Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Paintings by Frederic Edwin Church

Bibliography for The American Landscape's "Quieter Spirit": Early Paintings by Frederic Edwin Church Books and a bibliography of additional sources are available in the Reading Room of the Dorothy Stimson Bullitt Library (SAM, Downtown). Avery, Kevin J. and Kelly, Franklin. Hudson River School visions: the landscapes of Sanford R. Gifford (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003). Carr, Gerald L. and Harvey, Eleanor Jones. The voyage of the icebergs: Frederic Church's arctic masterpiece (Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002). _____. Frederic Edwin Church: the icebergs (Dallas: Dallas Museum of Fine Arts, 1980). _____. In search of the promised land: paintings by Frederic Edwin Church (New York: Berry-Hill Galleries, Inc., 2000). Cock, Elizabeth. The influence of photography on American landscape painting 1839- 1880 (Ann Arbor: UMI Dissertation Services [dissertation], 1967). Driscoll, John Paul et al. John Frederick Kensett: an American master (New York: Worcester Art Museum, 1985). Fels, Thomas Weston. Fire & ice : treasures from the photographic collection of Frederic Church at Olana (New York: Dahesh Museum of Art; Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2002). Glauber, Carole. Witch of Kodakery: the photography of Myra Albert Wiggins, 1869- 1956 (Pullman: Washington State University Press, 1997). Harmon, Kitty. The Pacific Northwest landscape: a painted history (Seattle: Sasquatch Books, 2001). Hendricks, Gordon. Albert Bierstadt: painter of the American West (New York: H. N. Abrams, 1974). Howat, John K. The Hudson River and its painters (New York: Viking Press, 1972). Huntington, David C. The landscapes of Frederic Edwin Church: vision of an American era (New York: G. -

Sir John Franklin and the Arctic

SIR JOHN FRANKLIN AND THE ARCTIC REGIONS: SHOWING THE PROGRESS OF BRITISH ENTERPRISE FOR THE DISCOVERY OF THE NORTH WEST PASSAGE DURING THE NINE~EENTH CENTURY: WITH MORE DETAILED NOTICES OF THE RECENT EXPEDITIONS IN SEARCH OF THE MISSING VESSELS UNDER CAPT. SIR JOHN FRANKLIN WINTER QUARTERS IN THE A.ROTIO REGIONS. SIR JOHN FRANKLIN AND THE ARCTIC REGIONS: SHOWING FOR THE DISCOVERY OF THE NORTH-WEST PASSAGE DURING THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: WITH MORE DETAILED NOTICES OF THE RECENT EXPEDITIONS IN SEARCH OF THE MISSING VESSELS UNDER CAPT. SIR JOHN FRANKLIN. BY P. L. SIMMONDS, HONORARY AND CORRESPONDING JIIEl\lBER OF THE LITERARY AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF QUEBEC, NEW YORK, LOUISIANA, ETC, AND MANY YEARS EDITOR OF THE COLONIAL MAGAZINE, ETC, ETC, " :Miserable they Who here entangled in the gathering ice, Take their last look of the descending sun While full of death and fierce with tenfold frost, The long long night, incumbent o•er their heads, Falls horrible." Cowl'ER, LONDON: GEORGE ROUTLEDGE & CO., SOHO SQUARE. MDCCCLI. TO CAPT. SIR W. E. PARRY, R.N., LL.D., F.R.S., &c. CAPT. SIR JAMES C. ROSS, R.N., D.C.L., F.R.S. CAPT. SIR GEORGE BACK, R.N., F.R.S. DR. SIR J. RICHARDSON, R.N., C.B., F.R.S. AND THE OTHER BRAVE ARCTIC NAVIGATORS AND TRAVELLERS WHOSE ARDUOUS EXPLORING SERVICES ARE HEREIN RECORDED, T H I S V O L U M E I S, IN ADMIRATION OF THEIR GALLANTRY, HF.ROIC ENDURANCE, A.ND PERSEVERANCE OVER OBSTACLES OF NO ORDINARY CHARACTER, RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED, BY THEIR VERY OBEDIENT HUMBLE SERVANT, THE AUTHOR. -

NEA-Annual-Report-1992.Pdf

N A N A L E ENT S NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR~THE ARTS 1992, ANNUAL REPORT NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR!y’THE ARTS The Federal agency that supports the Dear Mr. President: visual, literary and pe~orming arts to I have the honor to submit to you the Annual Report benefit all A mericans of the National Endowment for the Arts for the fiscal year ended September 30, 1992. Respectfully, Arts in Education Challenge &Advancement Dance Aria M. Steele Design Arts Acting Senior Deputy Chairman Expansion Arts Folk Arts International Literature The President Local Arts Agencies The White House Media Arts Washington, D.C. Museum Music April 1993 Opera-Musical Theater Presenting & Commissioning State & Regional Theater Visual Arts The Nancy Hanks Center 1100 Pennsylvania Ave. NW Washington. DC 20506 202/682-5400 6 The Arts Endowment in Brief The National Council on the Arts PROGRAMS 14 Dance 32 Design Arts 44 Expansion Arts 68 Folk Arts 82 Literature 96 Media Arts II2. Museum I46 Music I94 Opera-Musical Theater ZlO Presenting & Commissioning Theater zSZ Visual Arts ~en~ PUBLIC PARTNERSHIP z96 Arts in Education 308 Local Arts Agencies State & Regional 3z4 Underserved Communities Set-Aside POLICY, PLANNING, RESEARCH & BUDGET 338 International 346 Arts Administration Fallows 348 Research 35o Special Constituencies OVERVIEW PANELS AND FINANCIAL SUMMARIES 354 1992 Overview Panels 360 Financial Summary 36I Histos~f Authorizations and 366~redi~ At the "Parabolic Bench" outside a South Bronx school, a child discovers aspects of sound -- for instance, that it can be stopped with the wave of a hand. Sonic architects Bill & Mary Buchen designed this "Sound Playground" with help from the Design Arts Program in the form of one of the 4,141 grants that the Arts Endowment awarded in FY 1992. -

Preface in Full Review Before the Eye: Visuality and the Arctic Regions

Preface In Full Review Before The Eye: Visuality and the Arctic Regions The fascination of Western culture with the Arctic regions is of ancient origin, and shows little sign of abating today, more than two millennia after Pytheas of Massalia sailed to a land he named Thule, the ultimate end of the earth. Yet throughout its long duration, this persistent attraction has been shaped by the fact that the Arctic is a place that very few people will ever see for themselves. The far North has remained, despite its ostensible “discovery,” a largely unseen country, more vividly alive and alluring in its absence from actual sight than it ever would have been if, like other regions of the “New” world, it had been colonized and developed in the early centuries of European expansion. For this reason, the stakes in the visual depiction of the Arctic have always been different than those for nearly any other place on earth, spurring the imagination new heights, even after these depictions began to be based on the actual observations of explorers. Imagined yet unseen, the Arctic functioned for the nineteenth century much as the Moon and outer space did for the twentieth: a place where, against a backdrop of nameless coastlines and unfamiliar seas, the human drama was enacted in its most condensed and absolute form. There explorers, aided only by their wits and science, traveled in capsules of civilization, in which were condensed a miniature array of the distant comforts of home. And, just as photographs and televised images of the astronauts wandering -

Field Report

northwest passage September 4 - 23, 2015 GREENLAND ARCTIC OCEAN Qaanaaq Kullorsuaq Upernavik Uummannaq EQIP SERMIA GLACIER BEECHEY Ilulissat ISLAND DEVON ISLAND BAFFIN BAY Sisimiut SOMERSET ISLAND Fury Beach BAFFIN Kangerlussuaq ISLAND BELLOT STRAIT Fort Cape Felix Ross Kugluktuk KING WILLIAM ISLAND QUEEN MAUDE GULF BATHURST JENNY LIND INLET ISLAND CANADA Saturday, September 5, 2015 Edmonton, Canada / Kugluktuk, Nunavut / Embark Sea Adventurer Full of excited chatter, we boarded our charter flight this morning as we left Edmonton for Kugluktuk. A brief refueling stop en route at Yellowknife gave us a nice view of Great Slave Lake and the last obvious trees we would see for the rest of the trip. Soon we landed on the small airstrip amidst the low tundra landscapes of Kugluktuk and set off along the dusty roads to the community hall, where we were treated to refreshments and a display of local dances and songs. Next door was the impressive new Ulu Centre, shaped like one of the traditional Inuit knives, which contained wonderful exhibits of local life and culture. Awaiting us out in the bay was the Sea Adventurer, and a short Zodiac ride took us to our home for the next few weeks. Our Northwest Passage adventure was underway! Sunday, September 6 Bathurst Inlet A beautiful sunrise lit up the south coast of Victoria Island as we sailed east through Coronation Gulf. After breakfast, our Expedition Leader, Mike Messick, introduced the members of our expedition team before an entertaining but essential briefing on polar bear safety from naturalist, Conrad Field. Later, maritime historian, Jim Delgado, presented the Quest for the Northwest Passage and the tragic tale of Sir John Franklin, whose name is forever associated with the exploration of the Canadian Arctic. -

Featured Releases 2 Limited Editions 102 Journals 109

Lorenzo Vitturi, from Money Must Be Made, published by SPBH Editions. See page 125. Featured Releases 2 Limited Editions 102 Journals 109 CATALOG EDITOR Thomas Evans Fall Highlights 110 DESIGNER Photography 112 Martha Ormiston Art 134 IMAGE PRODUCTION Hayden Anderson Architecture 166 COPY WRITING Design 176 Janine DeFeo, Thomas Evans, Megan Ashley DiNoia PRINTING Sonic Media Solutions, Inc. Specialty Books 180 Art 182 FRONT COVER IMAGE Group Exhibitions 196 Fritz Lang, Woman in the Moon (film still), 1929. From The Moon, Photography 200 published by Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. See Page 5. BACK COVER IMAGE From Voyagers, published by The Ice Plant. See page 26. Backlist Highlights 206 Index 215 Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future Edited with text by Tracey Bashkoff. Text by Tessel M. Bauduin, Daniel Birnbaum, Briony Fer, Vivien Greene, David Max Horowitz, Andrea Kollnitz, Helen Molesworth, Julia Voss. When Swedish artist Hilma af Klint died in 1944 at the age of 81, she left behind more than 1,000 paintings and works on paper that she had kept largely private during her lifetime. Believing the world was not yet ready for her art, she stipulated that it should remain unseen for another 20 years. But only in recent decades has the public had a chance to reckon with af Klint’s radically abstract painting practice—one which predates the work of Vasily Kandinsky and other artists widely considered trailblazers of modernist abstraction. Her boldly colorful works, many of them large-scale, reflect an ambitious, spiritually informed attempt to chart an invisible, totalizing world order through a synthesis of natural and geometric forms, textual elements and esoteric symbolism. -

Video History Project

VIDEO HISTORY PROJECT We have been working on the VIDEO HISTORY PROJECT for about five years. It has a varied pedigree - Ralph's long love of old machines; 30 years of work at the Center; teaching A Natural History of Video at Visual Studies Workshop's Summer Institute; concern for reclaiming the history of our medium; an appreciation ofthe transitory nature of human beings and the fragility of the materials which they use to record their thoughts and feelings; a desire to preserve these traces - both tape and apparatus; a love of tools and images; the enthusiasm of friends and co-workers willing to become engaged in this endless work. It is a project with several faces. It is about research, and the collecting and organizing of information which locates and documents media history resources - tapes, artists' instruments, writings and ephemera. It is about sharing information and reaching out to new audiences, about increasing awareness of how and where to find the artworks, and helping to create contexts in which the work can be more widely presented and appreciated . It is about strengthening preservation efforts to rescue deteriorating tape-based works, so there will always be something to see. It is about coming together to celebrate our field, to learn from each other, to discover parallels and intersections between early activities and contemporary practice. To continue the conversations. The conference, VIDEO HISTORY: MAKING CONNECTIONS, is a way to celebrate our history, and to renew a commitment to saving the stories, memories and works which have come out of the last 30 years of experimentation . -

A Chronology of Video Activity in the United States: 1965–1980 - Artforum International

10/11/2019 A Chronology of Video Activity in the United States: 1965–1980 - Artforum International TABLE OF CONTENTS PRINT SEPTEMBER 1980 A CHRONOLOGY OF VIDEO ACTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES: 1965–1980 This chronology in now way covers all video exhibitions or artists’ video activities in the United States. Instead it concentrates on events and works that have deeply influenced the development of video history. Guaranteed sources for a medium which is only in the process of documenting itself are not always available. Much source material is extremely ephemeral and often contradictory, and many of the enterprises mentioned here are no longer in existence. 1965 Sony introduced the first portable 1/2-inch black-and-white videotape camera and recorder in U.S. (limited availability). https://www.artforum.com/print/198007/a-chronology-of-video-activity-in-the-united-states-1965-1980-37724 1/28 10/11/2019 A Chronology of Video Activity in the United States: 1965–1980 - Artforum International “Third Annual New York Avant-Garde Festival.” Judson Hall, New York City. Included video sculpture by Nam June Paik. Café au Go Go, New York City. First use of Sony Portapak by video artist in U.S. “Electronic Art,” Nam June Paik, Bonino Gallery, New York City, Paik’s first American gallery exhibition. “New Cinema Festival I,” Filmmakers Cinemathèque, New York City. Included videotapes by Nam June Paik, with Charlotte Moorman, John Brockman, organizer. 1967 Sony 1/2-inch black and white portable videotape recorder and Portapak camera marketed for commercial sale in U.S. Electronic Blues, Nam June Paik. -

Notes for Teachers American Sublime Landscape Painting in the United States, 1820–1880 21 February – 19 May 2002 Supported by Glaxosmithkline

Notes for Teachers American Sublime Landscape painting in the United States, 1820–1880 21 February – 19 May 2002 Supported by GlaxoSmithKline Foundation Sponsor The Henry Luce Foundation Thomas Moran, Hiawatha and the Great Serpent, the Kenabeek, 1867 By kind courtesy of The Baltimore Museum of Art: Friends of Art Fund By Roger Hull, Professor of Art History, Willamette University, Salem, Oregon NORTH EASTERN UNITED STATES WESTERN UNITED STATES 1. Introduction American Sublime is an exhibition of paintings by ten nineteenth-century artists, well known to American art audiences but mostly unseen in England since the reign of Queen Victoria. Some of the artists were born in England where landscape painting had reached its zenith in the first half of the nineteenth century with the Romantic generation led by JMW Turner and John Constable. Helped by their awareness of eighteenth-century British theories of the Picturesque and Sublime, they evolved an indigenous landscape idiom in response to the astonishing scale and features of nature in the New World as well as to the national needs and aspirations of Americans in the century following their independence from Britain. This pack is mainly intended for secondary teachers to use with their students but year 5 and 6 children working on A Sense of Place would enjoy the drama of the paintings and teachers could adapt some of the ideas that follow for their use, for example by encouraging them to make an imaginary walk into the landscape. Some of the questions in the framed sections could be adapted for younger students. A trail is also available on request. -

Download Download

Seeing Icebergs and Inuit as Elemental Nature: An American Transcendentalist on and off the Coast of Labrador, 1864 J. I. LITTLE* In 1865 a series of Atlantic Monthly articles written by the Transcendentalist minister David Atwood Wasson described the voyage to Labrador organized by American landscape painter William Bradford. Bradford was inspired by the success of fellow Hudson River school artist Frederic Edwin Church’s monumental painting, The Icebergs (1861), and Wasson’s role was to generate publicity for what would be Bradford’s own “great picture,” Sealers Crushed by Icebergs. Wasson produced many colourful descriptions of the icebergs encountered on the voyage, but he also depicted the Labrador shorescape as the planet earth at the dawn of time and the Inuit of Hopedale as unevolved, pre-adamic man. This article suggests that Wasson’s racism and rejection of the benign, mystical Nature of first-generation Transcendentalists Thoreau and Emerson reflects the rise of evolutionary theory and the cultural impact of the American Civil War. En 1865, l’Atlantic Monthly décrivait, dans une série d’articles parus sous la plume du ministre transcendentaliste David Atwood Wasson, le voyage au Labrador organisé par William Bradford, un peintre de paysages américain. Ce dernier était inspiré par le succès de The Icebergs (1861), peinture monumentale d’un confrère de l’école de l’Hudson, l’artiste Frederic Edwin Church, et Wasson avait pour rôle de susciter de la publicité autour de ce qui allait être la propre « grande œuvre picturale » de Bradford, Sealers Crushed by Icebergs. Wasson a produit de nombreuses descriptions pittoresques des icebergs rencontrés en cours de route, mais il a aussi dépeint le paysage côtier du Labrador comme s’il s’agissait de la Terre au début des temps et l’Inuit de Hopedale comme s’il était une race non évolué, antérieur à Adam. -

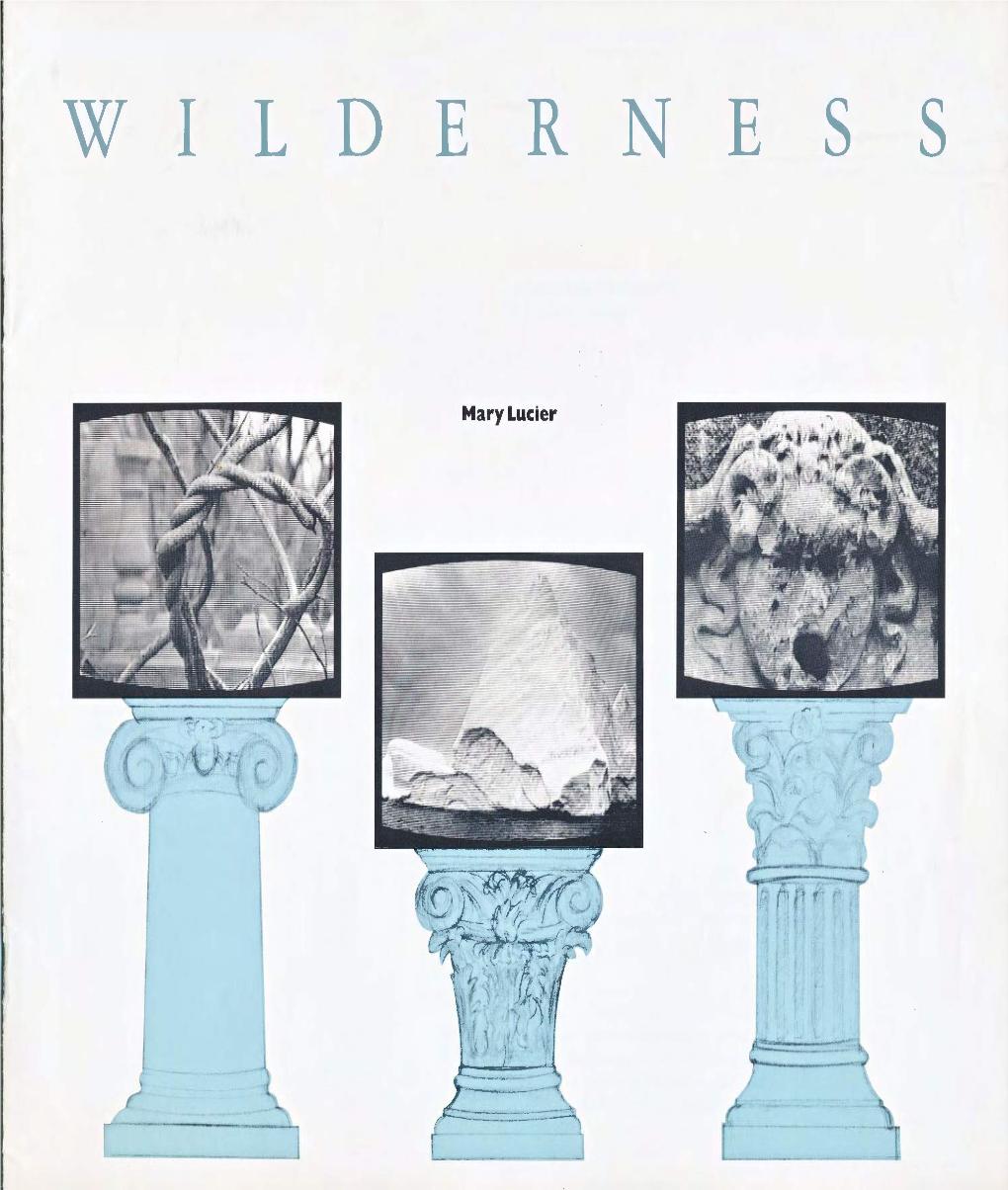

SET in MOTION : the New York State Council an the Arts

The New York State Council an the Arts Celebrates 30 Years of independentsSe FOR THE NEW YORK STATE COUNCIL ON THE ARTS PROJECT DIRECTOR Debby Silverfine Director, Electronic Media and Film Program CURATORS Linda Earle Director, Inddual Artists Program Independentcurator Leanne Mella FOR THE FILM SOCIETY OF LINCOLN CENTER Debby Silverfine Marian Masone Associate Programmer PROJECT ADMINISTRATOR Tony lmpavido Director of GalleryExhibitions Michele Rosenshein Joanna Ney DirectorofPoblicRelations CATALOGUE EDITOR Lucinda Furlong FOR THE AMERICAN FEDERATION OF ARTS CATALOGUE DESIGNER Sam McElfresh C,rator of Media Arts Exhibitions BarbaraGlauber HeavyMeta PRINTING Virginia Lithograph CATALOGUE RESEARCH Paula Jarowski PUBLICIST Gary Schiro Kahn and Jacobs, Inc. FISCAL CONDUIT PHOTOGRAPH CREDITS Upstate Films, Rhinebeck, N .Y . All film and video stills provided by the artist or SET IN MOTION OPENING SEQUENCE Steve Leiber and DeDe Lelber Co-Directors distributor, except where noted. The following Maureen Nappi video list applies to photographs where additional credit is Stephen Vitiello aodio due: p. 10, Meyer Braiterman ; p. 16, left, Katrina Images realized at Post Perfect, NYC Thomas; p. 18, left, Sedat Pakay, right, Marita Sturken; Audio mix at Harmonic Ranch, NYC p. 21, Marie Stein, p. 24, Paula Court; p. 27, courtesy Schomberg Center for Research on Black Culture; p. 33, top, Pamela Dopes Felderman, middle, Hella Hammid/Rapho-Guillumette ; p. 34, right, Gwen Sloan, far right, Lloyd Eby; p. 37, Kira Perov; p. 39, Emil Ghinger, p. 41 , courtesy Douglas Davis Studio ; p.43, courtesy Skip Blumberg ; p. 50, top, Rogers Murphy, bottom, Kristin Reed ; p. 51, bottom, Stephanie Foxx ; p. 52, bottom, Marita Sturken; p. -

Vanishing Ice Catalogue

Vanishing ICE ALPINE AND POLAR LANDSCAPES IN ART, 1775-2012 Vanishing ICE Vanishing ICE ALPINE AND POLAR LANDSCAPES IN ART, 1775-2012 BARBARa c. maTILSKY Francois-Auguste Biard, Pêche au morse par des Groënlandais, vue de l’Océan Glacial (Greenlanders hunting walrus, view of the Polar Sea), Salon of 1841. WHATcom museum, bellingham, wASHINGTON This publication accompanies the touring exhibition, Vanishing Ice: Alpine and Polar Landscapes in Art, 1775-2012, organized by Barbara C. Matilsky, for the Whatcom Museum. Major funding for the exhibition and catalogue has been provided by The Paul G. Allen Family Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, with additional support from The Norcliffe Foundation, the City of Bellingham, and the Washington State Arts Commission. Additional funding for the catalogue has been provided by Furthermore: a program of the J.M. Kaplan Fund. CONTENTS Whatcom Museum Bellingham, Washington November 2, 2013–March 2, 2014 DIRECTOR’s fOREWORD El Paso Museum of Art 7 El Paso, Texas June 1–August 24, 2014 PROLOGUE McMichael Canadian Art Collection Kleinberg, Ontario 9 October 11, 2014 –January 11, 2015 ©2013 by the Whatcom Museum. Text ©Barbara C. Matilsky. The copyright of works of art reproduced in this book are From the Sublime to the Science of a Changing CLIMAte retained by the artists, their heirs, successors, and assignees. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic 13 or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.