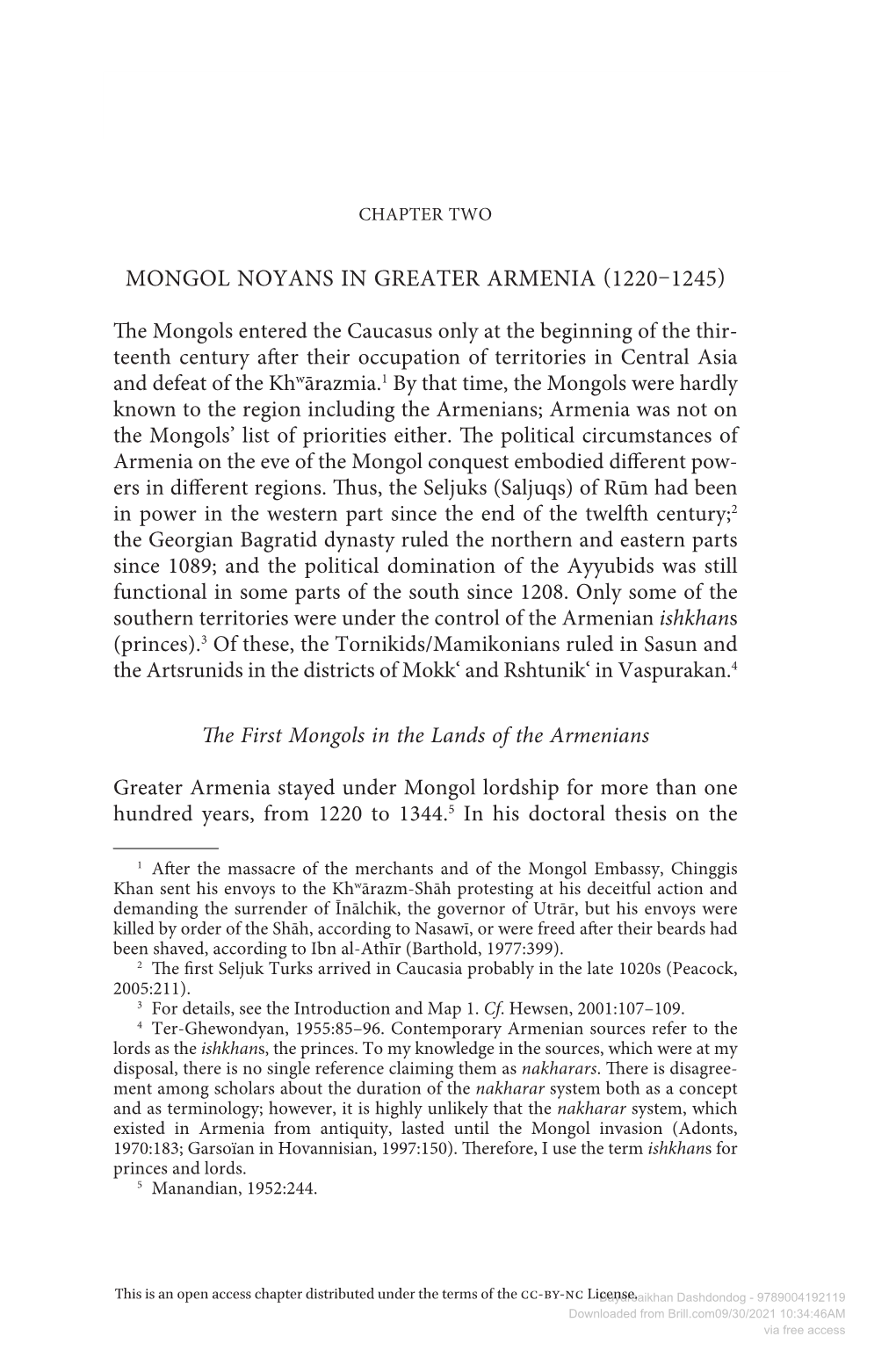

Mongol Noyans in Greater Armenia 1220 1245

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inscriptions. Nevertheless, the Mongols Had a Language and Character of Their Own, and This Appears at Intervals Upon Their Coins

00087560 BOMBAY BRANCH OF THU ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY, )fi TOWN HALL, BOMBAY. Ss :4 Digitized with financial assistance from the Government of Maharashtra on 18 July, 2018 CATALOGUE ORIENTAL COINS IN THE BRITfSH iMUSEUM. VOL. VI. LONDON: PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES. Longmans & Co., Paternoster Row ; B. M. P ickering , 66, Haymarket ; B. Quaritch, 15, Piccadilly ; A. A sher & Co.> 13, Bedford Street, Covent Garden, and at Berlin; TrubneR & Co, 57 & 59 L ddgate Hill. Paris : MM. C. Rollin & Feuardent , 4, Rue de Louvois . 1881. LONDON : GILBERT AND RIVINGTON, ST. J o h n ’s sq u a r e , clerkenwkll . 00087560 00087560 THE COINS OF THE MONGOLS IN THB^ BRITISH MUSEUM. CLASSES XVIII.—XXII. BY STANLEY LANE-POOLE. ed ite d by REGINALD STUART POOLE, CORRESPONDENT OF THE INSTITUTE OP FRANCE. LONDON PRINTED BY ORDER OF THE TRUSTEES. i88i. EDITOB’S PREFACE. T h is Sixth Volume of the Catalogue of Oriental Coins in the British Museum deals with the money issued by the Mongol Dynasties descended from Jingis Khan, correspond ing to Praehn’s Classes XVIII.—XXII. The only line of Khans tracing their lineage to Jingis excluded from this Yolume is that of Sheyban or Abu-l*KhOyr, which Was of late foundation and rose on the ruins of the Timurian empire. Timur’s own coinage, with that of his house, is reserved for the next (or Seventh) Volume, since he was not a lineal descendant of Jingis. On the other hand, the issues of the small dynasties which divided Persia among them between the decay of the Ilkhans and the invasion of Timur are included in this volume as a species of appendix. -

The Mongols in the West

Historical Site of Mirhadi Hoseini http://m-hosseini.ir ……………………………………………………………………………………… The Mongols in the West By Denis Sinor Denis Sinor Distinguished Professor Emeritus Department of Central Eurasian Studies, Indiana University, Bloomington Born in Hungary in 1916, Sinor was educated in Hungary, and Switzerland. As a student at the University of Budapest he received various fellowships. In France between 1939 and 1948, he held various teaching and research assignments. A member of the French Resistance, he joined the Free French Forces, served in the French occupation of Germany and was demobilized in November 1945. From 1948 to 1962 he was on the Faculty of Oriental Studies at Cambridge University, England. In 1962 he moved to IU, and 1963-1981 was Chairman of the Department of Uralic and Altaic Studies which he created. From 1965 to 1967 he was Chairman of the Asian Studies Program. In 1967 he founded the Asian Studies Research Institute, to become the Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, which he directed until 1981. In 2006 it was renamed Denis Sinor Institute for Inner Asian Studies. 1963-1988 he was Director of the Inner Asian and Uralic National Resource Center, the only one of its kind in the country. Indiana University honored him in 1986 with the "Rocking Chair Award" and the Thomas Hart Benton Mural Medallion, the John W. Ryan Award (2006) and inclusion into the "President's Circle" (2005). He has received two Guggenheim Fellowships (1968, 1981), and grants from the Rockefeller Foundation, the ACLS, the NEH, and IREX. In 1975 he was scholar-in-residence at the Rockefeller Fund Study Center, Villa Serbelloni, Bellagio. -

General Index

GENERAL INDEX Abaya, Mongol tribe, 345, 351, 360 archery, Abaqa 175-211 passim, 270 of medieval nomads, 135-36, 138, Abatai 187, 192, 196, 209 149, 151, 152 'Abbasids, 266, 278 Mamluk, 255 Abishqa, Mongol officer, 251 Mongol, 224, 233, 247, 249, 254-57 Abu 'I-Fida', Ayyubid prince and passim historian (d. 1331), 227-29 Turkish, 38, 40, 41, 63, 64, 82 Abu Bakr, 270 Arghun Aqa, 189, 192, 195, 196 Abuge, 270 ArighBoke, 178,180,181 Abulustayn, battle of (1276), 223-7 Armenians, 223 passim, 254, 258 Armenian church, 142 Acha (d. 1285), 315-20, 325 Armenian sources, 142 Acre, 202 Armor, 78, 143, 145, 149, 150, 161 Afghanistan, 175, 187, 260, 278 of horses, 149, 265-66 Ailu (d. 1287), 313-14, 317-20, 327 of Sui cavalry, 60-61 Akatirs, 110 of Turks, 40 Aksu, 388 Arni, 375, 392 'Ala al-Dfn, 270 'arradah, "counterweighted catapult", 268 Alans, 108, 109, 113, 127, 144, 147, arrows, 265, 280 incendiary, 279-80 Alaowading, 270 poisoned, 151 Alaqcot, Mongol tribe, 355 types of, 149-50 Aleppo, 226, 230, 239, 240, 270 arrow-makers, 266 Alghu (Chagadaid Khan) 180, 181, artisans, 266, 271, 277-79, 285 182, 200 Ascalon, town in modern Israel, 227 Ali, 319, 325 Ashide, 41 Alihaya, 318, 320 Ashina (Asina) 41, 43, 48, 111 Almaliq, 182, 203 Ashina She'er 42, 56 Altai, 180 asylmp 76, 77, 78, 80, 81, 82, 96 Ambughai, 277, 278 Atil (Itil), 115, 143 Ambush, 119, 134, 136 Attila, I 09, 110, 112, 125, 133, 138, Amiot, 428-30, 436 146, 153 Amfrzadah Sa!almish, Mongol Auxiliary forces 190, 191, 207, 208 commander, 242, 243 Avars, I 10, 112-13, 124, 126-28, Amu Darya, 279 133-34, 136-37, 146-47, 149-52, Amursana (d. -

News from Ancient Afghanistan.....5 Rather Than Attempt to Comment Part of an Elite but Non-Royal • Prof

Volume 4 Number 2 Winter 2006-2007 “The Bridge between Eastern and Western Cultures” In This Issue From the Editor • News from ancient Afghanistan.....5 Rather than attempt to comment part of an elite but non-royal • Prof. Tarzi’s 2006 excavations at here on every article in this issue residence? What is depicted? Is Bamiyan ..............................10 of our journal, let me share with the whole iconography connected • A visit to the region of historic you some thoughts inspired by with celebration of Nauruz? Is it Balkh.................................. 27 reading two important new books abstract and symbolic or rather • A new interpretation of the Afrasiab which are closely related to certain related to a very specific political murals.................................32 of our contributions. In the first situation? Is the Chinese scene on • Mapping Buddhist sites in Western volume, Royal Nauruz in the north wall a specific depiction Tibet ...................................43 Samarkand, the eminent scholar of court culture in China or simply • Han lacquerware in Xiongnu Prof. Frantz Grenet begins his emblematic of a Chinese prin- graves..................................48 essay with the statement: ‘A cess’s having been sent off as a • Ming-Timurid relations as recorded positive side to the so-called bride to Central Asia? It is certainly in Chinese sources ................54 ‘Ambassador’s painting’ at interesting that at least one • Hunting hounds along the Silk Samarkand is that we shall never contributor (Markus Mode) Road....................................60 fully understand it…This means explicitly disagrees with the • An interview with Kyrgyz epic that research on this painting will premise about Nauruz which is singers.................................65 never stop and this is excellent embodied in the volume’s title. -

Die Türken Mittler Kultureller Und Sprachlicher Strömungen in Eurasien

GERHARD DOERFER (1920-2003) Die Türken Mittler kultureller und sprachlicher Strömungen in Eurasien (Aus: bustan. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Kultur, Politik und Wirtschaft (Wien). 7. Jahrgang, Heft 2-3 [1966], S. 24a-32b) Vorliegender Artikel ist von J.P. Laut leicht überarbeitet und korrigiert worden, insb. bei bibliographischen Angaben. Korrek- turen und größere Zusätze stehen in [ ], ebenso die Seitenzahlen des Originals. Für Hinweise zum Chinesischen bzw. Lappi- schen danke ich Prof. Dr. Axel Schneider und Prof. Dr. Eberhard Winkler (beide Göttingen). [S. 24a] Die Urheimat1 der Türken liegt im zentralen Asien, in der heutigen Mongolei, aus der sie erst seit dem 10. Jahrhundert nach und nach in einem Jahrhunderte währenden Prozeß durch mongolische Stämme vertrieben wurden. Jedoch hat sich das alttürkische Reich des 6. Jahrhunderts bis fast nach Europa hin erstreckt, haben anderseits türkische Völker, wie die Toba, über weite Gebiete Chinas regiert, so daß der Herrschafts- und teilweise auch der Le- bensraum der Türken sich über ein ungeheures Territorium ausdehnte, das wegen seiner zen- tralen Lage die Türken zu idealen Mittlern zwischen der ostasiatischen Welt, vor allem China, und dem Westen, d. h. den iranischen, aber auch den slawischen Gebieten, prädestinierte. Spä- ter haben sich dann einzelne türkische Stämme losgelöst; so haben schließlich die Osmanen lange Zeit nicht nur über Anatolien, sondern auch über den Balkan und Arabien geherrscht, Azerbaidjaner und Türkmenen über Iran usw. Das heutige Siedlungsgebiet der Türken reicht etwa von Bosnien bis Westchina und vom Nördlichen Eismeer bis Südpersien. Das alles konnte nicht ohne weitreichende Wirkungen auf die Nachbarvölker bleiben; hierfür sollen die folgen- den Ausführungen einige typische Beispiele geben. -

Eski Türklerde Kültür Ve Sanat

ESKİ TÜRKLERDE KÜLTÜR VE SANAT İçindekiler Tablosu Giriş ....................................................................................................................... 3 Eski Türk Yurdundaki İlk Kültürler .......................................................................... 5 Tabiat ve İnsan ....................................................................................................... 8 Hunların Tarihi ..................................................................................................... 10 Yaşayışları ve Genel Kültürleri .............................................................................. 19 Esik Kurganı ......................................................................................................... 30 Din ve Sanat ......................................................................................................... 35 Arkeolojik Kazılar ................................................................................................. 45 Önemli Kurganlar Serisi ........................................................................................ 47 Buluntular ............................................................................................................ 50 Orta Asya’da Hayvan Üslubunun Doğuşu ............................................................. 52 Hunlarda Hayvan Üslubu ...................................................................................... 55 İlk Türk Halısı ve Türklerde Halıcılığın Gelişmesi .................................................. -

Mongol Imperialism in the Southeast : Uriyangqadai (1201-1272) and Aju (1127-1287)

Mongol imperialism in the southeast : Uriyangqadai (1201-1272) and Aju (1127-1287) Autor(en): Fiaschetti, Francesca Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Asiatische Studien : Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft = Études asiatiques : revue de la Société Suisse-Asie Band (Jahr): 71 (2017) Heft 4 PDF erstellt am: 05.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-737966 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch DE GRUYTER ASIA 2017; 71(A); 1119-1135 Francesca Fiaschetti* Mongol Imperialism in the Southeast: Uriyangqadai (1201-1272) and Aju (1127-1287) https://doi.org/10.1515/asia-2017-0008 Abstract: Son of the famous general Sübe'edei, Uriyanqadai followed in his father's footsteps into the highest ranks of the Mongol military. -

Khazaria Empire Could Not Extend Any Further South Because the Tatars and Turkmen Proved to Be About As Obstinate As the Afghans Have Been Throughout History

Our Advertisers Represent Some Of The Most Unique Products & Services On Earth! By Karl Schwarz 8-18-8 The Bush-Zionist Global War on Terror has taken another massive hit. Pakistan President Pervez Musharraf resigned at 10am CET - 4am in Washington, DC. Americans can now be assured that there will be NO Trans-Afghanistan Pipeline as TAP, or the alternative version of TAPI (Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India) until the United States completely changes its policies towards the people of Islam. Over recent months, the Taliban have grown in strength and most of Afghanistan is now under their control. It took a long time for this Bush Dirty Diaper to fill up, but folks, it is now an extremely nasty one. Some of the British journalists are doing a very good job in analyzing this latest US imperial expansion fiasco in Georgia. Guardian journalist Seumas Milne has done a fine job of presenting this matter in his August 14 article. http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2008/aug/14/russia.georgia What the world just witnessed in Georgia is more US imperialism than it is Russian aggression, just as Iraq and Afghanistan are about US and Zionist Imperialism and aggression. The truth will slowly surface in the coming months that Russia acted appropriately to defend against the ethic genocide of Russian Orthodox Christians by Muslims, Zionist Israelis, mercenaries and all dreamed up and sponsored by our pretend-Christian war criminal president. Bush and Rice: "Russia must remove its troops from Georgia!' No, our war criminal president must be removed from power in Washington DC. -

Dream Cleansers, from Tangut Inn

Perspectives Dream Cleansers, from Tangut Inn Luo Yijun Translation by Pingta Ku* This seems to be supported by information that the Khazar envoy ended his life at the court of some caliph by turning his soul inside out and slipping it on like an inverted glove. His torn skin, tanned and bound like a big atlas, held a place of honor in the caliph’s palace in Samarra. According to a second group of sources, the envoy had many a nasty moment. First, while still in Constantinople, he had to let his hand be cut off, because an influential man at the Greek court had paid in solid gold for the second large Khazar year, written on the envoy’s left palm. A third group of sources. He lived—The Khazar Dictionary tells us—like a living encyclopaedia of the Khazars, on money earned by standing quietly through the long nights. He would keep vigil, his gaze fixed on the Bosporus’ silver treetops, which resembled puffs of smoke. While he stood, Greek and other scribes would copy the Khazar history from his back and thighs into their books. It is said that . the letters of the Khazar alphabet derived their names from foods, the numbers from the names of the seven types of salt the Khazars differentiated. One of his sayings has been preserved. It reads: “If the Kahzars did better in Itil they would do better in Constantinople too.” Gener- ally speaking, he said many things that were contrary to what was written on his skin. —Milorad Pavic, Dictionary of the Khazars Editor’s Note: Xixia luguan (Tangut Inn), a two-volume novel by Taiwanese writer Luo Yijun (a.k.a. -

Great Personalities in the History of the Black Sea During the Middle Ages: the Case of Genghis Khan

Great personalities in the history of the Black Sea during the Middle Ages: the case of Genghis Khan Balasa Argyroula SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea Cultural Studies January 2016 Thessaloniki-Greece 1 Student Name: Balasa Argyroula SID: 2201130005 Supervisor: Prof. Eleni Tounta Examiner A: Dr. Giannis Smarnakis Examiner B: Dr. Dimitrios Kontogeorgis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. © January 2016, Argyroula Balasa, 2201130005 No part of this dissertation may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without the author’s prior permission. January 2016 Thessaloniki-Greece 2 Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea Cultural Studies at the International Hellenic University. Genghis Khan was one of the most interesting personalities who went through the Black Sea area during the Middle Ages. The aim of this dissertation is to provide a detailed presentation and description of Genghis Khan, one of the most significant people in History and one of the most influential figures of all time. The main core of this thesis is the investigation of this unique personality who managed to change Asia and Europe, through his campaigns. The core of the present inquiry contains a description of the main sources about the Mongols, how the Mongol society was before Genghis Khan and the daily life of the nomadic tribes in Asia. Information about Genghis Khan’s efforts to rise and become a leader (khan) as well as the way he managed to organize the new Empire, are also provided. -

The Ya'juj and the Ma'juj (Gog and Magog)

The Ya'juj and The Ma'juj (Gog and Magog) Abu Muhammad Contents Page Understanding the issue of The Ya'jooj and The Ma'jooj ....................................................... 3 A clarification ............................................................................................................................ 4 Dhul-Qarnein .......................................................................................................................... 10 Who was Dhul-Qarnein ...................................................................................................... 12 An interesting theory regarding Ya'juj and Ma'juj ............................................................. 21 The History of the Banu Israel during the era of Cyrus ...................................................... 22 The dream of Nabi Danyaal (Alaihi Salaam) regarding Cyrus ............................................ 24 Cyrus's conquest - towards Lydia (in the West) ................................................................. 30 Cyrus's journey towards the East (To the far East of the Caspian Sea- passing Sogdiana) 31 The Conquest of Babylon ................................................................................................... 34 RELIGION OF CYRUS ........................................................................................................... 36 Ancient Iranian Religion ..................................................................................................... 38 Iran and the Religion of Ibrahim Zardasht......................................................................... -

Some Early Inner Asian Terms Related to the Imperial Family and the Comitatus Christopher P

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarlyCommons@Penn University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and School of Arts and Sciences Civilizations 2013 Some Early Inner Asian Terms Related to the Imperial Family and the Comitatus Christopher P. Atwood University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the East Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Atwood, Christopher P., "Some Early Inner Asian Terms Related to the Imperial Family and the Comitatus" (2013). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 14. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/14 At the time of publication, author Christopher P. Atwood was affiliated with Indiana University. Currently, he is a faculty member in the East Asian Languages and Civilizations Department at the University of Pennsylvania. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/14 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Early Inner Asian Terms Related to the Imperial Family and the Comitatus Disciplines Arts and Humanities | East Asian Languages and Societies Comments At the time of publication, author Christopher P. Atwood was affiliated with Indiana University. Currently, he is a faculty member in the East Asian Languages and Civilizations Department at the University of Pennsylvania. This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/14 Some Early Inner Asian Terms Related to the Imperial Family and the Comitatus By Christopher P. Atwood (Indiana University) Introduction1 Chinese histories preserve a vast number of terms, names, and titles dating from the Türk era (roughly 550–750) and before.