Study Notes Advent of Divine Justice.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acquiring Virtues and Developing Character?

Becoming A Brilliant Star Character Development Why Should We Acquire Virtues And Develop Our Character? The Purpose And Aim Of The Manifestation Of God Is Character Development 1. The purpose of the one true God in manifesting Himself is to summon all mankind to truthfulness and sincerity, to piety and trustworthiness, to resignation and submissiveness to the Will of God, to forbearance and kindliness, to uprightness and wisdom. His object is to array every man with the mantle of a saintly character, and to adorn him with the ornament of holy and goodly deeds. Bahá'u'lláh: Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u’lláh, p. 299 2. The aim of this Wronged One in sustaining woes and tribulations, in revealing the Holy Verses and in demonstrating proofs hath been naught but to quench the flame of hate and enmity, that the horizon of the hearts of men may be illumined with the light of concord and attain real peace and tranquillity. From the dawning-place of the divine Tablet the day-star of this utterance shineth resplendent, and it behoveth everyone to fix his gaze upon it: We exhort you, O peoples of the world, to observe that which will elevate your station. Hold fast to the fear of God and firmly adhere to what is right. Verily I say, the tongue is for mentioning what is good, defile it not with unseemly talk. God hath forgiven what is past. Henceforward everyone should utter that which is meet and seemly, and should refrain from slander, abuse and whatever causeth sadness in men. -

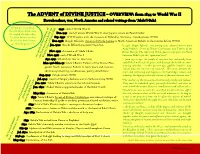

The ADVENT of DIVINE JUSTICE – OVERVIEW: from 1844 to World War II

The ADVENT of DIVINE JUSTICE – OVERVIEW: from 1844 to World War II Dawnbreakers, war, North America and related writings from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá for groups, read aloud: 1945: end of World War II the title block above, then the angled Dawnbreakers Dec. 1941: the US enters World War II after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor line from bottom up, then Sep. 1939: WWII begins with the invasion of Poland by Germany, Canada enters WWII the timeline from bottom Dec. 1938: Shoghi Effendi’s Advent of Divine Justice to North American Bahá’ís in the months before WWII up, then the green text Jan. 1922: Shoghi Effendi appointed Guardian In 1938, Shoghi Effendi, anticipating war, adapted themes from ‘Abdu’l–Bahá’s Secret of Divine Civilization and Tablets of the Nov. 1921: Ascension of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Divine Plan for The Advent of Divine Justice to prepare the North Nov. 1918: end of World War I American Bahá’ís for the “appointed time”. Apr. 1917: US declares war on Germany “…from age to age, the temple of existence has continually been Mar. 1916–Mar. 17: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Tablets of the Divine Plan embellished with a fresh grace, and distinguished with an ever- varying splendor… in this present age, godlike impulses may guides North American Bahá’ís to teach peace and oneness; radiate from the conscience of mankind… We must…promote the advocates pioneering, steadfastness, purity, detachment peace and well-being and happiness, the knowledge, culture and Aug. 1914: Canada enters WWI industry, the dignity, value and station, of the entire human race.” Jul. -

The Importance of Deepening Our Knowledge and Understanding Of

The Importance of Deepening our Knowledge and Understanding of the Faith The Importance of Deepening our Knowledge and Understanding of the Faith A compilation of extracts from the Bahá'í Writings Prepared by the Research Department of the Universal House of Justice Bahá'í World Centre Baha'i Publishing Trust, Wilmette, Illinois 60091 Copyright by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of Canada 1983 Also in the Compilation of Compilations Vol. I, pp. 187-234 CONTENTS Extracts from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh Extracts from the Writings of `Abdu'l-Bahá Extracts from the Utterances of `Abdu'l-Bahá Extracts from Letters written by Shoghi Effendi Extracts from Letters written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi Extracts from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh 1. Recite ye the verses of God every morn and eventide. Whoso faileth to recite them hath not been faithful to the Covenant of God and His Testament, and whoso turneth away from these holy verses in this Day is of those who throughout eternity have turned away from God. Fear ye God, O My servants, one and all. Bahá'u'lláh, The Kitab-i-Aqdas, p. 73 2. Were any man to taste the sweetness of the words which the lips of the All-Merciful have willed to utter, he would, though the treasures of the earth be in his possession, renounce them one and all, that he might vindicate the truth of even one of His commandments, shining above the Dayspring of His bountiful care and loving-kindness. Bahá'u'lláh, A Synopsis and Codification of the Laws and Ordinances of Kitab-i-Aqdas, p. -

Religion Asserts That Its Central Concerns Are Discovering Truth and Implementing the Measures Called for by That Truth

1 Truth: A Path for the Skeptic 2 Truth: A Path for the Skeptic Robert Vail Harris, Jr. First Edition (PDF Version) Copyright 2018 Robert Vail Harris, Jr. Website: truth4skeptic.org Email: [email protected] What is truth? Is there meaning in existence? What are life and death? These and similar questions are explored here. This work draws on techniques and examples from science and mathematics in a search for insights from ancient and modern sources. It is writ- ten especially for the skeptical scientist, the agnostic, and the athe- ist. It is informal but rigorous, and invites careful reflection. 3 Contents Page Questions 4 Answers 84 Actions 156 Notes and References 173 Truth: A Path for the Skeptic 4 Questions Overview The search for truth is a lifelong endeavor. From the time we open our eyes at birth until we close them at the hour of death, we are sorting and sifting, trying to determine what is true and what is not, what is reality and what is illusion, what is predictable and what is random. Our understanding of truth underpins our priorities and all our activities. Every thought we have, every step we take, every choice we make is based on our assessment of what is true. Knowing the truth enriches our lives, while false beliefs impover- ish and endanger us. The importance of truth can be illustrated by countless exam- ples. Contractual arrangements are accompanied by an assertion of truthfulness. Participants in a trial are required to tell the truth. Various implements have been used to try to ascertain truth, from the dunking and burning of accused witches to the use of lie detec- tors. -

Compilation of Bahá'í Sacred Writings on the Oneness of Humanity and The

Compilation of Bahá’í sacred writings on the oneness of humanity and the process of achieving unity Abridged from The Power of Unity: Overcoming Racial Divisions, Rebuilding America Compiled by Bonnie Taylor Copyright © 2019 by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States Print and ebook editions of the full compilation are available at https://www.bahaibookstore.com/Power-of-Unity-New-Edition-P9588.aspx Contents ONENESS: OUR HUMAN REALITY One Human Species p. 2 The Divine Criterion for the Measurement of Humanity p. 2 Humanity’s Common Bonds p. 4 SPIRITUAL TRANSFORMATION Unity—The Commandment p. 5 Love—The Source of Unity p. 6 Religion—The Perfect Means for Engendering Unity p. 7 Understanding the Bases of Prejudices and Disunity p. 9 Abolishing Prejudices and Racism p. 10 Averting the Dangers of Disunity, Prejudice, and Racism p. 13 Avoiding Strife and Overcoming Estrangement p. 14 Appreciating the Diversity of the Human Family p. 16 The Necessity of Courage and Wisdom p. 17 SERVICE FOR SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION Promoting Harmony and Unity p. 18 The Requirements for Teaching p. 19 Teaching Diverse Populations p. 20 Upholding Justice: A Prerequisite to Unity p. 22 Safeguarding the Rights and Privileges of Minority Groups p. 24 Combating the Negative Forces in our Society p. 24 THE PROMISE OF THE FUTURE The Destiny of America p. 26 Global Unity and Peace p. 28 1 O ne Human Species O CHILDREN OF MEN! Know ye not why We created you all from the same dust? That no one should exalt himself over the other. -

The Eternal Quest for God: an Introduction to the Divine Philosophy of `Abdu'l-Bahá Julio Savi

The Eternal Quest for God: An Introduction to the Divine Philosophy of `Abdu'l-Bahá Julio Savi George Ronald, Publisher 46 High Street, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 2DN Copyright © Julio Savi, 1989 All rights Reserved British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Savi, Julio The eternal quest for God: an introduction to the divine philosophy of `Abdu'l-Bahá. I. Bahaism. Abd al Baha ibn Baha All ah, 1844-1921. I. Title II. Nell'universo sulle tracce di Dio. English 297'.8963 ISBN 0-85398-295-3 Printed in Great Britain by Billing and Sons Ltd, Worcester By the same author Nell'universo sulle tracce di Dio (EDITRICE NÚR, ROME, 1988) Bahíyyih Khánum, Ancella di Bahá (CASA EDITRICE BAHÁ'Í, ROME, 1983) To my father Umberto Savi with love and gratitude I am especially grateful to Continental Counselor Dr. Leo Niederreiter without whose loving encouragement this book would have not been written Chapter 1 return to Table of Contents Notes and Acknowledgements Italics are used for all quotations from the Bahá'í Sacred Scriptures, namely `any part of the writings of the Báb, Bahá'u'lláh and the Master'. (Letter on behalf of Shoghi Effendi, in Seeking the Light of the Kingdom (comp.), p.17.) Italics are not used for recorded utterances by `Abdu'l- Bahá. Although very important for the concepts and the explanations they convey, when they have `in one form or the other obtained His sanction' (Shoghi Effendi, quoted in Principles of Bahá'í Administration, p.34) - as is the case, for example, with Some Answered Questions or The Promulgation of Universal Peace - they cannot `be considered Scripture'. -

Power-Divine-Assistance.Pdf

The Power of Divine Assistance Compiled by: The Research Department of the Universal House of Justice August 1981 Revised July 1990 From the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh Be not dismayed, O peoples of the world, when the day star of My beauty is set, and the heaven of My tabernacle is concealed from your eyes. Arise to further My Cause, and to exalt My Word amongst men. We are with you at all times, and shall strengthen you through the power of truth. We are truly almighty. Whoso hath recognized Me, will arise and serve Me with such determination that the powers of earth and heaven shall be unable to defeat his purpose. (“Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh”, rev. ed. (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1984), sec. 71, p. 137; “A Synopsis and Codification of the Kitáb-i-Aqdas, the Most Holy Book of Bahá’u’lláh”, 1st ed. (Haifa: Bahá’í World Centre, 1973), p. 14) [1] Let not your hearts be perturbed, O people, when the glory of My Presence is withdrawn, and the ocean of My utterance is stilled. In My presence amongst you there is a wisdom, and in My absence there is yet another, inscrutable to all but God, the Incomparable, the All-Knowing. Verily, We behold you from Our realm of glory, and shall aid whosoever will arise for the triumph of Our Cause with the hosts of the Concourse on high and a company of Our favoured angels. (“Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh”, sec. 72, p. -

Testimonial on the Love of God and Teaching

Testimonial on the Love of God and Teaching Compilation developed by Mehrdad Fazli College Station, Texas January, 1998 Handouts to accompany institute training program Page numbers refer to transparencies used in the training materials Materials authorized for use by the Research Department, National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá’ís of the United States Copyrighted materials have been omitted; permission is being sought to include them. 1. The essence of love is for man to turn his heart to the Beloved One, and sever himself from all else but Him, and desire naught save that which is the desire of his Lord. Bahá’u’lláh: Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh, p. 155 2a. The source of courage and power is the promotion of the Word of God, and steadfastness in His Love. Bahá’u’lláh: Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh, p. 156 2b. The essence of wealth is love for Me; whoso loveth Me is the possessor of all things, and he that loveth Me not is indeed of the poor and needy. This is that which the Finger of Glory and Splendour hath revealed. Bahá’u’lláh: Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh, p. 156 3a. O SON OF MAN! Veiled in My immemorial being and in the ancient eternity of My essence, I knew My love for thee; therefore I created thee, have engraved on thee Mine image and revealed to thee My beauty. Bahá’u’lláh: Hidden Words (Arabic), #3 3b. O SON OF MAN! I loved thy creation, hence I created thee. Wherefore, do thou love Me, that I may name thy name and fill thy soul with the spirit of life. -

The Baha'i Principle of Religious Unity and the Challenge of Radical Pluralism

v479 N S 6o49 THE BAHA'I PRINCIPLE OF RELIGIOUS UNITY AND THE CHALLENGE OF RADICAL PLURALISM THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts By Dann J. May, B.S, M.S. Denton, Texas December, 1993 May, Dann J., The Baha'i Principle of Religious Unity and the Challenge of Radical Pluralism. Master of Arts (Interdisciplinary Studies), December 1993, 103 pp., bibliography, 141 titles. The Baha'i principle of religious unity is unique among the world's religious traditions in that its primary basis is found within its own sacred texts and not in commentaries of those texts. The Bahs'i principle affirms the exis- tence of a common transcendent source from which the religions of the world originate and receive their inspiration. The Bahe'i writings also emphasize the process of personal transformation brought about through faith as a unifying factor in all religious traditions. The apparent differences between the world's religious traditions are explained by appealing to a perspectivist approach grounded in a process metaphysics. For this reason, I have characterized the Baha'i view as "process perspectivism". Radical pluralism is the greatest philo- sophical challenge to the Bahs'i principle of religious unity. The main criticisms made by the radical pluralists are briefly examined. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to Dr. George James of the University of North Texas for not only supporting my thesis and for his encouragement and helpful advice, but also for his friendship and help in guiding my career change from geology to philosophy. -

Extracts from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh

Extracts from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh and ‘Abdu’l-Bahá and from the Letters of Shoghi Effendi and the Universal House of Justice on Scholarship Prepared by the Research Department of the Universal House of Justice February 1995 Extracts 1. The Station of Scholarship 1 – 20 1.1 Importance of Knowledge and Learning 1 – 6 1.2 Characteristics of the “truly learned” 4 – 13 1.3 Scope of “Bahá’í Scholarship” 14 1.4 Appreciation of Scholarship 15 – 20 2. Functions of Bahá’í Scholarship 21 – 41 2.1 Promotion of Human Welfare 21 – 25 2.2 Defence of the Faith 26 – 29 2.3 Expansion and Consolidation of the Bahá’í Community 30 – 35 2.4 Contribution to Scholarly Development 36 – 41 3. General Principles and Guidelines 42 – 78 3.1 Spiritual Foundation 42 – 50 3.2 “Useful” Sciences 51 – 55 3.3 Attitudes of the Scholar 56 – 64 3.4 Methodological Issues 65 – 71 3.5 The Covenant 72 –78 1. The Station of Scholarship 1.1 Importance of Knowledge and Learning From the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh Knowledge is one of the wondrous gifts of God. It is incumbent upon everyone to acquire it. Such arts and material means as are now manifest have been achieved by virtue of His knowledge and wisdom which have been revealed in Epistles and Tablets through His Most Exalted Pen—a Pen out of whose treasury pearls of wisdom and utterance and the arts and crafts of the world are brought to light. (“Tablets of Bahá’u’lláh Revealed after the Kitáb-i-Aqdas” (Wilmette: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1988), p. -

Human Knowledge and the Advancement of Society

Human Knowledge and the Advancement of Society HODA MAHMOUDI Music is the one incorporeal entrance into the higher world of knowledge which compre- hends mankind but which mankind cannot comprehend. ——Ludwig van Beethoven Abstract Human knowledge is the means toward realizing a global civilization as envis- aged by Bahá’u’lláh. This paper examines the concept of knowledge and its treat- ment in the Bahá’í texts followed by an exploration of certain themes specified in the current Five Year Plan as brought forward and promulgated by the Universal House of Justice. These themes focus the worldwide Bahá’í communi- ty’s consultation, reflection, and its efforts towards actions which exercise knowledge in constructing a better world. The paper also explores the individ- ual’s adoption of an unassuming learning mode in response to applying acquired spiritual and secular knowledge to the complex and enduring process of civiliza- tion building. Résumé La connaissance humaine est le moyen par lequel une cilivisation mondiale, telle qu’envisagée par Bahá’u’lláh, pourra être réalisée. L’auteur examine le concept de la connaissance et ce qu’en disent les textes bahá’ís, puis il explore certains thèmes pré- cisés dans le plan de cinq ans actuel établi et promulgué par la Maison Universelle de Justice. C’est sur ces thèmes que se concentrent la consultation, la réflexion et les efforts de la communauté mondiale baha’ie en vue d’actions qui constituent une application de la connaissance pour établir un monde meilleur. L’auteur examine également l’adoption par l’individu d’un mode d’apprentissage humble qui découle de l’application des connaissances spirituelles et séculières à la démarche continue et complexe visant l’établissement d’une civilisation nouvelle. -

Youth Can Move the World

Youth Can Move the World Melanie Smith and Paul Lample Part of a Series on Major Themes of the Creative Word “The Word of God may be likened unto a sapling, whose roots have been implanted in the hearts of men. It is incumbent upon you to foster its growth through the living waters of wisdom, of sanctified and holy words, so that its root may become firmly fixed and its branches may spread out as high as the heavens and beyond.” —Bahá’u’lláh 1 In this series: The Word of God The Covenant: Its Meaning and Origin and Our Attitude Toward It The Significance of Bahá’u’lláh’s Revelation Youth Can Move the World The Spiritual Conquest of the Planet The Journey of the Soul Palabra Publications 7369 Westport Place West Palm Beach, Florida 33413. U.S.A. 1-561-697-9823 1-561-697-9815 (fax) [email protected] www.palabrapublications.com Copyright © 1991 by Palabra Publications. All right reserved. Published July 1991. Second printing April 1994. Electronic edition December 2005. Extracts from the following books were reprinted with the permission of George Ronald, Publisher: Honnold, Vignettes of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, 1982; Taherzadeh, The Revelation of Bahá’u’lláh, Volume III, 1983; and Vick, Social and Economic Development: A Bahá’í Approach, 1989. Cover photograph by David Smith. 2 Youth Can Move the World Contents Preface ii Foreword: a Message to Bahá’í Youth iv 1 The Battle of Darkness and Light 5 2 Disciplines of the Spiritual Warrior 15 3 Strengthening the Spirit 27 4 Praiseworthy Character 37 5 A Life of Service 49 6 Teaching 59 7 The Field of Action: Discourse 71 8 The Field of Action: Consecration 83 Index to the Role and Responsibilities of Youth 93 3 Preface A letter written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi states: “The principles, administration and fundamentals of the Faith are well known, but the friends need greatly to study the more profound works which would give them spiritual maturity to a greater degree, unify their community life, and enable them to better exemplify the Bahá’í way of living.