Fort Rock Cave: Assessing the Site’S Potential to Contribute to Ongoing Debates About How and When Humans Colonized the Great Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radiocarbon Evidence Relating to Northern Great Basin Basketry Chronology

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title Radiocarbon Evidence Relating to Northern Great Basin Basketry Chronology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/52v4n8cf Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 20(1) ISSN 0191-3557 Authors Connolly, Thomas J Fowler, Catherine S Cannon, William J Publication Date 1998-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California REPORTS Radiocarbon Evidence Relating ity over a span of nearly 10,000 years (cf. to Northern Great Basin Cressman 1942, 1986; Connolly 1994). Stages Basketry Chronology 1 and 2 are divided at 7,000 years ago, the approximate time of the Mt. Mazama eruption THOMAS J. CONNOLLY which deposited a significant tephra chronologi Oregon State Museum of Anthropology., Univ. of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403. cal marker throughout the region. Stage 3 be CATHERINE S. FOWLER gins after 1,000 years ago,' when traits asso Dept. of Anthropology, Univ. of Nevada, Reno, NV ciated with Northern Paiute basketmaking tradi 89557. tions appear (Adovasio 1986a; Fowler and Daw WILLIAM J. CANNON son 1986; Adovasio and Pedler 1995; Fowler Bureau of Land Management, Lakeview, OR 97630. 1995). During Stage 1, from 11,000 to 7,000 years Adovasio et al. (1986) described Early ago, Adovasio (1986a: 196) asserted that north Holocene basketry from the northern Great ern Great Basin basketry was limited to open Basin as "simple twined and undecorated. " Cressman (1986) reported the presence of and close simple twining with z-twist (slanting decorated basketry during the Early Holo down to the right) wefts. Fort Rock and Spiral cene, which he characterized as a "climax Weft sandals were made (see Cressman [1942] of cultural development'' in the Fort Rock for technical details of sandal types). -

0205683290.Pdf

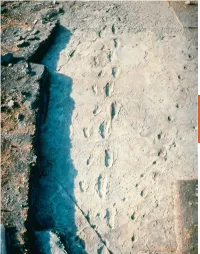

Hominin footprints preserved at Laetoli, Tanzania, are about 3.6 million years old. These individuals were between 3 and 4 feet tall when standing upright. For a close-up view of one of the footprints and further information, go to the human origins section of the website of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/ humanorigins/ha/laetoli.htm. THE EVOLUTION OF HUMANITY AND CULTURE 2 the BIG questions v What do living nonhuman primates tell us about OUTLINE human culture? Nonhuman Primates and the Roots of Human Culture v Hominin Evolution to Modern What role did culture play Humans during hominin evolution? Critical Thinking: What Is Really in the Toolbox? v How has modern human Eye on the Environment: Clothing as a Thermal culture changed in the past Adaptation to Cold and Wind 12,000 years? The Neolithic Revolution and the Emergence of Cities and States Lessons Applied: Archaeology Findings Increase Food Production in Bolivia 33 Substantial scientific evidence indicates that modern hu- closest to humans and describes how they provide insights into mans have evolved from a shared lineage with primate ances- what the lives of the earliest human ancestors might have been tors between 4 and 8 million years ago. The mid-nineteenth like. It then turns to a description of the main stages in evolu- century was a turning point in European thinking about tion to modern humans. The last section covers the develop- human origins as scientific thinking challenged the biblical ment of settled life, agriculture, and cities and states. -

The Chewaucan Cave Cache: the Upper and Lower Chewaucan Marshes

Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology | Vol. 33, No. 1 (2013) | pp. 72–87 The Chewaucan Cave Cache: the Upper and Lower Chewaucan marshes. Warner provided a typed description of the cave location and A Specialized Tool Kit from the collector’s findings; that document is included in the Eastern Oregon museum accession file. He described the cave as being nearly filled to the ceiling with silt, stone, sticks, animal ELIZABETH A. KALLENBACH Museum of Natural and Cultural History bone, and feces. On their first day of excavation, the 1224 University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403-1224 diggers sifted through fill and basalt rocks from roof fall, finding projectile points, charred animal bone, and The Chewaucan Cave cache, discovered in 1967 by relic pieces of cordage and matting. On the second day, they collectors digging in eastern Oregon, consists of a large discovered the large grass bag. grass bag that contained a number of other textiles and Warner’s description noted that the bag was leather, including two Catlow twined baskets, two large “located about eight feet in from the mouth of the cave folded linear nets, snares, a leather bag, a badger head and two feet below the surface.” It was covered by a pouch, other hide and cordage, as well as a decorated piece of tule matting, and lay on a bed of grass, with a basalt maul. One of the nets returned an Accelerator Mass sage rope looped around the bag. The bag contained Spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon date of 340 ± 40 B.P. two large Catlow twined baskets, a leather bag, and The cache has been noted in previous publications, but leather-wrapped cordage and sinew bundles. -

In Search of the First Americas

In Search of the First Americas Michael R. Waters Departments of Anthropology and Geography Center for the Study of the First Americans Texas A&M University Who were the first Americans? When did they arrive in the New World? Where did they come from? How did they travel to the Americas & settle the continent? A Brief History of Paleoamerican Archaeology Prior to 1927 People arrived late to the Americas ca. 6000 B.P. 1927 Folsom Site Discovery, New Mexico Geological Estimate in 1927 10,000 to 20,000 B.P. Today--12,000 cal yr B.P. Folsom Point Blackwater Draw (Clovis), New Mexico 1934 Clovis Discovery Folsom (Bison) Clovis (Mammoth) Ernst Antevs Geological estimate 13,000 to 14,000 B.P. Today 13,000 cal yr B.P. 1935-1990 Search continued for sites older than Clovis. Most sites did not stand up to scientific scrutiny. Calico Hills More Clovis sites were found across North America The Clovis First Model became entrenched. Pedra Furada Tule Springs Clovis First Model Clovis were the first people to enter the Americas -Originated from Northeast Asia -Entered the Americas by crossing the Bering Land Bridge and passing through the Ice Free Corridor around 13,600 cal yr B.P. (11,500 14C yr B.P.) -Clovis technology originated south of the Ice Sheets -Distinctive tools that are widespread -Within 800 years reached the southern tip of South America -Big game hunters that killed off the Megafauna Does this model still work? What is Clovis? • Culture • Era • Complex Clovis is an assemblage of distinctive tools that were made in a very prescribed way. -

New Research at Paisley Caves: Applying New Integrated Analytical Approaches to Understanding Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Site Formation Processes

Shillito L-M, Blong J, Jenkins D, Stafford TW, Whelton H, McDonough K, Bull I. New Research at Paisley Caves: Applying New Integrated Analytical Approaches to Understanding Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Site Formation Processes. PaleoAmerica 2018 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2017.1396167 Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited DOI link to article: https://doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2017.1396167 Date deposited: 23/10/2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk PaleoAmerica A journal of early human migration and dispersal ISSN: 2055-5563 (Print) 2055-5571 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ypal20 New Research at Paisley Caves: Applying New Integrated Analytical Approaches to Understanding Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Site Formation Processes Lisa-Marie Shillito, John C. Blong, Dennis L. Jenkins, Thomas W. Stafford Jr, Helen Whelton, Katelyn McDonough & Ian D. Bull To cite this article: Lisa-Marie Shillito, John C. Blong, Dennis L. Jenkins, Thomas W. Stafford Jr, Helen Whelton, Katelyn McDonough & Ian D. Bull (2018): New Research at Paisley Caves: Applying New Integrated Analytical Approaches to Understanding Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Site Formation Processes, PaleoAmerica, DOI: 10.1080/20555563.2017.1396167 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2017.1396167 © 2018 The Author(s). -

Quaternary Studies Near Summer Lake, Oregon Friends of the Pleistocene Ninth Annual Pacific Northwest Cell Field Trip September 28-30, 2001

Quaternary Studies near Summer Lake, Oregon Friends of the Pleistocene Ninth Annual Pacific Northwest Cell Field Trip September 28-30, 2001 springs, bars, bays, shorelines, fault, dunes, etc. volcanic ashes and lake-level proxies in lake sediments N Ana River Fault N Paisley Caves Pluvial Lake Chewaucan Slide Mountain pluvial shorelines Quaternary Studies near Summer Lake, Oregon Friends of the Pleistocene Ninth Annual Pacific Northwest Cell Field Trip September 28-30, 2001 Rob Negrini, Silvio Pezzopane and Tom Badger, Editors Trip Leaders Rob Negrini, California State University, Bakersfield, CA Silvio Pezzopane, United States Geological Survey, Denver, CO Rob Langridge, Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences, Lower Hutt, New Zealand Ray Weldon, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR Marty St. Louis, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Summer Lake, Oregon Daniel Erbes, Bureau of Land Management, Carson City, Nevada Glenn Berger, Desert Research Institute, University of Nevada, Reno, NV Manuel Palacios-Fest, Terra Nostra Earth Sciences Research, Tucson, Arizona Peter Wigand, California State University, Bakersfield, CA Nick Foit, Washington State University, Pullman, WA Steve Kuehn, Washington State University, Pullman, WA Andrei Sarna-Wojcicki, United States Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA Cynthia Gardner, USGS, Cascades Volcano Observatory, Vancouver, WA Rick Conrey, Washington State University, Pullman, WA Duane Champion, United States Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA Michael Qulliam, California State University, Bakersfield, -

The Terminal Pleistocene/Early Holocene Record in the Northwestern Great Basin: What We Know, What We Don't Know, and How We M

PALEOAMERICA, 2017 Center for the Study of the First Americans http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2016.1272395 Texas A&M University REVIEW ARTICLE The Terminal Pleistocene/Early Holocene Record in the Northwestern Great Basin: What We Know, What We Don’t Know, and How We May Be Wrong Geoffrey M. Smitha and Pat Barkerb aGreat Basin Paleoindian Research Unit, Department of Anthropology, University of Nevada, Reno, NV, USA; bNevada State Museum, Carson City, NV, USA ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The Great Basin has traditionally not featured prominently in discussions of how and when the New Great Basin; Paleoindian World was colonized; however, in recent years work at Oregon’s Paisley Five Mile Point Caves and archaeology; peopling of the other sites has highlighted the region’s importance to ongoing debates about the peopling of the Americas Americas. In this paper, we outline our current understanding of Paleoindian lifeways in the northwestern Great Basin, focusing primarily on developments in the past 20 years. We highlight several potential biases that have shaped traditional interpretations of Paleoindian lifeways and suggest that the foundations of ethnographically-documented behavior were present in the earliest period of human history in the region. 1. Introduction comprehensive review of Paleoindian archaeology was published two decades ago. We also highlight several The Great Basin has traditionally not been a focus of biases that have shaped traditional interpretations of Paleoindian research due to its paucity of stratified and early lifeways in the region. well-dated open-air sites, proboscidean kill sites, and demonstrable Clovis-aged occupations. Until recently, the region’s terminal Pleistocene/early Holocene (TP/ 2. -

Identifying Cultural Migration in Western North America Through

University of Nevada, Reno Identifyin ultural Migration n estern orth meric through orphometric nalysi Early olocene rojectile Points A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology By Amanda J. Hartman Dr. Geoffrey M. Smith/Thesis Advisor May 2019 © by Amanda J. Hartman 2019 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by Entitled be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of , Advisor , Committee Member , Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School i Abstract Migrations and interactions between early populations are a major focus of Paleoindian research. Because there is a paucity of genetic data, researchers use distinctive projectile point styles to infer temporal and spatial diffusion of ideas between in situ populations or population migrations. However, archaeologists often study culture areas defined by physiographic features, which may preclude observation of stylistic continuity. Stemmed points occur at least as early as 13,500 cal BP (Davis et al. 2014) in the Intermountain West and continue throughout the Paleoindian Period (14,500- 8000 cal BP). Stemmed forms occur during both the Middle and Late Paleoindian periods (11,500-8000 cal BP) in the northern Great Plains. Prior research has identified a likeness between Late Paleoindian points from these two regions: Windust in the Intermountain West and Cody on the Great Plains. In this thesis, I test the hypothesis that Windust and Cody projectile points bear enough morphological similarity to imply transmontane movement of people and/or ideas during the Early Holocene. -

Nuevas Evidencias De Restos De Mamíferos Marinos En El Magdaleniense: Los Datos De La Cueva De Las Caldas (Asturias, España)

arqueo59art03.qxd:munibepajaros2008.qxd 23/12/08 18:40 Página 47 MUNIBE (Antropologia-Arkeologia) nº 59 47-66 SAN SEBASTIÁN 2008 ISSN 1132-2217 Recibido: 2008-09-01 Aceptado: 2008-11-05 Nuevas evidencias de restos de mamíferos marinos en el Magdaleniense: los datos de La Cueva de Las Caldas (Asturias, España) New Evidence of Marine Mammal Remains during the Magdalenian: Data from Las Caldas Cave (Asturias, Spain) PALABRAS CLAVES: Mamíferos marinos, objetos de adorno-colgantes, Magdaleniense, Región Cantábrica KEY WORDS: Marine mammals, Pendants, Magdalenian, Cantabrian Spain. GAKO-HITZAK: itsas ugaztunak, apaingarriak-zintzilikarioak, Madeleine aldia, Kantabriar eskualdea María Soledad CORCHÓN-RODRÍGUEZ(1), Esteban ÁLVAREZ-FERNÁNDEZ(2) RESUMEN En este artículo se estudian, desde el punto de vista tecnológico, los objetos de adorno-colgantes realizados en dientes de mamíferos marinos (foca, cachalote, calderón) procedentes de los niveles del Magdaleniense medio de la Cueva de Las Caldas. También se hace una revisión de otras evidencias arqueológicas de estos animales en contextos arqueológicos y se discuten las relaciones costa-interior de los grupos de cazadores recolectores en el territorio europeo en el Paleolítico. ABSTRACT This paper studies, from the technological point of view, a number of pendants made from the teeth of marine mammals (seal, sperm whale and pilot whale) recovered in middle Magdalenian levels at Cueva de Las Caldas. It also reviews other evidence of these animals that has been found in archaeological contexts and discusses the coastal-inland relationships of hunter-gatherer groups in Europe in the Palaeolithic. LABURPENA Artikulu honetan, itsas ugaztunen (itsas txakurren, kaxaloteen, kalderoien) hortzekin egindako apaingarri-zintzilikarioak aztertuko ditugu ikuspegi tek- nologikotik. -

TABLE 6.3 Significant Archaeological Sites in North America Older Than 5,000 Years

TABLE 6.3 Significant Archaeological Sites in North America Older than 5,000 Years Site Name Description Bluefish Located in present-day Yukon Territory, Bluefish Caves is significant because it provides Caves evidence of people in Beringia during the last ice age. The site contains artifacts made of stone and bone as well as butchered animal remains. Most archaeologists accept dates between 15,000 and 12,000 years ago, although some suggest dates in the range of 25,000 years ago. Cactus Hill This site is located in Virginia. It is widely accepted as being older than 12,000 years, but the precise antiquity is uncertain. Some suggest that the site may be as old as 19,000 to 17,000 years, but these dates are contested. Gault This site, located in Texas, was a Clovis camp and was likely first occupied more than 12,000 years ago. The assemblage includes more than one million artifacts, includ- ing several hundred thousand that are more than 9,000 years old. The site is particularly significant for showing the diversity of diet, which, contrary to popular belief, indicates that mammoths and other large game were only a small part of the Clovis diet. The site is also significant in providing what may be the oldest art in North America, in the form of more than 100 incised stones. Meadowcroft Meadowcroft Rockshelter, located in Pennsylvania, is widely considered to contain depos- its that are at least 12,000 years old. Some suggest the deposits may be as old as 19,000 years, but these dates are contested. -

Cordage, Basketry and Containers at the Pleistocene–Holocene Boundary in Southwest Europe

Vegetation History and Archaeobotany https://doi.org/10.1007/s00334-019-00758-x REVIEW Cordage, basketry and containers at the Pleistocene–Holocene boundary in southwest Europe. Evidence from Coves de Santa Maira (Valencian region, Spain) J. Emili Aura Tortosa1 · Guillem Pérez‑Jordà1,2 · Yolanda Carrión Marco1 · Joan R. Seguí Seguí3 · Jesús F. Jordá Pardo4 · Carles Miret i Estruch5 · C. Carlos Verdasco Cebrián6 Received: 13 March 2019 / Accepted: 31 October 2019 © The Author(s) 2019 Abstract In this study we present evidence of braided plant fbres and basketry imprints on clay recovered from Coves de Santa Maira, a Palaeolithic-Mesolithic cave site located in the Mediterranean region of Spain. The anatomical features of these organic fbre remains were identifed in the archaeological material and compared with modern Stipa tenacissima (esparto grass). Based on direct dating, the fragments of esparto cord from our site are the oldest worked plant fbres in Europe. Sixty frag- ments of fred clay are described. The clay impressions have allowed us to discuss the making of baskets and containers. According to their attributes and their functional interpretation, we have grouped them into fve types within two broad categories, hearth plates and baskets or containers. The clay pieces identifed as fragments of containers with basketry impressions are less common than those of hearth plate remains and they are concentrated in the Epipalaeolithic occupation material (13.2–10.2 ka cal BP). The clay impressions from Santa Maira indicate that some fbres were treated or fattened, a preparation process that is known from historical and ethnological sources. Keywords Perishable technologies · Plant fbres · Imprints on clay · Epipalaeolithic · Spanish Mediterranean region Introduction Communicated by F. -

Thomas James Connolly

Thomas James Connolly Archaeological Research Director Phone: 541-346-3031 (office) UO Museum of Natural and Cultural History 541-285-8267 (cell) & State Museum of Anthropology [email protected] 1224 University of Oregon http://natural-history.uoregon.edu/ Eugene, Oregon 97403-1224 Education Ph.D. 1986 University of Oregon. Department of Anthropology (Archaeology; Dissertation title: Cultural Stability and Change in the Prehistory of Southwest Oregon and Northern California) M.S. 1980 University of Oregon, Department of Anthropology (Archaeology). B.S. 1977 Moorhead State University (now Minnesota State University at Moorhead), Department of Sociology and Anthropology (Sociology, magna cum laude). Archaeological Employment 1986-present Director, Research Division, State Museum of Anthropology, Museum of Natural & Cultural History, University of Oregon, Eugene (Sr. Research Associate 1995-2008; Research Associate 1986-1995). 1984-86 Collections Specialist, State Museum of Anthropology, University of Oregon. 1983-86 Partner in BC/AD Consultants, a cultural resource consulting service. 1981-84 Research Assistant, State Museum of Anthropology, University of Oregon. 1983-79 Contract Archaeologist, Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon. 1976-86 Archaeological Technician, University of Oregon, University of North Dakota, University of Minnesota at Moorhead, Heritage Research Associates. Teaching Experience 1999-present Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon (primary affiliation with the UO Museum of Natural and Cultural History). Co-Instructor: Oregon Archaeology 2001-2010 University of Oregon Field Studies Center, Bend, Oregon. Courses taught: Oregon Archaeology, Archaeological Research Methods 1980-1981 Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon, Graduate Teaching Assistant 1977-1979 Teaching Substitute, Secondary Schools, Fargo School District, Fargo, North Dakota Publications: Books, Monographs, and Edited Volumes Aikens, C.