Radiocarbon Evidence Relating to Northern Great Basin Basketry Chronology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program of the 75Th Anniversary Meeting

PROGRAM OF THE 75 TH ANNIVERSARY MEETING April 14−April 18, 2010 St. Louis, Missouri THE ANNUAL MEETING of the Society for American Archaeology provides a forum for the dissemination of knowledge and discussion. The views expressed at the sessions are solely those of the speakers and the Society does not endorse, approve, or censor them. Descriptions of events and titles are those of the organizers, not the Society. Program of the 75th Anniversary Meeting Published by the Society for American Archaeology 900 Second Street NE, Suite 12 Washington DC 20002-3560 USA Tel: +1 202/789-8200 Fax: +1 202/789-0284 Email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.saa.org Copyright © 2010 Society for American Archaeology. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher. Program of the 75th Anniversary Meeting 3 Contents 4............... Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting Agenda 5……….….2010 Award Recipients 10.................Maps of the America’s Center 12 ................Maps of Renaissance Grand St. Louis 14 ................Meeting Organizers, SAA Board of Directors, & SAA Staff 15 .............. General Information 18. ............. Featured Sessions 20 .............. Summary Schedule 25 .............. A Word about the Sessions 27............... Program 161................SAA Awards, Scholarships, & Fellowships 167............... Presidents of SAA . 168............... Annual Meeting Sites 169............... Exhibit Map 170................Exhibitor Directory 180................SAA Committees and Task Forces 184………….Index of participants 4 Program of the 75th Anniversary Meeting Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting America’s Center APRIL 16, 2010 5 PM Call to Order Call for Approval of Minutes of the 2009 Annual Business Meeting Remarks President Margaret W. -

Fort Rock Cave: Assessing the Site’S Potential to Contribute to Ongoing Debates About How and When Humans Colonized the Great Basin

RETURN TO FORT ROCK CAVE: ASSESSING THE SITE’S POTENTIAL TO CONTRIBUTE TO ONGOING DEBATES ABOUT HOW AND WHEN HUMANS COLONIZED THE GREAT BASIN Thomas J. Connolly, Judson Byrd Finley, Geoffrey M. Smith, Dennis L. Jenkins, Pamela E. Endzweig, Brian L. O’Neill, and Paul W. Baxter Oregon’s Fort Rock Cave is iconic in respect to both the archaeology of the northern Great Basin and the history of debate about when the Great Basin was colonized. In 1938, Luther Cressman recovered dozens of sagebrush bark sandals from beneath Mt. Mazama ash that were later radiocarbon dated to between 10,500 and 9350 cal B.P. In 1970, Stephen Bedwell reported finding lithic tools associated with a date of more than 15,000 cal B.P., a date dismissed as unreasonably old by most researchers. Now, with evidence of a nearly 15,000-year-old occupation at the nearby Paisley Five Mile Point Caves, we returned to Fort Rock Cave to evaluate the validity of Bedwell’s claim, assess the stratigraphic integrity of remaining deposits, and determine the potential for future work at the site. Here, we report the results of additional fieldwork at Fort Rock Cave undertaken in 2015 and 2016, which supports the early Holocene occupation, but does not confirm a pre–10,500 cal B.P. human presence. La cueva de Fort Rock en Oregón es icónica por lo que representa para la arqueología de la parte norte de la Gran Cuenca y para la historia del debate sobre la primera ocupación de la Gran Cuenca. En 1938, Luther Cressman recuperó docenas de sandalias de corteza de artemisa debajo de una capa de cenizas del monte Mazama que fueron posteriormente fechadas por radiocarbono entre 10,500 y 9200 cal a.P. -

Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College Version June 20, 2012

1 Annotated Atlatl Bibliography John Whittaker Grinnell College version June 20, 2012 Introduction I began accumulating this bibliography around 1996, making notes for my own uses. Since I have access to some obscure articles, I thought it might be useful to put this information where others can get at it. Comments in brackets [ ] are my own comments, opinions, and critiques, and not everyone will agree with them. The thoroughness of the annotation varies depending on when I read the piece and what my interests were at the time. The many articles from atlatl newsletters describing contests and scores are not included. I try to find news media mentions of atlatls, but many have little useful info. There are a few peripheral items, relating to topics like the dating of the introduction of the bow, archery, primitive hunting, projectile points, and skeletal anatomy. Through the kindness of Lorenz Bruchert and Bill Tate, in 2008 I inherited the articles accumulated for Bruchert’s extensive atlatl bibliography (Bruchert 2000), and have been incorporating those I did not have in mine. Many previously hard to get articles are now available on the web - see for instance postings on the Atlatl Forum at the Paleoplanet webpage http://paleoplanet69529.yuku.com/forums/26/t/WAA-Links-References.html and on the World Atlatl Association pages at http://www.worldatlatl.org/ If I know about it, I will sometimes indicate such an electronic source as well as the original citation. The articles use a variety of measurements. Some useful conversions: 1”=2.54 -

0205683290.Pdf

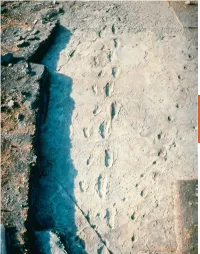

Hominin footprints preserved at Laetoli, Tanzania, are about 3.6 million years old. These individuals were between 3 and 4 feet tall when standing upright. For a close-up view of one of the footprints and further information, go to the human origins section of the website of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, www.mnh.si.edu/anthro/ humanorigins/ha/laetoli.htm. THE EVOLUTION OF HUMANITY AND CULTURE 2 the BIG questions v What do living nonhuman primates tell us about OUTLINE human culture? Nonhuman Primates and the Roots of Human Culture v Hominin Evolution to Modern What role did culture play Humans during hominin evolution? Critical Thinking: What Is Really in the Toolbox? v How has modern human Eye on the Environment: Clothing as a Thermal culture changed in the past Adaptation to Cold and Wind 12,000 years? The Neolithic Revolution and the Emergence of Cities and States Lessons Applied: Archaeology Findings Increase Food Production in Bolivia 33 Substantial scientific evidence indicates that modern hu- closest to humans and describes how they provide insights into mans have evolved from a shared lineage with primate ances- what the lives of the earliest human ancestors might have been tors between 4 and 8 million years ago. The mid-nineteenth like. It then turns to a description of the main stages in evolu- century was a turning point in European thinking about tion to modern humans. The last section covers the develop- human origins as scientific thinking challenged the biblical ment of settled life, agriculture, and cities and states. -

Dr. Brett R. Lenz

COLONIZER GEOARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST REGION A Dissertation DR. BRETT R. LENZ COLONIZER GEOARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST REGION, NORTH AMERICA Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester By Brett Reinhold Lenz Department of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester June 2011 1 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to Garreck, Haydn and Carver. And to Hank, for teaching me how rivers form. 2 Abstract This dissertation involves the development of a geologic framework applied to upper Pleistocene and earliest Holocene archaeological site discovery. It is argued that efforts to identify colonizer archaeological sites require knowledge of geologic processes, Quaternary stratigraphic detail and an understanding of basic soil science principles. An overview of Quaternary geologic deposits based on previous work in the region is presented. This is augmented by original research which presents a new, proposed regional pedostratigraphic framework, a new source of lithic raw material, the Beezley chalcedony, and details of a new cache of lithic tools with Paleoindian affinities made from this previously undescribed stone source. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The list of people who deserve my thanks and appreciation is large. First, to my parents and family, I give the greatest thanks for providing encouragement and support across many years. Without your steady support it would not be possible. Thanks Mom and Dad, Steph, Jen and Mellissa. To Dani and my sons, I appreciate your patience and support and for your love and encouragement that is always there. Due to a variety of factors, but mostly my own foibles, the research leading to this dissertation has taken place over a protracted period of time, and as a result, different stages of my personal development are likely reflected in it. -

Post-Glacial Fire History of Horsetail Fen and Human-Environment Interactions in the Teanaway Area of the Eastern Cascades, Washington

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU All Master's Theses Master's Theses Winter 2019 Post-Glacial Fire History of Horsetail Fen and Human-Environment Interactions in the Teanaway Area of the Eastern Cascades, Washington Serafina erriF Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Education Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Other Environmental Sciences Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Ferri, Serafina, "Post-Glacial Fire History of Horsetail Fen and Human-Environment Interactions in the Teanaway Area of the Eastern Cascades, Washington" (2019). All Master's Theses. 1124. https://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/etd/1124 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POST-GLACIAL FIRE HISTORY OF HORSETAIL FEN AND HUMAN-ENVIRONMENT INTERACTIONS IN THE TEANAWAY AREA OF THE EASTERN CASCADES, WASHINGTON __________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty Central Washington University ___________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Resource Management ___________________________________ by Serafina Ann Ferri February 2019 CENTRAL WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Graduate Studies -

Solving the Mystery of Chaco Canyon?

VIRTUALBANNER ARCHAEOLOGY BANNER • BANNER STUDYING • BANNER PREHISTORIC BANNER VIOLENCE BANNER • T •ALE BANNERS OF A NCIENT BANNER TEXTILE S american archaeologyWINTER 2012-13 a quarterly publication of The Archaeological Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 SOLVINGSOLVING THETHE MYMYSSTERYTERY OFOF CHACHACCOO CANYONCANYON?? $3.95 $3.95 WINTER 2012-13 americana quarterly publication of The Archaeological archaeology Conservancy Vol. 16 No. 4 COVER FEATURE 26 CHACO, THROUGH A DIFFERENT LENS BY MIKE TONER Southwest scholar Steve Lekson has taken an unconventional approach to solving the mystery of Chaco Canyon. 12 VIRTUALLY RECREATING THE PAST BY JULIAN SMITH Virtual archaeology has remarkable potential, but it also has some issues to resolve. 19 A ROAD TO THE PAST BY ALISON MCCOOK A dig resulting from a highway project is yielding insights into Delaware’s colonial history. 33 THE TALES OF ANCIENT TEXTILES BY PAULA NEELY Fabric artifacts are providing a relatively new line of evidence for archaeologists. 39 UNDERSTANDING PREHISTORIC VIOLENCE BY DAN FERBER Bioarchaeologists have gone beyond studying the manifestations of ancient violence to examining CHAZ EVANS the conditions that caused it. 26 45 new acquisition A TRAIL TO PREHISTORY The Conservancy saves a trailhead leading to an important Sinagua settlement. 46 new acquisition NORTHERNMOST CHACO CANYON OUTLIER TO BE PRESERVED Carhart Pueblo holds clues to the broader Chaco regional system. 48 point acquisition A GLIMPSE OF A MAJOR TRANSITION D LEVY R Herd Village could reveal information about the change from the Basketmaker III to the Pueblo I phase. RICHA 12 2 Lay of the Land 50 Field Notes 52 RevieWS 54 Expeditions 3 Letters 5 Events COVER: Pueblo Bonito is one of the great houses at Chaco Canyon. -

New Record of Terminal Pleistocene Elk/Wapiti (Cervus Canadensis) from Ohio, USA

2 TERMINAL PLEISTOCENE ELK FROM OHIO VOL. 121(2) New Record of Terminal Pleistocene Elk/Wapiti (Cervus canadensis) from Ohio, USA BRIAN G. REDMOND1, Department of Archaeology, Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Cleveland, OH, USA; DAVID L. DYER, Ohio History Connection, Columbus, OH, USA; and CHARLES STEPHENS, Sugar Creek Chapter, Archaeological Society of Ohio, Massillon, OH, USA. ABSTRACT. The earliest appearance of elk/wapiti (Cervus canadensis) in eastern North America is not thoroughly documented due to the small number of directly dated remains. Until recently, no absolute dates on elk bone older than 10,000 14C yr BP (11,621 to 11,306 calibrated years (cal yr) BP) were known from this region. The partial skeleton of the Tope Elk was discovered in 2017 during commercial excavation of peat deposits from a small bog in southeastern Medina County, Ohio, United States. Subsequent examination of the remains revealed the individual to be a robust male approximately 8.5 years old at death. The large size of this individual is compared with late Holocene specimens and suggests diminution of elk since the late Pleistocene. Two accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon assays on bone collagen samples taken from the scapula and metacarpal of this individual returned ages of 10,270 ± 30 14C yr BP (Beta-477478) (12,154 to 11,835 cal yr BP) and 10,260 ± 30 14C yr BP (Beta-521748) (12,144 to 11,830 cal yr BP), respectively. These results place Cervus canadensis in the terminal Pleistocene of the eastern woodlands and near the establishment of the mixed deciduous forest biome over much of the region. -

In Search of the First Americas

In Search of the First Americas Michael R. Waters Departments of Anthropology and Geography Center for the Study of the First Americans Texas A&M University Who were the first Americans? When did they arrive in the New World? Where did they come from? How did they travel to the Americas & settle the continent? A Brief History of Paleoamerican Archaeology Prior to 1927 People arrived late to the Americas ca. 6000 B.P. 1927 Folsom Site Discovery, New Mexico Geological Estimate in 1927 10,000 to 20,000 B.P. Today--12,000 cal yr B.P. Folsom Point Blackwater Draw (Clovis), New Mexico 1934 Clovis Discovery Folsom (Bison) Clovis (Mammoth) Ernst Antevs Geological estimate 13,000 to 14,000 B.P. Today 13,000 cal yr B.P. 1935-1990 Search continued for sites older than Clovis. Most sites did not stand up to scientific scrutiny. Calico Hills More Clovis sites were found across North America The Clovis First Model became entrenched. Pedra Furada Tule Springs Clovis First Model Clovis were the first people to enter the Americas -Originated from Northeast Asia -Entered the Americas by crossing the Bering Land Bridge and passing through the Ice Free Corridor around 13,600 cal yr B.P. (11,500 14C yr B.P.) -Clovis technology originated south of the Ice Sheets -Distinctive tools that are widespread -Within 800 years reached the southern tip of South America -Big game hunters that killed off the Megafauna Does this model still work? What is Clovis? • Culture • Era • Complex Clovis is an assemblage of distinctive tools that were made in a very prescribed way. -

New Research at Paisley Caves: Applying New Integrated Analytical Approaches to Understanding Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Site Formation Processes

Shillito L-M, Blong J, Jenkins D, Stafford TW, Whelton H, McDonough K, Bull I. New Research at Paisley Caves: Applying New Integrated Analytical Approaches to Understanding Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Site Formation Processes. PaleoAmerica 2018 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2017.1396167 Copyright: © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited DOI link to article: https://doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2017.1396167 Date deposited: 23/10/2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk PaleoAmerica A journal of early human migration and dispersal ISSN: 2055-5563 (Print) 2055-5571 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ypal20 New Research at Paisley Caves: Applying New Integrated Analytical Approaches to Understanding Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Site Formation Processes Lisa-Marie Shillito, John C. Blong, Dennis L. Jenkins, Thomas W. Stafford Jr, Helen Whelton, Katelyn McDonough & Ian D. Bull To cite this article: Lisa-Marie Shillito, John C. Blong, Dennis L. Jenkins, Thomas W. Stafford Jr, Helen Whelton, Katelyn McDonough & Ian D. Bull (2018): New Research at Paisley Caves: Applying New Integrated Analytical Approaches to Understanding Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Site Formation Processes, PaleoAmerica, DOI: 10.1080/20555563.2017.1396167 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/20555563.2017.1396167 © 2018 The Author(s). -

Christmas Valley

I D -1 P" Fort Rock State Park £D • O Q} Oregon's Back Country XT O O PT Fort Rock was formed some 5 to 6 million years CD • O <D Byways ago when volcanic material erupted through an S. 03 — < Bureau of Land Management The BLM's Back Country Byway program resulted existing lake in an explosive burst of steam and I 8 | | from a Presidential Commission study which molten rock, leaving behind a ring of material, or showed that 43 percent of Americans regard maar, as evidence of the initial explosive event. driving for pleasure as their favorite recreation CQ CD </) activity. For those with the time and desire to turn Town of Fort Rock O CD ^ Christmas off the beaten track onto a country road, Oregon's First settlement in the Ft. Rock area traces to CD GO 2. Back Country Byways provide access to a 1905. Basic travel services are provided. The -si diversity of landscapes and attractions just waiting Fort Rock Historical Society began work in 1989 O CO Valley to be discovered. BLM's byways will meet this on a museum to relate the history of the area. O demand for pleasure driving, enhance recreation Guide Supplement - Six miles east of Ft. Rock experiences, and better inform visitors about the the Byway continues due east on Lake County values of public lands. Road 5-12. Road 5-10 turns south toward Christmas Valley. At the end of the blacktop Christmas Valley Back paving the route turns north to follow road 5-12 as National Back a gravel road. -

Geoarchaeological Assessment of Horseshoe Cave (24RB1094, Rosebud County, Montana

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2012 Geoarchaeological Assessment of Horseshoe Cave (24RB1094, Rosebud County, Montana Norman Bernard Smyers The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smyers, Norman Bernard, "Geoarchaeological Assessment of Horseshoe Cave (24RB1094, Rosebud County, Montana" (2012). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 486. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/486 This Professional Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GEOARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF HORSESHOE CAVE (24RB1094), ROSEBUD COUNTY, MONTANA By Norman Bernard Smyers Master of Science, San Diego State University, San Diego, California, 1970 Bachelor of Science, California State University at Long Beach, California, 1967 Professional Paper Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology, Cultural Heritage The University of Montana Missoula, MT May 2012 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Associate Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr. Douglas MacDonald, Chair