow patients using triage tape or tags. Patients are then transported to local hospitals according to their priority group. Tagged patients arrive at the hospital and are assessed and treated according to their priority. Though this triage process may not exactly describe your agency’s system, this traditional approach to MCIs is the model that has been used to train American EMS As a nation, we’ve got a lot providers for decades. Unfortunately—especially in of trailers with backboards mass violence incidents involving patients with time- and colored tape out there critical injuries and ongoing threats to responders and patients—this model may not be feasible and may result and that’s not what the focus in mis-triage and avoidable, outcome-altering delays of mass casualty response is in care. Further, many hospitals have not trained or about anymore. exercised triage or re-triage of exceedingly large numbers of patients, nor practiced a formalized secondary triage Dr. Edward Racht process that prioritizes patients for operative intervention American Medical Response or transfer to other facilities. The focus of this paper is to alert EMS medical directors and EMS systems planners and hospital emergency planners to key differences between “conventional” MCIs and mass violence events when: • the scene is dynamic, • the number of patients far exceeds usual resources; and • usual triage and treatment paradigms may fail. -

Fat Embolism Syndrome – a Qualitative Review of Its Incidence, Presentation, Pathogenesis and Management

2-RA_OA1 3/24/21 6:00 PM Page 1 Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal 2021 Vol 15 No 1 Timon C, et al doi: https://doi.org/10.5704/MOJ.2103.001 REVIEW ARTICLE Fat Embolism Syndrome – A Qualitative Review of its Incidence, Presentation, Pathogenesis and Management Timon C, MCh, Keady C, MSc, Murphy CG, FRCS Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Galway University Hospitals, Galway, Ireland This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited Date of submission: 12th November 2020 Date of acceptance: 05th March 2021 ABSTRACT DEFINITION AND INTRODUCTION Fat Embolism Syndrome (FES) is a poorly defined clinical Fat embolism 1 occurs when fat enters the circulation, this fat phenomenon which has been attributed to fat emboli entering can embolise and may or may not produce clinical the circulation. It is common, and its clinical presentation manifestations. may be either subtle or dramatic and life threatening. This is a review of the history, causes, pathophysiology, FES is a poorly defined clinical phenomenon which has been presentation, diagnosis and management of FES. FES mostly attributed to fat emboli entering the circulation. It classically occurs secondary to orthopaedic trauma; it is less frequently presents with respiratory, neurological and dermatological associated with other traumatic and atraumatic conditions. features. It typically occurs after long-bone fractures and There is no single test for diagnosing FES. Diagnosis of FES total hip arthroplasty, less frequently it is caused by burns is often missed due to its subclinical presentation and/or and soft tissue injuries 2. -

Physical Injury, PTSD Symptoms, and Medication Use: Examination in Two Trauma Types

Journal of Traumatic Stress February 2014, 27, 74–81 Physical Injury, PTSD Symptoms, and Medication Use: Examination in Two Trauma Types Meghan W. Cody and J. Gayle Beck Department of Psychology, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee, USA Physical injury is prevalent across many types of trauma experiences and can be associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and physical health effects, including increased medication use. Recent studies suggest that PTSD symptoms may mediate the effects of traumatic injury on health outcomes, but it is unknown whether this finding holds for survivors of different types of traumas. The current study examined cross-sectional relationships between injury, PTSD, and pain and psychiatric medication use in 2 trauma- exposed samples, female survivors of motor vehicle accidents (MVAs; n = 315) and intimate partner violence (IPV; n = 167). Data were obtained from participants at 2 trauma research clinics who underwent a comprehensive assessment of psychopathology following the stressor. Regression with bootstrapping suggested that PTSD symptoms mediate the relationship between injury severity and use of pain medications, R2 = .11, F(2, 452) = 28.37, p < .001, and psychiatric medications, R2 = .06, F(2, 452) = 13.18, p < .001, as hypothesized. Mediation, however, was not moderated by trauma type (ps > .05). Results confirm an association between posttraumatic psychopathology and medication usage and suggest that MVA and IPV survivors alike may benefit from assessment and treatment of emotional distress after physical injury. In a recent year, 45.4 million injury-related visits were re- ical health plays in recovery from injury (van der Kolk, Roth, ported at U.S. -

When Treatment Becomes Trauma: Defining, Preventing, and Transforming Medical Trauma

Suggested APA style reference information can be found at http://www.counseling.org/knowledge-center/vistas Article 73 When Treatment Becomes Trauma: Defining, Preventing, and Transforming Medical Trauma Paper based on a program presented at the 2013 American Counseling Association Conference, March 24, Cincinnati, OH. Michelle Flaum Hall and Scott E. Hall Flaum Hall, Michelle, is an assistant professor in Counseling at Xavier University and has written and presented on the topic of medical trauma, post- traumatic growth, and wellness for nine years. Hall, Scott E., is an associate professor in Counselor Education and Human Services at the University of Dayton and has written and presented on trauma, depression, growth, and wellness for 18 years. Abstract Medical trauma, while not a common term in the lexicon of the health professions, is a phenomenon that deserves the attention of mental and physical healthcare providers. Trauma experienced as a result of medical procedures, illnesses, and hospital stays can have lasting effects. Those who experience medical trauma can develop clinically significant reactions such as PTSD, anxiety, depression, complicated grief, and somatic complaints. In addition to clinical disorders, secondary crises—including developmental, physical, existential, relational, occupational, spiritual, and of self—can lead people to seek counseling for ongoing support, growth, and healing. While counselors are central in treating the aftereffects of medical trauma and helping clients experience posttraumatic growth, the authors suggest the importance of mental health practitioners in the prevention and assessment of medical trauma within an integrated health paradigm. The prevention and treatment of trauma-related illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have been of increasing concern to health practitioners and policy makers in the United States (Tedstone & Tarrier, 2003). -

UHS Adult Major Trauma Guidelines 2014

Adult Major Trauma Guidelines University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust Version 1.1 Dr Andy Eynon Director of Major Trauma, Consultant in Neurosciences Intensive Care Dr Simon Hughes Deputy Director of Major Trauma, Consultant Anaesthetist Dr Elizabeth Shewry Locum Consultant Anaesthetist in Major Trauma Version 1 Dr Andy Eynon Dr Simon Hughes Dr Elizabeth ShewryVersion 1 1 UHS Adult Major Trauma Guidelines 2014 NOTE: These guidelines are regularly updated. Check the intranet for the latest version. DO NOT PRINT HARD COPIES Please note these Major Trauma Guidelines are for UHS Adult Major Trauma Patients. The Wessex Children’s Major Trauma Guidelines may be found at http://staffnet/TrustDocsMedia/DocsForAllStaff/Clinical/Childr ensMajorTraumaGuideline/Wessexchildrensmajortraumaguid eline.doc NOTE: If you are concerned about a patient under the age of 16 please contact SORT (02380 775502) who will give valuable clinical advice and assistance by phone to the Trauma Unit and coordinate any transfer required. http://www.sort.nhs.uk/home.aspx Please note current versions of individual University Hospital South- ampton Major Trauma guidelines can be found by following the link below. http://staffnet/TrustDocuments/Departmentanddivision- specificdocuments/Major-trauma-centre/Major-trauma-centre.aspx Version 1 Dr Andy Eynon Dr Simon Hughes Dr Elizabeth Shewry 2 UHS Adult Major Trauma Guidelines 2014 Contents Please ‘control + click’ on each ‘Section’ below to link to individual sections. Section_1: Preparation for Major Trauma Admissions