WINE VALUE CHAINS: CHALLENGES and PROSPECTS Anatoliy G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

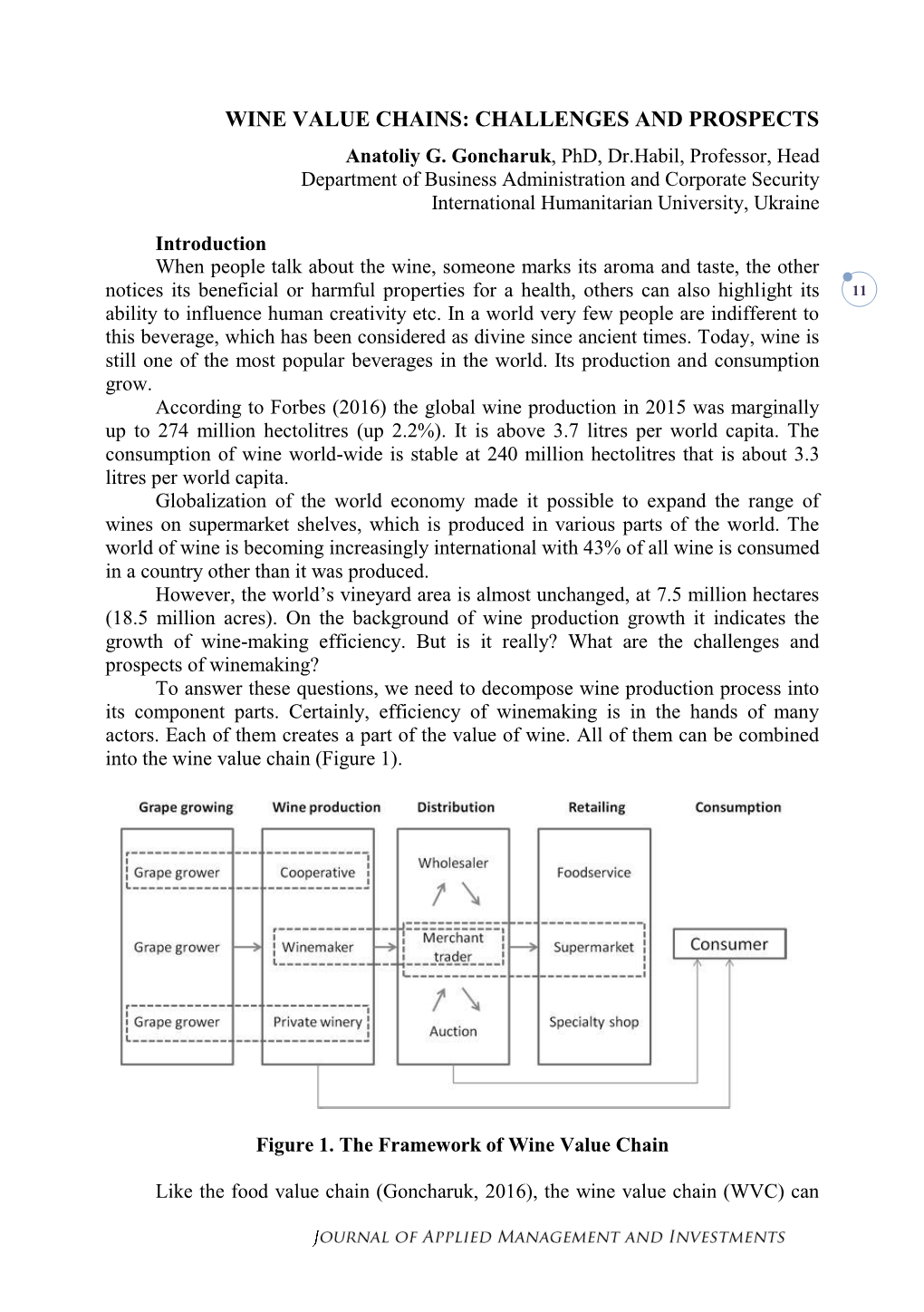

-

''The Only Fault of Wine Is That There Is Always a Lack of Wine''

Ukrainian WineHub #1 at Eastern 2020 Europe rinks market! page 7 clockOnline Newspaper: Eastern news and Western trends www.drinks.uaD Christian ‘‘The only fault Wolf: ‘MUNDUS VINI feels like Oa family’ of is that wine page14 there is always a lack of wine’’ Legend of Ukraine is not Georgia, that’s true. Yes, this country is not Saracena: a cradle of wine and cannot boast of its 8-thousand-year Drink less, read more! a unique peerless history. And the history recorded in the annals is just as sad ancient dessert wine as the history of the entire Ukrainian nation: “perestroika”, a row of economic crises, criminalization of the alcohol sector. page 32 The last straw was the occupation of Crimea by Russia and the loss of production sites and unique vineyards, including autochthonous varieties. Nevertheless, the industry is alive. It produces millions of decalitres, and even showed a Steven revival in the last year. At least on a moral level t. Spurrier: Continued on page 9 “The real Judgement of Paris movie was never made” page 21 2 rinks Dclock By the glass O Azerbaijan Wines from decline to a revival The production of Azerbaijani winemakers may be compared to the Phoenix bird. Just like this mythological creature, in the 21st century, Azerbaijani wine begins to revive after almost a complete decline in the 90s, when over 130 thousand hectares of vineyards were cut out in the country not only with technical varieties but which also opens up an incredibly also with unique table varieties. vast field of activity for crossing the As a new century set in, they Pan-Caucasian and local variet- managed to breathe a new life ies. -

A Structural Analysis of the Armenian Wine Industry

Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen Hochschule Geisenheim University Master-Thesis ‘A structural analysis of the Armenian Wine Industry: Elaboration of strategies for the domestic market’ Reviewer: Prof. Dr. habil. Jon H. Hanf Department of Wine and Beverage Business, Geisenheim Univer- sity Co-Reviewer: Prof. Dr. Rainer Kühl Institute for Agribusiness and Food Economics, Justus-Liebig- University Gießen Written by: B.Sc. Linda Bitsch Worms-Pfiffligheim, 03.04.2017 LIST OF CONTENTS LIST OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................. II LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................ III LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................... IV LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................ V 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 1 1.1 OBJECTIVE ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 APPROACH AND STRUCTURE ................................................................................. 2 2 ARMENIA ............................................................................................................... 4 2.1 AGRICULTURAL SECTOR AND THE TRANSFORMATION PROCESS ........................... 4 2.2 ARMENIAN WINE INDUSTRY ................................................................................. -

OIV in the News Other Articles EN Other Articles ES

Agenda OIV News - 1/02/2017 ©Jon Wyand « Une année en Corton » Editions Glénat 40th World Congress of Vine and Wine Call for papers Convocatoria para el envío de trabajos Appel à communications Invito a presentare i contributi scientifici Aufruf zur Einreichung von Beiträgen http://www.oiv.int/en/oiv-life/2017-congressnbsp OIV in the news Azerbaijani wine enters new markets TopNews Viorica, and Kishmish Moldavski. Azerbaijan became a member of the International Organisation of Vine and Wine in June 2014. The country has... Les vendanges mondiales au plus bas depuis 20 ans Irrigazette ...depuis vingt ans. Selon l'Organisation internationale du vin et de la vigne (OIV) les 7,5 259 millions d'hectolitres de vin ont été produits en... Other articles EN Are we ready for genetically modified wine? wine.co.za A number of studies are underway to introduce new traits in wine grapes through GMO techniques South Africa's grape harvest affected by drought Nam News Network Experts in South Africa's wine industry say the ongoing drought has had a dramatic effect on the size and volume of grapes this season. Other Articles ES Casi el 50% de las reservas de enoturismo se realizan por Internet Vinetur La comercialización de enoturismo pasa por Internet. Amorim lanza los primeros corchos naturales del mundo con TCA no detectable La Prensa del Rioja Amorim ha abierto una importante brecha tecnológica convirtiéndose en el primer y único proveedor de corcho natural a nivel mundial que garantiza la ausencia de TCA detectable. Other articles FR Costières de Nîmes : deux dénominations complémentaires d’ici 2019 ? mon-Viti L’appellation Costières de Nîmes vient de déposer un dossier auprès de l'INAO afin de demander la reconnaissance de deux dénominations géographiques complémentaires à l'appellation : Franquevaux et Saint-Roman. -

Тимур Гареев, Генеральный Директор «СУШИСЕТ»: «ОТКРОЙ СУШИСЕТ И ПОЛУЧАЙ ПРИБЫЛЬ С ПЕРВОГО ГОДА РАБОТЫ!» 52 ��+7 (495) 730-09-19 ��[email protected] КАЛИБР Коворкинг

51 30/121QUALITY декабрь INDEX 2020 With the support of the CCI of Russia 12+ ГЕННАДИЙ РЕГИОН ЛАМШИН: НОМЕРА: !ТО, ЧТО БЫЛО В ГОСТИНИЧНОМ ИРКУТСК БИЗНЕСЕ ДО СОЗДАНИЯ НАШЕЙ АССОЦИАЦИИ, НЕ МОГЛО УДОВЛЕТВОРЯТЬ НИКОГО В ЭТОЙ СФЕРЕ< ИГОРЬ КОБЗЕВ, !САВАЛАН<: ГУБЕРНАТОР ЛОЗА, ИРКУТСКОЙ СВЯЗАВШАЯ ОБЛАСТИ: ТЫСЯЧЕЛЕТИЯ «ПОВЫШЕНИЕ КАЧЕСТВА ЖИЗНИ В КРАЕ – НАША ГЛАВНАЯ ЦЕЛЬ!» Тимур Гареев, генеральный директор «СУШИСЕТ»: «ОТКРОЙ СУШИСЕТ И ПОЛУЧАЙ ПРИБЫЛЬ С ПЕРВОГО ГОДА РАБОТЫ!» 52 +7 (495) 730-09-19 [email protected] КАЛИБР коворкинг РАБОЧИЕ ПРОСТРАНСТВА ПОД ЛЮБОЙ КАЛИБР RUSSIAN BUSINESS GUIDE !ДЕКАБРЬ 2020) реклама CONTENTS | СОДЕРЖАНИЕ 1 Russian Business Guide ОФИЦИАЛЬНО | OFFICIALLY www.rbgmedia.ru Деловое издание, рассказывающее о развитии, отраслях, перспективах, персоналиях бизнеса в ГЕННАДИЙ ЛАМШИН: 5ТО, ЧТО БЫЛО В ГОСТИНИЧНОМ БИЗНЕСЕ ДО СОЗДАНИЯ России и за рубежом. НАШЕЙ АССОЦИАЦИИ, НЕ МОГЛО УДОВЛЕТВОРЯТЬ НИКОГО В ЭТОЙ СФЕРЕ< 12+ 2 GENNADY LAMSHIN: “THE SITUATION THAT EXISTED IN THE HOTEL BUSINESS BEFORE OUR Учредитель и издатель: ASSOCIATION WAS ESTABLISHED COULD SATISFY NOBODY IN THIS AREA” ООО «БИЗНЕС-ДИАЛОГ МЕДИА» при поддержке ТПП РФ Редакционная группа: Максим Фатеев, Вадим Винокуров, Наталья Чернышова Главный редактор: ЛИЦО С ОБЛОЖКИ | COVER STORY Мария Сергеевна Суворовская Редактор номера: София Антоновна Коршунова ТИМУР ГАРЕЕВ, 5СУШИСЕТ<: 5ПРЕПЯТСТВИЯ НАС ДОПОЛНИТЕЛЬНО МОТИВИРУЮТ!< Заместитель директора по коммерческим вопросам: TIMUR GAREEV, SUSHISET: “CHALLENGES MOTIVATE US!” Ирина Владимировна Длугач 6 Дизайн/вёрстка: Александр Лобов Перевод: Мария Ключко Отпечатано в типографии ООО «ВИВА-СТАР», г. Москва, ул. Электрозаводская, д. 20, стр. 3. Материалы, отмеченные значком R или «РЕКЛАМА», публикуются на правах рекламы. Мнение авторов ИНДЕКС КАЧЕСТВА | QUALITY INDEX не обязательно должно совпадать с мнением редакции. Перепечатка материалов и их использование в любой форме 5САВАЛАН<: ЛОЗА, СВЯЗАВШАЯ ТЫСЯЧЕЛЕТИЯ допускается только с разрешения редакции SAVALAN: THE VINE WHICH BOUND THE MILLENNIA издания «Бизнес-Диалог Медиа». -

The Role of Vine and Wine Foundation of Armenia in Wine Tourism Development

The role of Vine and Wine Foundation of Armenia in wine tourism development Hayarpi Shahinyan Executive Assistant, Vine and Wine Foundation of Armenia Yerevan 2018 Establishment of VWFA • Government of Armenia recognized the production of wine and brandy as priority sector of economy. • With the aim of introducing a new strategy for state policy and development programs, Vine and Wine Foundation of Armenia was established in 2016. • Founder is the Government of Armenia and the state authorized body is the Ministry of Agriculture. The prime objective of VWFA to preserve and develop the rich cultural and historical heritage of Armenian wine in Armenia and around the world. The objectives of VWFA • to develop viticulture as a guarantee of a high-quality wine production, • to improve quality of wine production, • to raise winemaking reputation and competitiveness of the country, • to develop Armenian wine culture, • to create and promote "Wines of Armenia" brand, • to promote export of wine, • to promote wine consumption culture in Armenia. The framework of activities • Viticulture projects • Wine projects • Wine education • Wine law • Wine marketing • Wine tourism Wine Tourism Projects Wine Tourism Development Activities: Supporting home-made wine producers to improve the quality of wine and entry to market, Supporting organization of wine festivals: Areni Wine Festival (more than 1000 visitors), Raising awareness within population through various events (tastings, master classes, TV programs). Wine Education Enhancement of professional -

Armenian Monuments Awareness Project

Armenian Monuments Awareness Project Armenian Monuments Awareness Project he Armenian Monuments Awareness Proj- ect fulfills a dream shared by a 12-person team that includes 10 local Armenians who make up our Non Governmental Organi- zation. Simply: We want to make the Ar- T menia we’ve come to love accessible to visitors and Armenian locals alike. Until AMAP began making installations of its infor- Monuments mation panels, there remained little on-site mate- rial at monuments. Limited information was typi- Awareness cally poorly displayed and most often inaccessible to visitors who spoke neither Russian nor Armenian. Bagratashen Project Over the past two years AMAP has been steadily Akhtala and aggressively upgrading the visitor experience Haghpat for local visitors as well as the growing thousands Sanahin Odzun of foreign tourists. Guests to Armenia’s popular his- Kobair toric and cultural destinations can now find large and artistically designed panels with significant information in five languages (Armenian, Russian, Gyumri Fioletovo Aghavnavank English, French, Italian). Information is also avail- Goshavank able in another six languages on laminated hand- Dilijan outs. Further, AMAP has put up color-coded direc- Sevanavank tional road signs directing drivers to the sites. Lchashen Norashen In 2009 we have produced more than 380 sources Noratuz of information, including panels, directional signs Amberd and placards at more than 40 locations nation- wide. Our Green Monuments campaign has plant- Lichk Gegard ed more than 400 trees and -

The Prospects for Wine Tourism As a Tool for Rural Development in Armenia – the Case of Vayots Dzor Marz1

The Prospetcs for Wine Tourism as a Tool for ... _________________________________________________________________________ Прегледни рад Економика пољопривреде Број 4/2011. УДК: 338.48-6:642(470.62/.67) THE PROSPECTS FOR WINE TOURISM AS A TOOL FOR RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN ARMENIA – THE CASE OF VAYOTS DZOR MARZ1 A. Harutjunjan2, Margaret Loseby3 Abstract. The paper examines the prospective role which wine tourism could play in the rural and in the much needed overall economic development of Armenia. It begins with a brief description of the antique origin and the present economic situation of the wine sector in Armenia, followed by a description of recent trends in the tourist sector as a whole in Armenia. The particular features of wine tourism are examined in relation to Armenia and to other wine producing countries. Attention is then concentrated on a specific region of Armenia, Vayots Dzor, which is particularly important for wine production, and is also endowed with historical monuments with great potential for the development of tourism. The case of one particular village is illustrated in some detail in order to indicate how tourism in general, and specifically wine tourism could be developed for the benefit of the rural community. The paper concludes by outlining a strategy to be followed to achieve the growth of the sector. Key words: Wine industry, tourism, cultural heritage, rural development, wine tourism 1. Introduction Grape cultivation is believed to have originated in Armenia near the Caspian Sea, from where it seems to have spread westward to Europe and Eastward to Iran and Afghanistan (Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific 1999). -

Agriculture and Food Processing in Armenia

SAMVEL AVETISYAN AGRICULTURE AND FOOD PROCESSING IN ARMENIA YEREVAN 2010 Dedicated to the memory of the author’s son, Sergey Avetisyan Approved for publication by the Scientifi c and Technical Council of the RA Ministry of Agriculture Peer Reviewers: Doctor of Economics, Prof. Ashot Bayadyan Candidate Doctor of Economics, Docent Sergey Meloyan Technical Editor: Doctor of Economics Hrachya Tspnetsyan Samvel S. Avetisyan Agriculture and Food Processing in Armenia – Limush Publishing House, Yerevan 2010 - 138 pages Photos courtesy CARD, Zaven Khachikyan, Hambardzum Hovhannisyan This book presents the current state and development opportunities of the Armenian agriculture. Special importance has been attached to the potential of agriculture, the agricultural reform process, accomplishments and problems. The author brings up particular facts in combination with historic data. Brief information is offered on leading agricultural and processing enterprises. The book can be a useful source for people interested in the agrarian sector of Armenia, specialists, and students. Publication of this book is made possible by the generous fi nancial support of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and assistance of the “Center for Agribusiness and Rural Development” Foundation. The contents do not necessarily represent the views of USDA, the U.S. Government or “Center for Agribusiness and Rural Development” Foundation. INTRODUCTION Food and Agriculture sector is one of the most important industries in Armenia’s economy. The role of the agrarian sector has been critical from the perspectives of the country’s economic development, food safety, and overcoming rural poverty. It is remarkable that still prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, Armenia made unprecedented steps towards agrarian reforms. -

Turkish Delights: Stunning Regional Recipes from the Bosphorus to the Black Sea Pdf

FREE TURKISH DELIGHTS: STUNNING REGIONAL RECIPES FROM THE BOSPHORUS TO THE BLACK SEA PDF John Gregory-Smith | 240 pages | 12 Oct 2015 | Kyle Books | 9780857832986 | English | London, United Kingdom Turkish Delights: Stunning Regional Recipes from the Bosphorus to the Black Sea | Eat Your Books She hopes these recipes will take you on a Turkish journey - to learn, taste and enjoy the delicious foods of her homeland and most importantly to feel the warmth and sharing spirit of Turkish culture. Turkish cuisine is based on seasonal fresh produce. It is healthy, delicious, affordable and easy to make. She shows you how to recreate these wonderful recipes in your own home, wherever you are in the world. Her dishes are flavoured naturally with: olive oil, lemon juice, nuts, spices, as well as condiments like pomegranate molasses and nar eksisi. Turkish cuisine also offers plenty of options for vegetarian, gluten-free and vegan diets. She hopes her recipes inspire you to recreate them in your own kitchen and that they can bring you fond memories of your time in Turkey or any special moments shared with loved ones. Her roots - Ancient Antioch, Antakya Her family's roots date back to ancient Antioch, Antakya, located in the southern part of Turkey, near the Syrian border. This book is a special tribute to Antakya and southern Turkish cuisine, as her cooking has been inspired by this special land. Her parents, Orhan and Gulcin, were both born in Antakya and she spent many happy childhood holidays in this ancient city, playing in the courtyard of her grandmother's year old stone home, under the fig and walnut trees. -

Azerbaijani Grapes: Past and Present Famil Sharifov Ph.D

Focusing on Azerbaijan Azerbaijani grapes: Past and Present Famil SHARIFOV Ph.D. in Agriculture WHITE SHANI Local Absheron variety AZERBAIJAN IS AN ANCIENT LAND OF VITICULTURE. Its NatURE AND CLimatE ARE FAVORABLE FOR GROWING DIFFERENT VARIETIES OF GRAPES. THE OLDEst, LONG-stORED, SUGARY AND HIGH-YIELDING VARIETIES HAVE ALWAYS BEEN CULTI- VatED IN OUR COUNTRY. zerbaijani grapes and prod- in particular, is considered one of Archeological excavations are an ucts made of them, such as the centers of plants, including effective tool for studying the socio- Agrape juices which make you grapes. economic background of Azerbai- physically vigorous and sherbets According to Nizami’s works, jani people, including the history with their scent of flowers that are when the troops of Alexander the of viticulture. There is extensive ar- also a source of high spirits, have Great invaded Azerbaijan and be- cheological information suggest- been served for holiday feasts since sieged Barda, according to an ar- ing that the peoples inhabiting the ancient times. rangement with local ruler Nushaba, territory of present-day Azerbaijan Azerbaijan’s natural conditions part of the local population’s tribute had developed viticulture. Some are conducive to growing grapes. was paid in grapes. buried grape clusters have reached Even primitive man, in addition to Wine is also mentioned on the us from the depth of centuries in a hunting and fishing, gathered wild- lists of products exacted in tax from dry and semi-decomposed condi- growing berries and fruit, including the people of north-western Media. tion. Quite a few of the surviving grapes. According to a research In 714 B.C., during the arrival of Sar- grapes had been placed in jugs and by prominent Russian botanist N. -

Unearth the Flavours with Delightful Wines

şərəfə cheers Contents: fabulous vineyards Ganja-Gazakh cultivated connoisseurs 2 and the Lesser Caucasus 27 Azerbaijan, an ancient cradle of viniculture, is once wine history different tastes again coming of age. Beautifully balanced wines are in Azerbaijan 4 unique experiences 34 made with love from grapes grown on Caucasian slopes, grape unearth the flavours soaked in sunshine and soothed by Caspian breezes. types 7 with delightful wines 36 Come... Taste... Delight... wine regions wine bars of Azerbaijan 8 in Baku 40 Caspian salam shoreline 11 Azerbaijan 44 Shirvan useful wine and the Caucasian foothills 17 vocabulary 45 WINEMAKING IN AZERBAIJAN fabulous vineyards cultivated connoisseurs Azerbaijan is a country of fascinating surprises. The Wineries & Wine Tours st dazzling 21 -century architecture of Baku. The glitzy While some families do make their other non-grape wines, most notably ski resorts of Shahdag and Tufandag. The Silk Route own wines – notably in the culturally full-flavoured pomegranate wines which unique village of Ivanovka or in the are a current favourite amongst Baku’s gem-city of Sheki... And, yes, the wonderful wine. Gazakh region – most of Azerbaijan’s younger social circles and tourists visiting production comes from larger our country. The best-known versions companies with access to a wide are made by Az-Granata (Agsu) and Azerbaijan is very proudly a secular, Azerbaijan’s wine industry has variety of vineyards. This provides the Tovuz-Baltiya (Tovuz), which can also be multicultural country, a place of been expanding rapidly over the last conditions for a similarly wide variety of tasted during the traditional Goychay passionate Caucasian spirit, and one decade with extensive investments in grape types to be grown which in turn Pomegranate Festival held every year in of the cradles of world viticulture. -

Consumption in Armenia – an Analysis of the Wine Demand

Hochschule Geisenheim University Bachelor-Thesis Consumption in Armenia – An Analysis of the Wine Demand Reviewer : Prof. Dr. habil. Jon Hanf Department of Wine and Beverage Business Geisenheim University Co-Reviewer: M.Sc. Linda Bitsch Department of Wine and Beverage Business Geisenheim University Written by : Anne Elisabeth Hugger 7th Semester Bahnstraße 1 65366 Geisenheim Geisenheim, 21.12.2018 Affidavit Eidesstattliche Erklärung Hiermit erkläre ich an Eides Statt, dass ich die vorliegende Bachelor-Thesis "Consumption in Armenia – An Anlysis of the Wine Demand“ selbständig und ohne fremde Hilfe angefertigt habe. Ich habe dabei nur die in der Arbeit angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel benutzt. Geisenheim, 21.12. 2018 Table of Content 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 6 2 Consumption ....................................................................................................................... 8 Consumption Theory .................................................................................................. 8 SOR-Model .......................................................................................................... 8 2.1.1.1 Stimuli ............................................................................................................. 10 2.1.1.2 Consumer ...................................................................................................... 10 External Factors .......................................................................................................