A Multi-Media Document of Scottish Settlements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pictish Symbol Stones and Early Cross-Slabs from Orkney

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 144 (2014), PICTISH169–204 SYMBOL STONES AND EARLY CROSS-SLABS FROM ORKNEY | 169 Pictish symbol stones and early cross-slabs from Orkney Ian G Scott* and Anna Ritchie† ABSTRACT Orkney shared in the flowering of interest in stone carving that took place throughout Scotland from the 7th century AD onwards. The corpus illustrated here includes seven accomplished Pictish symbol- bearing stones, four small stones incised with rough versions of symbols, at least one relief-ornamented Pictish cross-slab, thirteen cross-slabs (including recumbent slabs), two portable cross-slabs and two pieces of church furniture in the form of an altar frontal and a portable altar slab. The art-historical context for this stone carving shows close links both with Shetland to the north and Caithness to the south, as well as more distant links with Iona and with the Pictish mainland south of the Moray Firth. The context and function of the stones are discussed and a case is made for the existence of an early monastery on the island of Flotta. While much has been written about the Picts only superb building stone but also ideal stone for and early Christianity in Orkney, illustration of carving, and is easily accessible on the foreshore the carved stones has mostly taken the form of and by quarrying. It fractures naturally into flat photographs and there is a clear need for a corpus rectilinear slabs, which are relatively soft and can of drawings of the stones in related scales in easily be incised, pecked or carved in relief. -

Theses Digitisation: This Is a Digitised

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] VOLUME 3 ( d a t a ) ter A R t m m w m m d geq&haphy 2 1 SHETLAND BROCKS Thesis presented in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor 6f Philosophy in the Facility of Arts, University of Glasgow, 1979 ProQuest Number: 10984311 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10984311 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. -

Program of the 76Th Annual Meeting

PROGRAM OF THE 76 TH ANNUAL MEETING March 30−April 3, 2011 Sacramento, California THE ANNUAL MEETING of the Society for American Archaeology provides a forum for the dissemination of knowledge and discussion. The views expressed at the sessions are solely those of the speakers and the Society does not endorse, approve, or censor them. Descriptions of events and titles are those of the organizers, not the Society. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Published by the Society for American Archaeology 900 Second Street NE, Suite 12 Washington DC 20002-3560 USA Tel: +1 202/789-8200 Fax: +1 202/789-0284 Email: [email protected] WWW: http://www.saa.org Copyright © 2011 Society for American Archaeology. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher. Program of the 76th Annual Meeting 3 Contents 4................ Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting Agenda 5………..….2011 Award Recipients 11.................Maps of the Hyatt Regency Sacramento, Sheraton Grand Sacramento, and the Sacramento Convention Center 17 ................Meeting Organizers, SAA Board of Directors, & SAA Staff 18 ............... General Information . 20. .............. Featured Sessions 22 ............... Summary Schedule 26 ............... A Word about the Sessions 28…………. Student Events 29………..…Sessions At A Glance (NEW!) 37................ Program 169................SAA Awards, Scholarships, & Fellowships 176................ Presidents of SAA . 176................ Annual Meeting Sites 178................ Exhibit Map 179................Exhibitor Directory 190................SAA Committees and Task Forces 194…….…….Index of Participants 4 Program of the 76th Annual Meeting Awards Presentation & Annual Business Meeting APRIL 1, 2011 5 PM Call to Order Call for Approval of Minutes of the 2010 Annual Business Meeting Remarks President Margaret W. -

Modern Rune Carving in Northern Scotland. Futhark 8

Modern Rune Carving in Northern Scotland Andrea Freund and Ragnhild Ljosland (University of the Highlands and Islands) Abstract This article discusses modern runic inscriptions from Orkney and Caithness. It presents various examples, some of which were previously considered “genuine”, and reveals that OR 13 Skara Brae is of modern provenance. Other examples from the region can be found both on boulders or in bedrock and in particular on ancient monuments ranging in date from the Neolithic to the Iron Age. The terminology applied to modern rune carving, in particular the term “forgery”, is examined, and the phenomenon is considered in relation to the Ken sington runestone. Comparisons with modern rune carving in Sweden are made and suggestions are presented as to why there is such an abundance of recently carved inscriptions in Northern Scotland. Keywords: Scotland, Orkney, Caithness, modern runic inscriptions, modern rune carving, OR 13 Skara Brae, Kensington runestone Introduction his article concerns runic inscriptions from Orkney and Caithness Tthat were, either demonstrably or arguably, made in the modern period. The objective is twofold: firstly, the authors aim to present an inventory of modern inscriptions currently known to exist in Orkney and Caith ness. Secondly, they intend to discuss the concept of runic “forgery”. The question is when terms such as “fake” or “forgery” are helpful in de scribing a modern runic inscription, and when they are not. Included in the inventory are only those inscriptions which may, at least to an untrained eye, be mistaken for premodern. Runes occurring for example on jewellery, souvenirs, articles of clothing, in logos and the Freund, Andrea, and Ragnhild Ljosland. -

Heart of Neolithic Orkney Map and Guide

World heritage The remarkable monuments that make up the Heart of Neolithic Orkney were inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1999. These sites give visitors Heart of a vivid glimpse into the creative genius, lost beliefs and everyday lives of a once flourishing culture. Neolithic World Heritage status places them alongside such globally © Raymond Besant World heritage iconic sites as the Pyramids of Egypt and the Taj Mahal. Sites Orkney site r anger service are listed because they are of importance to all of humanity. The monuments World Heritage Site Orkney’s rich cultural and natural heritage is brought to life R anger Service Ring of Brodgar by the WHS Rangers and team of The evocative Ring of Brodgar is one of the largest and volunteers who support them. best-preserved stone circles in Great Britain. It hints at Throughout the year they run a busy programme of forgotten ritual and belief. public walks, talks and family events for all ages and Skara Brae levels of interest. The village of Skara Brae with its houses and stone Every day at 1pm in June, July and August the Rangers furniture presents an insight into the daily lives of lead walks around the Ring of Brodgar to explore the Neolithic people that is unmatched in northern Europe. iconic monument and its surrounding landscape. There Stones of Stenness are also activities designed specifically for schools and education groups. The Stones of Stenness are the remains of one of the oldest stone circles in the country, raised about 5,000 years ago. The Rangers work closely with the local community to care for the historical landscape and the wildlife that Maeshowe lives in and around its monuments. -

PS-Intros-Neo-10-Houses-Late

INTRODUCTION TO PREHISTORY NEOLITHIC FACTSHEET 10 LATE NEOLITHIC HOUSES Until fairly recently, Late Neolithic houses in immediately visible when one enters the building. Britain were extremely rare and almost Set into the floor may be other smaller features, unknown outside of the Northern Isles. The also defined by edge-set stones perhaps for best known settlement is Skara Brae on Orkney short term storage of foodstuffs or water. There and this has often been considered as the may also be quern or grinding stones for the archetypal ‘Neolithic Village’ though this preparation of grain and other foods. hypothesis is becoming increasingly challenged. Despite the similarity in architecture, some The Late Neolithic conventionally spans the buildings may have had different functions. At period from 3000 BC until the arrival of Beakers Barnhouse, for example, House 2 is a double at about 2400 BC. This is also the currency of a structure whilst House 8 is surrounded by its pan-British pottery type called Grooved Ware own enclosure wall. At Skara Brae, House 8 is with which the settlements are usually slightly more oval in internal plan and is set apart associated. This pottery appears to have had its from the rest of the settlement. At Ness of origins in Orkney but quickly spread over Britain Brodgar, the buildings are very much larger than and Ireland. the other sites, effectively halls with internal stone-built piers and the settlement is enclosed The site at Skara Brae was discovered around by what appears to have been a large defensive 1850 after a great storm had washed away part wall. -

The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 5 Print Reference: Pages 561-572 Article 43 2003 The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island Lawson L. Schroeder Philip L. Schroeder Bryan College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Schroeder, Lawson L. and Schroeder, Philip L. (2003) "The Significance of the Ancient Standing Stones, Villages, Tombs on Orkney Island," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 5 , Article 43. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol5/iss1/43 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE ANCIENT STANDING STONES, VILLAGES AND TOMBS FOUND ON THE ORKNEY ISLANDS LAWSON L. SCHROEDER, D.D.S. PHILIP L. SCHROEDER 5889 MILLSTONE RUN BRYAN COLLEGE STONE MOUNTAIN, GA 30087 P. O. BOX 7484 DAYTON, TN 37321-7000 KEYWORDS: Orkney Islands, ancient stone structures, Skara Brae, Maes Howe, broch, Ring of Brodgar, Standing Stones of Stenness, dispersion, Babel, famine, Ice Age ABSTRACT The Orkney Islands make up an archipelago north of Scotland. -

University of Bradford Ethesis

University of Bradford eThesis This thesis is hosted in Bradford Scholars – The University of Bradford Open Access repository. Visit the repository for full metadata or to contact the repository team © University of Bradford. This work is licenced for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence. THE NEOLITHIC AND LATE IRON AGE POTTERY FROM POOL, SANDAY, ORKNEY An archaeological and technological consideration of coarse pottery manufacture at the Neolithic and Late Iron Age site of Pool, Orkney, incorporating X-Ray Fluorescence, Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometric and Petrological Analyses 2 Volumes Volume 1 Ann MACSWEEN submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeological Sciences University of Bradford 1990 ABSTRACT Ann MacSween The Neolithic and Late Iron Age Pottery from Pool, Sanday, Orkney: An archaeological and technological consideration of coarse pottery manufacture at the Iron Age site of Pool, Orkney, incorporating X-Ray Fluorescence, Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometric and Petrological Analyses Key Words: Neolithic; Iron Age; Orkney; pottery; X-ray Fluorescence; Inductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometry; Petrological Analysis The Neolithic and late Iron Age pottery from the settlement site of Pool, Sanday, Orkney, was studied on two levels. Firstly, a morphological and tech- nological study was carried out to establish a se- quence for the site. Secondly an assessment was made of the usefulness of X-ray Fluorescence Analysis, In- ductively Coupled Plasma Spectrometry and Petrological analysis to coarse ware studies, using the Pool assem- blage as a case study. Recording of technological and typological attributes allowed three phases of Neolithic pottery to be iden- tified. The earliest phase included sherds of Unstan Ware. -

MODERN PROCESSES and PLEISTOCENE LEGACIES by Louise M. Farquharson, Msc. a Dissertation Submitted In

ARCTIC LANDSCAPE DYNAMICS: MODERN PROCESSES AND PLEISTOCENE LEGACIES By Louise M. Farquharson, MSc. A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geology University of Alaska Fairbanks December 2017 APPROVED: Daniel Mann, Committee Chair Vladimir Romanovsky, Committee Co-Chair Guido Grosse, Committee Member Benjamin M. Jones, Committee Member David Swanson, Committee Member Paul McCarthy, Chair Department of Geoscience Paul Layer, Dean College of Natural Science and Mathematics Michael Castellini, Dean of the Graduate School Abstract The Arctic Cryosphere (AC) is sensitive to rapid climate changes. The response of glaciers, sea ice, and permafrost-influenced landscapes to warming is complicated by polar amplification of global climate change which is caused by the presence of thresholds in the physics of energy exchange occurring around the freezing point of water. To better understand how the AC has and will respond to warming climate, we need to understand landscape processes that are operating and interacting across a wide range of spatial and temporal scales. This dissertation presents three studies from Arctic Alaska that use a combination of field surveys, sedimentology, geochronology and remote sensing to explore various AC responses to climate change in the distant and recent past. The following questions are addressed in this dissertation: 1) How does the AC respond to large scale fluctuations in climate on Pleistocene glacial-interglacial time scales? 2) How do legacy effects relating to Pleistocene landscape dynamics inform us about the vulnerability of modern land systems to current climate warming? and 3) How are coastal systems influenced by permafrost and buffered from wave energy by seasonal sea ice currently responding to ongoing climate change? Chapter 2 uses sedimentology and geochronology to document the extent and timing of ice-sheet glaciation in the Arctic Basin during the penultimate interglacial period. -

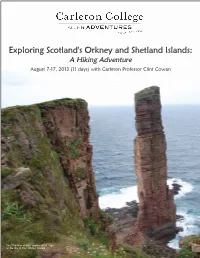

With Carleton Professor Clint Cowan

August 7-17, 2013 (11 days) with Carleton Professor Clint Cowan The "Old Man of Hoy" stands 450 ft. high on the Isle of Hoy, Orkney Islands. Dear Carleton College Alumni and Friends, I invite you to join Carleton College geologist Clint Cowan ’83 on this unique new hiking tour in Scotland’s little-visited Orkney and Shetland Islands! This is the perfect opportunity to explore on foot Scotland’s Northern Isles' amazing wealth of geological and archaeological sites. Their rocks tell the whole story, spanning almost three billion years. On Shet- land you will walk on an ancient ocean floor, explore an extinct volcano, and stroll across shifting sands. In contrast, Orkney is made up largely of sedimentary rocks, one of the best collections of these sediments to be seen anywhere in the world. Both archipelagoes also have an amazing wealth of archaeological sites dating back 5,000 years. This geological and archaeological saga is worth the telling, and nowhere else can the evidence be seen in more glorious a setting. Above & Bottom: The archaeological site of Jarlshof, dat- ing back to 2500 B.C. Below: A view of the Atlantic from This active land tour features daily hikes that are easy to moderate the northern Shetland island of Unst. in difficulty, so to fully enjoy and visit all the sites on this itinerary one should be in good walking condition (and, obviously, enjoy hiking!). Highlights include: • The “Heart of Neolithic Orkney,” inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1999, including the chambered tomb of Maeshowe, estimated to have been constructed around 2700 B.C.; the 4,000 year old Ring of Brodgar, one of Europe’s finest Neolithic monu- ments; Skara Brae settlement; and associated monuments and stone settings. -

Orkney - the Cultural Hub of Britain in 3,500 Bc - a World Heritage Site from 1999

ORKNEY - THE CULTURAL HUB OF BRITAIN IN 3,500 BC - A WORLD HERITAGE SITE FROM 1999. THE INGENIOUS PRE-HISTORIC INHABITANTS OF WHAT ONLY BECAME SCOTLAND IN THE 9TH CENTURY AD. By James Macnaughton As indicated in the title, people lived in the Northern part of Britain for many thousands of years before it became Scotland and they were called Scots. Given its wet, cool climate and its very mountainous terrain, those inhabitants were always living on the edge, fighting to grow enough food to survive through the long winters and looking for ways to breed suitable livestock to provide both food and skins and furs from which they could fashion clothing to keep them warm and dry. 20,000 years ago, present day Scotland lay under a 1.5 Km deep ice-sheet.This is so long ago that it is difficult to imagine, but if you consider a generation to be 25 years, then this was 800 generations ago, and for us to think beyond even two or three generations of our families, this is almost unimaginable. From 11,000 years, ago, the ice was gradually melting from the South of England towards the North and this occurred more quickly along the coasts where the ice was not so thick. Early inhabitants moved North along the sea coasts as hunter gatherers and by 10,000 years ago, some of them had settled near Banchory in Aberdeenshire on the banks of the River Dee. The warming climate and the plentiful supply of fish from the river, and game from the surrounding forests, encouraged them to create a permanent settlement and to change from nomadic hunter gatherers to settled farmers. -

Land, Stone, Trees, Identity, Ambition

Edinburgh Research Explorer Land, stone, trees, identity, ambition Citation for published version: Romankiewicz, T 2015, 'Land, stone, trees, identity, ambition: The building blocks of brochs', The Archaeological Journal, vol. 173 , no. 1, pp. 1-29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00665983.2016.1110771 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1080/00665983.2016.1110771 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: The Archaeological Journal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Land, Stone, Trees, Identity, Ambition: the Building Blocks of Brochs Tanja Romankiewicz Brochs are impressive stone roundhouses unique to Iron Age Scotland. This paper introduces a new perspective developed from architectural analysis and drawing on new survey, fieldwork and analogies from anthropology and social history. Study of architectural design and constructional detail exposes fewer competitive elements than previously anticipated. Instead, attempts to emulate, share and communicate identities can be detected. The architectural language of the broch allows complex layers of individual preferences, local and regional traditions, and supra-regional communications to be expressed in a single house design.