Modern Rune Carving in Northern Scotland. Futhark 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pictish Symbol Stones and Early Cross-Slabs from Orkney

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 144 (2014), PICTISH169–204 SYMBOL STONES AND EARLY CROSS-SLABS FROM ORKNEY | 169 Pictish symbol stones and early cross-slabs from Orkney Ian G Scott* and Anna Ritchie† ABSTRACT Orkney shared in the flowering of interest in stone carving that took place throughout Scotland from the 7th century AD onwards. The corpus illustrated here includes seven accomplished Pictish symbol- bearing stones, four small stones incised with rough versions of symbols, at least one relief-ornamented Pictish cross-slab, thirteen cross-slabs (including recumbent slabs), two portable cross-slabs and two pieces of church furniture in the form of an altar frontal and a portable altar slab. The art-historical context for this stone carving shows close links both with Shetland to the north and Caithness to the south, as well as more distant links with Iona and with the Pictish mainland south of the Moray Firth. The context and function of the stones are discussed and a case is made for the existence of an early monastery on the island of Flotta. While much has been written about the Picts only superb building stone but also ideal stone for and early Christianity in Orkney, illustration of carving, and is easily accessible on the foreshore the carved stones has mostly taken the form of and by quarrying. It fractures naturally into flat photographs and there is a clear need for a corpus rectilinear slabs, which are relatively soft and can of drawings of the stones in related scales in easily be incised, pecked or carved in relief. -

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide

Water Safety Policy in Scotland —A Guide 2 Introduction Scotland is surrounded by coastal water – the North Sea, the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. In addition, there are also numerous bodies of inland water including rivers, burns and about 25,000 lochs. Being safe around water should therefore be a key priority. However, the management of water safety is a major concern for Scotland. Recent research has found a mixed picture of water safety in Scotland with little uniformity or consistency across the country.1 In response to this research, it was suggested that a framework for a water safety policy be made available to local authorities. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) has therefore created this document to assist in the management of water safety. In order to support this document, RoSPA consulted with a number of UK local authorities and organisations to discuss policy and water safety management. Each council was asked questions around their own area’s priorities, objectives and policies. Any policy specific to water safety was then examined and analysed in order to help create a framework based on current practice. It is anticipated that this framework can be localised to each local authority in Scotland which will help provide a strategic and consistent national approach which takes account of geographical areas and issues. Water Safety Policy in Scotland— A Guide 3 Section A: The Problem Table 1: Overall Fatalities 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2010 2011 2012 2013 Data from National Water Safety Forum, WAID database, July 14 In recent years the number of drownings in Scotland has remained generally constant. -

Language and Runes

Language andRunes Extracts of Swarkestone runic verse These dialects were spoken across what are from The now Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, and were in Ransome of Egill the Scald taken to Iceland when the Vikings settled there. Derbyshire and The Dying Ode of Regner Modern Icelandic is the closest surviving form combines Lodbrog on the title page of this medieval tongue; many Icelanders today the Old of their first English can still easily enjoy the medieval Icelandic Norse translation. Thomas sagas of the 12th-14th centuries in their original personal Percy, Five written form. name Pieces of Runic Poetry Swerkir with the Old English Translated from Anglo-Saxons spoke Old English, the ancestor Pp 1-2 from Magnús Ólafsson’s the Islandic element -tun (meaning ‘farm’ Old Icelandic dictionary with runic Language to our modern language. Old English was headwords and Latin definitions. (London or ‘homestead’), suggesting Magnús Ólafsson, Specimen lexici 1763). another Germanic language, with close kinship runici, obscuriorum qvarundam vocum, Eiríkur perhaps that a Viking took qvae in priscis occurrunt historiis & Benedikz to Old Norse, so it is plausible that Old poëtis danicis (Copenhagen 1650) Icelandic over an Anglo-Saxon farm. Special Collection Oversize PD2093.W6 Collection English and Old Norse speakers could, to a PT7245.E5 certain extent, understand one another. Early The Scandinavians also brought their system medieval Scandinavians had a notable effect on of writing with them: runes. The runic the development of modern English: words alphabet the Viking settlers employed is such as skirt, sky, window, and egg are all derived known as the Younger Futhark and consists from Old Norse. -

Further Studies of a Staggered Hybrid Zone in Musmusculus Domesticus (The House Mouse)

Heredity 71 (1993) 523—531 Received 26 March 1993 Genetical Society of Great Britain Further studies of a staggered hybrid zone in Musmusculus domesticus (the house mouse) JEREMYB. SEARLE, YOLANDA NARAIN NAVARRO* & GUILA GANEMI Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS,U.K. Inthe extreme north-east of Scotland (near the village of Joim o'Groats) there is a small karyotypic race of house mouse (2n= 32), characterized by four metacentric chromosomes 4.10, 9.12, 6.13 and 11.14. We present new data on the hybrid zone between this form and the standard race (2n =40)and show an association between race and habitat. In a transect south of John o'Groats we demonstrate that the dines for arm combinations 4.10 and 9.12 are staggered relative to the dines for 6.13 and 11.14, confirming previous data collected along an east—west transect (Searle, 1991). There are populations within the John o'Groats—standard hybrid zone dominated by individuals with 36 chromosomes (homozygous for 4.10 and 9.12), which may represent a novel karyotypic form that has arisen within the zone. Alternatively the type with 36 chromosomes may have been the progenitor of the John o'Groats race. Additional cytogenetic interest is provided by the occur- rence of a homogeneous staining region on one or both copies of chromosome 1 in some mice from the zone. Keywords:chromosomalvariation, hybrid zones, Mus musculus domesticus, Robertsonian fusions, staggered dines. Introduction (Rb) fusion of two ancestral acrocentrics with, for Thestandard karyotype of the house mouse consists of instance, metacentric 4.10 derived by fusion of acro- 40 acrocentric chromosomes. -

The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 5 Print Reference: Pages 561-572 Article 43 2003 The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island Lawson L. Schroeder Philip L. Schroeder Bryan College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Schroeder, Lawson L. and Schroeder, Philip L. (2003) "The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5 , Article 43. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol5/iss1/43 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ANCIENT STANDING STONES, VILLAGES AND TOMBS FOUND ON THE ORKNEY ISLANDS LAWSON L. SCHROEDER, D.D.S. PHILIP L. SCHROEDER 5889 MILLSTONE RUN BRYAN COLLEGE STONE MOUNTAIN, GA 30087 P. O. BOX 7484 DAYTON, TN 37321-7000 KEYWORDS: Orkney Islands, ancient stone structures, Skara Brae, Maes Howe, broch, Ring of Brodgar, Standing Stones of Stenness, dispersion, Babel, famine, Ice Age ABSTRACT The Orkney Islands make up an archipelago north of Scotland. -

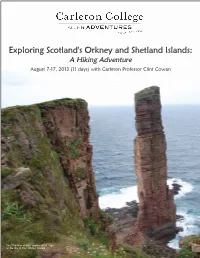

With Carleton Professor Clint Cowan

August 7-17, 2013 (11 days) with Carleton Professor Clint Cowan The "Old Man of Hoy" stands 450 ft. high on the Isle of Hoy, Orkney Islands. Dear Carleton College Alumni and Friends, I invite you to join Carleton College geologist Clint Cowan ’83 on this unique new hiking tour in Scotland’s little-visited Orkney and Shetland Islands! This is the perfect opportunity to explore on foot Scotland’s Northern Isles' amazing wealth of geological and archaeological sites. Their rocks tell the whole story, spanning almost three billion years. On Shet- land you will walk on an ancient ocean floor, explore an extinct volcano, and stroll across shifting sands. In contrast, Orkney is made up largely of sedimentary rocks, one of the best collections of these sediments to be seen anywhere in the world. Both archipelagoes also have an amazing wealth of archaeological sites dating back 5,000 years. This geological and archaeological saga is worth the telling, and nowhere else can the evidence be seen in more glorious a setting. Above & Bottom: The archaeological site of Jarlshof, dat- ing back to 2500 B.C. Below: A view of the Atlantic from This active land tour features daily hikes that are easy to moderate the northern Shetland island of Unst. in difficulty, so to fully enjoy and visit all the sites on this itinerary one should be in good walking condition (and, obviously, enjoy hiking!). Highlights include: • The “Heart of Neolithic Orkney,” inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1999, including the chambered tomb of Maeshowe, estimated to have been constructed around 2700 B.C.; the 4,000 year old Ring of Brodgar, one of Europe’s finest Neolithic monu- ments; Skara Brae settlement; and associated monuments and stone settings. -

Housing Application Guide Highland Housing Register

Housing Application Guide Highland Housing Register This guide is to help you fill in your application form for Highland Housing Register. It also gives you some information about social rented housing in Highland, as well as where to find out more information if you need it. This form is available in other formats such as audio tape, CD, Braille, and in large print. It can also be made available in other languages. Contents PAGE 1. About Highland Housing Register .........................................................................................................................................1 2. About Highland House Exchange ..........................................................................................................................................2 3. Contacting the Housing Option Team .................................................................................................................................2 4. About other social, affordable and supported housing providers in Highland .......................................................2 5. Important Information about Welfare Reform and your housing application ..............................................3 6. Proof - what and why • Proof of identity ...............................................................................................................................4 • Pregnancy ...........................................................................................................................................5 • Residential access to children -

P898: the Barrett Family Collection

P898: The Barrett Family Collection RECORDS’ IDENTITY STATEMENT Reference number: P898 Alternative reference number: Title: The Barret Family Collection Dates of creation: 1898 - 2015 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 7 linear meters Format: Paper, Wood, Glass, fabrics, alloys RECORDS’ CONTEXT Name of creators: Administrative history: Custodial history: Deposited by Margret Shearer RECORDS’ CONTENT Description: Appraisal: Accruals: RECORDS’ CONDITION OF ACC. ESS AND USE Access: Open Closed until: - Access conditions: Available within the Archive searchroom Copying: Copying permitted within standard Copyright Act parameters Finding aids: Available in Archive searchroom ALLIED MATERIALS Related material: Publication: Notes: Nucleus: The Nuclear and Caithness Archive 1 Date of catalogue: 02 Feb 2018 Ref. Description Dates P898/1 Diaries 1975-2004 P898/1/1 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1975 P898/1/2 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1984 P898/1/3 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1987 P898/1/4 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1988 P898/1/5 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1989 P898/1/6 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1990 P898/1/7 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1991 P898/1/8 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1992 P898/1/9 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1993 P898/1/10 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1995 P898/1/11 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1996 P898/1/12 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1997 P898/1/13 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1998 P898/1/14 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 1999 P898/1/15 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 2000 P898/1/16 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 2001 P898/1/17 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 2002 P898/1/18/1 Harry Barrett’s personal diary [1 volume] 2003 P898/1/18/2 Envelope containing a newspaper clipping, receipts, 2003 addresses and a ticket to the Retired Police Officers Association, Scotland Highlands and Island Branch 100 Club (Inside P898/1/18/1). -

77 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

77 bus time schedule & line map 77 Gills View In Website Mode The 77 bus line (Gills) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Gills: 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM (2) John O' Groats: 1:05 PM (3) Wick: 9:12 AM - 6:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 77 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 77 bus arriving. Direction: Gills 77 bus Time Schedule 38 stops Gills Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM Town Hall, Wick Bridge Street, Wick Tuesday 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM Post O∆ce, Wick Wednesday 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM Oag Lane, Wick Thursday 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM Elm Tree Garage, Wick Friday 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM George Street, Wick Saturday 8:32 AM - 5:35 PM Hill Avenue, Wick North Road, Scotland Tesco, Wick 77 bus Info Tesco, Wick Direction: Gills Stops: 38 Business Park, Wick Trip Duration: 39 min Line Summary: Town Hall, Wick, Post O∆ce, Wick, Road End, Ackergill Elm Tree Garage, Wick, Hill Avenue, Wick, Tesco, Wick, Tesco, Wick, Business Park, Wick, Road End, Ackergill, Sands Road End, Reiss Sands Road End, Reiss, Crossroads, Reiss, Lower Reiss Road End, Reiss, Quoys Of Reiss, Reiss, Crossroads, Reiss Killimster Road End, Keiss, Lyth Road End, Keiss, Beach Road End, Keiss, Old Garage, Keiss, Hawkhill Lower Reiss Road End, Reiss Road End, Keiss, Road End, Nybster, Petrol Station, Auckengill, Park View Road End, Auckengill, Freswick Quoys Of Reiss, Reiss House Road End, Freswick, Skirza Road End, Freswick, Tofts House, Freswick, Canisbay Road End, Freswick, Hilltop House, John O' -

Highlands and Islands Enterprise

HIGHLANDS AND ISLANDS ENTERPRISE A FRAMEWORK FOR DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT AMBITIOUS FOR TOURISM CAITHNESS AND NORTH SUTHERLAND Full Report – Volume II (Research Document) (April 2011) TOURISM RESOURCES COMPANY Management Consultancy and Research Services In Association with EKOS 2 LA BELLE PLACE, GLASGOW G3 7LH Tel: 0141-353 1143 Fax: 0141-353 2560 Email: [email protected] www.tourism-resources.co.uk Management Consultancy and Research Services 2 LA BELLE PLACE, GLASGOW G3 7LH Tel: 0141-353 1143 Fax: 0141-353 2560 Email: [email protected] www.tourism-resources.co.uk Ms Rachel Skene Head of Tourism Caithness and North Sutherland Highlands and Islands Enterprise Tollemache House THURSO KW14 8AZ 18th April 2011 Dear Ms Skene AMBITIOUS FOR TOURISM CAITHNESS AND NORTH SUTHERLAND We have pleasure in presenting Volume II of our report into the opportunities for tourism in Caithness and North Sutherland. This report is in response to our proposals (Ref: P1557) submitted to you in October 2010. Regards Yours sincerely (For and on behalf of Tourism Resources Company) Sandy Steven Director Ref: AJS/IM/0828-FR1 Vol II Tourism Resources Company Ltd Reg. Office: 2 La Belle Place, Glasgow G3 7LH Registered in Scotland No. 132927 Highlands & Islands Enterprise Volume II Tourism Resources Company Ambitious for Tourism Caithness and North Sutherland April 2011 AMBITIOUS FOR TOURISM CAITHNESS AND NORTH SUTHERLAND – VOLUME II APPENDICES I Audit of Tourism Infrastructure Products / Services and Facilities by Type Electronic Database Supplied -

Ancient and Other Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

Orkney and Shetland

History, Heritage and Archaeology Orkney and Shetland search Treasures from St Ninian’s Isle, Shetland search St Magnus Cathedral, Orkney search Shetland fiddling traditions search The Old Man of Hoy, Orkney From the remains of our earliest settlements going back Ring of Brodgar which experts estimate may have taken more thousands of years, through the turbulent times of the than 80,000 man-hours to construct. Not to be missed is the Middle Ages and on to the Scottish Enlightenment and fascinating Skara Brae - a cluster of eight houses making up the Industrial Revolution, every area of Scotland has its Northern Europe’s best-preserved Neolithic village. own tale to share with visitors. You’ll also find evidence of more recent history to enjoy, such The Orkney islands have a magical quality and are rich in as Barony Mill, a 19th century mill which produced grain for history. Here, you can travel back in time 6,000 years and Orkney residents, and the Italian Chapel, a beautiful place of explore Neolithic Orkney. There are mysterious stone circles worship built by Italian prisoners of war during WWII. to explore such as the Standing Stones of Stenness, and the The Shetland Islands have a distinctive charm and rich history, and are littered with intriguing ancient sites. Jarlshof Prehistoric and Norse Settlement is one of the most Events important and inspirational archaeological sites in Scotland, january Up Helly Aa while 2,000 year old Mousa Broch is recognised as one of www.uphellyaa.org Europe’s archaeological marvels. The story of the internationally famous Shetland knitting, Orkney Folk Festival M ay with its intricate patterns, rich colours and distinctive yarn www.orkneyfolkfestival.com spun from the wool of the hardy breed of sheep reared on the islands, can be uncovered at the Shetland Textile Museum.