Life in the New Kingdom Town of Sai Island: Some New Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No. 6 a NEWSLETTER of AFRICAN ARCHAEOLOGY May 19 75 Edited

- No. 6 A NEWSLETTER OF AFRICAN ARCHAEOLOGY May 1975 Edited by P.L. Shinnie and issued from the Department of Archaeology, The University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta T2N lN4, Canada. (This issue edited by John H. Robertson.) I must apologize for the confusion which has developed con- cerning this issue. A notice was sent in February calling for material to be sent by March 15th. Unfortunately a mail strike in Canada held up the notices, and some people did not receive them until after the middle of March. To make matters worse I did not get back from the Sudan until May 1st so the deadline really should have been for the end of April. My thanks go to the contributors of this issue who I am sure wrote their articles under pressure of trying to meet the March 15th deadline. Another fumble on our part occurred with the responses we received confirming an interest in future issues of Nyame Akuma Professor ~hinnie'sintent in sending out the notice was to cull the now over 200 mailing list down to those who took the time to respond to the notice. Unfortunately the secretaries taking care of the-mail in Shinnie's absence thought the notice was only to check addresses, and only changes in address were noted. In other words, we have no record of who returned the forms. I suspect when Professor Shinnie returns in August he will want to have another go at culling the mailing list . I hope this issue of Nyame Akuma, late though it is, reaches everyone before they go into the field, and that everyone has an enjoyable and productive summer. -

In Lower Nubia During the UNESCO Salvage Campaign in the 1960S, Only One, Fadrus, Received Any Robust Analytical Treatment

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CONTINUITY AND CHANGE: A REEVALUATION OF CULTURAL IDENTITY AND “EGYPTIANIZATION” IN LOWER NUBIA DURING THE NEW KINGDOM A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY LINDSEY RAE-MARIE WEGLARZ CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JUNE 2017 Copyright © 2017 Lindsey Rae-Marie Weglarz All rights reserved Table of Contents List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................... vi List of Tables .............................................................................................................................................. viii Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... ix Abstract ......................................................................................................................................................... x Chapter 1 : Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 Historical Background ................................................................................................................................ 3 Lower Nubia before the New Kingdom ................................................................................................. 3 The Conquest -

The Egyptian Fortress on Uronarti in the Late Middle Kingdom

and omitting any later additions. As such, it would be fair to Evolving Communities: The argue that our notion of the spatial organization of these sites and the lived environment is more or less petrified at Egyptian fortress on Uronarti their moment of foundation. in the Late Middle Kingdom To start to rectify these shortcomings, we have begun a series of small, targeted excavations within the fortress; we Christian Knoblauch and Laurel Bestock are combining this new data with a reanalysis of unpub- lished field notes from the Harvard/BMFA excavations as Uronarti is an island in the Batn el-Hagar approximately 5km well as incorporating important new studies on the finds from the Egyptian Middle Kingdom border with Kush at the from that excavation, for example that on the sealings by Semna Gorge. The main cultural significance of the island Penacho (2015). The current paper demonstrates how this stems from the decision to erect a large trapezoidal mnnw modest approach can yield valuable results and contribute fortress on the highest hill of the island during the reign of to a model for the development of Uronarti and the Semna Senwosret III. Together with the contemporary fortresses at Region during the Late Middle Kingdom and early Second Semna West, Kumma, Semna South and Shalfak, Uronarti Intermediate Period. constituted just one component of an extensive fortified zone at the southern-most point of direct Egyptian control. Block III Like most of these sites (excepting Semna South), Uronarti The area selected for reinvestigation in 2015-2016 was a was excavated early in the history of Sudanese archaeology small 150m2 part of Block III (Figure 1, Plate 1) directly by the Harvard/Boston Museum of Fine Arts mission in the to the local south of the treasury/granary complex (Blocks late 1920’s (Dunham 1967; Reisner 1929; 1955; 1960; Wheeler IV-VI) (Dunham 1967, 7-8; Kemp 1986) and to the north 1931), and was long believed to have been submerged by of the building probably to be identified as the residence of Lake Nubia (Welsby 2004). -

The Lower Nubian Egyptian Fortresses in the Middle Kingdom: a Strategic Point of View

Athens Journal of History - Volume 5, Issue 1 – Pages 31-52 The Lower Nubian Egyptian Fortresses in the Middle Kingdom: A Strategic Point of View By Eduardo Ferreira The Ancient Egypt was a highly militarized society that operated within various theaters of war. From the Middle Kingdom period to the following times, warfare was always present in the foreign and internal policy of the pharaohs and their officers. One of these was to build a network of defensive structures along the river Nile, in the regions of the Second Cataract and in Batn el-Hagar, in Lower Nubia. The forts were relevant in both the defense and offensive affairs of the Egyptian army. Built in Lower Nubia by the pharaohs of the XII dynasty of the Middle Kingdom, these fortresses providing support to the armies that usually came from the North in campaign and allowed the ancient Egyptians to control the frontier with Kush. In fact, one of the most important features of these fortresses was the possibility to control specific territorial points of larger region which, due to it’s characteristics, was difficult to contain. Although they were built in a period of about thirty-two years, these strongholds throughout the reign of Senuseret I until the rulership of Senuseret III, they demonstrate a considerable diversification in terms of size, defenses, functions, and the context operated. They were the main reason why Egypt could maintain a territory so vast as the Lower Nubia. In fact, this circumstance is verified in the Second Intermediate Period when all the forts were occupied by Kerma, a chiefdom that araised in Upper Nubia during the end of the Middle Kingdom, especially after c. -

Diplomová Práce

Univerzita Karlova Filozofická fakulta Český egyptologický ústav Diplomová práce PhDr. Bc. Jan Rovenský, Ph.D. The Land to its Limits: Borders and Border Stelae in Ancient Egypt Praha 2021 Vedoucí práce: doc. PhDr. Jana Mynářová, Ph.D. 1 Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Jana Mynářová for her stalwart support (not only) during the writing of this thesis. Many thanks are due to the other members of the Czech Institute of Egyptology for their help and guidance. This thesis would never have seen the light of day without the support of my family – from those who have departed, as well as those who have arrived. Thank you for your everlasting patience. 2 Prohlášení: Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracoval samostatně, že jsem řádně citoval všechny použité prameny a literaturu a že práce nebyla využita v rámci jiného vysokoškolského studia či k získání jiného nebo stejného titulu. V Praze 9. dubna 2021 Jan Rovenský 3 Klíčová slova: hraniční stéla; hranice; Senusret III; Thutmose I; Thutmose III; Núbie Keywords: border stela; boundary; frontier; Senusret III, Thutmose I; Thutmose III; Nubia 4 Abstrakt Diplomová práce zkoumá tzv. hraniční stély a věnuje se i konceptu hranic ve starověkém Egyptě. Na základě historické, archeologické a epigrafické analýzy daných artefaktů dochází k závěru, že by se v egyptologii měla přestat používat kategorie „hraniční stéla“, jelikož existuje jen jediný monument, který lze označit jako hraniční stélu, jmenovitě stélu z 8. roku vlády Senusreta III. objevené v pevnosti v Semně. Abstract This M.A. thesis examines so-called border stelae in ancient Egypt, as well as the concept of the border. -

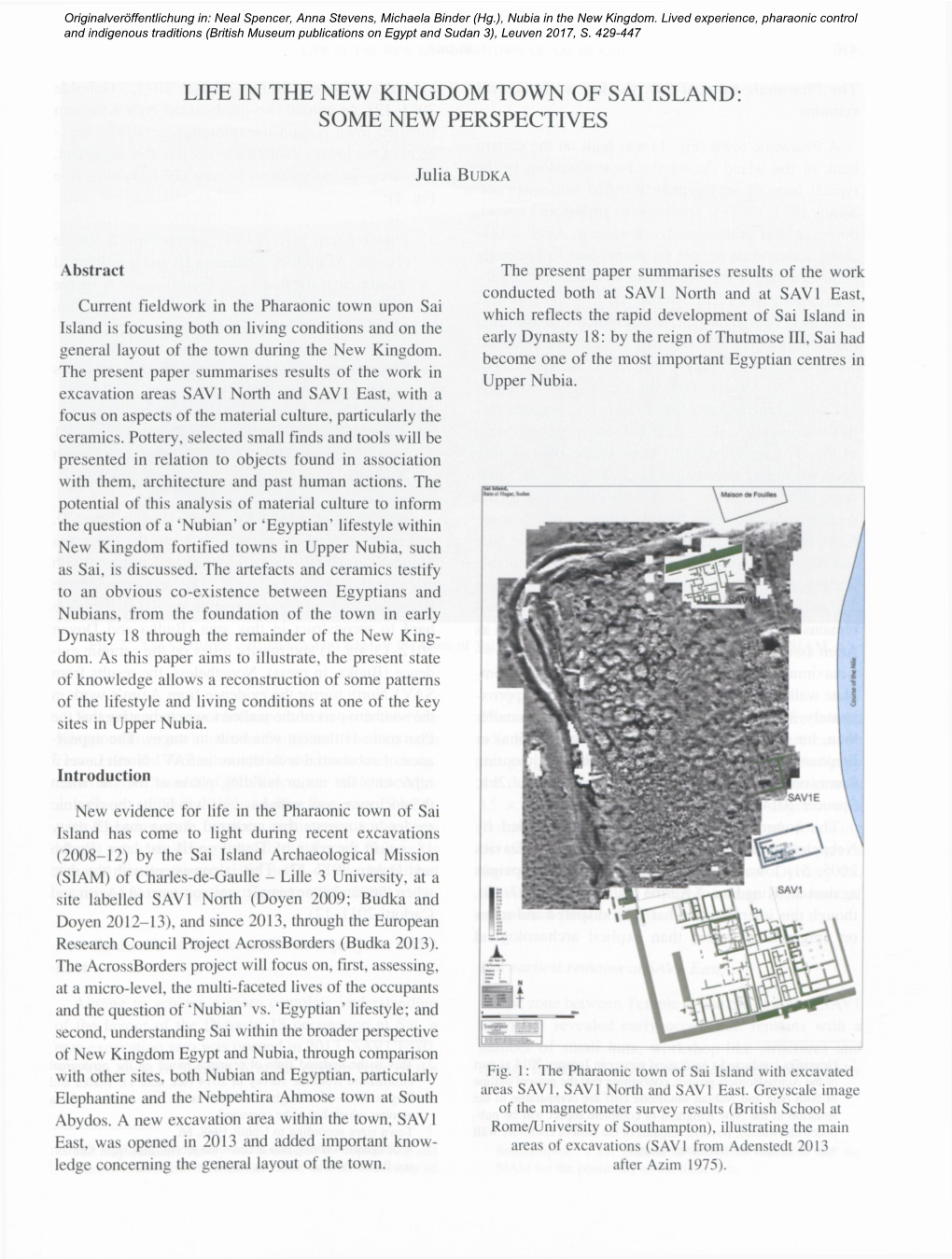

The 18Th Dynasty on Sai Island

SUDAN & NUBIA th in the last few years (Figure 1). A stratigraphic single context The 18 Dynasty on Sai Island excavation was conducted at all sites, using structure from motion applications to document the individual surfaces – new data from excavations (for this method and documentation technique see Fera and in the town area and Budka 2016). SAV1 Northeast cemetery SAC5 Previously, the eastern town wall could not be traced and it was assumed that it collapsed into the Nile at some uncertain Julia Budka point in antiquity (Geus 2004, 115, fig. 89, based on Azim 1975, 94, pl. II). Recent fieldwork and geological surveys of Introduction the sandstone cliff allowed a modification of this assessment Sai is one of the most important New Kingdom sites in (Budka 2015a, 60; 2015b, 41), evaluating severe erosion in Upper Nubia – its significant role derives from a strong this part of the island as highly unlikely. In line with this, Kerma presence on the island prior to the New Kingdom the steep cliff at the north-eastern corner of the town, site (see Gratien 1986; Vercoutter 1986) and the fact that both the 8-B-522, clearly functioned as a mooring area in Christian th town and cemetery of the 18 Dynasty can be investigated times, as is well attested by Medieval graffiti and mooring (Budka 2015b; 2016). The New Kingdom town is situated at rings carved out of the rock for tying ships’ ropes at a very the eastern edge of the island; the largest associated Egyptian high level of the cliff (Hafsaas-Tsakos and Tsakos 2012, 85- cemetery, SAC5, less than 1km further to the south. -

The Middle Kingdom in Nubia by George Wood

From Raids to Conquest (and Retreat): The Middle Kingdom in Nubia by George Wood "Nubians, I was hoping to avoid them"1 It seems that, for the typical ancient Egyptian, the world was the Two Lands, the strip of black earth along the Nile River innundation from the Delta in the north to Elephantine island at the First Cataract in the south. Moving away from the country was unusual, and with a mindset focused on a pleasant afterlife, the risk of being buried outside the Two Lands without the proper preparation should have been unthinkable. "The Story of Sinuhe" not only reflects the homesickness of an Egyptian in exile, it would also seem to underline the vital importance of being put to earth within the Two Lands if one is to enjoy eternal life. Outside the Two Lands the earth was red and dry, or the rivers ran in the sky2 or backwards (north to south like the Euphrates). So longterm adventures abroad would have been somewhat contrary to the core Egyptian spirit. (There is another opinion here, Williams3 says that during the 12th Dynasty, the period just after Sinuhe, there were many expatriates who left Egypt.) The New Kingdom empire in Syria-Palestine was a bit like the Soviet domination of Eastern Europe after 1945, a buffer zone prompted by invasions from outside (Sweden in the 18th century, France in the 19th, and Germany twice in the 20th). In the case of ancient Egypt, the move into the Levant during the New Kingdom was in response to the trauma of the Hykos invasion. -

Forgotten Fortress Returning to Uronarti

Forgotten Fortress Returning to Uronarti Laurel Bestock Uronarti fortress seen from the north. Kite aerial photograph by Kathryn Howley and Laurel Bestock. ronarti, located in northern Sudan, is the site of one the physical relationships between modern nation-states is at all of a series of fortresses built by the Egyptian kings times problematic when applied to ancient Egypt, and in cer- of the Twelfth Dynasty to control the gold-bearing tain periods the territorial control of Egypt certainly extended well beyond its notional boundaries. The Middle Kingdom (ca. Uterritory of Lower Nubia. Long thought to be inaccessible to 2055–1650 b.c.e.) was the first great period of expansion; dur- further archaeological research due to the flooding behind the ing this period the kings of Egypt’s Twelfth Dynasty established Aswan High Dam, two of the forts have recently been found to control over Lower Nubia (now in southern Egypt and northern be remaining above water. The rediscovery of these forgotten Sudan) and maintained that control with a series of monumen- fortresses and the beginning of a new project at Uronarti allow tal fortifications (fig. 1). Most of these were built along the Nile us to pose questions about not only the state-imposed stamp of itself, although we increasingly recognize that control over the desert was an integrated part of this system. colonialism in this place but also the more complex long-term The fortress-based domination of Lower Nubia in the Middle engagements and lifestyles that grew up around it. The Uronarti Kingdom had interwoven military, economic, and ideologi- Regional Archaeological Project is investigating some aspects cal components, and was a major undertaking of the complex of lived experience in this outpost.1 bureaucratic state of the time. -

William Y Adams Social Class and Local Tradition in Nubia: the Evidence from Archaeology

William Y Adams Social class and local tradition in Nubia: The evidence from archaeology Adams, W.Y. 1965a Architectural evolution of the Nubian church, 500-1400 A.D., JARCE 4, 87-139 https://doi.org/10.2307/40001005 Adams, W.Y. 1965b Sudan Antiquities Service excavations at Meinarti, 1963-64, Kush 13, 148-176 Adams, W.Y. 1977 Nubia, Corridor to Africa, London-Princeton Adams, W.Y. 1985 Doubts about the 'Lost Pharaohs', JNES 44, 185-192 https://doi.org/10.1086/373128 Adams, W.Y. 1986 Islamic archaeology in Nubia: an introductory survey [in:] Acts Uppsala 1986, 327- 361 Adams, W.Y. 1994a Castle-houses of Late Medieval Nubia, ANM 6, 11-46 Adams, W.Y. 1994b Kulubnarti, vol. I: The Architectural Remains, Lexington, KY Adams, W.Y. 1996 Qasr Ibrim: The Late Medieval Period [=Egypt Exploration Society, Excavation Memoir 59], London Adams, W.Y. 1998 Toward a comparative study of Christian Nubian burial practice, ANM 8, 13-42 Adams, W.Y. 2000 Meinarti, vol. I: The Late Meroitic, Ballaña, and Transitional Occupation [=Sudan Archaeological Research Society Publications, No. 5], London Adams, W.Y. 2001a The Ballaña kingdom and culture [in:] E.M. Yamauchi (ed.), Africa and Africans in Antiquity, East Lansing, MI, 151-179 Adams, W.Y. 2001b Meinarti, vol. II: The Early and Classic Christian Phases [=Sudan Archaeological Research Society Publications, No. 6], London Adams, W.Y. 2003 Meinarti, vols. IV and V: The Church and the Cemetery, and the History of Meinarti [=Sudan Archaeological Research Society Publications, No. 11], London Adams, W.Y. 2004 The West Bank Survey from Faras to Gemai, vol. -

Reconstructing the Pre-Meroitic Indigenous Pantheon of Kush

Journal of Journal of Ancient near Ancient Near Eastern Eastern Religions 18 (2018) 167–189 Religions brill.com/jane Reconstructing the Pre-Meroitic Indigenous Pantheon of Kush M. Victoria Almansa-Villatoro Brown University [email protected] Abstract This article sets out to address questions concerning local religious traditions in an- cient Nubia. Data concerning Egyptian gods in the Sudan are introduced, then the existence of unattested local pre-Meroitic gods is reconstructed using mainly exter- nal literary sources and an analysis of divine names. A review of other archaeological evidence from an iconographic point of view is also attempted, concluding with the presentation of Meroitic gods and their relation with earlier traditions. This study pro- poses that Egyptian religious beliefs were well integrated in both official and popular cults in Nubia. The Egyptian and the Sudanese cultures were constantly in contact in the border area and this nexus eased the transmission of traditions and iconographi- cal elements in a bidirectional way. The Meroitic gods are directly reminiscent of the reconstructed indigenous Kushite pantheon in many aspects, and this fact attests to an attempt by the Meroitic rulers to recover their Nubian cultural identity. Keywords Nubia – Egypt – local religion – Meroitic Gods – Dedwen – Miket – Apedemak – Rahes 1 Introduction During the 25th Dynasty, the Kushite world was significantly influenced by Egyptian gods who entered the Nubian pantheon and were worshipped throughout various different -

LAS FORTALEZAS Los Testimonios Que Han Llegado Hasta Nosotros

La guen'a en Oriente Próximo y Egipto POLÍTICA DEFENSIVA EN NUBlA: LAS FORTALEZAS Esther Pons Mellado Museo Arqueológico Nacional Los testimonios que han llegado hasta nosotros sobre los antiguos egipcios nos muestran que éstos se adentraron en Nubia (fig, 1), o lo que es lo mismo en nb, País del Oro, desde las primeras dinastías, cuya frontera natural entre ambos países parece que se encontraba en Dyebel el Silsila, aunque, fue desplazada hasta la Primera Catarata, lugar donde el faraón Aba levantó la Fortaleza de Elefantina L. Geográficamente fue dividida de f0l1lla rutificial en dos grandes áreas, que estaban bajo la dirección de un Virrey: a) Baja Nubia o Vauat. Comprende el territorio que va de la Primera (hoy la frontera actual entre Egipto y Sudán) hasta la Segunda Catarata. Dada su espléndida situación geográfica constituyó desde época muy temprana un corredor de transporte, tanto hacia Oriente como hacia Occidente, dando además acceso a un gran número de minas, principalmente de oro, y canteras, situadas a lo largo de todo el desierto nubio. b) Alta Nubia o Cush. Comprende el territorio que va de la Segunda a la Cuarta Catru'ata, y su interés e importancia para los egipcios tendrá lugar a prutir de las primeras dinastías del Imperio Medio. Desde los comienzos, la política egipcia en el desierto de Nubia estuvo claramente mru'cada por la construcción de unas determinadas edificaciones, las Fortalezas, que no sólo iban a servir para guardar el material que extraían de las minas, sino y, sobre todo, para albergar al contingente militar enviado a dicho desierto y como lugar de defensa contra posibles ataques enemigos, que en gran palte estuvieron fuertemente relacionados por el control de las minas. -

Egyptian Body Size: a Regional and Worldwide Comparison

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2011 Egyptian Body Size: A Regional and Worldwide Comparison Michelle H. Raxter University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, Anatomy Commons, and the Evolution Commons Scholar Commons Citation Raxter, Michelle H., "Egyptian Body Size: A Regional and Worldwide Comparison" (2011). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3305 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Egyptian Body Size: A Regional and Worldwide Comparison by Michelle Helene Raxter A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Lorena Madrigal, Ph.D. David A. Himmelgreen, Ph.D. Christopher B. Ruff, Ph.D. E. Christian Wells, Ph.D. Sonia R. Zakrzewski, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 10, 2011 Keywords: postcrania, ancient health, ecogeographic patterning, Northeast Africa, Egypt, Nubia Copyright © 2011, Michelle Helene Raxter ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my all-star dissertation committee: Dr. Christian Wells. Dr. Wells was so great at explaining details to me, especially in stats. He is also super super cool. Dr. David Himmelgreen. Points Dr. Himmelgreen has highlighted to me have really helped me improve my work.