Hot Topics for the Future of PRC and Hong Kong, China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media

China Perspectives 2018/3 | 2018 Twenty Years After: Hong Kong's Changes and Challenges under China's Rule Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media Francis L. F. Lee Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.8009 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2018 Number of pages: 9-18 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Francis L. F. Lee, “Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media”, China Perspectives [Online], 2018/3 | 2018, Online since 01 September 2018, connection on 21 September 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/8009 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives. 8009 © All rights reserved Special feature China perspectives Changing Political Economy of the Hong Kong Media FRANCIS L. F. LEE ABSTRACT: Most observers argued that press freedom in Hong Kong has been declining continually over the past 15 years. This article examines the problem of press freedom from the perspective of the political economy of the media. According to conventional understanding, the Chinese government has exerted indirect influence over the Hong Kong media through co-opting media owners, most of whom were entrepreneurs with ample business interests in the mainland. At the same time, there were internal tensions within the political economic system. The latter opened up a space of resistance for media practitioners and thus helped the media system as a whole to maintain a degree of relative autonomy from the power centre. However, into the 2010s, the media landscape has undergone several significant changes, especially the worsening media business environment and the growth of digital media technologies. -

Hongkong a Study in Economic Freedom

HongKOng A Study In Economic Freedom Alvin Rabushka Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace Stanford University The 1976-77 William H. Abbott Lectures in International Business and Economics The University of Chicago • Graduate School of Business © 1979 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. ISBN 0-918584-02-7 Contents Preface and Acknowledgements vn I. The Evolution of a Free Society 1 The Market Economy 2 The Colony and Its People 10 Resources 12 An Economic History: 1841-Present 16 The Political Geography of Hong Kong 20 The Mother Country 21 The Chinese Connection 24 The Local People 26 The Open Economy 28 Summary 29 II. Politics and Economic Freedom 31 The Beginnings of Economic Freedom 32 Colonial Regulation 34 Constitutional and Administrative Framework 36 Bureaucratic Administration 39 The Secretariat 39 The Finance Branch 40 The Financial Secretary 42 Economic and Budgetary Policy 43 v Economic Policy 44 Capital Movements 44 Subsidies 45 Government Economic Services 46 Budgetary Policy 51 Government Reserves 54 Taxation 55 Monetary System 5 6 Role of Public Policy 61 Summary 64 III. Doing Business in Hong Kong 67 Location 68 General Business Requirements 68 Taxation 70 Employment and Labor Unions 74 Manufacturing 77 Banking and Finance 80 Some Personal Observations 82 IV. Is Hong Kong Unique? Its Future and Some General Observations about Economic Freedom 87 The Future of Hong Kong 88 Some Preliminary Observations on Free-Trade Economies 101 Historical Instances of Economic Freedom 102 Delos 103 Fairs and Fair Towns: Antwerp 108 Livorno 114 The Early British Mediterranean Empire: Gibraltar, Malta, and the Ionian Islands 116 A Preliminary Thesis of Economic Freedom 121 Notes 123 Vt Preface and Acknowledgments Shortly after the August 1976 meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society, held in St. -

Bay to Bay: China's Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US And

June 2021 Bay to Bay China’s Greater Bay Area Plan and Its Synergies for US and San Francisco Bay Area Business Acknowledgments Contents This report was prepared by the Bay Area Council Economic Institute for the Hong Kong Trade Executive Summary ...................................................1 Development Council (HKTDC). Sean Randolph, Senior Director at the Institute, led the analysis with support from Overview ...................................................................5 Niels Erich, a consultant to the Institute who co-authored Historic Significance ................................................... 6 the paper. The Economic Institute is grateful for the valuable information and insights provided by a number Cooperative Goals ..................................................... 7 of subject matter experts who shared their views: Louis CHAPTER 1 Chan (Assistant Principal Economist, Global Research, China’s Trade Portal and Laboratory for Innovation ...9 Hong Kong Trade Development Council); Gary Reischel GBA Core Cities ....................................................... 10 (Founding Managing Partner, Qiming Venture Partners); Peter Fuhrman (CEO, China First Capital); Robbie Tian GBA Key Node Cities............................................... 12 (Director, International Cooperation Group, Shanghai Regional Development Strategy .............................. 13 Institute of Science and Technology Policy); Peijun Duan (Visiting Scholar, Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies Connecting the Dots .............................................. -

Business Cycles in a Small Open Economy Model: the Case of Hong Kong.∗

Business cycles in a small open economy model: The case of Hong Kong.∗ Paulina Etxeberria Garaigortay Amaia Izaz The University of the Basque Country. January, 2011 Abstract This paper analyzes the business cycle properties of the Hong Kong economy du- ring the 1982-2004 period, which includes the financial crisis experienced in Hong Kong in 1997-98. We show that output, output growth rate and real interest rates volatilities in Hong Kong are higher than their respective average volatilities among developed economies. In this paper, we build a stochastic neoclassical small open economy model that seeks to replicate the main business cycle characteristics of Hong Kong, and through which we try to quantify the role played by exogenous Total Factor Productivity and real interest rates shocks. The main finding is that, in order to ex- plain the Hong Kong business cycle characteristics, the trend volatility has to be higher than the volatility of the transitory fluctuations around the trend, and that the coun- try risk spread is the responsible for both the high variability and its countercyclicality. Keywords: Asian Financial Crisis, Small Open Economy, Neoclassical model. JEL Classification: E13, E32, F41. ∗We thank Cruz Angel´ Echevarr´ıa for useful comments. This paper was presented at the All China Economics (ACE) International Conference, Hong Kong, 2006, XXXIII Symposium of Economic Analysis, Spain, 2007, DEGIT XVI Dynamics, Economic Growth and International Trade, Los Angeles, USA, 2009. Financial support from Universidad del Pa´ısVasco MACLAB, project IT-241-07, and Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovaci´on,project ECO2009-09732 are gratefully acknowledged. Any remaining errors are the authors' responsibility. -

Political Economy of Hong Kong's Open Skies Legal Regime

The Political Economy of Hong Kong's "Open Skies" Legal Regime: An Empirical and Theoretical Exploration MIRON MUSHKAT* RODA MUSHKAT** TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN TRO DU CTIO N .................................................................................................. 38 1 II. TOW ARD "O PEN SKIES". .................................................................................... 384 III. H ONG K ONG RESPONSE ..................................................................................... 399 IV. QUEST FOR ANALYTICAL EXPLANATION ............................................................ 410 V. IMPLICATIONS FOR INTERNATIONAL REGIMES .................................................... 429 V 1. C O N CLU SION ..................................................................................................... 4 37 I. INTRODUCTION Hong Kong is widely believed to epitomize the practical virtues of the neoclassical economic model. It consistently outranks other countries in terms of the criteria incorporated into the Heritage Foundation's authoritative Index of Economic Freedom. The periodically challenging and potentially * Adjunct Professor of Economics and Finance, Syracuse University Hong Kong Program. ** Professor of Law and Director of the Center for International and Public Law, Brunel Law School, Brunel University; and Honorary Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Hong Kong. tumultuous transition from British to Chinese rule has thus far had no tangible impact on its status in this respect. A new post-1997 political -

Asian Development Outlook Supplement June 2020

ASIAN DEVELOPMENT OUTLOOK SUPPLEMENT JUNE 2020 HIGHLIGHTS LOCKDOWN, LOOSENING, AND Developing Asia will barely grow in 2020, the 0.1% forecast in this ASIA’S GROWTH PROSPECTS Supplement is a further downward revision from 2.2% projected in April in Asian Development Outlook 2020 and the region’s slowest growth rate in 6 decades. From this low base, growth will Recent developments pick up to 6.2% in 2021. Excluding Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has continued to spread, and containment newly industrialized economies, measures have greatly disrupted economic activity. In the 2 months since Asian regional growth is forecast at 0.4% Development Outlook 2020 was released on 3 April, the number of COVID-19 in 2020 and 6.6% in 2021. cases worldwide has risen from less than 1 million to over 7 million by 12 June, Growth prospects for East Asia in with developing Asia accounting for 10.7% of the total (Figure 1). Domestic 2020 are downgraded from 2.0% to outbreaks have occurred in more economies in the region, with 21 of the 46 1.3%. This reflects expansion in the Asian Development Bank (ADB) developing member economies recording more People’s Republic of China by only than 1,000 cases each. In response, many governments have imposed lockdowns 1.8% in 2020, rebounding to 7.4% in of varying stringency and duration, with average stringency higher in South and 2021 and lifting subregional growth Central Asia and lower in East Asia (Figure 2). Many economies are now starting to 6.8%. to exit their lockdowns. -

British Economic Interests and the Decolonization of Hong Kong

James Blair Historical Review Volume 9 Issue 2 Article 3 2019 Setting the Sun on the British Empire: British Economic Interests and the Decolonization of Hong Kong Abby S. Whitlock College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/jbhr Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Whitlock, Abby S. (2019) "Setting the Sun on the British Empire: British Economic Interests and the Decolonization of Hong Kong," James Blair Historical Review: Vol. 9 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/jbhr/vol9/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in James Blair Historical Review by an authorized editor of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Whitlock: British Economic Interests and the Decolonization of Hong Kong Setting the Sun on the British Empire: British Economic Interests and the Decolonization of Hong Kong Abby Whitlock Ruled under the Union Jack from 1841 to 1997, the British acquired Hong Kong during the second wave of European colonialism focused on Asia. Along with countries such as Germany, France, Portugal, and the Netherlands, Britain looked for new areas to provide support for mercantile capitalism and manufacturing developments. Under Britain’s 154 years of rule, the stable nature of British government systems and thorough economic investments caused Hong Kong to become a wealthy international trade center in the twentieth century. Despite these economic investments and interests, the nature of the New Territories Lease under which Britain acquired the totality of Hong Kong, which was to expire in 1997, opened the question of who was to control Hong Kong. -

Asian Economic Development: a Primer

Arndt-Corden Department of Economics Crawford School of Public Policy ANU College of Asia and the Pacific Asian economic development: A primer Prema-chandra Athukorala Crawford School of Public Policy Australian National University [email protected] March 2021 Working Papers in Trade and Development No. 2020/07 This Working Paper series provides a vehicle for preliminary circulation of research results in the fields of economic development and international trade. The series is intended to stimulate discussion and critical comment. Staff and visitors in any part of the Australian National University are encouraged to contribute. To facilitate prompt distribution, papers are screened, but not formally refereed. Copies are available at https://acde.crawford.anu.edu.au/acde-research/working- papers-trade-and-development Asian Economic Development: A Primer* Prema-chandra Athukorala Crawford School of Public Policy Australian National University [email protected] Abstract During the post-World War 11 era, the process of economic transformation in Asia has been more rapid and extensive than in any other region in the world. With the Asia-wide embrace of market-oriented policy reforms and following the meteoric rise of China and India’s awakening from economic slumber, the twenty-first century has come to be labelled the ‘Asian Century’. The purpose of this paper is to introduce the nonspecialized reader to a selection of published papers that provides a comprehensive picture of economic policymaking and performance of these countries. The compilation of the collection was motivated by both the economic significance of the region in the global economy and the pivotal role played by Asia-focused research in the enrichment of the subject area of development economics. -

International Report

SECONd Quarter 2019 INTERNATIONAL REPORT CONSTRUCTION MARKET INTELLIGENCE INDEPENDENT CONSULTANTS, LOCAL KNOWLEDGE AND EXPERTISE, GLOBAL NETWORK The strength of Rider Levett Bucknall (RLB), the Each RLB office contributes to the global intelligence largest independent and most geographically by providing current insights into the local conditions prevalent construction cost consultancy of its kind and trends that impact the construction industry in the world, is that it has the foremost construction within that region. Information that is gathered and intelligence available to it. disseminated by each local office includes: RLB collects and collates current construction data § Forecast Tender Price Index and forecast trends on a global, regional, country, § RLB Construction Market Activity Cycle city and sector basis. The RLB International Report, § Key building type cost ranges in local currencies published half-yearly, provides a snapshot of construction market intelligence provided by the RLB network of offices around the globe. TENDER PRICE INDEX BUILDING COST CONSTRUCTION MARKET RLB’s Tender Price Index RLB’s Building Cost Ranges INTELLIGENCE (TPI) showcases the historical highlighted within each regional A summary of Construction Market and forecast movements in intelligence page are based on Intelligence is provided by each construction cost inflation/ actual project construction costs. region highlighting the issues that escalation on an annual basis. Building costs are provided in are impacting the construction The TPI annual rate represents an local currencies per m2, with industry and providing key insights overall forecast of the movement the exception of Oslo and into current construction price of construction costs for the Moscow whose building costs movements. industry as a whole within the key are expressed in Euros and North cities of RLB’s network. -

Taking Back the Economy of Hong Kong?!

URSP3050 Special Topics in Urban Studies I Lam Chit Sum Salom Take Back the Economy – Case Study Report 1155038584 Taking Back the Economy of Hong Kong?! 1. Introduction and Background 1.1 Introduction The global hegemony power of capitalism has been problematic issue for a comprehensive human development (Velicu, 2014). A specific type of hegemony power is dominating the economy of Hong Kong. According to a survey done by Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies of CUHK (2011), about 50% of respondents (404 of 832) agreed that the problem of property-developer hegemony is severe. Property-developer hegemony has led to homogeneous landscape in the urban environment, diminishing of local shops which are being replaced by global chain stores, with gentrification of shopping malls to fit the taste of middle-upper end customers. People are able to satisfy all their needs in a shopping mall, from chained supermarkets such as Taste and Marketplace as well as from other global chain stores. People do not have choice. In the recent years, the situation of Hong Kong reaches its threshold, the number of anti-property-developer hegemony protests increase. People started to realize the importance and the value of street markets, and seem that this is the way for us to take back the economy. In the following, I will focus on the case of Fa Yuen Street Market, to investigate how hawking activities can take back the economy of Hong Kong. 1.2 Background 1.2.1 History of hawking development Since the nineteenth century, hawking has been a way for people to strive for a living. -

Empirical Reassessment of Bank-Based Financial Development and Economic Growth in Hong Kong

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Empirical Reassessment of Bank-based Financial Development and Economic Growth in Hong Kong Ho, Sin-Yu and Njindan Iyke, Bernard University of South Africa, Deakin University 2017 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/78920/ MPRA Paper No. 78920, posted 04 May 2017 07:32 UTC Empirical Reassessment of Bank-based Financial Development and Economic Growth in Hong Kong Abstract This paper reassesses the nexus between bank-based financial development and economic growth in Hong Kong during the period 1990 – 2014. That is, it tests whether Hong Kong follows a supply- leading or a demand-following hypothesis. Empirically, economists have generally disagreed on the nexus between bank-based financial development and economic growth. Hong Kong is a typical economy which has experienced both bank-based financial expansion and economic expansion in the last three decades. It therefore serves as a quintessence for testing this overarching debate. Using the Toda-Yamamoto test for causality and two indicators of bank-based financial development – in order to report robust results – the paper finds Hong Kong to follow the supply-leading hypothesis. This implies that the banking sector is vital in driving economic growth in Hong Kong during the study period. Policymakers in this economy will only enhance economic growth further by targeting and ensuring efficient performance of bank-based financial institutions. JEL Codes: C32; E44; G21 Keywords: Bank-based Financial Development; Economic Growth; Causality; Hong Kong 1. Introduction Do banking systems drive economic growth? Or does economic growth drive banking systems? These questions have been prominent at least since the nineteenth century. -

Study Abroad Course List 2019-2020

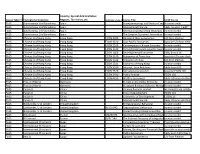

Country, Special Administrative Course Taken TermInternational and Year Institution Regions, Territories, etc. Institution Course # Course Title UCSD Course FA15 Autonomous U of Barcelona Spain Entrepreneurship and Venture CreationsNo econ credit FA15 Autonomous U of Barcelona Spain International Finance likely no econ credit* FA15 Autonomous U of Barcelona Spain International Marketing Strategies no econ credit FA15 Autonomous U of Barcelona Spain The Creative Economy: Innovation 21stno econCentury credit FA15 Chinese U of Hong Kong Hong Kong ECON 4020 Advanced Macroeconomics UD Econ elective FA15 Chinese U of Hong Kong Hong Kong ECON 3320 Asia-Pacific Economies possible UD econ elective FA15 Chinese U of Hong Kong Hong Kong ECON 2320 Contemporary Chinese Economy no econ credit FA15 Chinese U of Hong Kong Hong Kong ECON 1310 Current Hong Kong Economic Issues no econ credit FA15 Chinese U of Hong Kong Hong Kong ECON 3460 Developmental Economics likely Econ 116 FA15 Chinese U of Hong Kong Hong Kong ECON 3240 Economics of Transition possible UD econ elective FA15 Chinese U of Hong Kong Hong Kong ECON 3310 Economy of China UD Econ elective FA15 Chinese U of Hong Kong Hong Kong ECON 2311 Economy of Hong Kong no econ credit FA15 Chinese U of Hong Kong Hong Kong ECON 3530 Internet, Econ Relations likely Econ 102 FA15 Chinese U of Hong Kong Hong Kong ECON 3620 Intrnational economics possible ECON 103 FA15 Chinese U of Hong Kong Hong Kong ECON 3430 Public Finance ECON 150 FA15 Chinese U of Hong Kong Hong Kong ECON 4430 Welfare Economics likely