Teaching About Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRApHY PRIMARY SOURCEs Conversations and Correspondence with Lady Mary Whitley, Countess Mountbatten, Maitre Blum and Dr. Heald Judgements and Case Reports Newell, Ann: The Secret Life of Ellen, Lady Kilmorey, unpublished dissertation, 2016 Royal Archives, Windsor The Kilmorey Papers: Public Record Office of Northern Ireland The Teck Papers: Wellington College SECONDARY SOURCEs Aberdeen, Isobel. 1909. Marchioness of, Notes & Recollections. London: Constable. Annual Register Astle, Thomas. 1775. The Will of Henry VII. ECCO Print editions. Bagehot, Walter. 1867 (1872). The English Constitution. Thomas Nelson & Sons. Baldwin-Smith, Lacey. 1971. Henry VIII: The Mask of Royalty. London: Jonathan Cape. Benn, Anthony Wedgwood. 1993. Common Sense: A New Constitution for Britain, (with Andrew Hood). Brooke, the Hon. Sylvia Brooke. 1970. Queen of the Headhunters. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. Chamberlin, Frederick. 1925. The Wit & Wisdom of Good Queen Bess. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head. © The Author(s) 2017 189 M.L. Nash, Royal Wills in Britain from 1509 to 2008, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-60145-2 190 BIBLIOGRAPHY Chevenix-Trench, Charles. 1964. The Royal Malady. New York: Harcourt, Bruce & World Cronin, Vincent. 1964 (1990). Louis XIV. London: Collins Harvel. Davey, Richard. 1909. The Nine Days’ Queen. London: Methuen & Co. ———. 1912. The Sisters of Lady Jane Grey. New York: E.R. Dutton. De Lisle, Leanda. 2004. After Elizabeth: The Death of Elizabeth, and the Coming of King James. London: Harper Collins. Doran, John. 1875. Lives of the Queens of England of the House of Hanover, vols I & II. London: Richard Bentley & Sons. Edwards, Averyl. 1947. Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales. London/New York/ Toronto: Staples Press. -

Sir Walter Scott's Templar Construct

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. SIR WALTER SCOTT’S TEMPLAR CONSTRUCT – A STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY INFLUENCES ON HISTORICAL PERCEPTIONS. A THESIS PRESENTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY AT MASSEY UNIVERSITY, EXTRAMURAL, NEW ZEALAND. JANE HELEN WOODGER 2017 1 ABSTRACT Sir Walter Scott was a writer of historical fiction, but how accurate are his portrayals? The novels Ivanhoe and Talisman both feature Templars as the antagonists. Scott’s works display he had a fundamental knowledge of the Order and their fall. However, the novels are fiction, and the accuracy of some of the author’s depictions are questionable. As a result, the novels are more representative of events and thinking of the early nineteenth century than any other period. The main theme in both novels is the importance of unity and illustrating the destructive nature of any division. The protagonists unify under the banner of King Richard and the Templars pursue a course of independence. Scott’s works also helped to formulate notions of Scottish identity, Freemasonry (and their alleged forbearers the Templars) and Victorian behaviours. However, Scott’s image is only one of a long history of Templars featuring in literature over the centuries. Like Scott, the previous renditions of the Templars are more illustrations of the contemporary than historical accounts. One matter for unease in the early 1800s was religion and Catholic Emancipation. -

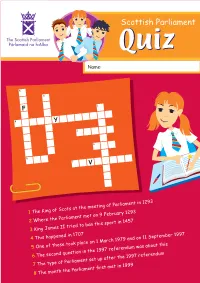

1 the King of Scots at the Meeting of Parliament in 1293 2 Where The

Name: F Y V 1 The King of Scots at the meeting of Parliament in 1293 2 Where the Parliament met on 9 February 1293 3 King James II tried to ban this sport in 1457 4 This happened in 1707 5 One of these took place on 1 March 1979 and on 11 September 1997 6 The second question in the 1997 referendum was about this 7 The type of Parliament set up after the 1997 referendum 8 The month the Parliament first met in 1999 What the Scottish Parliament can do The Scottish Parliament makes decisions that affect matters. our everyday lives and can______________________ pass laws on different things. These are called Some of these matters are: . The Scottish Parliament cannot make laws_________________ on reserved matters. These are dealt with by the Some examples of reserved matters are: The Honours of Scotland The ‘Honours of Scotland’ sculpture was created by silversmith ________________________________. The sculpture was presented to the Scottish Parliament by HM the ______________ to mark the opening of the Scottish Parliament building on Saturday 9 October 200_. The new sculpture is a reminder of the original three Honours of Scotland or the Crown Jewels – the Crown, the Sword and the Sceptre. Label the picture to show the three parts of the ‘Honours’. 1 1 ______________________________________ 2 2 ______________________________________ 3 ______________________________________ 3 What the Scottish Parliament can do The Scottish Parliament makes decisions that affect Passing laws in the Scottish Parliament matters. our everyday lives and can______________________ pass laws on different things. These are called New laws start as a proposal called a B_ _ _ . -

The Highland Clans of Scotland

:00 CD CO THE HIGHLAND CLANS OF SCOTLAND ARMORIAL BEARINGS OF THE CHIEFS The Highland CLANS of Scotland: Their History and "Traditions. By George yre-Todd With an Introduction by A. M. MACKINTOSH WITH ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS, INCLUDING REPRODUCTIONS Of WIAN'S CELEBRATED PAINTINGS OF THE COSTUMES OF THE CLANS VOLUME TWO A D. APPLETON AND COMPANY NEW YORK MCMXXIII Oft o PKINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PAGE THE MACDONALDS OF KEPPOCH 26l THE MACDONALDS OF GLENGARRY 268 CLAN MACDOUGAL 278 CLAN MACDUFP . 284 CLAN MACGILLIVRAY . 290 CLAN MACINNES . 297 CLAN MACINTYRB . 299 CLAN MACIVER . 302 CLAN MACKAY . t 306 CLAN MACKENZIE . 314 CLAN MACKINNON 328 CLAN MACKINTOSH 334 CLAN MACLACHLAN 347 CLAN MACLAURIN 353 CLAN MACLEAN . 359 CLAN MACLENNAN 365 CLAN MACLEOD . 368 CLAN MACMILLAN 378 CLAN MACNAB . * 382 CLAN MACNAUGHTON . 389 CLAN MACNICOL 394 CLAN MACNIEL . 398 CLAN MACPHEE OR DUFFIE 403 CLAN MACPHERSON 406 CLAN MACQUARIE 415 CLAN MACRAE 420 vi CONTENTS PAGE CLAN MATHESON ....... 427 CLAN MENZIES ........ 432 CLAN MUNRO . 438 CLAN MURRAY ........ 445 CLAN OGILVY ........ 454 CLAN ROSE . 460 CLAN ROSS ........ 467 CLAN SHAW . -473 CLAN SINCLAIR ........ 479 CLAN SKENE ........ 488 CLAN STEWART ........ 492 CLAN SUTHERLAND ....... 499 CLAN URQUHART . .508 INDEX ......... 513 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Armorial Bearings .... Frontispiece MacDonald of Keppoch . Facing page viii Cairn on Culloden Moor 264 MacDonell of Glengarry 268 The Well of the Heads 272 Invergarry Castle .... 274 MacDougall ..... 278 Duustaffnage Castle . 280 The Mouth of Loch Etive . 282 MacDuff ..... 284 MacGillivray ..... 290 Well of the Dead, Culloden Moor . 294 Maclnnes ..... 296 Maclntyre . 298 Old Clansmen's Houses 300 Maclver .... -

Scotland Scotland DEPART DATE: 04/10/2022 RETURN DATE: 04/18/2022 NUMBER of DAYS: 9

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– TRIP DETAILS –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– TEAM NAME: EPYSA Boys 2009 & 2010 DESTINATION: Scotland Scotland DEPART DATE: 04/10/2022 RETURN DATE: 04/18/2022 NUMBER OF DAYS: 9 YOUR DAY-BY-DAY ADVENTURE DAY 1 DAY 5 Flight to Scotland Breakfast at Hotel Please note: the final itinerary may be slightly Training Session different from this program. The final itinerary will be Scottish Football Museum Witness the thousands of determined based on the size of the group, any objects on display, tracing the history of football in adjustments that are required (such as adding Scotland and highlights some of the most memorable additional matches), and the final schedule of the games and players. Sit in what was the original matches. (If additional matches are required, then dressing room from the old Hampden and listen to some sightseeing content will be replaced by the Craig Brown addressing -

Investigating

Investigating Edinburgh Castle In many ways Edinburgh Castle has everything: a huge, forbidding presence, magnificent royal rooms, the priceless Honours of Scotland and Stone of Destiny, large numbers of weapons and grim prisons. The castle is unparalleled for the potential to explore in a single building the defensive role of castles, a medieval royal residence, a prison of war and a major tourist attraction. Edinburgh Castle sites 2 Edinburgh Castle In this resource you will find: Contents Edinburgh Castle: • suggestions for how a visit to p2 Edinburgh Castle can provide Edinburgh Castle: an an overview support for the 5–14 National overview Edinburgh Castle is one of over 300 Guidelines How to use this resource historically significant properties • ideas for integrating a visit with p3 throughout Scotland that are looked classroom learning through pre- and Supporting learning and after by Historic Scotland. It is post- visit activities teaching situated on an extinct volcanic outcrop • a map of Edinburgh Castle with that has provided a natural defensive background information and detailed p4 site for settlements and forts since the guidance notes for three teacher-led Integrating a visit with Bronze Age. By the 11th century, themed tours: classroom studies kings used the castle as a fortress Tour 1: Attackers and Defenders p5 and the oldest surviving castle Suggestions for follow- building, St Margaret’s Chapel, dates Tour 2: A Royal Household up work from this period. Tour 3: Prisons and Prisoners p6 There have been many changes since Timeline: Edinburgh then and much of the castle we see today How to book a visit Castle was built by James IV (1488–1513), Historic Scotland operates a free including the Great Hall and the Royal admission scheme for education p7 Apartments. -

Symbolism and Ritual in the 17Th Century Scottish Parliament

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository Symbolism and ritual in the seventeenth-century Scottish Parliament Alastair J. Mann (University of Stirling) Parliaments communicate with the people of their nations through a range of symbolic and ritualistic registers. The nature of symbolism and ceremony in the Scottish Parliament before the 1707 union with the parliament of England provides an interesting illustration of this communicative aspect.1 In particular seventeenth-century Scotland - an astonishingly traumatised place of political and religious strife – was home to a surprising reliance on rituals in spite of the atmosphere of conflict. In the last full century of this parliament’s long life, the impact of decades of revolution, warfare and economic collapse was even greater for Scotland than for England. Traditionally, in Scottish and English historiography, the woes of Scotland after 1603 are placed at the foot of government by absentee monarchy. Indeed although some seventeenth-century English contemporaries and modern English historians have reflected on the negative consequences of a Scottish King James VI becoming King James I of England in 1603, to be ruled by an experienced monarch was much less traumatic for England than was for Scotland the departure of the head of state from Edinburgh to London. After 1707 of course an absentee monarchy became an absentee parliament, but in the period 1603 to 1707 it is perhaps a surprise that so many of the traditional and medieval-based symbols of Parliament remained constant, if occasionally re-worked in changing circumstances. -

Symbolism and Ritual in the 17Th Century Scottish Parliament

Symbolism and ritual in the seventeenth-century Scottish Parliament Alastair J. Mann (University of Stirling) Parliaments communicate with the people of their nations through a range of symbolic and ritualistic registers. The nature of symbolism and ceremony in the Scottish Parliament before the 1707 union with the parliament of England provides an interesting illustration of this communicative aspect.1 In particular seventeenth-century Scotland - an astonishingly traumatised place of political and religious strife – was home to a surprising reliance on rituals in spite of the atmosphere of conflict. In the last full century of this parliament’s long life, the impact of decades of revolution, warfare and economic collapse was even greater for Scotland than for England. Traditionally, in Scottish and English historiography, the woes of Scotland after 1603 are placed at the foot of government by absentee monarchy. Indeed although some seventeenth-century English contemporaries and modern English historians have reflected on the negative consequences of a Scottish King James VI becoming King James I of England in 1603, to be ruled by an experienced monarch was much less traumatic for England than was for Scotland the departure of the head of state from Edinburgh to London. After 1707 of course an absentee monarchy became an absentee parliament, but in the period 1603 to 1707 it is perhaps a surprise that so many of the traditional and medieval-based symbols of Parliament remained constant, if occasionally re-worked in changing circumstances. 1 For summaries and contrasts with the post 1999 Scottish Parliament see Alastair .J. Mann, ‘The Scottish Parliaments: the role of ritual and procession in the pre 1707 parliament and echoes in the new parliament of 1999’, in Rituals in Parliament: Political, Anthropological and Historical Perspectives on Europe and the United States, eds. -

Edinburgh, Scotland Edinburgh Is One of Europe’S Most Enchanting and Picturesque Cities Built Across 7 Hills and Overlook- Ing the Sea It Has Many a Story to Tell

Edinburgh, Scotland Edinburgh is one of Europe’s most enchanting and picturesque cities Built across 7 hills and overlook- ing the sea it has many a story to tell. From the Old Town jumble of medieval buildings stacked one against each other on the Royal Mile to the New Town Georgian grid like streets. This is a city of excitement and intrigue which is why it is so popular with tourists. Edinburgh’s nickname is ‘Auld Reekie’ which dates back to the times that living dwellings were heated with open fires. Thou- sands upon thousands of coal fires caused soot to accumulate in the city giving it its pet name. Edinburgh Old Town The entire city centre area that is found south of Princess Street. The old town section of Edinburgh is rather unique in its layout which is still typically medieval. It has many reformation era and other classi- cal buildings that have been preserved, and the area was declared a UNESCO world heritage site in 1995. The main road is the Royal Mile which has Edinburgh Castle at one end and the ruins of Holy- rood Abbey at the other. The Royal Mile forms a spine to the many narrow closes (alleyways) that lead downhill either side in a herringbone pattern and create easy shortcuts for people who are walking around the area. There are many large squares around the old town and each of these holds public buildings, such as St Giles Cathedral, Tron Kirk or the Supreme Courts. There are a number of other landmark locations here too, The Queen’s Edinburgh residence the Palace of Holyrood house, the royal museum of Scotland, the University of Edinburgh, and Surgeons hall. -

Nollaig Chridheil Agus Bliadhna Mhath Ùr

The Saltire December 2017 Nollaig Chridheil agus Bliadhna Mhath Ùr Christmas is about to descend upon us yet again - as every shop and TV station advert in the land has been reminding us for weeks already! Meanwhile, the last society event for calendar year 2017 has been crossed off the list and all is well with the world! (Well, it isn't, but you know what I mean!) It has been a busy year for the society. In an effort to boost numbers and find out what people want to do, we have held no less than TWENTY SEVEN events! We owe the committee in particular, but also the loyal band of followers that always seems to turn up and support us, a tremendous vote of thanks. We will do that properly at the AGM! All that effort has boosted numbers a little, although not as much as we hoped, and in the process, we have learned a fair bit about what people want and don't want to do, all of which I imagine will be taken into account by next year's committee, when the time comes to plan, what I imagine will be a much slimmed down events list for 2018. Some dates for your calendar: Friday 12 January 2018 - 1st pre-Burns Supper dance practice. Friday 19 January 2018 - 2nd pre-Burns Supper dance practice. Thursday 25 January 2018 - Burns Supper. Friday 16 February 2018 - Annual General meeting. Further details of all these events appear on our website as they become available. Page 1 of 9 The Saltire December 2017 The committee and former chieftains of the St Andrew Society, taking part in the Grand March. -

The Stone of Destiny at the United Nations

The Scotland-UN Committee The Stone of Destiny at the United Nations During the spring of 1981 it was brought to the Scotland-UN Committee's attention that the United Nations Educational Social and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) had set up a special committee to promote the return of objects of national cultural interest to their home countries. The moving spirit behind it was President Mobutu of Zaire, who in October 1973 had held an impassioned speech before the UN General Assembly in New York demanding the return of the works of art and objects of national importance that had been looted from Africa and other parts of the world during the colonial period. The committee consisted of 20 members, nominated by their governments. Its chairman at the time was Salah Stétié, a cultured Lebanese diplomat and writer. The object of the committee was to overcome the legal and chauvinist hurdles that prevent the return of objects such as the famous Mask of Benim to their native lands, the condition being that they must be objects of fundamental cultural significance, and have been removed in the course of colonial or other foreign occupation, or as a result of illegal export. The opportunity was too good to miss, and the Stone of Destiny was the obvious subject. The snag was that the committee was there to negotiate between governments, and not between governments and representatives of nations within composite states. It was perfectly clear from the start, therefore, that the chances of having the Westminster stone returned by this method were precisely nil, in a legal sense. -

PROCEEDINGS of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

PROCEEDINGS of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Our full archive of freely accessible articles covering Scottish archaeology and history is available at http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/archives/view/psas/volumes.cfm National Museums Scotland Chambers Street, Edinburgh www.socantscot.org Charity No SC 010440 TECHNICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE REGALIA OF SCOTLAND. 49 II. TECHNICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE REGALIA OF SCOTLAND. By ALEXANDER J. S. BROOK, F.S.A. SOOT (PLATES 1II-V.) In the inventories of the Koyal Wardrobe and Jewel-house between the years 15391 and 1579 the Crown, the Sceptre, and the Sword of State are included, but they are described in terms so general as to be almost valueless purpose excepth r whicr fo t efo h they were prepared. descriptioe Th n 1621i , whe r PatricnSi k Murra Elibanf yo k delivered 1 Inventur clethine th f eo g abilyamentis uthid an r graitriche th f th o excellen d an t mychti prince king James the fyft king of Scotland maid the xxv day of the monet f March ho MDXXXId e yeirGo th e f .o X than s hienebeinhi n gi s ward- robbis. JOWELLIS. ITEM ane crowne of gold sett with perle and precious stanis. Item in primis of diamentis tuenty. Item of fyue orient perle thre scoir and ancht wantand ane floure delice of gold. Ite septoue man r wit grete han . heie it perl e berealth f do an n ei d an l Ite swerdia mtw honouf so r with twa belti aule sth d belt wantand foure stuthis.