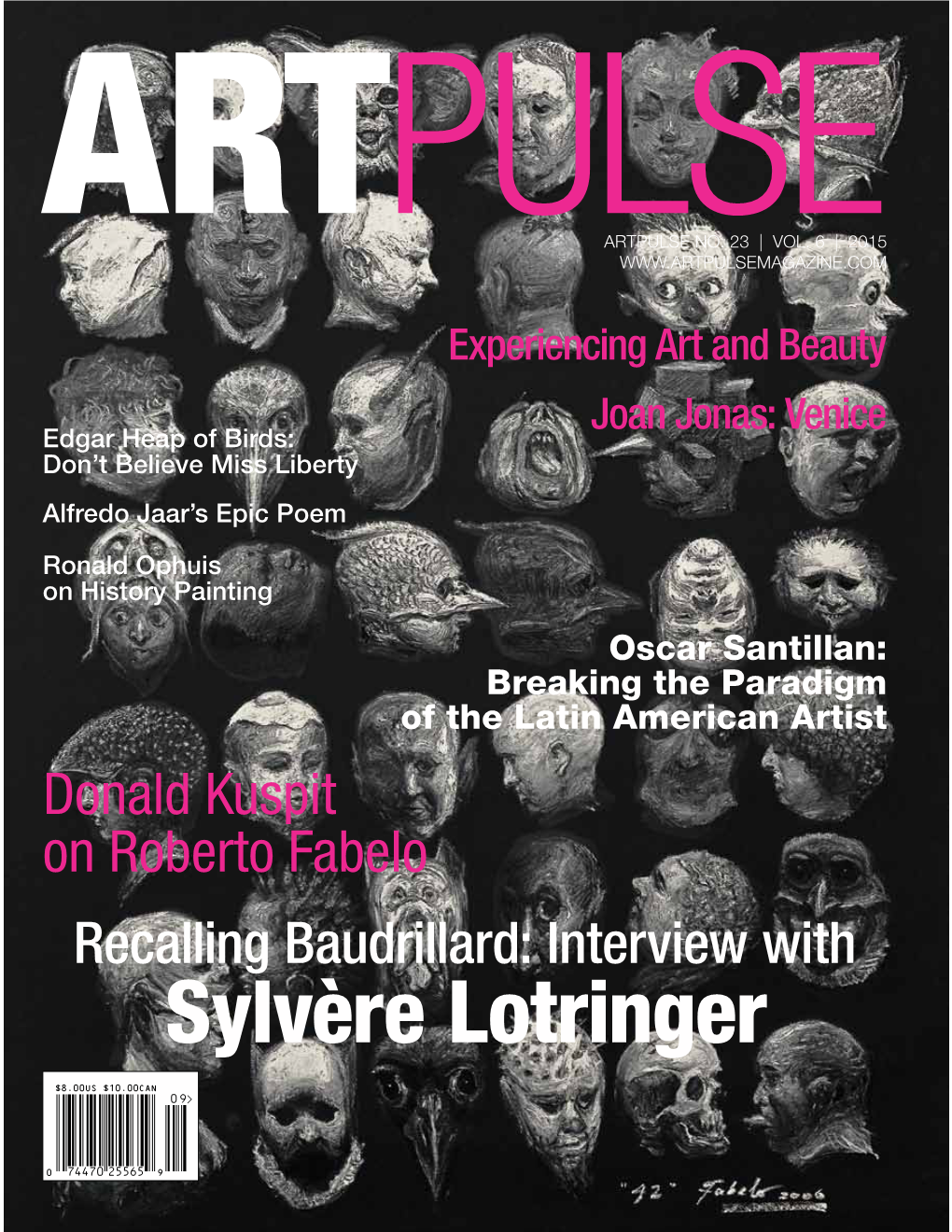

Sylvère Lotringer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH of DR. FRED OLSEN Fred Olson Was Born 28 February, 1891 in Newcastle-On-Tyne, England. at the Age of 15 He E

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF DR. FRED OLSEN Fred Olson was born 28 February, 1891 in Newcastle-on-Tyne, England. At the age of 15 he emigrated to Canada, where he entered the University of Toronto and was the recipient of the Edward Blake Scholarship in chemistry—defeating 3,000 examinees in a nation-wide competition. Olson received his BA and MA in chemistry in 1916 and 1917, respectively. Dr. Olson was awarded an honorary doctorate from Washington University, St. Louis, for his many research achievements in chemistry. In 1917 he married Florence Quittenton of Toronto. During World War I, Dr. Olson was loaned by the Canadian govern ment to the United States to assist in the manufacture of munitions. He was put in charge of US Army research at the Picatiny, New Jersey arsensal, where he became aware of the high incidence of explosions and consequent injuries and fatalities in the powder factories. As a result of his observations, Dr. Olson developed a safe and widely adopted technique for manufacturing explosives under water (ball powder). This innovation greatly reduced the hazard of explosion in the powder factories; in fact, during World War II not a single casualty was incurred by US Army personnel during the manufacture of munitions. After the War, Dr. Olson was employed by Olin-Matheson as Vice President in charge of research until his retirement. In 1960 he bought a house at the Mill Reef Club, Antigua, West Indies. There he discovered the Mill Reef archaeological site, which he called to the attention of Professor Irving Rouse of the Department of Anthropology, Yale University. -

Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Sculpture

Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Sculpture An exhibition on the centennial of their births MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Speculations in Form Eileen Costello In the summer of 1956, Jackson Pollock was in the final descent of a downward spiral. Depression and alcoholism had tormented him for the greater part of his life, but after a period of relative sobriety, he was drinking heavily again. His famously intolerable behavior when drunk had alienated both friends and colleagues, and his marriage to Lee Krasner had begun to deteriorate. Frustrated with Betty Parsons’s intermittent ability to sell his paintings, he had left her in 1952 for Sidney Janis, believing that Janis would prove a better salesperson. Still, he and Krasner continued to struggle financially. His physical health was also beginning to decline. He had recently survived several drunk- driving accidents, and in June of 1954 he broke his ankle while roughhousing with Willem de Kooning. Eight months later, he broke it again. The fracture was painful and left him immobilized for months. In 1947, with the debut of his classic drip-pour paintings, Pollock had changed the direction of Western painting, and he quickly gained international praise and recog- nition. Four years later, critics expressed great disappointment with his black-and-white series, in which he reintroduced figuration. The work he produced in 1953 was thought to be inconsistent and without focus. For some, it appeared that Pollock had reached a point of physical and creative exhaustion. He painted little between 1954 and ’55, and by the summer of ’56 his artistic productivity had virtually ground to a halt. -

I CURATING PUBLICS in BRAZIL: EXPERIMENT, CONSTRUCT, CARE

CURATING PUBLICS IN BRAZIL: EXPERIMENT, CONSTRUCT, CARE by Jessica Gogan BA. in French and Philosophy, Trinity College Dublin, 1989 MPhil. in Textual and Visual Studies, Trinity College Dublin, 1991 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2016 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jessica Gogan It was defended on April 13th, 2016 and approved by John Beverley, Distinguished Professor, Hispanic Languages and Literatures Jennifer Josten, Assistant Professor, Art History Barbara McCloskey, Department Chair and Professor, Art History Kirk Savage, Professor, Art History Dissertation Advisor: Terence Smith, Andrew W.Mellon Professor, Art History ii Copyright © by Jessica Gogan 2016 iii CURATING PUBLICS IN BRAZIL: EXPERIMENT, CONSTRUCT, CARE Jessica Gogan, MPhil/PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2016 Grounded in case studies at the nexus of socially engaged art, curatorship and education, each anchored in a Brazilian art institution and framework/practice pairing – lab/experiment, school/construct, clinic/care – this dissertation explores the artist-work-public relation as a complex and generative site requiring multifaceted and complicit curatorial approaches. Lab/experiment explores the mythic participatory happenings Domingos da Criação (Creation Sundays) organized by Frederico Morais at the Museum of Modern Art, Rio de Janeiro in 1971 at the height of the military dictatorship and their legacy via the minor work of the Experimental Nucleus of Education and Art (2010 – 2013). School/construct examines modalities of social learning via the 8th Mercosul Biennial Ensaios de Geopoetica (Geopoetic Essays), 2011. -

Testimony of Ross A. Klein, Phd Before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation Hearings on “Oversight O

Testimony of Ross A. Klein, PhD Before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation Hearings on “Oversight of the Cruise Industry” Thursday, March 1, 2012 Russell Senate Office Building Room #253 Ross A. Klein, PhD, is an international authority on the cruise ship industry. He has published four books, six monographs/reports for nongovernmental organizations, and more than two dozen articles and book chapters. He is a professor at Memorial University of Newfoundland in St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada and is online at www.cruisejunkie.com. His CV can be found at www.cruisejunkie.com/vita.pdf He can by contacted at [email protected] or [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Oral Testimony 2 Written Testimony 4 I. Safety and Security Issues 4 Onboard Crime 5 Persons Overboard 7 Abandoning a Ship in an Emergency 8 Crew Training 9 Muster Drills 9 Functionality of Life-Saving Equipment 10 Shipboard Black Boxes 11 Crime Reporting 11 Death on the High Seas Act (DOHSA) 12 II. Environmental Issues 12 North American Emission Control Area 13 Regulation of Grey Water 14 Regulation of Sewage 15 Sewage Treatment 15 Marine Sanitation Devices (MSD) 15 Advanced Wastewater Treatment Systems (AWTS) 16 Sewage Sludge 17 Incinerators 17 Solid Waste 18 Oily Bilge 19 Patchwork of Regulations and the Clean Cruise Ship Act 20 III. Medical Care and Illness 22 Malpractice and Liability 23 Norovirus and Other Illness Outbreaks 25 Potable Water 26 IV. Labour Issues 27 U.S. Congressional Interest 28 U.S. Courts and Labor 29 Arbitration Clauses 30 Crew Member Work Conditions 31 Appendix A: Events at Sea 33 Appendix B: Analysis of Crime Reports Received by the FBI from Cruise Ships, 2007 – 2008 51 1 ORAL TESTIMONY It is an honor to be asked to share my knowledge and insights with the U.S. -

Composition Nord – Art Constructif Leads Christie’S Fall Sale of Latin American Art

MEDIA ALERT | N E W Y O R K | 2 NOVEMBER 2015 | FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JOAQUÍN TORRES-GARCÍA MASTERPIECE, COMPOSITION NORD – ART CONSTRUCTIF LEADS CHRISTIE’S FALL SALE OF LATIN AMERICAN ART Joaquín Torres-García (1874-1949), Composition Nord - Art Constructif, 1931. $1,500,000-2,000,000 Auction: November 20, 7 pm, Christie’s Rockefeller Center (Day Sale: November 21, 2 pm) Exhibition: November 14 – 19 New York – Christie’s is pleased to present a modern masterpiece by Joaquín Torres-García from the artist’s most sought after period in the fall Latin American Art Evening Sale in New York on November 20. Making its first appearance at auction, Composition Nord - Art Constructif (pictured above, estimate $1,500,000 - 2,000,000), has been in the same private European collection for the past 55 years. It has been exhibited occasionally in prominent exhibitions and biennials, including the Venice Biennale XXVII in 1956 and the Bienal de São Paulo in 1959, as well as at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa in 1970. The artist is currently the focus of a major retrospective exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, on view through mid-February 2016. Created while the artist lived in Paris at the height of his career, Composition Nord (oil on board laid on Masonite, 31 ¼ x 23 5/8 in, signed and dated ’31) serves as a virtual blueprint for understanding Torres- García’s theory of “Universal Constructivism,” his idiosyncratic vision of art. Following stints in New York, Italy, and southern France, Torres-García moved to Paris in September 1926 and quickly gravitated toward a group of artists exploring paths within geometric abstraction—among them, Piet Mondrian, Georges Vantongerloo, and Theo van Doesburg. -

Studies of Cultural Pluralism by Connecticut High School Students. the Peoples of Connecticut Multicultural Ethnic Heritage Series

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 216 966 SO 014 067 AUTHOR Stone, Frank Andrews, Ed. TITLE Studies of Cultural Pluralism by Connecticut High School Students. The Peoples of Connecticut Multicultural Ethnic Heritage Series. INSTITUTION Connecticut Univ., Storrs. Thut (I.N.) World Education Center. REPORT NO ISBN-0-918158-20 PUB DATE 81 NOTE 70p.; Photographs may not reproduce clearly. AVAILABLE FROM I.N. Thut World Education Center, Box U-32, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT 06268. EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Cultural Awareness; *Cultural Pluz'alism; Essays; Ethnicity; *Ethnic Studies; High Schools; Local History; *Multicultural Education; Oral History; Photography; *State History; Student Developed Matf,rials IDENTIFIERS *Connecticut ABSTRACT The ten essays that comprise this anthology_ concerning the people of Connecticut were written by high school students in Connecticut for the First Ethnic Studies Competitionheld in 1979-1980. The aim of the competition was to increase awareness of cultural pluralism in the state, to encourage multicultural education, to improve intergroup understanding among citizens, and to expand the available multicultural resources about similarities and differences in Connecticut ethnicity. Twenty five manuscripts were entered in the competition in three categories: oral histories,local histories, and photographic studies. These entries were judged on tore basis of six criteria: general appearance, the accuracy of their contents, the insights that they provide into lifeexperiences, their format and development, the depth of cross-cultural understanding that was demonstrated, and the choice of the sources employed. Winningessays included in the anthology are: "Natividade Cunha -- PS Luso-Americem in New Haven, Connecticut;" "A Struggle for Identity -- A Case Study of Ukrainians;" "A Journey to a New Life;" "BobMikulka. -

Rock Art of Latin America & the Caribbean

World Heritage Convention ROCK ART OF LATIN AMERICA & THE CARIBBEAN Thematic study June 2006 49-51 rue de la Fédération – 75015 Paris Tel +33 (0)1 45 67 67 70 – Fax +33 (0)1 45 66 06 22 www.icomos.org – [email protected] THEMATIC STUDY OF ROCK ART: LATIN AMERICA & THE CARIBBEAN ÉTUDE THÉMATIQUE DE L’ART RUPESTRE : AMÉRIQUE LATINE ET LES CARAÏBES Foreword Avant-propos ICOMOS Regional Thematic Studies on Études thématiques régionales de l’art Rock Art rupestre par l’ICOMOS ICOMOS is preparing a series of Regional L’ICOMOS prépare une série d’études Thematic Studies on Rock Art of which Latin thématiques régionales de l’art rupestre, dont America and the Caribbean is the first. These la première porte sur la région Amérique latine will amass data on regional characteristics in et Caraïbes. Ces études accumuleront des order to begin to link more strongly rock art données sur les caractéristiques régionales de images to social and economic circumstances, manière à préciser les liens qui existent entre and strong regional or local traits, particularly les images de l’art rupestre, les conditions religious or cultural traditions and beliefs. sociales et économiques et les caractéristiques régionales ou locales marquées, en particulier Rock art needs to be anchored as far as les croyances et les traditions religieuses et possible in a geo-cultural context. Its images culturelles. may be outstanding from an aesthetic point of view: more often their full significance is L’art rupestre doit être replacé autant que related to their links with the societies that possible dans son contexte géoculturel. -

School of Art 2015–2016

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Art 2015–2016 School of Art 2015–2016 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 111 Number 1 May 15, 2015 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 111 Number 1 May 15, 2015 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a protected veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Go≠-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and protected veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valarie Stanley, Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 3rd Floor, 203.432.0849. -

Exhibition: Fire Under the Ashes. from Picasso to Basquiat 5

Exhibition: Fire under the Ashes. From Picasso to Basquiat 5 May – 28 August 2005 Organized by: Institut Valencià d’Art Modern IVAM Curator: Kosme de Barañano ________________ The exhibition is based on the review of primitive art, or children’s art, carried out by numerous artists since Surrealism, which shaped the iconography of avant-garde art, both in Europe and in America, with respect to the human figure, the face and graffiti, in Constructivism, Art Brut, Informalism and the legacy of Abstract Expressionism. The selection of works in the exhibition traces the evolution and development of that imagery – that fire – in modern art through the work of such acclaimed artists as Jean Dubuffet, Michel Haas, Germaine Richier, Gaston Chaissac, Pablo Picasso, Joaquín Torres-García and Jean-Michel Basquiat. To accompany the show, the IVAM has published a catalogue, illustrated with colour reproductions of the items exhibited, together with texts by the curator of the exhibition, Kosme de Barañano, and the poets Jaime Siles and Guillermo Carnero. The title of the exhibition comes from some words quoted by Jan Krugier when recalling a visit to Rothko: “Rothko struck me as having something shamanistic about him – there was a truth in him that he had to express. I remember going to see him once 1 late at night in his studio in New York. And while I was looking at his paintings, he came out with a phrase that really struck me: ‘If you are looking for fire, you will find it beneath the ashes.’ Fashionable painters aren’t looking for fire. -

Krannert Art Museum

70-?. / Bulletin Cop- <P Krannert Art Museum University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Volume IV, Numberl, 1978 THE LIBRARY OF. TUB OCT 3683 Mailing Address Krannert Art Museum 500 Peabody Drive Champaign. Illinois 61820 Museum Gallery Hours: Monday through Saturday, 9:00 a.m. - 4:00 p.m.; Sunday 2:00 5:00 p.m. Admission free. Closed on National Holidays. Reservations: Those desiring guided group visits may make reservations by writing or calling the Krannert Art Museum, 500 Peabody Drive, University of Illinois, Champaign 61820 (telephone: area code 217/ 333-1860). Cover. Punch Bowl, details. French, Sevres. 1770. soft paste porcelain with bleu celeste glaze. 13-3/8" diam. (33.97 cm.), Gift of Mr. Harlan E. Moore. 1976. 76-5-1. Tentative Exhibition Schedule Krannert Art Museum 1978-1979 Academic Year University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign August 27-October 1 Atelier 17; Retrospective A selection of over 100 prints by 68 artists commemorates the 50th anniversary of the famous workshop, Atelier 17, founded by Stanley William Hayter in Paris in 1927. The transfer of the workshop to New York in the 1940's and back to Paris in the 1950's is traced by the production which includes a number of prints by Hayter and by artists such as Alechinsky, Calder, Kandinsky, Lasansky, Masson, Nevelson, and Tanguy who worked at Atelier 17. The exhibition was assembled by the Elvehjem Art Center at the University of Wisconsin-IVIadison; the Guest Curator was Dr. Joann tvloser of the University of Iowa Museum of Art. August 27-October 1 Photographs of the American Wilderness by Dean Brown Seventy-five photographs, 60 in color and 15 black and white, record Dean Brown's love of the wilderness. -

Primitivism and Identity in Latin America: the Appropriation Of

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Art History Honors Papers Art History and Architectural Studies 2015 Primitivism and Identity in Latin America: The Appropriation of Indigenous Cultures in 20th- Century Latin American Art Rachel Newman Connecticut College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/arthisthp Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Newman, Rachel, "Primitivism and Identity in Latin America: The Appropriation of Indigenous Cultures in 20th-Century Latin American Art" (2015). Art History Honors Papers. 3. http://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/arthisthp/3 This Honors Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History and Architectural Studies at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. Primitivism and Identity in Latin America The Appropriation of Indigenous Cultures in 20th-Century Latin American Art An Honors Thesis presented by Rachel Beth Newman to The Department of Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major Field Connecticut College New London, Connecticut May 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to give my sincere thanks to the many professors, colleagues, and staff who have been a part of my college career. I thank you for your assistance, advice, and support. To Professor Steiner, my first reader, museum studies guru, and event planner extraordinaire who supported, encouraged, and guided me through this process and senior year. -

Abstract Arts

2019 Frieze Masters | Booth D14 Regent’s Park, London Preview 02 - 03 Oct 2019 Public viewing 04-06 Oct 2019 2000 Years of Abstract Arts At Frieze Masters (London) 2019, Paul Hughes Fine Arts will exhibit a museum quality collection of lavish Andean Pre-Co- lumbian feather and woven textiles spanning from 100BC to 1200AD, these feather works will be juxtaposed with the works of Bauhaus legend Max Bill, the student of Josef Albers, to engage the viewers in the continuing legacy that these astounding feather pieces had on two of the 20th century most compelling and inventive artists. Further more, we will present an important work of the South American modernist maestro Joaquín Torres García to introduce the modern art history of South American that is firmly rooted in their own Pre-Columbian past. Inca loincloth c.1400 AD Inca culture, Southern Andes Camelid fibres 140 x 98 cm Feather Tunic, Huari Culture, circa 800 AD, 20 x 38 cm Feather tunic, c.800 AD Huari culture Southern Andes Feathers and camelid fibres 200 x 145 cm Andean Pre-Columbian Textiles are one of the seminal yet little-known influences to a Pan-American prototype of abstraction in the pre and post-war era. Along with innovative art schools such as the Bauhaus, Black Mountain College and Tallier Torres-García, prestigious museums collections such as the Rockefellers’ in the Museum of Primitive Art, and dealers such as Betty Parsons and Andre Emmerich, these cross-fertilisations of visual arts cultures are explored extensively, and have since influenced several generations of European and American artists.