Threatened Fauna in Box-Ironbark

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yellow Bellied Glider

Husbandry Manual for the Yellow-Bellied Glider Petaurus australis [Mammalia / Petauridae] Liana Carroll December 2005 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond 1068 Certificate III Captive Animals Lecturer: Graeme Phipps TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................... 5 2 TAXONOMY ...................................................................................................................................... 6 2.1 NOMENCLATURE .......................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 SUBSPECIES .................................................................................................................................. 6 2.3 RECENT SYNONYMS ..................................................................................................................... 6 2.4 OTHER COMMON NAMES ............................................................................................................. 6 3 NATURAL HISTORY ....................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 MORPHOMETRICS ......................................................................................................................... 8 3.1.1 Mass And Basic Body Measurements ..................................................................................... 8 3.1.2 Sexual Dimorphism ................................................................................................................ -

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

Squirrel Glider Petaurus Norfolcensis Review of Current Information in NSW August 2008

NSW SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Squirrel Glider Petaurus norfolcensis Review of Current Information in NSW August 2008 Current status: The Squirrel Glider Petaurus norfolcensis is currently listed as Threatened in Victoria under the Flora & Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (FFG Act; Endangered on the Advisory List), and Endangered in South Australia under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 (NPW Act). This species is not listed under Commonwealth legislation. The NSW Scientific Committee recently determined that the Squirrel Glider meets criteria for listing as Vulnerable in NSW under the Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (TSC Act), based on information contained in this report and other information available for the species. Two Endangered Populations of Squirrel Gliders are also listed in NSW; one on the Barrenjoey Peninsula, and one in the Wagga Wagga Local Government Area. Species description: The Squirrel Glider is a medium-sized glider, with a thick furry tail, almost twice the size of the Sugar Glider Petaurus breviceps; head-body length 17-24 cm, tail 22-30 cm, weight 190-330 g. The upperparts are grey with a black dorsal stripe from crown to rump, black markings around the ears, and a black border to the gliding membrane; the terminal third to half of the tail is black, and the underparts are white. The smaller Sugar Glider is very similar (head-body 16-20 cm, tail 17-21 cm, weight 90-150 g), but is more snub-nosed with less bold black markings, has pale grey or cream rather than clean white underparts, and the less tapered tail is black on the terminal quarter, sometimes with a white tip. -

The Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus Occidentalis)

A major road and an artificial waterway are barriers to the rapidly declining western ringtail possum, Pseudocheirus occidentalis Kaori Yokochi BSc. (Hons.) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Animal Biology Faculty of Science October 2015 Abstract Roads are known to pose negative impacts on wildlife by causing direct mortality, habitat destruction and habitat fragmentation. Other kinds of artificial linear structures, such as railways, powerline corridors and artificial waterways, have the potential to cause similar negative impacts. However, their impacts have been rarely studied, especially on arboreal species even though these animals are thought to be highly vulnerable to the effects of habitat fragmentation due to their fidelity to canopies. In this thesis, I studied the effects of a major road and an artificial waterway on movements and genetics of an endangered arboreal species, the western ringtail possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis). Despite their endangered status and recent dramatic decline, not a lot is known about this species mainly because of the difficulties in capturing them. Using a specially designed dart gun, I captured and radio tracked possums over three consecutive years to study their movement and survival along Caves Road and an artificial waterway near Busselton, Western Australia. I studied the home ranges, dispersal pattern, genetic diversity and survival, and performed population viability analyses on a population with one of the highest known densities of P. occidentalis. I also carried out simulations to investigate the consequences of removing the main causes of mortality in radio collared adults, fox predation and road mortality, in order to identify effective management options. -

Kangaroos, Dendrolagus Matschiei (Macropodidae), in Upper Montane Forest

Spatial Requirements of Free-Ranging Huon Tree Kangaroos, Dendrolagus matschiei (Macropodidae), in Upper Montane Forest Gabriel Porolak1,2,3*, Lisa Dabek3, Andrew K. Krockenberger1,2 1 Centre for Tropical Biodiversity and Climate Change, James Cook University, Cairns, Australia, 2 School of Marine and Tropical Biology, James Cook University, Cairns, Australia, 3 Department of Field Conservation, Woodland Park Zoo, Seattle, Washington, United States of America Abstract Tree kangaroos (Macropodidae, Dendrolagus) are some of Australasia’s least known mammals. However, there is sufficient evidence of population decline and local extinctions that all New Guinea tree kangaroos are considered threatened. Understanding spatial requirements is important in conservation and management. Expectations from studies of Australian tree kangaroos and other rainforest macropodids suggest that tree kangaroos should have small discrete home ranges with the potential for high population densities, but there are no published estimates of spatial requirements of any New Guinea tree kangaroo species. Home ranges of 15 Huon tree kangaroos, Dendrolagus matschiei, were measured in upper montane forest on the Huon Peninsula, Papua New Guinea. The home range area was an average of 139.6626.5 ha (100% MCP; n = 15) or 81.8628.3 ha (90% harmonic mean; n = 15), and did not differ between males and females. Home ranges of D. matschiei were 40–100 times larger than those of Australian tree kangaroos or other rainforest macropods, possibly due to the impact of hunting reducing density, or low productivity of their high altitude habitat. Huon tree kangaroos had cores of activity within their range at 45% (20.964.1 ha) and 70% (36.667.5 ha) harmonic mean isopleths, with little overlap (4.862.9%; n = 15 pairs) between neighbouring females at the 45% isopleth, but, unlike the Australian species, extensive overlap between females (20.865.5%; n = 15 pairs) at the complete range (90% harmonic mean). -

A Preliminary Risk Assessment of Cane Toads in Kakadu National Park Scientist Report 164, Supervising Scientist, Darwin NT

supervising scientist 164 report A preliminary risk assessment of cane toads in Kakadu National Park RA van Dam, DJ Walden & GW Begg supervising scientist national centre for tropical wetland research This report has been prepared by staff of the Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist (eriss) as part of our commitment to the National Centre for Tropical Wetland Research Rick A van Dam Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, Locked Bag 2, Jabiru NT 0886, Australia (Present address: Sinclair Knight Merz, 100 Christie St, St Leonards NSW 2065, Australia) David J Walden Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801, Australia George W Begg Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801, Australia This report should be cited as follows: van Dam RA, Walden DJ & Begg GW 2002 A preliminary risk assessment of cane toads in Kakadu National Park Scientist Report 164, Supervising Scientist, Darwin NT The Supervising Scientist is part of Environment Australia, the environmental program of the Commonwealth Department of Environment and Heritage © Commonwealth of Australia 2002 Supervising Scientist Environment Australia GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801 Australia ISSN 1325-1554 ISBN 0 642 24370 0 This work is copyright Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Supervising Scientist Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction -

Mahogany Glider Complex

ResearchOnline@JCU This file is part of the following reference: Ferraro, Paul Anthony (2012) A phylogeographic and taxonomic assessment of the squirrel - mahogany glider complex. Masters (Research) thesis, James Cook University. Access to this file is available from: http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/29137/ The author has certified to JCU that they have made a reasonable effort to gain permission and acknowledge the owner of any third party copyright material included in this document. If you believe that this is not the case, please contact [email protected] and quote http://eprints.jcu.edu.au/29137/ A phylogeographic and taxonomic assessment of the squirrel – mahogany glider complex Thesis submitted by Paul Anthony FERRARO BSc (Hons) In August 2012 For the degree of Master of Science In the School of Marine and Tropical Biology James Cook University DECLARATIONS Declarations Statement of Access I, the undersigned, the author of this thesis, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library and Australian Digital Thesis Network for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act and; I do not wish to place any further restrictions on access to this work. Statement of Sources I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. -

OWLS of OHIO C D G U I D E B O O K DIVISION of WILDLIFE Introduction O W L S O F O H I O

OWLS OF OHIO c d g u i d e b o o k DIVISION OF WILDLIFE Introduction O W L S O F O H I O Owls have longowls evoked curiosity in In the winter of of 2002, a snowy ohio owl and stygian owl are known from one people, due to their secretive and often frequented an area near Wilmington and two Texas records, respectively. nocturnal habits, fierce predatory in Clinton County, and became quite Another, the Oriental scops-owl, is behavior, and interesting appearance. a celebrity. She was visited by scores of known from two Alaska records). On Many people might be surprised by people – many whom had never seen a global scale, there are 27 genera of how common owls are; it just takes a one of these Arctic visitors – and was owls in two families, comprising a total bit of knowledge and searching to find featured in many newspapers and TV of 215 species. them. The effort is worthwhile, as news shows. A massive invasion of In Ohio and abroad, there is great owls are among our most fascinating northern owls – boreal, great gray, and variation among owls. The largest birds, both to watch and to hear. Owls Northern hawk owl – into Minnesota species in the world is the great gray are also among our most charismatic during the winter of 2004-05 became owl of North America. It is nearly three birds, and reading about species with a major source of ecotourism for the feet long with a wingspan of almost 4 names like fearful owl, barking owl, North Star State. -

Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles Acutipennis

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Evolution of Quiet Flight in Owls (Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles acutipennis) A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology by Krista Le Piane December 2020 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin Dr. Khaleel A. Razak Copyright by Krista Le Piane 2020 The Dissertation of Krista Le Piane is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my Oral Exam Committee: Dr. Khaleel A. Razak (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, Dr. Mark Springer, Dr. Jesse Barber, and Dr. Scott Curie. Thank you to my Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, and Dr. Khaleel A. Razak for their encouragement and help with this dissertation. Thank you to my lab mates, past and present: Dr. Sean Wilcox, Dr. Katie Johnson, Ayala Berger, David Rankin, Dr. Nadje Najar, Elisa Henderson, Dr. Brian Meyers Dr. Jenny Hazelhurst, Emily Mistick, Lori Liu, and Lilly Hollingsworth for their friendship and support. I thank the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (LACM), the California Academy of Sciences (CAS), Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) at UC Berkeley, the American Museum of Natural History (ANMH), and the Natural History Museum (NHM) in Tring for access to specimens used in Chapter 1. I would especially like to thank Kimball Garrett and Allison Shultz for help at LACM. I also thank Ben Williams, Richard Jackson, and Reddit user NorthernJoey for permission to use their photos in Chapter 1. Jessica Tingle contributed R code and advice to Chapter 1 and I would like to thank her for her help. -

The Status of Threatened Bird Species in the Hunter Region

!"#$%&$'$()*+#(),-$.+$,)/0'&$#)1$2+3') !"$)4"+,&5$#)!"#$%&%'6)789:) The status of threatened bird species in the Hunter Region Michael Roderick1 and Alan Stuart2 156 Karoola Road, Lambton, NSW 2299 281 Queens Road, New Lambton, NSW 2305 ) ;%'<)*+#(),-$.+$,)5+,&$()%,)=05'$#%*5$>)?'(%'2$#$()3#)@#+&+.%55<)?'(%'2$#$()A.355$.&+B$5<)#$C$##$()&3)%,) !"#$%&"%'%()*+,'(%$+"#%+!"#$%&$'$()*+$,-$.)/0'.$#1%&-0')2,&)3445)ADE4F)have been recorded within the Hunter Region. The majority are resident or regular migrants. Some species are vagrants, and some seabirds) #$205%#5<) -#$,$'&) %#$) '3&) #$5+%'&) 3') &"$) 1$2+3') C3#) ,0#B+B%5G) !"$) %0&"3#,) "%B$) #$B+$H$() &"$) #$2+3'%5),&%&0,)3C)%55),-$.+$,>)H+&")-%#&+.05%#)C3.0,)3')&"$)#$,+($'&,)%'()#$205%#)B+,+&3#,G)!"$).3',$#B%&+3') ,&%&0,)C3#)$%."),-$.+$,)+,)2+B$'>)+'.50(+'2)H"$#$)#$5$B%'&)&"$),&%&0,)0'($#)&"$)Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) review. R$.$'&)#$.3#(,)C3#)&"$)1$2+3')%#$).3I-%#$()H+&")-#$B+30,)-$#+3(,>)53.%5)&"#$%&,) %#$)#$B+$H$()%'()&"$)30&533J)C3#)$%."),-$.+$,)+,)(+,.0,,$(G)) ) ) INTRODUCTION is relevant. The two measures of conservation status are: The Threatened Species Conservation (TSC) Act 1995 is the primary legislation for the protection of The Environment Protection and Biodiversity threatened flora and fauna species in NSW. The Conservation (EPBC) Act 1999 is the NSW Scientific Committee is the key group equivalent threatened species legislation at the responsible for the review of the conservation Commonwealth level. status of threatened species, including the listing of those species. More than 100 bird species are A measure of conservation status that can also listed as threatened under the TSC Act, and the be applied at sub-species level was developed Scientific Committee supports the listing of by the International Union for Conservation of additional species. -

Fauna Monitoring in the Karri Forests of Western Australia

E R N V M E O N G T E O H F T W A E I S L T A E R R N A U S T Fauna monitoring in the karri forests of Western Australia Fauna monitoring training manual - July 2018 Prepared for the Forest Products Commission Karlene Bain, Python Ecological Services Cover image provided by Karlene Bain. Citation: Bain, K. (2018). Training Manual: Fauna Monitoring in the Karri Forests of Western Australia. Forest Products Commission, Western Australia. Perth Karlene Bain BSc MSc PhD Director Python Ecological Services PO Box 168 Walpole 6398 Email: draconis.wn.com.au Copyright © 2018, Forest Products Commission. All rights reserved. All materials; including internet pages, documents and on-line graphics, audio and video are protected by copyright law. Copyright of these materials resides with the State of Western Australia. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced or re-used for any purposes whatsoever without prior written permission of the General Manager, Forest Products Commission. Permission to use these materials can be obtained by contacting: Copyright Officer Forest Products Commission Locked Bag 888 PERTH BUSINESS CENTRE WA 6849 AUSTRALIA Telephone: +61 8 9363 4600 Internet: www.fpc.wa.gov.au Email: [email protected] Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this report reflect those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Forest Products Commission. The information contained in this publication is based on knowledge and understanding at the time of writing. -

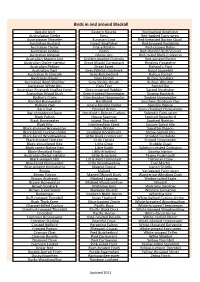

Birds in and Around Blackall

Birds in and around Blackall Apostle bird Eastern Rosella Red backed Kingfisher Australasian Grebe Emu Red-backed Fairy-wren Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Red-breasted Button Quail Australian Bustard Forest Kingfisher Red-browed Pardalote Australian Darter Friary Martin Red-capped Robin Australian Hobby Galah Red-chested Buttonquail Australian Magpie Glossy Ibis Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Australian Magpie-lark Golden-headed Cisticola Red-winged Parrot Australian Owlet-nightjar Great (Black) Cormorant Restless Flycatcher Australian Pelican Great Egret Richard’s Pipit Australian Pipit Grey (White) Goshawk Royal Spoonbill Australian Pratincole Grey Butcherbird Rufous Fantail Australian Raven Grey Fantail Rufous Songlark Australian Reed Warbler Grey Shrike-thrush Rufous Whistler Australian White Ibis Grey Teal Sacred Ibis Australian Ringneck (mallee form) Grey-crowned Babbler Sacred Kingfisher Australian Wood Duck Grey-fronted Honeyeater Singing Bushlark Baillon’s Crake Grey-headed Honeyeater Singing Honeyeater Banded Honeyeater Hardhead Southern Boobook Owl Barking Owl Hoary-headed Grebe Spinifex Pigeon Barn Owl Hooded Robin Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Bar-shouldered Dove Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Splendid Fairy-wren Black Falcon House Sparrow Spotted Bowerbird Black Honeyeater Inland Thornbill Spotted Nightjar Black Kite Intermediate Egret Square-tailed kite Black-chinned Honeyeater Jacky Winter Squatter Pigeon Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Laughing Kookaburra Straw-necked Ibis Black-faced Woodswallow Little Black Cormorant Striated Pardalote