The Baha'i Principle of Religious Unity and the Challenge of Radical Pluralism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acquiring Virtues and Developing Character?

Becoming A Brilliant Star Character Development Why Should We Acquire Virtues And Develop Our Character? The Purpose And Aim Of The Manifestation Of God Is Character Development 1. The purpose of the one true God in manifesting Himself is to summon all mankind to truthfulness and sincerity, to piety and trustworthiness, to resignation and submissiveness to the Will of God, to forbearance and kindliness, to uprightness and wisdom. His object is to array every man with the mantle of a saintly character, and to adorn him with the ornament of holy and goodly deeds. Bahá'u'lláh: Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u’lláh, p. 299 2. The aim of this Wronged One in sustaining woes and tribulations, in revealing the Holy Verses and in demonstrating proofs hath been naught but to quench the flame of hate and enmity, that the horizon of the hearts of men may be illumined with the light of concord and attain real peace and tranquillity. From the dawning-place of the divine Tablet the day-star of this utterance shineth resplendent, and it behoveth everyone to fix his gaze upon it: We exhort you, O peoples of the world, to observe that which will elevate your station. Hold fast to the fear of God and firmly adhere to what is right. Verily I say, the tongue is for mentioning what is good, defile it not with unseemly talk. God hath forgiven what is past. Henceforward everyone should utter that which is meet and seemly, and should refrain from slander, abuse and whatever causeth sadness in men. -

Report Iran: the Situation of the Bahá'í Community

Report Iran: The situation of the Bahá’í community Report Iran: The situation of the Bahá’í community LANDINFO – 12 AUGUST 2016 1 About Landinfo’s reports The Norwegian Country of Origin Information Centre, Landinfo, is an independent body within the Norwegian Immigration Authorities. Landinfo provides country of origin information to the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (Utlendingsdirektoratet – UDI), the Immigration Appeals Board (Utlendingsnemnda – UNE) and the Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security. Reports produced by Landinfo are based on information from carefully selected sources. The information is researched and evaluated in accordance with common methodology for processing COI and Landinfo’s internal guidelines on source and information analysis. To ensure balanced reports, efforts are made to obtain information from a wide range of sources. Many of our reports draw on findings and interviews conducted on fact-finding missions. All sources used are referenced. Sources hesitant to provide information to be cited in a public report have retained anonymity. The reports do not provide exhaustive overviews of topics or themes, but cover aspects relevant for the processing of asylum and residency cases. Country of origin information presented in Landinfo’s reports does not contain policy recommendations nor does it reflect official Norwegian views. Translation provided by Cellule Relations internationales et européennes, Direction de l’immigration, Service Réfugiés, Luxembourg. © Landinfo 2017 The material in this report is covered by copyright law. Any reproduction or publication of this report or any extract thereof other than as permitted by current Norwegian copyright law requires the explicit written consent of Landinfo. For information on all of the reports published by Landinfo, please contact: Landinfo Country of Origin Information Centre Storgata 33A P.O. -

A Journey Through the Seven Valleys1 of Bahá'u'lláh

A Journey through t he Seven Valle ys A Journey through the Seven Valleys1 of Bahá’u’lláh by Ghasem Bayat Preamble n this brief journey through the Seven Va l l e y s2 of Bahá’u’lláh, we will partake of its spiritual bounties, focus on its principal message, tune our hearts to the teachings it enshrines, marvel at its masterful composition Iand form, and recognize some of the distinctive features of this book as compared with Islamic mystic writ- ings. This brief journey is at best an introduction to this Epistle, and is intended to encourage the readers to embark on an in-depth study of the Seven Valleys to receive the full measure of love and life it off e r s . The Historical Background This Epistle of Bahá’u’lláh was revealed during the Baghdad period, circa 1862 C .E. It was revealed in answer to questions raised by S ha yk h M u h y i ’ d - D í n ,3 the judge of K hániqayn, a town located in Iraqi Kurdistan, northeast of Baghdad, and near the Iranian border. The words of the beloved Guardian in describing the significance of this Epistle and its relation to other Writings of Bahá’u’lláh provides us with a perspective on this book: To these two outstanding contributions to the world’s religious literature [the Kitáb-i-ˆqán and the Hidden Words], occupying respectively, positions of unsurpassed preeminence among the doctrinal and ethical Writings of the Author of the Bahá’í Dispensation, was added, during that same period, a treatise that may well be regarded as His greatest mystical composition, designated as the “Seven Valleys,” -

Revelation & Social Reality

Revelation & Social Reality Learning to Translate What Is Written into Reality Paul Lample Palabra Publications Copyright © 2009 by Palabra Publications All rights reserved. Published March 2009. ISBN 978-1-890101-70-1 Palabra Publications 7369 Westport Place West Palm Beach, Florida 33413 U.S.A. 1-561-697-9823 1-561-697-9815 (fax) [email protected] www.palabrapublications.com Cover photograph: Ryan Lash O thou who longest for spiritual attributes, goodly deeds, and truthful and beneficial words! The outcome of these things is an upraised heaven, an outspread earth, rising suns, gleaming moons, scintillating stars, crystal fountains, flowing rivers, subtle atmospheres, sublime palaces, lofty trees, heavenly fruits, rich harvests, warbling birds, crimson leaves, and perfumed blossoms. Thus I say: “Have mercy, have mercy O my Lord, the All-Merciful, upon my blameworthy attributes, my wicked deeds, my unseemly acts, and my deceitful and injurious words!” For the outcome of these is realized in the contingent realm as hell and hellfire, and the infernal and fetid trees, as utter malevolence, loathsome things, sicknesses, misery, pollution, and war and destruction.1 —BAHÁ’U’LLÁH It is clear and evident, therefore, that the first bestowal of God is the Word, and its discoverer and recipient is the power of understanding. This Word is the foremost instructor in the school of existence and the revealer of Him Who is the Almighty. All that is seen is visible only through the light of its wisdom. All that is manifest is but a token -

Solace of the Heart’

Solace of the Heart Peter Mputle Revised Edition 2020 1 Dedicated to all those inquiring minds, for they are bound to tread a path of search and discover a hidden Treasure laid within a mystic cave of Eternity. 2 Contents Foreword 4 Section 1: Spirituality 1. Lifeless life 6 2. High Call 7 3. Secret of Ages 8 4. The Glory of God 9 5. Fearless Warrior 10 6. Crying Voice 11 7. Yearning 12 8. The Last Breath 12 9. Rest not in Peace 13 10. Synopsis 14 11. Arise 15 12. Chocolate of God 16 13. Chocolate Skin 16 14. Remarkable ‘One’ 17 15. A Thousand Years 18 16. Beware! 19 17. What...! 20 18. The Inseparable Two 21 19. Mortal Separation 21 20. The ‘WORD’ 22 21. Order 23 22. Embodiment of real Life 24 23. Bread of Heaven 25 24. The Sadratu’l Muntaha 26 25. Angel Gabriel 27 26. Triangular Love 28 27. Understanding 28 28. Divine Utterances 29 Section 2: Reflections on the ‘Seven Valleys’ 29. The Path of Search 30 30. The Valley of Love 31 31. Valley of Knowledge 32 32. Unity 33 33. Pure Contentment 34 34. Wonderment 35 35. True Poverty 36 Section 3: Temper 36. Lamentation of the Desolate 37 37. Forgotten Love 38 38. Diminishing Love 38 39. Drooping Heart 38 40. Layli 39 41. Lady Layli 40 42. Spurious Assumptions 41 43. Voices 41 References 42 3 Foreword The poems in this booklet were inspired by the Holy Writings of the Bahá’í Faith. The evidence of this is the type of language and words used which symbolises the Shakespearean era and the King James Version of Bible. -

Buddhism and the Bahá'í Writings: an Ontological Rapprochement

Buddhism and the Bahá’í Writings An Ontological Rapprochement * Ian Kluge Buddhism is one of the revelations recognised by the Bahá’í Faith as being divine in origin and, therefore, part of humankind’s heritage of guidance from God. This religion, which has approximately 379 million followers 1 is now making significant inroads into North America and Europe where Buddhist Centres are springing up in record numbers. Especially because of the charismatic leader of Tibetan Prasangika Buddhism, the Dalai Lama, Buddhism has achieved global prominence both for its spiritual wisdom as well as for its part in the struggle for an independent Tibet. Thus, for Bahá’ís there are four reasons to seek a deeper knowledge of Buddhism. In the first place, it is one of the former divine revelations and therefore, inherently interesting, and second, it is one of the ‘religions of our neighbours’ whom we seek to understand better. Third, a study of Buddhism also allows us to better understand Bahá’u’lláh’s teaching that all religions are essentially one. (PUP 175) Moreover, if we wish to engage in intelligent dialogue with them, we must have a solid understanding of their beliefs and how they relate to our own. We shall begin our study of Buddhism and the Bahá’í Writings at the ontological level because that is the most fundamental level at which it is possible to study anything. Ontology, which is a branch of metaphysics, 2 concerns itself with the subject of being and what it means ‘to be,’ and the way in which things are. -

Syllabus-Bahaullahs

Director: Dr. Robert H. Stockman www.wilmetteinstitute.org Email: [email protected] Voice: (877)-WILMETTE Course: ST131: Bahá'u'lláh's Revelation: A Systematic Survey Instructors: Robert Stockman: https://wilmetteinstitute.org/faculty_bios/robert-stockman/ Nima Rafiei: https://wilmetteinstitute.org/faculty_bios/nima-rafiei/ Course Description: The writings of Bahá'u'lláh (1817-92), prophet-founder of the Bahá'í Faith, is estimated to comprise 18,000 works and in excess of six million words, composed in Arabic, Persian, and a unique mixture of both. Approximately 5-7% has been translated into English, but the works available are the most important. In this course we will undertake a systematic introduction to twenty of Bahá'u'lláh’s most important works, ranging from the Rashḥ-i-‘Amá (1853) to Epistle to the Son of the Wolf (1892). We will study the works in chronological order of composition, examining the themes in the works, topics that Bahá'u'lláh progressively revealed during His ministry, and related tablets wherever possible. We will not read most of the twenty works in their entirety but will study significant passages and sections from them. The course will appeal to anyone seeking a deeper understanding of Bahá'u'lláh’s immense corpus. Learning Outcomes of Wilmette Institute courses relevant to this course: Knowledge: Demonstrate knowledge and interdisciplinary insights gained from the course and service learning. Abilities: Independently investigate to discern fact from conjecture. Engage in public discourse, consultation, service -

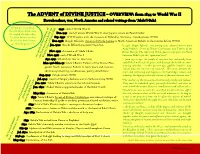

The ADVENT of DIVINE JUSTICE – OVERVIEW: from 1844 to World War II

The ADVENT of DIVINE JUSTICE – OVERVIEW: from 1844 to World War II Dawnbreakers, war, North America and related writings from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá for groups, read aloud: 1945: end of World War II the title block above, then the angled Dawnbreakers Dec. 1941: the US enters World War II after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor line from bottom up, then Sep. 1939: WWII begins with the invasion of Poland by Germany, Canada enters WWII the timeline from bottom Dec. 1938: Shoghi Effendi’s Advent of Divine Justice to North American Bahá’ís in the months before WWII up, then the green text Jan. 1922: Shoghi Effendi appointed Guardian In 1938, Shoghi Effendi, anticipating war, adapted themes from ‘Abdu’l–Bahá’s Secret of Divine Civilization and Tablets of the Nov. 1921: Ascension of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Divine Plan for The Advent of Divine Justice to prepare the North Nov. 1918: end of World War I American Bahá’ís for the “appointed time”. Apr. 1917: US declares war on Germany “…from age to age, the temple of existence has continually been Mar. 1916–Mar. 17: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Tablets of the Divine Plan embellished with a fresh grace, and distinguished with an ever- varying splendor… in this present age, godlike impulses may guides North American Bahá’ís to teach peace and oneness; radiate from the conscience of mankind… We must…promote the advocates pioneering, steadfastness, purity, detachment peace and well-being and happiness, the knowledge, culture and Aug. 1914: Canada enters WWI industry, the dignity, value and station, of the entire human race.” Jul. -

The Importance of Deepening Our Knowledge and Understanding Of

The Importance of Deepening our Knowledge and Understanding of the Faith The Importance of Deepening our Knowledge and Understanding of the Faith A compilation of extracts from the Bahá'í Writings Prepared by the Research Department of the Universal House of Justice Bahá'í World Centre Baha'i Publishing Trust, Wilmette, Illinois 60091 Copyright by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of Canada 1983 Also in the Compilation of Compilations Vol. I, pp. 187-234 CONTENTS Extracts from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh Extracts from the Writings of `Abdu'l-Bahá Extracts from the Utterances of `Abdu'l-Bahá Extracts from Letters written by Shoghi Effendi Extracts from Letters written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi Extracts from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh 1. Recite ye the verses of God every morn and eventide. Whoso faileth to recite them hath not been faithful to the Covenant of God and His Testament, and whoso turneth away from these holy verses in this Day is of those who throughout eternity have turned away from God. Fear ye God, O My servants, one and all. Bahá'u'lláh, The Kitab-i-Aqdas, p. 73 2. Were any man to taste the sweetness of the words which the lips of the All-Merciful have willed to utter, he would, though the treasures of the earth be in his possession, renounce them one and all, that he might vindicate the truth of even one of His commandments, shining above the Dayspring of His bountiful care and loving-kindness. Bahá'u'lláh, A Synopsis and Codification of the Laws and Ordinances of Kitab-i-Aqdas, p. -

Some Aspects of Bahá'í Ethics

The 20th Hasan M. Balyuzi Memorial Lecture Some Aspects of Bahá’í Ethics UDO SCHAEFER I am really overwhelmed and deeply touched by your warm-hearted wel- come and introduction. It is an unexpected, great honor to have been cho- sen by the Association to present the Hasan M. Balyuzi Memorial Lecture. I would like to express my sincerest gratitude and that of my wife for this invitation. The material that I am presenting—some aspects of Bahá’í ethics—is taken from the draft of a forthcoming book, Bahá’í Ethics in Light of Scripture.1 A systematic presentation of the new standard of values is, as I feel, not only timely, it is rather a matter of urgency in the face of the increasing disintegration of traditional morality and the truly apocalyp- tic dimension of spreading immorality all over the world. When choosing my topic for this conference I had to decide between an outline of the new morality which, in the given time frame, could not have been more than a general survey, or some few central issues that can be dealt with more in depth. I chose the latter option, inasmuch as I can refer to my article pub- lished in the Bahá’í Studies Review, “The New Morality: An Outline.” Let me start with a few general remarks on ethics: The term derives from the Greek ethikos which pertains to ethos (character). Ethics as part of practical philosophy is also called “moral philosophy,”2 and, if it is a religious ethics based on revelation (a revelatory ethics like Bahá’í ethics), one can call it “moral theology,” as it is termed in Catholicism. -

Examples of the Bahá'í Faith's Outward Expressions

Examples of the Bahá’í Faith’s Outward Expressions Photo taken in 1894 Carmel means “Vineyard of the Lord”. Mount Carmel, of which the prophet Daniel called “the glorious mountain”. (KJV-Daniel 11:45) The New English Bible translation is “the holy hill, the fairest of all hills”. Mount Carmel, the home of the prophet Elijah, who challenged 450 prophets of Baal to prove their religious claims. “Now therefore send, and gather to me all Israel unto mount Carmel, and the prophets of Baal four hundred and fifty, and the prophets of the groves four hundred, which eat at Jezebel's table. (KJV, 3 Kings 18:19-29) He destroyed them, as well as the pervasive belief in Baalim, a false god. Caves where he lived in this Mountain are still revered. Mount Carmel, of which the Prophet Isaiah extolled “And it shall come to pass in the last days, [that] the mountain of the Lord’s house shall be established in the top of the mountains, and shall be exalted above the hills; and all nations shall flow unto it.” (KJV, Isaiah 2:2-3) And again, “…let us go up to the mountain of the Lord, to the house of the God of Jacob; and he will teach us his ways, and we will walk in his paths: for out of Zion shall go forth the law, and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.” (KJV, Isaiah 11:3) And again, “They shall not hurt nor destroy in all my holy mountain: for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord, as the waters cover the sea.” (KJV, 11:9) Mount Carmel, where Bahá’u’lláh (trans. -

Some Answered Questions

ACCA 1904-1906 SOME ANSWERED QUESTIONS SOME ANSWERED QUESTIONS COLLECTED AND TRANSLATED FROM THE PERSIAN OF 'ABDU'L-BAHA I! BY LAURA CLIFFORD BARNEY PHILADELPHIA COMPANY J. B. LIPPINCOTT TRUBNER & CO. LTD. LONDON: KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, 1908 All rights reserved AJ3 H0FFITT. Edinburgh : T. and A. COBSTAJJLIS, Printera to His Majesty INTRODUCTION 'I HAVE given to you my tired moments/ were the 1 words of 'Abdu'1-Baha as he rose from table after answering one of my questions. As it was on this so it continued between the day, ; hours of work, his fatigue would find relief in renewed he was able to at activity ; occasionally speak length ; but often, even though the subject might require more time, he would be called away after a few and even weeks would in moments ; again, days pass, which he had no opportunity of instructing me. But I could well be patient, for I had always before me the greater lesson the lesson of his personal life. During my several visits to Acca, these answers were written down in Persian while 'Abdu'1-Baha spoke, that I not with a view to publication, but simply At first might have them for future study. they of the had to be adapted to the verbal translation I had a interpreter; and later, when acquired slight This knowledge of Persian, to my limited vocabulary. and for no accounts for repetition of figures phrases, 1 ' Bahaism. He is also known, Abdu'1-Baha is the great teacher of name of Abbas Efendi. For further and especially in Syria, under the information see article on Bahaism, page vii.