THE VIKINGS in ORKNEY James Graham-Campbell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3 St Magnus Earl of Orkney

UHI Research Database pdf download summary Storyways Gibbon, Sarah Jane; Moore, James Published in: Open Archaeology Publication date: 2019 Publisher rights: © 2019 Sarah Jane Gibbon et al., published by De Gruyter. The re-use license for this item is: CC BY The Document Version you have downloaded here is: Peer reviewed version The final published version is available direct from the publisher website at: 10.1515/opar-2019-0016 Link to author version on UHI Research Database Citation for published version (APA): Gibbon, S. J., & Moore, J. (2019). Storyways: Visualising Saintly Impact in a North Atlantic Maritime Landscape. Open Archaeology, 5(1), 235-262. https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2019-0016 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the UHI Research Database are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights: 1) Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the UHI Research Database for the purpose of private study or research. 2) You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain 3) You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the UHI Research Database Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details; we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 Open Archaeology 2019; 5: 235–262 Original Study Sarah Jane Gibbon*, James Moore Storyways: Visualising Saintly Impact in a North Atlantic Maritime Landscape https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2019-0016 Received February 28, 2019; accepted May 17, 2019 Abstract: This paper presents a new methodological approach and theorising framework which visualises intangible landscapes. -

![{PDF EPUB} a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.Com](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4988/pdf-epub-a-guide-to-prehistoric-and-viking-shetland-by-noel-fojut-a-guide-to-prehistoric-and-viking-shetland-fojut-noel-on-amazon-com-44988.webp)

{PDF EPUB} a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut a Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.Com

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland by Noel Fojut A guide to prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. A guide to prehistoric and Viking Shetland4/5(1)A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland: Fojut, Noel ...https://www.amazon.com/Guide-Prehistoric-Shetland...A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland [Fojut, Noel] on Amazon.com. *FREE* shipping on qualifying offers. A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking ShetlandAuthor: Noel FojutFormat: PaperbackVideos of A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland By Noel Fojut bing.com/videosWatch video on YouTube1:07Shetland’s Vikings take part in 'Up Helly Aa' fire festival14K viewsFeb 1, 2017YouTubeAFP News AgencyWatch video1:09Shetland holds Europe's largest Viking--themed fire festival195 viewsDailymotionWatch video on YouTube13:02Jarlshof - prehistoric and Norse settlement near Sumburgh, Shetland1.7K viewsNov 16, 2016YouTubeFarStriderWatch video on YouTube0:58Shetland's overrun by fire and Vikings...again! | BBC Newsbeat884 viewsJan 31, 2018YouTubeBBC NewsbeatWatch video on Mail Online0:56Vikings invade the Shetland Isles to celebrate in 2015Jan 28, 2015Mail OnlineJay AkbarSee more videos of A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland By Noel FojutA Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland - Noel Fojut ...https://books.google.com/books/about/A_guide_to...A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland: Author: Noel Fojut: Edition: 3, illustrated: Publisher: Shetland Times, 1994: ISBN: 0900662913, 9780900662911: Length: 127 pages : Export Citation:... FOJUT, Noel. A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland. ... A Guide to Prehistoric and Viking Shetland FOJUT, Noel. 0 ratings by Goodreads. ISBN 10: 0900662913 / ISBN 13: 9780900662911. Published by Shetland Times, 1994, 1994. -

Pictish Symbol Stones and Early Cross-Slabs from Orkney

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 144 (2014), PICTISH169–204 SYMBOL STONES AND EARLY CROSS-SLABS FROM ORKNEY | 169 Pictish symbol stones and early cross-slabs from Orkney Ian G Scott* and Anna Ritchie† ABSTRACT Orkney shared in the flowering of interest in stone carving that took place throughout Scotland from the 7th century AD onwards. The corpus illustrated here includes seven accomplished Pictish symbol- bearing stones, four small stones incised with rough versions of symbols, at least one relief-ornamented Pictish cross-slab, thirteen cross-slabs (including recumbent slabs), two portable cross-slabs and two pieces of church furniture in the form of an altar frontal and a portable altar slab. The art-historical context for this stone carving shows close links both with Shetland to the north and Caithness to the south, as well as more distant links with Iona and with the Pictish mainland south of the Moray Firth. The context and function of the stones are discussed and a case is made for the existence of an early monastery on the island of Flotta. While much has been written about the Picts only superb building stone but also ideal stone for and early Christianity in Orkney, illustration of carving, and is easily accessible on the foreshore the carved stones has mostly taken the form of and by quarrying. It fractures naturally into flat photographs and there is a clear need for a corpus rectilinear slabs, which are relatively soft and can of drawings of the stones in related scales in easily be incised, pecked or carved in relief. -

Brough of Birsay Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC278 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90034) Taken into State care: 1933 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE BROUGH OF BIRSAY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office:Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office:Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH BROUGH OF BIRSAY BRIEF DESCRIPTION The monument comprises an area of Pictish to medieval settlement and ecclesiastical remains, situated on part of a small tidal island off the NW corner of Mainland Orkney. -

Wayneflete Tower, Esher, Surrey

Wessex Archaeology Wayneflete Tower, Esher, Surrey. Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Ref: 59472.01 March 2006 Wayneflete Tower, Esher, Surrey Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results Prepared on behalf of Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON SW1 8QP By Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB Report reference: 59472.01 March 2006 © Wessex Archaeology Limited 2006, all rights reserved Wessex Archaeology Limited is a Registered Charity No. 287786 Contents Summary Acknowledgements 1 BACKGROUND..................................................................................................5 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................5 1.2 Description of the Site................................................................................5 1.3 Historical Background...............................................................................5 1.4 Previous Archaeological Work ...............................................................12 2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES...............................................................................13 3 METHODS.........................................................................................................14 3.1 Introduction..............................................................................................14 3.2 Dendrochronological Survey...................................................................14 3.3 Geophysical Survey..................................................................................14 -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Cruising the ISLANDS of ORKNEY

Cruising THE ISLANDS OF ORKNEY his brief guide has been produced to help the cruising visitor create an enjoyable visit to TTour islands, it is by no means exhaustive and only mentions the main and generally obvious anchorages that can be found on charts. Some of the welcoming pubs, hotels and other attractions close to the harbour or mooring are suggested for your entertainment, however much more awaits to be explored afloat and many other delights can be discovered ashore. Each individual island that makes up the archipelago offers a different experience ashore and you should consult “Visit Orkney” and other local guides for information. Orkney waters, if treated with respect, should offer no worries for the experienced sailor and will present no greater problem than cruising elsewhere in the UK. Tides, although strong in some parts, are predictable and can be used to great advantage; passage making is a delight with the current in your favour but can present a challenge when against. The old cruising guides for Orkney waters preached doom for the seafarer who entered where “Dragons and Sea Serpents lie”. This hails from the days of little or no engine power aboard the average sailing vessel and the frequent lack of wind amongst tidal islands; admittedly a worrying combination when you’ve nothing but a scrap of canvas for power and a small anchor for brakes! Consult the charts, tidal guides and sailing directions and don’t be afraid to ask! You will find red “Visitor Mooring” buoys in various locations, these are removed annually over the winter and are well maintained and can cope with boats up to 20 tons (or more in settled weather). -

Mick Aston Archaeology Fund Supported by Historic England and Cadw

Mick Aston Archaeology Fund Supported by Historic England and Cadw Mick Aston’s passion for involving people in archaeology is reflected in the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund. His determination to make archaeology publicly accessible was realised through his teaching, work on Time Team, and advocating community projects. The Mick Aston Archaeology Fund is therefore intended to encourage voluntary effort in making original contributions to the study and care of the historic environment. Please note that the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund is currently open to applicants carrying out work in England and Wales only. Historic Scotland run a similar scheme for projects in Scotland and details can be found at: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/index/heritage/grants/grants-voluntary-sector- funding.htm. How does the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund work? Voluntary groups and societies, but also individuals, are challenged to put forward proposals for innovative projects that will say something new about the history and archaeology of local surroundings, and thus inform their future care. Proposals will be judged by a panel on their intrinsic quality, and evidence of capacity to see them through successfully. What is the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund panel looking for? First and foremost, the panel is looking for original research. Awards can be to support new work, or to support the completion of research already in progress, for example by paying for a specific piece of analysis or equipment. Projects which work with young people or encourage their participation are especially encouraged. What can funding be used for? In principle, almost anything that is directly related to the actual undertaking of a project. -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

Ferry Timetables

1768 Appendix 1. www.orkneyferries.co.uk GRAEMSAY AND HOY (MOANESS) EFFECTIVE FROM 24 SEPTEMBER 2018 UNTIL 4 MAY 2019 Our service from Stromness to Hoy/Graemsay is a PASSENGER ONLY service. Vehicles can be carried by prior arrangement to Graemsay on the advertised cargo sailings. Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Stromness dep 0745 0745 0745 0745 0745 0930 0930 Hoy (Moaness) dep 0810 0810 0810 0810 0810 1000 1000 Graemsay dep 0825 0825 0825 0825 0825 1015 1015 Stromness dep 1000 1000 1000 1000 1000 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1030 1030 1030 1030 1030 Graemsay dep 1045 1045 1045 1045 1045 Stromness dep 1200A 1200A 1200A Graemsay dep 1230A 1230A 1230A Hoy (Moaness) dep 1240A 1240A 1240A Stromness dep 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 1600 Graemsay dep 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 1615 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 1630 Stromness dep 1745 1745 1745 1745 1745 Graemsay dep 1800 1800 1800 1800 1800 Hoy (Moaness) dep 1815 1815 1815 1815 1815 Stromness dep 2130 Graemsay dep 2145 Hoy (Moaness) dep 2200 A Cargo Sailings will have limitations on passenger numbers therefore booking is advisable. These sailings may be delayed due to cargo operations. Notes: 1. All enquires must be made through the Kirkwall Office. Telephone: 01856 872044. 2. Passengers are requested to be available for boarding 5 minutes before departure. 3. Monday cargo to be booked by 1600hrs on previous Friday otherwise all cargo must be booked before 1600hrs the day before sailing. Cargo must be delivered to Stromness Pier no later than 1100hrs on the day of sailing. -

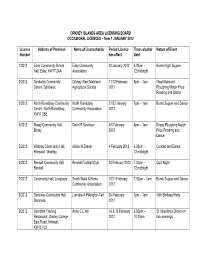

Summary Register of Occasional Licences

ORKNEY ISLANDS AREA LICENSING BOARD OCCASIONAL LICENCES – from 1 JANUARY 2012 Licence Address of Premises Name of Licenceholder Period Licence Times alcohol Nature of Event Number has effect Sold 1/2012 Eday Community School Eday Community 28 January 2012 6.30pm – Burns Night Supper Hall, Eday, KW17 2AA Association 12 midnight 2/2012 Sandwick Community Orkney West Mainland 11/12 February 8pm – 1am West Mainland Centre, Sandwick Agricultural Society 2012 Ploughing Match Prize Reading and Dance 3/2012 North Ronaldsay Community North Ronaldsay 21/22 January 7pm – 1am Burns Supper and Dance Centre, North Ronaldsay, Community Association 2012 KW17 2BE 4/2012 Birsay Community Hall, David R Davidson 4/5 February 8pm – 1am Birsay Ploughing Match Birsay 2012 Prize Reading and Dance 5/2012 Westray Community Hall, Alison M Drever 4 February 2012 6.30pm – Concert and Dance Pierowall, Westray 12 midnight 6/2012 Rendall Community Hall, Rendall Football Club 24 February 2012 7.30pm – Quiz Night Rendall 12 midnight 7/2012 Community Hall, Longhope South Walls & Brims 10/11 February 7.30pm – 1am Burns Supper and Dance Community Association 2012 8/2012 Stenness Community Hall, Lorraine A Pilkington-Tait 3/4 February 7pm – 1am 50th Birthday Party Stenness 2012 9/2012 Overblikk Training Anne C L Hill 14 & 16 February 6.30pm – St Valentines Dinner on Restaurant, Orkney College, 2012 10.30pm two evenings East Road, Kirkwall, KW15 1LX 10/2012 Deerness Community Gareth L Crichton 3/4 March 2012 8pm – 1am Concert and Dance Centre, Deerness, KW17 2QH 11/2012 Orphir -

Northern Isles Ferry Services

Item: 11 Development and Infrastructure Committee: 5 June 2018. Northern Isles Ferry Services. Report by Executive Director of Development and Infrastructure. 1. Purpose of Report To consider the specification for the future Northern Isles Ferry Services Contract. 2. Recommendations The Committee is invited to note: 2.1. That, in 2016, Transport Scotland appointed consultants, Peter Brett Associates, to carry out a proportionate appraisal of the Northern Isles Ferry Services, prior to drafting the future Northern Isles Ferry Services specifications. 2.2. That, as part of the appraisal process, Peter Brett Associates consulted with residents and key stakeholders, Transport Scotland, Highlands and Islands Enterprise, HITRANS, ZETRANS, Orkney Islands Council and Shetland Islands Council. 2.3. Key points from the Appraisal of Options for the Specification of the 2018 Northern Isles Ferry Services Final Report, summarised in section 4 of this report. 2.4. That, although the new Northern Isles Ferry Services contract was due to commence on 1 April 2018, the existing contract has been extended until October 2019 to consider the service specification in more detail and how the services should be procured in the future. It is recommended: 2.5. That the principles, attached as Appendix 2 to this report, be established, as the baseline position for the Council, to negotiate with the Scottish Government in respect of the contract specification for future provision of Northern Isles Ferry Services. Page 1. 2.6. That the Executive Director of Development and Infrastructure, in consultation with the Leader and Depute Leader and the Chair and Vice Chair of the Development and Infrastructure Committee, should engage with the Scottish Government, with the aim of securing the most efficient and best quality outcome for Orkney for future Northern Isles Ferry Services, by evolving the baseline principles referred to at paragraph 2.5 above.