Experience Won't Always Save

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Airport City Developments in Australia : Land Use Classification and Analyses

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Queensland University of Technology ePrints Archive QUT Digital Repository: http://eprints.qut.edu.au/ Walker, Arron R. and Stevens, Nicholas J. (2008) Airport city developments in Australia : land use classification and analyses. In: 10th TRAIL Congress and Knowledge Market, 14-15 October 2008, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. © Copyright 2008 [please consult the authors] Airport city developments in Australia Land use classification and analyses TRAIL Research School, Delft, October 2008 Authors Dr. Arron Walker, Dr. Nicholas Stevens Faculty of Built Environment and Engineering, School of Urban Development, Queensland University of Technology, Qld, Australia © 2008 by A. Walker, N. Stevens and TRAIL Research School Contents Abstract 1 Introduction.......................................................................................................1 2 Background........................................................................................................2 2.1 Aviation growth in Australia...............................................................................2 2.2 Airport ownership in Australia ...........................................................................3 2.3 Airport Planning under Airports Act 1996 .........................................................4 2.4 Diversification of airport revenue.......................................................................5 3 Land use analysis: methods and materials .....................................................5 -

Loss of Control, Clyde North, Vic., 23 February 2007, Van's Aircraft Inc

ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT Aviation Occurrence Investigation – 200701033 Final Loss of Control Clyde North, Victoria 23 February 2007 Van’s Aircraft Inc. RV-4, VH-ZGH ATSB TRANSPORT SAFETY INVESTIGATION REPORT Aviation Occurrence Investigation 200701033 Final Loss of Control Clyde North, Victoria 23 February 2007 Van’s Aircraft Inc. RV-4, VH-ZGH Released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 - i - Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office location: 15 Mort Street, Canberra City, Australian Capital Territory Telephone: 1800 621 372; from overseas + 61 2 6274 6440 Accident and incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6247 3117; from overseas + 61 2 6247 3117 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2008. This work is copyright. In the interests of enhancing the value of the information contained in this publication you may copy, download, display, print, reproduce and distribute this material in unaltered form (retaining this notice). However, copyright in the material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. Where you want to use their material you will need to contact them directly. Subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968, you must not make any other use of the material in this publication unless you have the permission of the Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Please direct requests for further information or authorisation to: Commonwealth Copyright Administration, Copyright Law Branch Attorney-General’s Department, Robert Garran Offices, National Circuit, Barton ACT 2600 www.ag.gov.au/cca ISBN and formal report title: see ‘Document retrieval information’ on page iii. -

VFR Flight Into Dark Night Conditions and Loss of Control Involving Piper PA-28-180, VH-POJ

VFR flight into dark night Insertconditions document and loss titleof control involving Piper PA-28-180, VH-POJ Location31 km north | Date of Horsham Airport, Victoria | 15 August 2011 ATSB Transport Safety Report Investigation [InsertAviation Mode] Occurrence Occurrence Investigation Investigation XX-YYYY-####AO -2011-10 0 Final – 3 December 2013 Released in accordance with section 25 of the Transport Safety Investigation Act 2003 Publishing information Published by: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Postal address: PO Box 967, Civic Square ACT 2608 Office: 62 Northbourne Avenue Canberra, Australian Capital Territory 2601 Telephone: 1800 020 616, from overseas +61 2 6257 4150 (24 hours) Accident and incident notification: 1800 011 034 (24 hours) Facsimile: 02 6247 3117, from overseas +61 2 6247 3117 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.atsb.gov.au © Commonwealth of Australia 2013 Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia. Creative Commons licence With the exception of the Coat of Arms, ATSB logo, and photos and graphics in which a third party holds copyright, this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form license agreement that allows you to copy, distribute, transmit and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work. The ATSB’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourced from it) using the following wording: Source: Australian Transport Safety Bureau Copyright in material obtained from other agencies, private individuals or organisations, belongs to those agencies, individuals or organisations. -

Essendon Fields Precinct – Hyatt Place Melbourne

insert cover positional here MELBOURNE CBD about this 15 minutes box size 10% Transparency of your 16 DFO ESSENDON cover artwork Tullamarine Freeway & CityLink TRA N S P O R T A BOUT U S 15 iFLY THINGS TO D O F OOD & DRINK 6 ESSENDON FIELDS AIRPORT 7 GYMNASIUM S ERVICE S 9 ESSENDON FIELDS CENTRAL 12 LAMANNA CAFÉ & SUPERMARKET ue ven 1 THE HUNGRY FOX CAFÉ ve A Hargra Bristol Street 2 CAR DEALERSHIPS MELBOURNE AIRPORT 3 FLIGHT EXPERIENCES 8 CHILDCARE 11 DENTIST 7km* 4 AIRWAYS MUSEUM 13 HYATT PLACE HOTEL & EVENTS CENTRE CYCLING TRAIL 5 BOUNCE INC. TRAM STOP 56 10 MEDICAL CENTRE English Street ESSENDON STATION oad Nomad R levard kin Bou Lar ESSENDON FIELDS IS WELL CONNECTED TO BOTH THE BUSINESS DISTRICT MELBOURNE CBD AND 14 MR MCCRACKEN RESTAURANT & BAR MELBOURNE AIRPORT MELBOURNE CBD 10km* Public Transport The free EF Station Shuttle operates from Essendon Fields to Essendon Train Station. Every weekday departing on the half hour between 7.15 – 9.30am & 4.15 – 6.30pm. Tram service 59 is a short walk from EF. Stop 56 (Airport West), located on Matthews Ave/ Earl Street departs every 8 minutes. Myki available from EF Newsagency. Airport Transit 16 DFO Essendon The free airport shuttle bus operates on- DFO Essendon comprises over 110 outlet retailers including demand daily between Essendon Fields Polo Ralph Lauren, Hugo Boss, Ted Baker and Coach. The Airport and Melbourne Airport between adjacent Homemaker Hub comprises over 20 stores. 6.00am and 10.00pm. Visit ef.com.au/ 100 Bulla Road, Essendon airportshuttle for booking details. -

TTF Rapid Buses, Road & Rail (Melbourne Airport)

RAPID BUSES, ROAD AND RAIL GROUND TRANSPORT SOLUTIONS TO MEET MELBOURNE AIRPORT’S PASSENGER GROWTH TO 2050 JULY 2013 Membership of Tourism & Transport Forum Tourism & Transport Forum (TTF) is a national, member-funded CEO forum, advocating the public policy interests of 200 leading corporations and institutions in the Australian tourism, transport, aviation and investment sectors For further information please contact: Justin Wastnage | Director, Aviation Policy | [email protected] Martin Gray | Policy Officer |[email protected] Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... 4 Ensuring transport choice for Melbourne Airport ................................................................ 4 SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................... 6 List of figures ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 MELBOURNE AIRPORT – THE NEXT 30 YEARS ............................................................ 7 Forecast demand .................................................................................................................... 7 ACCESSING MELBOURNE AIRPORT .......................................................................... 8 Internal airport transport ......................................................................................................... 8 Broader road network ............................................................................................................ -

MINUTES AAA Victorian Division Meeting

MINUTES AAA Victorian Division Meeting Tuesday 22 March 2016 10:00-15:00 Flight Deck Bar & Grill, 37 First Avenue, Moorabbin Airport, VIC 1. Welcome and Apologies Paul Ferguson (Chair) opened the meeting and welcomed members, thanking them for their attendance. A lunchtime visit to the Australian National Aviation Museum was offered to all attending members as well as a site tour of Moorabbin Airport. Attendees and apologies are listed below. ATTENDEES Paul Ferguson (Chair) Moorabbin Airport Corporation Guy Thompson AAA (National Chairman) Jared Feehely AAA Matt Smale Air BP Bryan Fitzgerald Airport Surveys Pty Ltd Kent Quigley Airservices Australia Ken Keech Australian International Airshow Chris Stocks Avdata Australia Sharon Lee Avdata Australia Bron Wiseman Avdata Australia Jeremy King Avlite Systems Pty Ltd Roger Druce Bacchus Marsh Aerodrome Management Inc. Joseph Walsh Beca Darren Angelo CASA Ron Brownlees City of Kingston Phil McConnell Cloud Aviation Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Marianne Richards Transport and Resources (DEDJTR) Ross Ioakim Downer Rory Kennedy Essendon Airport Graeme Ware Essendon Airport Daniel Taylor Fulton Hogan Nick Hrysomallis Fulton Hogan David Spencer Gannawarra Shire Brian Roberts Gannawarra Shire Ian Bell Global Safety Partners Trent Kneebush Kneebush Planning Garry Baum Lethbridge Airport MINUTES | AAA Victorian Division Meeting | Tuesday 22 March 2016 Tim Marks Marshall Day Acoustics Christophe Delaire Marshall Day Acoustics Justin Adcock Marshall Day Acoustics Melanie Hearne Melbourne -

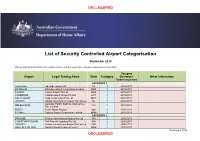

Airport Categorisation List

UNCLASSIFIED List of Security Controlled Airport Categorisation September 2018 *Please note that this table will continue to be updated upon new category approvals and gazettal Category Airport Legal Trading Name State Category Operations Other Information Commencement CATEGORY 1 ADELAIDE Adelaide Airport Ltd SA 1 22/12/2011 BRISBANE Brisbane Airport Corporation Limited QLD 1 22/12/2011 CAIRNS Cairns Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 CANBERRA Capital Airport Group Pty Ltd ACT 1 22/12/2011 GOLD COAST Gold Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 1 22/12/2011 DARWIN Darwin International Airport Pty Limited NT 1 22/12/2011 Australia Pacific Airports (Melbourne) MELBOURNE VIC 1 22/12/2011 Pty. Limited PERTH Perth Airport Pty Ltd WA 1 22/12/2011 SYDNEY Sydney Airport Corporation Limited NSW 1 22/12/2011 CATEGORY 2 BROOME Broome International Airport Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 CHRISTMAS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 HOBART Hobart International Airport Pty Limited TAS 2 29/02/2012 NORFOLK ISLAND Norfolk Island Regional Council NSW 2 22/12/2011 September 2018 UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED PORT HEDLAND PHIA Operating Company Pty Ltd WA 2 22/12/2011 SUNSHINE COAST Sunshine Coast Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 29/06/2012 TOWNSVILLE AIRPORT Townsville Airport Pty Ltd QLD 2 19/12/2014 CATEGORY 3 ALBURY Albury City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 ALICE SPRINGS Alice Springs Airport Pty Limited NT 3 11/01/2012 AVALON Avalon Airport Australia Pty Ltd VIC 3 22/12/2011 Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia NT 3 22/12/2011 AYERS ROCK Pty Ltd BALLINA Ballina Shire Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 BRISBANE WEST Brisbane West Wellcamp Airport Pty QLD 3 17/11/2014 WELLCAMP Ltd BUNDABERG Bundaberg Regional Council QLD 3 18/01/2012 CLONCURRY Cloncurry Shire Council QLD 3 29/02/2012 COCOS ISLAND Toll Remote Logistics Pty Ltd WA 3 22/12/2011 COFFS HARBOUR Coffs Harbour City Council NSW 3 22/12/2011 DEVONPORT Tasmanian Ports Corporation Pty. -

Essendon Airport Land Use Plan 2013

ESSENDON AIRPORT LAND USE PLAN Essendon Airport Land Use Plan | 119 EFOP025_MasterPlan2013_EnvironmentalStrategy_FA.indd 119 1/07/2014 9:32 am Purpose of this Land Use Plan Essendon Airport Pty Ltd has prepared this Land Use Plan in order to provide a clear plan- ning framework for use and development at Essendon Airport. The detail, terminology and definitions used in this Land Use Plan is wherever possible generally consistent with the Victoria Planning Provisions (VPPs) that existed at the time the Land Use Plan was prepared. The VPPs were subsequently amended by the Victorian Government via VC100 on 15 July 2013. Any changes to the Victorian Government’s planning provisions will be considered and in- corporated as part of a wider review of the Land Use Plan for the 2019 Master Plan. PURPOSE PAGE 1 OF 1 2013 ESSENDON AIRPORT LAND USE PLAN CONTENTS SECTION CLAUSE Purposes of this Land Use Plan CONTENTS Contents USER GUIDE User guide ESSENDON 20 Operation of the Essendon Airport Planning Policy AIRPORT Framework PLANNING POLICY 21 Essendon Airport Strategic Statement FRAMEWORK 22 Essendon Airport Planning Policies ZONES 31 Operation of zones Business Zones 34.02 Business 2 Zone 34.03 Business 3 Zone Special Purpose Zones 37.01 Special Use Zone OVERLAYS 41 Operation of Overlays PARTICULAR 51 Operation of particular provisions PROVISIONS 52.05 Advertising signs 52.06 Car parking 52.07 Loading and unloading of vehicles 52.10 Uses with adverse amenity potential 52.11 Home Occupation 52.12 Service station 52.13 Car wash 52.14 Motor vehicle, -

Report on Intrastate Air Services

VICTORIAN TRANSPORT STUDY REPORT ON INTRASTATE AIR SERVICES Ordered by the Legislative Assembly to be printed F. D. ATKINSON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER. MELBOURNE No. 46 VICTORIAN TRANSPORT STUDY The Honourable R.R.C. Maclellan, M.L.A., Minister of Transport, 570 Bourke Street, MELBOURNE, VIC. 3000, Dear Mr. Maclellan, I have the pleasure to submit herewith a report on Intrastate Air Services. This is one of a series of reports being prepared to make known the results of the Victorian Transport Study. Yours sincerely, W.M. Lonie. INTRASTATE AIR SERVICES CONTENTS: Summary 1. Introduction 2. Background 3. Submissions 4. Discussion 5. Recommendation 6. References SUMMARY Features of Victoria's aviation activities include a network of 36 major aerodromes, eight of which are owned by the Commonwealth Government, and a wide range of regular scheduled air services operated by international, national intrastate and commuter operators. Because of the importance of aviation to country people in communications with the State capital and other centres, and for connections to interstate and international air carriers, local government bodies throughout Victoria have accepted responsibility for the development and management of 27 licensed aerodromes. These aerodromes also form the basis of a number of other activities associated with aviation. Financial responsibility for them rests with Local Government, except that Commonwealth Government assistance is available for approved development and maintenance works under the Aerodrome Local Assistance Plan on a 50/50 basis with Local Government. Unfortunately, the atronage level of intrastate and commuter passenger and ight services, and the costs involved, have largely militated against the development of financially successful intrastate airline services, and against a level of charges by Local Government necessary to offset a proportion of the costs of maintaining and operating country aerodromes. -

T R a V E L L

sharpTHE TRAVELLER EDITION 1 FITNESS LIFESTYLE FOOD & WINE FILMS & FESTIVALS Managing Director’s Contents Welcome Inflight Health 4 The Tale of The Sharp Traveller 5 The Delightful Tastes of Adelaide 6 Work to Live, Not Live to Work 8 > Real Wealth Equals Quality Time > Return on Investment Sharp Contacts Helping to Build Sharper Communities: 9 Bookings > Sharp Airlines’ Community Support Program T: 1300 55 66 94 Welcome to Sharp Airlines’ new flight magazine, F: 03 5574 8258 Sharp Things to See and Do 10 The Sharp Traveller. E: [email protected] Seasonal Delights 11 Sharp Airlines is a leader in regional aviation, dedicated W: www.sharpairlines.com.au to delivering quality service across all aspects of the What’s On? 12 organisation, and The Sharp Traveller is no exception. Head Office Over the past few months we have worked hard to bring Fitness Tips to have you Flying in no Time 14 Hamilton Airport you this fresh and exciting publication, featuring a variety of The Sharp Files 16 articles from lifestyle and destination stories, to information Hensley Park Rd about your health and well-being. Hamilton VIC 3300 > Flying High – Jason Lipson The Sharp Traveller is designed to cater to readers by giving > What’s in My Wardrobe? - Annie Clifforth you an accurate and informed view about everything from Adelaide Office lifestyle and destinations, to your health and > Staff Profile – Sandi Jones Sir Richard William Ave well-being. Our goal is to provide you with the most up-to- Ones to Watch 18 date, stimulating news from across the nation, and from Adelaide Airport SA 5950 your own community. -

South-East Region Airport

Possible South-East Airport Pathway Plan Melbourne Implementation Plan Action 49: Plan for possible airport in South East Region Background Plan Melbourne 2017-2050 and Victoria’s eight regional growth plans all acknowledge the Action 48: Strategy for future gateways importance of maintaining and planning for adequate interstate and international gateway Protect options for future air and seaports terminal capacity to serve passengers and and intermodal terminals through freight to 2050 and beyond. appropriate planning frameworks…This should include decisions on the relative priorities for investment in: Bay West or the Port of Hastings Western Interstate Freight Terminal and/or the Beveridge Interstate Freight Terminal Avalon Airport and a potential South- East Airport. Action 49: Plan for possible airport in South East Region Finalise a preferred site beyond Koo Wee Rup, should demand warrant this beyond 2030. Preserve this future option by incorporating planning protection for flight Plan Melbourne Map 2: Melbourne 2050 Plan paths and noise contours and the Transport gateway – possible airport (indicative) alignment for a connection to the rail line at Clyde. Key actions in the Plan Melbourne Implementation Plan support future airport capacity planning. Previous proposals Plan Melbourne identifies the need to plan for a future possible airport in the south-east of Melbourne “to serve There have been several speculative proposals over the long-term needs of south-east Melbourne and the years for an airport to serve the long-term needs of Gippsland”. The airport would be developed the private south-east Melbourne and Gippsland. The general sector and serve one third of Victoria’s population location in the south east has been identified as early (including over 300,000 residents of the broader as 2002 in Melbourne 2030. -

A New Employment Precinct for Melbourne's North

A New Employment Precinct for Melbourne’s North CREATING INVESTMENT AND JOBS IN AIRPORT WEST AND ESSENDON FIELDS The Metropolitan Planning Authority, aviation and employment focus at a site existing industry, guides infrastructure Moonee Valley City Council and Essendon with excellent access to Melbourne’s CBD improvements, improves amenity and Fields are working in partnership to and Victoria’s major regional centres. preserves the area’s heritage values. prepare a framework plan to guide the Already home to 639 businesses and The precinct has easy access to major development of an exciting new aviation a workforce of more than 9000, this road and freight links, as well as and employment precinct in Melbourne’s precinct is identified in Plan Melbourne public transport. Airport West and inner north. as a key transport gateway and site of Essendon Fields have direct access to the Planning for the Airport West and state significance. Tullamarine Freeway, as well as proximity Essendon Fields Employment Precinct to the Calder Freeway, Hume Freeway, This key urban renewal and business will incorporate Essendon Airport’s Western Ring Road and Bell Street. location in Melbourne’s inner north will masterplan and Moonee Valley’s Airport take in Essendon Fields and a section of Development of the precinct responds to West structure plan into an overall Airport West. It will cover approximately the 20-minute neighbourhood initiative framework plan to create an exciting 688 hectares in Melbourne’s aviation outlined in Plan Melbourne, where locals business precinct with the capacity to corridor, 12 kilometres northwest of can live and enjoy working locally.