Religion Asserts That Its Central Concerns Are Discovering Truth and Implementing the Measures Called for by That Truth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baha'u'llah As Fulfilment of the Theophanic Promise in the Sermons of Imam 'Alí Ibn Abí Ṭálib

OJBS: Online Journal of Bahá‟í Studies Volume 1 (2007), 89-113 URL: http://www.ojbs.org ISSN 1177-8547 Baha’u’llah as fulfilment of the theophanic promise in the Sermons of Imam 'Alí ibn Abí Ṭálib Translation of al Ṭutunjiyya, Iftikhár and Ma'rifat bin-Nurániyyat Dr. Khazeh Fananapazir Leicester, U.K., Independent Scholar Translator's Introduction The Founders of world religions, in Baha‟i discourse, the Manifestations of God, relate their claims and their utterances to the language and beliefs of the peoples to whom they come.1 Thus Jesus Christ stated at the outset of his mission: "Think not that I have come to destroy the Law and the Prophets. I have not come to destroy but to fulfil."2 The Qur'án repeatedly states that it confirms the Gospel and the Torah, affirming that the Prophet's advent has been mentioned in the Torah and the Evangel. The Bábí and Bahá'í Revelations are also intimately related to their Islamic background and their Judaeo-Christian heritage. As the Guardian of the Bahá'í Faith, says, "[The Bahá'ís] must strive to obtain from sources that are authoritative and unbiased a sound knowledge of the history and tenets of Islam, the source and background of their Faith, and approach reverently and with a mind purged from pre-conceived ideas the study of the Qur'án which, apart from the sacred scriptures of the Bábí and Bahá'í Revelations, constitutes the only Book which can be regarded as an absolutely authenticated repository of the Word of God."3 But what is most remarkable is the frequent reference to particular verses, particular traditions (ḥadiths), particular tropes of Judaism, Christianity and Islam. -

• Christopher Buck Phd Jd Curriculum Vitae(2017) 1

• CHRISTOPHER BUCK PHD JD CURRICULUM VITAE (2017) 1 PROFESSIONAL LEGAL EXPERIENCE 2007 – present Pribanic & Pribanic, LLC (White Oak, Pennsylvania) • Position: Associate Attorney. • Profle: http://pribanic.com/attorneys/christopher-buck/ (“My professional goal is to try to make sure that my cases settle without having to go to trial. In my over eight years of practice so far, Victor Pribanic has not tried a single one of my cases so far. That’s a pretty good track record.”) • Bar Admissions: Bar of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania (2007); U.S. District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania (2007). • Practice areas: Medical malpractice, wrongful death, crashworthiness, products liability, personal injury. Research and write briefs on any legal issue, as needed. Settled four cases for $2.5 million in 2012. • Legal CV: For “Representative Cases” and “Legal Publications,” see Buck’s Legal CV. • Lead Attorney: Victor H. Pribanic, Esq., Best Lawyers, “Lawyer of the Year, 2017” (Medical Malpractice Law, Plaintiffs, Pittsburgh); “Lawyer of the Year, 2015” (Product Liability Litigation, Plaintiffs, Pittsburgh); Best Lawyers, “Lawyer of the Year, 2014” (Medical Malpractice Law, Plaintiffs, Pittsburgh Area). PROFESSIONAL ACADEMIC EXPERIENCE 2001 – present Wilmette Institute (Wilmette, IL) • Position: Faculty (Distance Education). • Courses Taught: Summons of the Lord of Hosts (10-Oct-17); The Kitab-i-Iqan: An Introduction (1-Aug-17); Gems of Divine Mysteries and Other Early Tablets by Baha’u’llah (10-May-17); Bahá’u’lláh’s Early Mystic Writings -

Acquiring Virtues and Developing Character?

Becoming A Brilliant Star Character Development Why Should We Acquire Virtues And Develop Our Character? The Purpose And Aim Of The Manifestation Of God Is Character Development 1. The purpose of the one true God in manifesting Himself is to summon all mankind to truthfulness and sincerity, to piety and trustworthiness, to resignation and submissiveness to the Will of God, to forbearance and kindliness, to uprightness and wisdom. His object is to array every man with the mantle of a saintly character, and to adorn him with the ornament of holy and goodly deeds. Bahá'u'lláh: Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá'u’lláh, p. 299 2. The aim of this Wronged One in sustaining woes and tribulations, in revealing the Holy Verses and in demonstrating proofs hath been naught but to quench the flame of hate and enmity, that the horizon of the hearts of men may be illumined with the light of concord and attain real peace and tranquillity. From the dawning-place of the divine Tablet the day-star of this utterance shineth resplendent, and it behoveth everyone to fix his gaze upon it: We exhort you, O peoples of the world, to observe that which will elevate your station. Hold fast to the fear of God and firmly adhere to what is right. Verily I say, the tongue is for mentioning what is good, defile it not with unseemly talk. God hath forgiven what is past. Henceforward everyone should utter that which is meet and seemly, and should refrain from slander, abuse and whatever causeth sadness in men. -

July 2015 Enewsletter

July 2015 eNewsletter Celebrating Twenty Years Starting Today, and There's Still Plenty of Space! A new course on some of Baha'u'llah's earliest and most profound Web Talk No. 7: Susanne M. Alexander Discussing "Healthy, Unified Marriages as tablets Service to Humanity" on August 30 Mark your calendars now for a Web Gems of Divine Mysteries and Other Talk at the end of the summer by Susanne M. Alexander on the topic of Early Tablets by Baha'u'llah marriage as a service to humanity. Click here to continue>> One in a series of courses on the revelation of Baha'u'llah Web Talk No. 6 Now on YouTube: Lead Faculty: Robert Stockman Dr. Sandra Lynn Hutchison Offers a Technique Faculty: Daniel Gebhardt, Daniel Pschaida for Accessing the Meaning of the Bahá'í Revelation Duration of course: Seven weeks (July 1 - August 18, 2015) Read a summary of Dr. Hutchison's simple technique for finding the In Gems of Divine Mysteries and Other Early Tablets by "hidden gift" in the writings of Baha'u'llah we will examine the Javahiru'l-Asrar (Gems of Baha'u'llah, the Bab, and 'Abdu'l- Divine Mysteries), a mystic work similar to both the Seven Baha, and then treat yourself to Valleys and the Kitab-i-Iqan. We will also study several listening to the YouTube video of shorter but very important works by Baha'u'llah, Sahifiy-i- her talk. Shattiyyih (Book of the River), the Tablet of the Holy Click here to continue>> Mariner, Shikkar-Shikan-Shavand, and Lawh-i-Ayyub (Tablet of Job), all of which exist in official translation or reliable Anniversary Web Talks, August through provisional translation. -

A Journey Through the Seven Valleys1 of Bahá'u'lláh

A Journey through t he Seven Valle ys A Journey through the Seven Valleys1 of Bahá’u’lláh by Ghasem Bayat Preamble n this brief journey through the Seven Va l l e y s2 of Bahá’u’lláh, we will partake of its spiritual bounties, focus on its principal message, tune our hearts to the teachings it enshrines, marvel at its masterful composition Iand form, and recognize some of the distinctive features of this book as compared with Islamic mystic writ- ings. This brief journey is at best an introduction to this Epistle, and is intended to encourage the readers to embark on an in-depth study of the Seven Valleys to receive the full measure of love and life it off e r s . The Historical Background This Epistle of Bahá’u’lláh was revealed during the Baghdad period, circa 1862 C .E. It was revealed in answer to questions raised by S ha yk h M u h y i ’ d - D í n ,3 the judge of K hániqayn, a town located in Iraqi Kurdistan, northeast of Baghdad, and near the Iranian border. The words of the beloved Guardian in describing the significance of this Epistle and its relation to other Writings of Bahá’u’lláh provides us with a perspective on this book: To these two outstanding contributions to the world’s religious literature [the Kitáb-i-ˆqán and the Hidden Words], occupying respectively, positions of unsurpassed preeminence among the doctrinal and ethical Writings of the Author of the Bahá’í Dispensation, was added, during that same period, a treatise that may well be regarded as His greatest mystical composition, designated as the “Seven Valleys,” -

Revelation & Social Reality

Revelation & Social Reality Learning to Translate What Is Written into Reality Paul Lample Palabra Publications Copyright © 2009 by Palabra Publications All rights reserved. Published March 2009. ISBN 978-1-890101-70-1 Palabra Publications 7369 Westport Place West Palm Beach, Florida 33413 U.S.A. 1-561-697-9823 1-561-697-9815 (fax) [email protected] www.palabrapublications.com Cover photograph: Ryan Lash O thou who longest for spiritual attributes, goodly deeds, and truthful and beneficial words! The outcome of these things is an upraised heaven, an outspread earth, rising suns, gleaming moons, scintillating stars, crystal fountains, flowing rivers, subtle atmospheres, sublime palaces, lofty trees, heavenly fruits, rich harvests, warbling birds, crimson leaves, and perfumed blossoms. Thus I say: “Have mercy, have mercy O my Lord, the All-Merciful, upon my blameworthy attributes, my wicked deeds, my unseemly acts, and my deceitful and injurious words!” For the outcome of these is realized in the contingent realm as hell and hellfire, and the infernal and fetid trees, as utter malevolence, loathsome things, sicknesses, misery, pollution, and war and destruction.1 —BAHÁ’U’LLÁH It is clear and evident, therefore, that the first bestowal of God is the Word, and its discoverer and recipient is the power of understanding. This Word is the foremost instructor in the school of existence and the revealer of Him Who is the Almighty. All that is seen is visible only through the light of its wisdom. All that is manifest is but a token -

Solace of the Heart’

Solace of the Heart Peter Mputle Revised Edition 2020 1 Dedicated to all those inquiring minds, for they are bound to tread a path of search and discover a hidden Treasure laid within a mystic cave of Eternity. 2 Contents Foreword 4 Section 1: Spirituality 1. Lifeless life 6 2. High Call 7 3. Secret of Ages 8 4. The Glory of God 9 5. Fearless Warrior 10 6. Crying Voice 11 7. Yearning 12 8. The Last Breath 12 9. Rest not in Peace 13 10. Synopsis 14 11. Arise 15 12. Chocolate of God 16 13. Chocolate Skin 16 14. Remarkable ‘One’ 17 15. A Thousand Years 18 16. Beware! 19 17. What...! 20 18. The Inseparable Two 21 19. Mortal Separation 21 20. The ‘WORD’ 22 21. Order 23 22. Embodiment of real Life 24 23. Bread of Heaven 25 24. The Sadratu’l Muntaha 26 25. Angel Gabriel 27 26. Triangular Love 28 27. Understanding 28 28. Divine Utterances 29 Section 2: Reflections on the ‘Seven Valleys’ 29. The Path of Search 30 30. The Valley of Love 31 31. Valley of Knowledge 32 32. Unity 33 33. Pure Contentment 34 34. Wonderment 35 35. True Poverty 36 Section 3: Temper 36. Lamentation of the Desolate 37 37. Forgotten Love 38 38. Diminishing Love 38 39. Drooping Heart 38 40. Layli 39 41. Lady Layli 40 42. Spurious Assumptions 41 43. Voices 41 References 42 3 Foreword The poems in this booklet were inspired by the Holy Writings of the Bahá’í Faith. The evidence of this is the type of language and words used which symbolises the Shakespearean era and the King James Version of Bible. -

Buddhism and the Bahá'í Writings: an Ontological Rapprochement

Buddhism and the Bahá’í Writings An Ontological Rapprochement * Ian Kluge Buddhism is one of the revelations recognised by the Bahá’í Faith as being divine in origin and, therefore, part of humankind’s heritage of guidance from God. This religion, which has approximately 379 million followers 1 is now making significant inroads into North America and Europe where Buddhist Centres are springing up in record numbers. Especially because of the charismatic leader of Tibetan Prasangika Buddhism, the Dalai Lama, Buddhism has achieved global prominence both for its spiritual wisdom as well as for its part in the struggle for an independent Tibet. Thus, for Bahá’ís there are four reasons to seek a deeper knowledge of Buddhism. In the first place, it is one of the former divine revelations and therefore, inherently interesting, and second, it is one of the ‘religions of our neighbours’ whom we seek to understand better. Third, a study of Buddhism also allows us to better understand Bahá’u’lláh’s teaching that all religions are essentially one. (PUP 175) Moreover, if we wish to engage in intelligent dialogue with them, we must have a solid understanding of their beliefs and how they relate to our own. We shall begin our study of Buddhism and the Bahá’í Writings at the ontological level because that is the most fundamental level at which it is possible to study anything. Ontology, which is a branch of metaphysics, 2 concerns itself with the subject of being and what it means ‘to be,’ and the way in which things are. -

Syllabus-Bahaullahs

Director: Dr. Robert H. Stockman www.wilmetteinstitute.org Email: [email protected] Voice: (877)-WILMETTE Course: ST131: Bahá'u'lláh's Revelation: A Systematic Survey Instructors: Robert Stockman: https://wilmetteinstitute.org/faculty_bios/robert-stockman/ Nima Rafiei: https://wilmetteinstitute.org/faculty_bios/nima-rafiei/ Course Description: The writings of Bahá'u'lláh (1817-92), prophet-founder of the Bahá'í Faith, is estimated to comprise 18,000 works and in excess of six million words, composed in Arabic, Persian, and a unique mixture of both. Approximately 5-7% has been translated into English, but the works available are the most important. In this course we will undertake a systematic introduction to twenty of Bahá'u'lláh’s most important works, ranging from the Rashḥ-i-‘Amá (1853) to Epistle to the Son of the Wolf (1892). We will study the works in chronological order of composition, examining the themes in the works, topics that Bahá'u'lláh progressively revealed during His ministry, and related tablets wherever possible. We will not read most of the twenty works in their entirety but will study significant passages and sections from them. The course will appeal to anyone seeking a deeper understanding of Bahá'u'lláh’s immense corpus. Learning Outcomes of Wilmette Institute courses relevant to this course: Knowledge: Demonstrate knowledge and interdisciplinary insights gained from the course and service learning. Abilities: Independently investigate to discern fact from conjecture. Engage in public discourse, consultation, service -

Provisional Translations of Selected Writings of the Báb, Bahá׳U׳Lláh

Provisional Translations of Selected Writings of the Báb, Baháʼuʼlláh, and ʻAbdu’l-Bahá by Peyman Sazedj Translations originally posted at peyman.sazedj.org, reconstructed from archive.org Contents The Báb 1. Order of the Verses (Persian Bayán 3:16) 2. The Seven Stages of Creation 3. On Divine Nonfulfillment (Badá) Baháʼuʼlláh 4. Addressed to an Ancestor: "Forfeit Not the Brief Moments of Your Lives!" 5. The Meaning of Pioneering 6. Tablet of Visitation of Badí 7. The Stages of Contentment (Riḍá) 8. On Divine Tests 9. The Maiden of Divine Mystery 10. A Most Weighty Counsel 11. The Voice of the Heart of the World 12. The Three Types of Attachment 13. From the Kitáb -i-Badí: About the Short Time Span between the Revelation of the Báb and Baháʼuʼlláh 14. The Proof of the Next Manifestation 15. Interpretation of “He Employeth the Angels as Messengers, with Pairs of Wings, Two, Three and Four…” ʻAbdu’l-Bahá 16. What Youth Must Master 17. The Middle Way 18. Both Motion and Stillness are of God 19. Life on other Planets 20. About the Jinn 21. Ignorance of Self 22. The Ruby Tablet and the fifth Tablet of Paradise 23. Allusions to the Covenant in the Hidden Words 24. Interpretation of the Hidden Word: "In the Night Season..." 25. The Five Standards of Acquiring Knowledge 26. Prophets Mentioned in the Qu'rán, Zoroaster, and Mahábád 27. Prayer for Visiting the Shrine of Baháʼuʼlláh The Báb 1. The Order of the Verses (Persian Bayán 3:16) Let him who is able render the order of the Bayán in whatever manner is sweetest, though it be rendered in a thousand ways. -

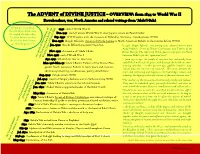

The ADVENT of DIVINE JUSTICE – OVERVIEW: from 1844 to World War II

The ADVENT of DIVINE JUSTICE – OVERVIEW: from 1844 to World War II Dawnbreakers, war, North America and related writings from ‘Abdu’l-Bahá for groups, read aloud: 1945: end of World War II the title block above, then the angled Dawnbreakers Dec. 1941: the US enters World War II after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor line from bottom up, then Sep. 1939: WWII begins with the invasion of Poland by Germany, Canada enters WWII the timeline from bottom Dec. 1938: Shoghi Effendi’s Advent of Divine Justice to North American Bahá’ís in the months before WWII up, then the green text Jan. 1922: Shoghi Effendi appointed Guardian In 1938, Shoghi Effendi, anticipating war, adapted themes from ‘Abdu’l–Bahá’s Secret of Divine Civilization and Tablets of the Nov. 1921: Ascension of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá Divine Plan for The Advent of Divine Justice to prepare the North Nov. 1918: end of World War I American Bahá’ís for the “appointed time”. Apr. 1917: US declares war on Germany “…from age to age, the temple of existence has continually been Mar. 1916–Mar. 17: ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Tablets of the Divine Plan embellished with a fresh grace, and distinguished with an ever- varying splendor… in this present age, godlike impulses may guides North American Bahá’ís to teach peace and oneness; radiate from the conscience of mankind… We must…promote the advocates pioneering, steadfastness, purity, detachment peace and well-being and happiness, the knowledge, culture and Aug. 1914: Canada enters WWI industry, the dignity, value and station, of the entire human race.” Jul. -

The Importance of Deepening Our Knowledge and Understanding Of

The Importance of Deepening our Knowledge and Understanding of the Faith The Importance of Deepening our Knowledge and Understanding of the Faith A compilation of extracts from the Bahá'í Writings Prepared by the Research Department of the Universal House of Justice Bahá'í World Centre Baha'i Publishing Trust, Wilmette, Illinois 60091 Copyright by the National Spiritual Assembly of the Baha'is of Canada 1983 Also in the Compilation of Compilations Vol. I, pp. 187-234 CONTENTS Extracts from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh Extracts from the Writings of `Abdu'l-Bahá Extracts from the Utterances of `Abdu'l-Bahá Extracts from Letters written by Shoghi Effendi Extracts from Letters written on behalf of Shoghi Effendi Extracts from the Writings of Bahá'u'lláh 1. Recite ye the verses of God every morn and eventide. Whoso faileth to recite them hath not been faithful to the Covenant of God and His Testament, and whoso turneth away from these holy verses in this Day is of those who throughout eternity have turned away from God. Fear ye God, O My servants, one and all. Bahá'u'lláh, The Kitab-i-Aqdas, p. 73 2. Were any man to taste the sweetness of the words which the lips of the All-Merciful have willed to utter, he would, though the treasures of the earth be in his possession, renounce them one and all, that he might vindicate the truth of even one of His commandments, shining above the Dayspring of His bountiful care and loving-kindness. Bahá'u'lláh, A Synopsis and Codification of the Laws and Ordinances of Kitab-i-Aqdas, p.