Pictish Symbol Stones and Early Cross-Slabs from Orkney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![{PDF EPUB} a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.Com](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4988/pdf-epub-a-guide-to-prehistoric-and-viking-shetland-by-noel-fojut-a-guide-to-prehistoric-and-viking-shetland-fojut-noel-on-amazon-com-44988.webp)

{PDF EPUB} a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.Com

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut A guide to prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. A guide to prehistoric and Viking Shetland4/5(1)A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland: Fojut, Noel ...https://www.amazon.com/Guide-Prehistoric-Shetland...A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking ShetlandAuthor: Noel FojutFormat: PaperbackVideos of A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland By Noel Fojut bing.com/videosWatch video on YouTube1:07Shetland’s Vikings take part in 'Up Helly Aa' fire festival14K viewsFeb 1, 2017YouTubeAFP News AgencyWatch video1:09Shetland holds Europe's largest Viking--themed fire festival195 viewsDailymotionWatch video on YouTube13:02Jarlshof - prehistoric and Norse settlement near Sumburgh, Shetland1.7K viewsNov 16, 2016YouTubeFarStriderWatch video on YouTube0:58Shetland's overrun by fire and Vikings...again! | BBC Newsbeat884 viewsJan 31, 2018YouTubeBBC NewsbeatWatch video on Mail Online0:56Vikings invade the Shetland Isles to celebrate in 2015Jan 28, 2015Mail OnlineJay AkbarSee more videos of A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland By Noel FojutA Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland - Noel Fojut ...https://books.google.com/books/about/A_guide_to...A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland: Author: Noel Fojut: Edition: 3, illustrated: Publisher: Shetland Times, 1994: ISBN: 0900662913, 9780900662911: Length: 127 pages : Export Citation:... FOJUT, Noel. A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland. ... A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland FOJUT, Noel. 0 ratings by Goodreads. ISBN 10: 0900662913 / ISBN 13: 9780900662911. Published by Shetland Times, 1994, 1994. -

THE VIKINGS in ORKNEY James Graham-Campbell

THE VIKINGS IN ORKNEY James Graham-Campbell Introduction In recent years, it has been suggested that the first permanent Scandinavian presence in Orkney was not the result of forcible land-taking by Vikings, but came about instead through gradual penetration - a period which has been described as one of'informal' settlement (Morris 1985: 213; 1998: 83). Such would have involved a phase of co-existence, or even integration, between the native Picts and the earliest Norse settlers. This initial period, it is supposed, was then followed by 'a second, formal, settlement associated with the estab lishment of an earldom' (Morris 1998: 83 ), in the late 9'h century. The archaeological evidence advanced in support of the first 'period of overlap' is, however, open to alternative interpretation and, indeed, Alfred Smyth has com mented ( 1984: 145), in relation to the annalistic records of the earliest Viking attacks on Ireland, that these 'strongly suggest that the Norwegians did not gradually infiltrate the Northern Isles as farmers and fisherman and then sud denly tum nasty against their neighbours'. Others have supposed that the first phase of Norse settlement in Orkney would have involved, in the words of Buteux (1997: 263): 'ness-taking' (the fortifying of a headland by means of a cross-dyke) and the occupation of small off-shore islands. Crawford ( 1987: 46) argues that headland dykes on Orkney can be interpreted as indicating ness-taking. However many are equally likely to be prehistoric land boundaries, and no bases on either headlands or small islands have yet been positively identified. Buteux continues his discussion by observing, most pertinently, that: While this can not be taken as suggesting that such sites do not remain to be uncovered, the striking fact is that almost all identified Viking-period settlements in the Northern Isles are found overlying or immediately adjacent to sites which were occupied in the preceding Pictish period and which, furthermore, had frequently been settlements of some size and importance. -

Brough of Birsay Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC278 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90034) Taken into State care: 1933 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE BROUGH OF BIRSAY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office:Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office:Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH BROUGH OF BIRSAY BRIEF DESCRIPTION The monument comprises an area of Pictish to medieval settlement and ecclesiastical remains, situated on part of a small tidal island off the NW corner of Mainland Orkney. -

Theses Digitisation: This Is a Digitised

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] VOLUME 3 ( d a t a ) ter A R t m m w m m d geq&haphy 2 1 SHETLAND BROCKS Thesis presented in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor 6f Philosophy in the Facility of Arts, University of Glasgow, 1979 ProQuest Number: 10984311 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10984311 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Cruising the ISLANDS of ORKNEY

Cruising THE ISLANDS OF ORKNEY his brief guide has been produced to help the cruising visitor create an enjoyable visit to TTour islands, it is by no means exhaustive and only mentions the main and generally obvious anchorages that can be found on charts. Some of the welcoming pubs, hotels and other attractions close to the harbour or mooring are suggested for your entertainment, however much more awaits to be explored afloat and many other delights can be discovered ashore. Each individual island that makes up the archipelago offers a different experience ashore and you should consult “Visit Orkney” and other local guides for information. Orkney waters, if treated with respect, should offer no worries for the experienced sailor and will present no greater problem than cruising elsewhere in the UK. Tides, although strong in some parts, are predictable and can be used to great advantage; passage making is a delight with the current in your favour but can present a challenge when against. The old cruising guides for Orkney waters preached doom for the seafarer who entered where “Dragons and Sea Serpents lie”. This hails from the days of little or no engine power aboard the average sailing vessel and the frequent lack of wind amongst tidal islands; admittedly a worrying combination when you’ve nothing but a scrap of canvas for power and a small anchor for brakes! Consult the charts, tidal guides and sailing directions and don’t be afraid to ask! You will find red “Visitor Mooring” buoys in various locations, these are removed annually over the winter and are well maintained and can cope with boats up to 20 tons (or more in settled weather). -

REVIEW Edition

JUNE ROUSAY, EGILSAY & WYRE 2009 Internet REVIEW Edition WHAT’S ON IN JUNE Tuesday, 2nd. ROUSAY REGATTA & WATERSPORTS DAY InnQUIZition at 8.00 p.m. TH. at The Taversoe SATURDAY, 27 JUNE Thursday, 4th. As the date for the Regatta is again fast coming upon us, we must Parent Council Meeting at the School - 2 p.m. get things more organised about the Pier this year. First, we need helpers to make the day a success, strong men and Saturday, 6th. women to look after some of the sports, such as the pillow fights; SWRI hosting Holm Visitors from 11.00 a.m. tight rope; do-nut challenge; greasy pole; etc.- to organise a time for starting them and keeping records to determine the winners. A Sunday, 7th. different person for each sport would be really good. We also - Church Service 11.30 - Gun Club at Quoy need people to help with the stall, games and entertainment. We Grinnie, 2.00 p.m. also need donations of small cakes and tablet for a cake stall, so Tuesday, 9th any help with this would be much appreciated. School Skate Park Setup at To sort out the organisation necessary to make this a great day for 11.30 a.m. all taking part, as well as raising funds for the RNLI, there will be Thursday, June 11th. Tommy’s Photo Show at A MEETING AT THE PIER RESTAURANT the Church Centre 7.30 p.m TH. ON FRIDAY, 19 JUNE AT 8.00 P.M. Sunday, 14th. Church Service 11.30 We need your help and support to sort out the Games; Stalls; Tuesday, 16th. -

Modern Rune Carving in Northern Scotland. Futhark 8

Modern Rune Carving in Northern Scotland Andrea Freund and Ragnhild Ljosland (University of the Highlands and Islands) Abstract This article discusses modern runic inscriptions from Orkney and Caithness. It presents various examples, some of which were previously considered “genuine”, and reveals that OR 13 Skara Brae is of modern provenance. Other examples from the region can be found both on boulders or in bedrock and in particular on ancient monuments ranging in date from the Neolithic to the Iron Age. The terminology applied to modern rune carving, in particular the term “forgery”, is examined, and the phenomenon is considered in relation to the Ken sington runestone. Comparisons with modern rune carving in Sweden are made and suggestions are presented as to why there is such an abundance of recently carved inscriptions in Northern Scotland. Keywords: Scotland, Orkney, Caithness, modern runic inscriptions, modern rune carving, OR 13 Skara Brae, Kensington runestone Introduction his article concerns runic inscriptions from Orkney and Caithness Tthat were, either demonstrably or arguably, made in the modern period. The objective is twofold: firstly, the authors aim to present an inventory of modern inscriptions currently known to exist in Orkney and Caith ness. Secondly, they intend to discuss the concept of runic “forgery”. The question is when terms such as “fake” or “forgery” are helpful in de scribing a modern runic inscription, and when they are not. Included in the inventory are only those inscriptions which may, at least to an untrained eye, be mistaken for premodern. Runes occurring for example on jewellery, souvenirs, articles of clothing, in logos and the Freund, Andrea, and Ragnhild Ljosland. -

Download Date 26/09/2021 13:38:25

Settlement and landscape in the Northern Isles; a multidisciplinary approach. Archaeological research into long term settlements and thier associated arable fields from the Neolithic to the Norse periods. Item Type Thesis Authors Dockrill, Stephen J. Rights <a rel="license" href="http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/3.0/"><img alt="Creative Commons License" style="border-width:0" src="http://i.creativecommons.org/l/by- nc-nd/3.0/88x31.png" /></a><br />The University of Bradford theses are licenced under a <a rel="license" href="http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/">Creative Commons Licence</a>. Download date 26/09/2021 13:38:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10454/6334 University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. Settlement and Landscape in the Northern Isles; a Multidisciplinary Approach Archaeological research into long term settlements and their associated arable fields from the Neolithic to the Norse periods Volume 1 of 2 Stephen James DOCKRILL Doctor of Philosophy by Published Work Division of Archaeological, Geographical and Environmental Sciences University of Bradford 2013 Abstract The research contained in these papers embodies both results from direct archaeological investigation and also the development of techniques (geophysical, chronological and geoarchaeological) in order to understand long- term settlements and their associated landscapes in Orkney and Shetland. Central to this research has been the study of soil management strategies of arable plots surrounding settlements from the Neolithic to the Iron Age. -

The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 5 Print Reference: Pages 561-572 Article 43 2003 The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island Lawson L. Schroeder Philip L. Schroeder Bryan College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Schroeder, Lawson L. and Schroeder, Philip L. (2003) "The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5 , Article 43. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol5/iss1/43 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ANCIENT STANDING STONES, VILLAGES AND TOMBS FOUND ON THE ORKNEY ISLANDS LAWSON L. SCHROEDER, D.D.S. PHILIP L. SCHROEDER 5889 MILLSTONE RUN BRYAN COLLEGE STONE MOUNTAIN, GA 30087 P. O. BOX 7484 DAYTON, TN 37321-7000 KEYWORDS: Orkney Islands, ancient stone structures, Skara Brae, Maes Howe, broch, Ring of Brodgar, Standing Stones of Stenness, dispersion, Babel, famine, Ice Age ABSTRACT The Orkney Islands make up an archipelago north of Scotland. -

University of Bradford Ethesis

University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. THE NEOLITHIC AND LATE IRON AGE POTTERY FROM POOL, SANDAY, ORKNEY An archaeological and technological consideration of coarse pottery manufacture at the Neolithic and Late Iron Age site of Pool, Orkney, incorporating X-Ray Fluorescence, Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometric and Petrological Analyses 2 Volumes Volume 1 Ann MACSWEEN submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeological Sciences University of Bradford 1990 ABSTRACT Ann MacSween The Neolithic and Late Iron Age Pottery from Pool, Sanday, Orkney: An archaeological and technological consideration of coarse pottery manufacture at the Iron Age site of Pool, Orkney, incorporating X-Ray Fluorescence, Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometric and Petrological Analyses Key Words: Neolithic; Iron Age; Orkney; pottery; X-ray Fluorescence; Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometry; Petrological Analysis The Neolithic and late Iron Age pottery from the settlement site of Pool, Sanday, Orkney, was studied on two levels. Firstly, a morphological and tech- nological study was carried out to establish a se- quence for the site. Secondly an assessment was made of the usefulness of X-ray Fluorescence Analysis, In- ductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometry and Petrological analysis to coarse ware studies, using the Pool assem- blage as a case study. Recording of technological and typological attributes allowed three phases of Neolithic pottery to be iden- tified. The earliest phase included sherds of Unstan Ware. -

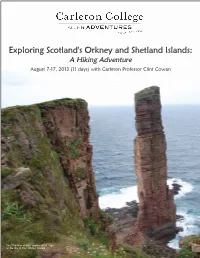

With Carleton Professor Clint Cowan

August 7-17, 2013 (11 days) with Carleton Professor Clint Cowan The "Old Man of Hoy" stands 450 ft. high on the Isle of Hoy, Orkney Islands. Dear Carleton College Alumni and Friends, I invite you to join Carleton College geologist Clint Cowan ’83 on this unique new hiking tour in Scotland’s little-visited Orkney and Shetland Islands! This is the perfect opportunity to explore on foot Scotland’s Northern Isles' amazing wealth of geological and archaeological sites. Their rocks tell the whole story, spanning almost three billion years. On Shet- land you will walk on an ancient ocean floor, explore an extinct volcano, and stroll across shifting sands. In contrast, Orkney is made up largely of sedimentary rocks, one of the best collections of these sediments to be seen anywhere in the world. Both archipelagoes also have an amazing wealth of archaeological sites dating back 5,000 years. This geological and archaeological saga is worth the telling, and nowhere else can the evidence be seen in more glorious a setting. Above & Bottom: The archaeological site of Jarlshof, dat- ing back to 2500 B.C. Below: A view of the Atlantic from This active land tour features daily hikes that are easy to moderate the northern Shetland island of Unst. in difficulty, so to fully enjoy and visit all the sites on this itinerary one should be in good walking condition (and, obviously, enjoy hiking!). Highlights include: • The “Heart of Neolithic Orkney,” inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1999, including the chambered tomb of Maeshowe, estimated to have been constructed around 2700 B.C.; the 4,000 year old Ring of Brodgar, one of Europe’s finest Neolithic monu- ments; Skara Brae settlement; and associated monuments and stone settings. -

Kingdom of Strathclyde from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Kingdom of Strathclyde From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Strathclyde (lit. "Strath of the Clyde"), originally Brythonic Ystrad Clud, was one of the early medieval kingdoms of the Kingdom of Strathclyde Celtic people called the Britons in the Hen Ogledd, the Teyrnas Ystrad Clut Brythonic-speaking parts of what is now southern Scotland and northern England. The kingdom developed during the ← 5th century–11th → post-Roman period. It is also known as Alt Clut, the Brythonic century name for Dumbarton Rock, the medieval capital of the region. It may have had its origins with the Damnonii people of Ptolemy's Geographia. The language of Strathclyde, and that of the Britons in surrounding areas under non-native rulership, is known as Cumbric, a dialect or language closely related to Old Welsh. Place-name and archaeological evidence points to some settlement by Norse or Norse–Gaels in the Viking Age, although to a lesser degree than in neighbouring Galloway. A small number of Anglian place-names show some limited settlement by incomers from Northumbria prior to the Norse settlement. Due to the series of language changes in the area, it is not possible to say whether any Goidelic settlement took place before Gaelic was introduced in the High Middle Ages. After the sack of Dumbarton Rock by a Viking army from Dublin in 870, the name Strathclyde comes into use, perhaps reflecting a move of the centre of the kingdom to Govan. In the same period, it was also referred to as Cumbria, and its inhabitants as Cumbrians. During the High Middle Ages, the area was conquered by the Kingdom of Alba, becoming part of The core of Strathclyde is the strath of the River Clyde.