Barking Owl Ninox Connivens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Preliminary Risk Assessment of Cane Toads in Kakadu National Park Scientist Report 164, Supervising Scientist, Darwin NT

supervising scientist 164 report A preliminary risk assessment of cane toads in Kakadu National Park RA van Dam, DJ Walden & GW Begg supervising scientist national centre for tropical wetland research This report has been prepared by staff of the Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist (eriss) as part of our commitment to the National Centre for Tropical Wetland Research Rick A van Dam Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, Locked Bag 2, Jabiru NT 0886, Australia (Present address: Sinclair Knight Merz, 100 Christie St, St Leonards NSW 2065, Australia) David J Walden Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801, Australia George W Begg Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist, GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801, Australia This report should be cited as follows: van Dam RA, Walden DJ & Begg GW 2002 A preliminary risk assessment of cane toads in Kakadu National Park Scientist Report 164, Supervising Scientist, Darwin NT The Supervising Scientist is part of Environment Australia, the environmental program of the Commonwealth Department of Environment and Heritage © Commonwealth of Australia 2002 Supervising Scientist Environment Australia GPO Box 461, Darwin NT 0801 Australia ISSN 1325-1554 ISBN 0 642 24370 0 This work is copyright Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Supervising Scientist Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction -

OWLS of OHIO C D G U I D E B O O K DIVISION of WILDLIFE Introduction O W L S O F O H I O

OWLS OF OHIO c d g u i d e b o o k DIVISION OF WILDLIFE Introduction O W L S O F O H I O Owls have longowls evoked curiosity in In the winter of of 2002, a snowy ohio owl and stygian owl are known from one people, due to their secretive and often frequented an area near Wilmington and two Texas records, respectively. nocturnal habits, fierce predatory in Clinton County, and became quite Another, the Oriental scops-owl, is behavior, and interesting appearance. a celebrity. She was visited by scores of known from two Alaska records). On Many people might be surprised by people – many whom had never seen a global scale, there are 27 genera of how common owls are; it just takes a one of these Arctic visitors – and was owls in two families, comprising a total bit of knowledge and searching to find featured in many newspapers and TV of 215 species. them. The effort is worthwhile, as news shows. A massive invasion of In Ohio and abroad, there is great owls are among our most fascinating northern owls – boreal, great gray, and variation among owls. The largest birds, both to watch and to hear. Owls Northern hawk owl – into Minnesota species in the world is the great gray are also among our most charismatic during the winter of 2004-05 became owl of North America. It is nearly three birds, and reading about species with a major source of ecotourism for the feet long with a wingspan of almost 4 names like fearful owl, barking owl, North Star State. -

Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles Acutipennis

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Evolution of Quiet Flight in Owls (Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles acutipennis) A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology by Krista Le Piane December 2020 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin Dr. Khaleel A. Razak Copyright by Krista Le Piane 2020 The Dissertation of Krista Le Piane is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my Oral Exam Committee: Dr. Khaleel A. Razak (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, Dr. Mark Springer, Dr. Jesse Barber, and Dr. Scott Curie. Thank you to my Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, and Dr. Khaleel A. Razak for their encouragement and help with this dissertation. Thank you to my lab mates, past and present: Dr. Sean Wilcox, Dr. Katie Johnson, Ayala Berger, David Rankin, Dr. Nadje Najar, Elisa Henderson, Dr. Brian Meyers Dr. Jenny Hazelhurst, Emily Mistick, Lori Liu, and Lilly Hollingsworth for their friendship and support. I thank the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (LACM), the California Academy of Sciences (CAS), Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) at UC Berkeley, the American Museum of Natural History (ANMH), and the Natural History Museum (NHM) in Tring for access to specimens used in Chapter 1. I would especially like to thank Kimball Garrett and Allison Shultz for help at LACM. I also thank Ben Williams, Richard Jackson, and Reddit user NorthernJoey for permission to use their photos in Chapter 1. Jessica Tingle contributed R code and advice to Chapter 1 and I would like to thank her for her help. -

The Status of Threatened Bird Species in the Hunter Region

!"#$%&$'$()*+#(),-$.+$,)/0'&$#)1$2+3') !"$)4"+,&5$#)!"#$%&%'6)789:) The status of threatened bird species in the Hunter Region Michael Roderick1 and Alan Stuart2 156 Karoola Road, Lambton, NSW 2299 281 Queens Road, New Lambton, NSW 2305 ) ;%'<)*+#(),-$.+$,)5+,&$()%,)=05'$#%*5$>)?'(%'2$#$()3#)@#+&+.%55<)?'(%'2$#$()A.355$.&+B$5<)#$C$##$()&3)%,) !"#$%&"%'%()*+,'(%$+"#%+!"#$%&$'$()*+$,-$.)/0'.$#1%&-0')2,&)3445)ADE4F)have been recorded within the Hunter Region. The majority are resident or regular migrants. Some species are vagrants, and some seabirds) #$205%#5<) -#$,$'&) %#$) '3&) #$5+%'&) 3') &"$) 1$2+3') C3#) ,0#B+B%5G) !"$) %0&"3#,) "%B$) #$B+$H$() &"$) #$2+3'%5),&%&0,)3C)%55),-$.+$,>)H+&")-%#&+.05%#)C3.0,)3')&"$)#$,+($'&,)%'()#$205%#)B+,+&3#,G)!"$).3',$#B%&+3') ,&%&0,)C3#)$%."),-$.+$,)+,)2+B$'>)+'.50(+'2)H"$#$)#$5$B%'&)&"$),&%&0,)0'($#)&"$)Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) review. R$.$'&)#$.3#(,)C3#)&"$)1$2+3')%#$).3I-%#$()H+&")-#$B+30,)-$#+3(,>)53.%5)&"#$%&,) %#$)#$B+$H$()%'()&"$)30&533J)C3#)$%."),-$.+$,)+,)(+,.0,,$(G)) ) ) INTRODUCTION is relevant. The two measures of conservation status are: The Threatened Species Conservation (TSC) Act 1995 is the primary legislation for the protection of The Environment Protection and Biodiversity threatened flora and fauna species in NSW. The Conservation (EPBC) Act 1999 is the NSW Scientific Committee is the key group equivalent threatened species legislation at the responsible for the review of the conservation Commonwealth level. status of threatened species, including the listing of those species. More than 100 bird species are A measure of conservation status that can also listed as threatened under the TSC Act, and the be applied at sub-species level was developed Scientific Committee supports the listing of by the International Union for Conservation of additional species. -

Fauna Monitoring in the Karri Forests of Western Australia

E R N V M E O N G T E O H F T W A E I S L T A E R R N A U S T Fauna monitoring in the karri forests of Western Australia Fauna monitoring training manual - July 2018 Prepared for the Forest Products Commission Karlene Bain, Python Ecological Services Cover image provided by Karlene Bain. Citation: Bain, K. (2018). Training Manual: Fauna Monitoring in the Karri Forests of Western Australia. Forest Products Commission, Western Australia. Perth Karlene Bain BSc MSc PhD Director Python Ecological Services PO Box 168 Walpole 6398 Email: draconis.wn.com.au Copyright © 2018, Forest Products Commission. All rights reserved. All materials; including internet pages, documents and on-line graphics, audio and video are protected by copyright law. Copyright of these materials resides with the State of Western Australia. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced or re-used for any purposes whatsoever without prior written permission of the General Manager, Forest Products Commission. Permission to use these materials can be obtained by contacting: Copyright Officer Forest Products Commission Locked Bag 888 PERTH BUSINESS CENTRE WA 6849 AUSTRALIA Telephone: +61 8 9363 4600 Internet: www.fpc.wa.gov.au Email: [email protected] Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this report reflect those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Forest Products Commission. The information contained in this publication is based on knowledge and understanding at the time of writing. -

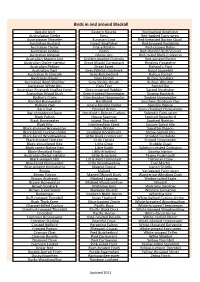

Birds in and Around Blackall

Birds in and around Blackall Apostle bird Eastern Rosella Red backed Kingfisher Australasian Grebe Emu Red-backed Fairy-wren Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Red-breasted Button Quail Australian Bustard Forest Kingfisher Red-browed Pardalote Australian Darter Friary Martin Red-capped Robin Australian Hobby Galah Red-chested Buttonquail Australian Magpie Glossy Ibis Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Australian Magpie-lark Golden-headed Cisticola Red-winged Parrot Australian Owlet-nightjar Great (Black) Cormorant Restless Flycatcher Australian Pelican Great Egret Richard’s Pipit Australian Pipit Grey (White) Goshawk Royal Spoonbill Australian Pratincole Grey Butcherbird Rufous Fantail Australian Raven Grey Fantail Rufous Songlark Australian Reed Warbler Grey Shrike-thrush Rufous Whistler Australian White Ibis Grey Teal Sacred Ibis Australian Ringneck (mallee form) Grey-crowned Babbler Sacred Kingfisher Australian Wood Duck Grey-fronted Honeyeater Singing Bushlark Baillon’s Crake Grey-headed Honeyeater Singing Honeyeater Banded Honeyeater Hardhead Southern Boobook Owl Barking Owl Hoary-headed Grebe Spinifex Pigeon Barn Owl Hooded Robin Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Bar-shouldered Dove Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Splendid Fairy-wren Black Falcon House Sparrow Spotted Bowerbird Black Honeyeater Inland Thornbill Spotted Nightjar Black Kite Intermediate Egret Square-tailed kite Black-chinned Honeyeater Jacky Winter Squatter Pigeon Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Laughing Kookaburra Straw-necked Ibis Black-faced Woodswallow Little Black Cormorant Striated Pardalote -

Eton Range Realignment Project ATTACHMENT 2 to EPBC Ref: 2015/7552 Preliminary Documentation Residual Impact Assessment and Offset Proposal - 37

APPENDIX 3: KSAT RESULTS – PELLET COUNTS Table 5: KSAT results per habitat tree. Species Site 1 Site 2 Site 3 Site 4 Site 5 Site 6 Total Eucalyptus tereticornis 9 30 16 - 42 7 104 Eucalyptus crebra 91 16 29 2 0 25 163 Corymbia clarksoniana 11 0 0 1 4 5 21 Corymbia tessellaris 5 0 0 0 0 20 25 Corymbia dallachiana - 12 - - - - 12 Corymbia intermedia - 3 1 0 11 - 15 Corymbia erythrophloia - - 0 - 0 - 0 Eucalyptus platyphylla - - - 0 0 0 0 Lophostemon - - - 0 0 - 0 suaveolens Total 116 61 46 3 57 57 Ref: NCA15R30439 Page 22 27 November 2015 Copyright 2015 Kleinfelder APPENDIX 4: SITE PHOTOS The following images were taken from the centre of each BioCondition quadrat and represent a north east south west aspect, top left to bottom right. Ref: NCA15R30439 Page 23 27 November 2015 Copyright 2015 Kleinfelder Plate 3: BioCondition quadrat 1 (RE11.3.4/11.12.3) Ref: NCA15R30439 Page 24 27 November 2015 Copyright 2015 Kleinfelder Plate 4: BioCondition quadrat 2 (RE11.3.4/11.12.3) Ref: NCA15R30439 Page 25 27 November 2015 Copyright 2015 Kleinfelder Plate 5: BioCondition quadrat 3 (RE11.12.3) Ref: NCA15R30439 Page 26 27 November 2015 Copyright 2015 Kleinfelder Plate 6: BioCondition quadrat 4 (RE11.3.9) Ref: NCA15R30439 Page 27 27 November 2015 Copyright 2015 Kleinfelder Plate 7: BioCondition quadrat 5 (RE11.3.25) Ref: NCA15R30439 Page 28 27 November 2015 Copyright 2015 Kleinfelder Plate 8: BioCondition quadrat 6 (RE11.12.3/11.3.4/11.3.9) Ref: NCA15R30439 Page 29 27 November 2015 Copyright 2015 Kleinfelder Appendix E: Desktop Assessment for Potential -

Dry Season Diet of a Barking Owl Ninox Connivens Peninsularis on Adolphus Island in the North of Western Australia

Corella, 2016, 40(4): 101-102 Dry season diet of a Barking Owl Ninox connivens peninsularis on Adolphus Island in the north of Western Australia Russell Palmer1* and Wesley Caton1, 2 1Science and Conservation Division, Department of Parks and Wildlife, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Western Australia, 6983. 2 Evolution Fauna Consultancy, 29 Tugun Street, Tugun, Queensland, 4224. *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Received: 22 December 2015 The Barking Owl Ninox connivens is a medium-sized hawk- Adolphus Island (4138 ha), which is situated in the southern owl that is associated with the open forest and woodland section of Cambridge Gulf, 35 kilometres north of Wyndham. environments of mainland Australia (Higgins 1999). Two The vegetation is dominated by open eucalypt woodlands, subspecies are recognised. The larger N. c. connivens (males Acacia shrublands, grasslands and fringing, low-lying mud flats 695 g, females 592 g) occurs in southern and eastern Australia, with extensive areas of mangal (mangrove swamp forest). whilst the smaller N. c. peninsularis (males 501 g, females 440 g) is restricted to the north of the continent (Higgins 1999). The Standard survey techniques were used to record the island’s Barking Owl is common in the wet-dry tropics, but uncommon vertebrate fauna (details in Gibson et al. 2015). to rare and declining in the temperate zone (Debus 2009; Parker et al. 2007). A single Barking Owl was observed on three occasions roosting in a cluster of fig trees Ficus atricha (15°06’33”S, Fleay (1968) described the species as a robust and versatile 128°09’07”E), under which seven fresh, egested pellets were owl. -

Holbrook Bird List

Holbrook Bird List Diurnal birds Australian Hobby Grey Currawong Shining Bronze-Cuckoo Australian King Parrot Grey Fantail Silvereye Australian Magpie Grey Shrike-thrush Southern Whiteface Australian Raven Grey-crowned Babbler Speckled Warbler Australian Reed-Warbler Hooded Robin Spotted Harrier Black-chinned Honeyeater Horsfield's Bronze-cuckoo Spotted Pardalote Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Jacky Winter Spotted Quail-thrush Black-shouldered Kite Laughing Kookaburra Striated Pardalote Blue-faced Honeyeater Leaden Flycatcher Striated Thornbill Brown Falcon Little Corella Stubble Quail Brown Goshawk Little Eagle Sulphur-crested Cockatoo Brown Quail Little Friarbird Superb Fairy-wren Brown Songlark Little Lorikeet Swamp Harrier Brown Thornbill Magpie-lark Swift Parrot (e) Brown Treecreeper Mistletoebird Tree Martin Brown-headed Honeyeater Nankeen Kestrel Turquoise Parrot (t) Buff-rumped Thornbill Noisy Friarbird Varied Sitella Cockatiel Noisy Miner Wedge-tailed Eagle Common Bronzewing Olive-backed Oriole Weebill Common Starling * Painted Button Quail Welcome Swallow Crested Pigeon Painted Honeyeater (t) Western Warbler Crested Shrike-tit Pallid Cuckoo White-bellied Cuckoo-shrike Crimson Rosella Peaceful Dove White-browed Babbler Diamond Firetail Peregrine Falcon White-browed Scrubwren Dollarbird Pied Butcherbird White-eared Honeyeater Dusky Woodswallow Pied Currawong White-fronted Chat Eastern Rosella Rainbow Bee-eater White-naped Honeyeater Eastern Spinebill Red Wattlebird White-plumed Honeyeater Eastern Yellow Robin Red-browed Finch White-throated -

Surveys of the Barking Owl and Masked Owl on The

SUEYS O E AKIG OW A MASKE OW O E OWES SOES O EW SOU WAES S. J. S. DEBUS Division of Zoology, University of New England, Armidale, New South Wales 2351 Received: 4 March 2000 ld rv f th rn Ol nx nnvn nd Md Ol Tyto nvhllnd r ndtd t 4 t (0 rv plnt n th rtht Slp nd djnn trn prt f th rthrn bllnd f Sth Wl, t nvtt thr tt n rnnt vttn n pbl nd prvt lnd. h rv r ndtd vr thr r, fr t 8, n plb f th l, ll. h rn Ol rrdd t fr rv pnt (4% nd th Md Ol t n r pbl t pnt (2%, th n ddtnl, ndntl rrd f h p. th l p rrd n lr hbtt rnnt n pbl lnd, nd th rn Ol l rrd n t lr, hlth dlnd rnnt n prvt lnd. On brdn plr f rn Ol ntrd vr thr r, drn hh th rrd frt thr, thn n, fldln bfr n dlt dd drn th nxt (nfl brdn n. h pr rdnt, nd dfndd th nt r thrht th r. h pr brdn dt, dtrnd fr nl f pllt nd pr rn, ntd f 2 pr nt l, 26 pr nt brd nd 62 pr nt nt b nbr, nd 4 pr nt l, pr nt brd nd pr nt nt b b, nd thr nnbrdn dt ntd f 2 pr nt l, 2 pr nt brd nd 6 pr nt nt b nbr, nd 8 pr nt l, pr nt brd nd pr nt nt b b. -

North Head Site Story

Overview of North Head North Head, a tied island formed approximately 90 million years ago, is the northern headland at the entrance to Sydney Harbour. Derived from Hawkesbury Sandstone and Newport formations, the headland is comprised of predominantly sandstone and shale, which support a mosaic of different vegetation types. This land is managed by National Parks and Wildlife Service, Sydney Harbour Federation Trust, Q Station, The Australian Institute of Police Management and the North Head Sewerage Treatment Plant, Northern Beaches Council and others. North Head is a national heritage site. Banksia aemula, a characteristic species of Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub (ESBS), with Leptospermum laevigatum dominated senescent Flora at North Head ESBS in the background. North Head is dominated by dense sclerophyllous vegetation, which comprises eight distinct bentwing bat (Miniopterus schreibersii oceanensis).Two vegetation communities, including Coastal notable, and somewhat iconic, species that occur Sandstone Plateau Heath, Coastal Rock-plate at North Head are the long-nosed bandicoot Heath, Coastal Sandstone Ridgetop Woodland and (Perameles nasuta) and the little penguin the endangered Eastern Suburbs Banksia Scrub (Eudyptula minor), with both listed as threatened (ESBS). Characteristic species of plants within populations. these communities include the smooth-barked Several major threats to both flora and fauna occur apple (Angophora costata), red bloodwood (Corymbia at North Head. These include predation by gummifera), coastal tea tree (Leptospermum laevigatum), domestic and feral animals, vehicle strike heath-leaved banksia (Banksia ericifolia) and the (particularly bandicoots), fragmentation and loss of coastal banksia (Banksia integrifolia). A total of more habitat, weed infestation, inappropriate fire than 460 plant species have been recorded within regimes and stormwater runoff (increasing these communities so far, including the sunshine nutrients and the spread of weeds). -

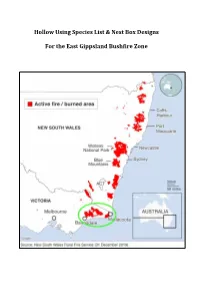

Hollow Using Species List & Nest Box Designs for the East Gippsland

Hollow Using Species List & Nest Box Designs For the East Gippsland Bushfire Zone Purpose of this booklet Large areas of native forest have been burnt by bushfires during the 2019-20 bushfire season, from farm to coast across the Great Dividing Range. And the fires are burning still as I write this today on the 4th of January 2020. Millions of native animals have perished – from insects, lizards, birds, frogs, to mammals. For these huge ‘armageddon’ bushfire impacted regions to be recolonised, nearby populations of native wildlife will need to survive and thrive. There are over 300 native species in Australia using tree hollows for shelter and breeding, of which 114 species are birds, and 83 of these species are mammals. There will have been a significant loss of old hollow-bearing trees throughout the burnt zones. It is expected that some birds may have escaped the flames, but will be unable to breed in future years if they require tree hollows for nesting. Surviving nocturnal arboreal mammals will similarly struggle to find tree hollows to shelter in during the day. This booklet series has been compiled from existing online resources to enable volunteer nest box makers to quickly learn how to make nest boxes, for the species that occur within their region. I have collated the information in this booklet from the following organisations and resources: Birdlife Australia: https://birdlife.org.au/images/uploads/education_sheets/INFO- Nestbox-technical.pdf Birds in Backyards: http://www.birdsinbackyards.net/Nest-Box-Plans Greater Sydney