The Scottish Parliaments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Old and New Towns of Edinburgh World Heritage Site Management Plan

The Old and New Towns of Edinburgh World Heritage Site Management Plan July 2005 Prepared by Edinburgh World Heritage on behalf of the Scottish Ministers, the City of Edinburgh Council and the Minister for Media and Heritage Foreword en years on from achieving World Heritage Site status we are proud to present Edinburgh’s first World Heritage Site Management Plan. The Plan provides a framework T for conservation in the heart of Scotland’s capital city. The preparation of a plan to conserve this superb ‘world’ city is an important step on a journey which began when early settlers first colonised Castle Rock in the Bronze Age, at least 3,000 years ago. Over three millennia, the city of Edinburgh has been shaped by powerful historical forces: political conflict, economic hardship, the eighteenth century Enlightenment, Victorian civic pride and twentieth century advances in science and technology. Today we have a dynamic city centre, home to 24,000 people, the work place of 50,000 people and the focus of a tourism economy valued at £1 billion per annum. At the beginning of this new millennium, communication technology allows us to send images of Edinburgh’s World Heritage Site instantly around the globe, from the broadcasted spectacle of a Festival Fireworks display to the personal message from a visitor’s camera phone. It is our responsibility to treasure the Edinburgh World Heritage Site and to do so by embracing the past and enhancing the future. The World Heritage Site is neither a museum piece, nor a random collection of monuments. It is today a complex city centre which daily absorbs the energy of human endeavour. -

Development Brief Princes Street Block 10 Approved by the Planning Commitee 15 May 2008 DEVELOPMENT BRIEF BLOCK 10

Development Brief Princes Street Block 10 Approved by the Planning Commitee 15 May 2008 DEVELOPMENT BRIEF BLOCK 10 Contents Page 1.0 Introduction 2 2.0 Site and context 2 3.0 Planning Policy Context 4 4.0 Considerations 6 4.1 Architectural Interest 4.2 Land uses 4.4 Setting 4.5 Transport and Movement 4.12 Nature Conservation/Historic Gardens and Designed Landscapes 4.16 Archaeological Interests 4.17 Contaminated land 4.18 Sustainability 5.0 Development Principles 12 6.0 Implementation 16 1 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Following the Planning Committee approval of the City Centre Princes Street Development Framework (CCPSDF) on 4 October 2007, the Council have been progressing discussions on the individual development blocks contained within the Framework area. The CCPSDF set out three key development principles based on reconciling the needs of the historic environment with contemporary users, optimising the site’s potential through retail-led mixed uses and creating a high quality built environment and public realm. It is not for this development brief to repeat these principles but to further develop them to respond to this area of the framework, known as Block 10. 1.2 The purpose of the development brief is to set out the main planning and development principles on which development proposals for the area should be based. The development brief will be a material consideration in the determination of planning applications that come forward for the area. 2.0 Site and context The Site 2.1 The development brief area is situated at the eastern end of the city centre and is the least typical of all the development blocks within the CCPSDF area. -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRApHY PRIMARY SOURCEs Conversations and Correspondence with Lady Mary Whitley, Countess Mountbatten, Maitre Blum and Dr. Heald Judgements and Case Reports Newell, Ann: The Secret Life of Ellen, Lady Kilmorey, unpublished dissertation, 2016 Royal Archives, Windsor The Kilmorey Papers: Public Record Office of Northern Ireland The Teck Papers: Wellington College SECONDARY SOURCEs Aberdeen, Isobel. 1909. Marchioness of, Notes & Recollections. London: Constable. Annual Register Astle, Thomas. 1775. The Will of Henry VII. ECCO Print editions. Bagehot, Walter. 1867 (1872). The English Constitution. Thomas Nelson & Sons. Baldwin-Smith, Lacey. 1971. Henry VIII: The Mask of Royalty. London: Jonathan Cape. Benn, Anthony Wedgwood. 1993. Common Sense: A New Constitution for Britain, (with Andrew Hood). Brooke, the Hon. Sylvia Brooke. 1970. Queen of the Headhunters. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. Chamberlin, Frederick. 1925. The Wit & Wisdom of Good Queen Bess. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head. © The Author(s) 2017 189 M.L. Nash, Royal Wills in Britain from 1509 to 2008, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-60145-2 190 BIBLIOGRAPHY Chevenix-Trench, Charles. 1964. The Royal Malady. New York: Harcourt, Bruce & World Cronin, Vincent. 1964 (1990). Louis XIV. London: Collins Harvel. Davey, Richard. 1909. The Nine Days’ Queen. London: Methuen & Co. ———. 1912. The Sisters of Lady Jane Grey. New York: E.R. Dutton. De Lisle, Leanda. 2004. After Elizabeth: The Death of Elizabeth, and the Coming of King James. London: Harper Collins. Doran, John. 1875. Lives of the Queens of England of the House of Hanover, vols I & II. London: Richard Bentley & Sons. Edwards, Averyl. 1947. Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales. London/New York/ Toronto: Staples Press. -

Ward, Christopher J. (2010) It's Hard to Be a Saint in the City: Notions of City in the Rebus Novels of Ian Rankin. Mphil(R) Thesis

Ward, Christopher J. (2010) It's hard to be a saint in the city: notions of city in the Rebus novels of Ian Rankin. MPhil(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/1865/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] It’s Hard To Be A Saint In The City: Notions of City in the Rebus Novels of Ian Rankin Christopher J Ward Submitted for the degree of M.Phil (R) in January 2010, based upon research conducted in the department of Scottish Literature and Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow © Christopher J Ward, 2010 Contents Acknowledgements 3 Introduction: The Crime, The Place 4 The juncture of two traditions 5 Influence and intent: the origins of Rebus 9 Combining traditions: Rebus comes of age 11 Noir; Tartan; Tartan Noir 13 Chapter One: Noir - The City in Hard-Boiled Fiction 19 Setting as mode: urban versus rural 20 Re-writing the Western: the emergence of hard-boiled fiction 23 The hard-boiled city as existential wasteland 27 ‘Down these mean streets a man must -

Sir Walter Scott's Templar Construct

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. SIR WALTER SCOTT’S TEMPLAR CONSTRUCT – A STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY INFLUENCES ON HISTORICAL PERCEPTIONS. A THESIS PRESENTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY AT MASSEY UNIVERSITY, EXTRAMURAL, NEW ZEALAND. JANE HELEN WOODGER 2017 1 ABSTRACT Sir Walter Scott was a writer of historical fiction, but how accurate are his portrayals? The novels Ivanhoe and Talisman both feature Templars as the antagonists. Scott’s works display he had a fundamental knowledge of the Order and their fall. However, the novels are fiction, and the accuracy of some of the author’s depictions are questionable. As a result, the novels are more representative of events and thinking of the early nineteenth century than any other period. The main theme in both novels is the importance of unity and illustrating the destructive nature of any division. The protagonists unify under the banner of King Richard and the Templars pursue a course of independence. Scott’s works also helped to formulate notions of Scottish identity, Freemasonry (and their alleged forbearers the Templars) and Victorian behaviours. However, Scott’s image is only one of a long history of Templars featuring in literature over the centuries. Like Scott, the previous renditions of the Templars are more illustrations of the contemporary than historical accounts. One matter for unease in the early 1800s was religion and Catholic Emancipation. -

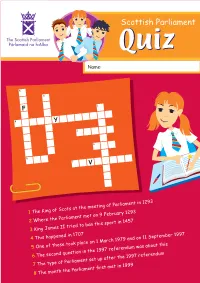

1 the King of Scots at the Meeting of Parliament in 1293 2 Where The

Name: F Y V 1 The King of Scots at the meeting of Parliament in 1293 2 Where the Parliament met on 9 February 1293 3 King James II tried to ban this sport in 1457 4 This happened in 1707 5 One of these took place on 1 March 1979 and on 11 September 1997 6 The second question in the 1997 referendum was about this 7 The type of Parliament set up after the 1997 referendum 8 The month the Parliament first met in 1999 What the Scottish Parliament can do The Scottish Parliament makes decisions that affect matters. our everyday lives and can______________________ pass laws on different things. These are called Some of these matters are: . The Scottish Parliament cannot make laws_________________ on reserved matters. These are dealt with by the Some examples of reserved matters are: The Honours of Scotland The ‘Honours of Scotland’ sculpture was created by silversmith ________________________________. The sculpture was presented to the Scottish Parliament by HM the ______________ to mark the opening of the Scottish Parliament building on Saturday 9 October 200_. The new sculpture is a reminder of the original three Honours of Scotland or the Crown Jewels – the Crown, the Sword and the Sceptre. Label the picture to show the three parts of the ‘Honours’. 1 1 ______________________________________ 2 2 ______________________________________ 3 ______________________________________ 3 What the Scottish Parliament can do The Scottish Parliament makes decisions that affect Passing laws in the Scottish Parliament matters. our everyday lives and can______________________ pass laws on different things. These are called New laws start as a proposal called a B_ _ _ . -

The Transformation of Drumlanrig Castle at the End of Seventeenth-Century

First Construction History Conference Queens' College, Cambridge, 11th -12th of April 2014 González-Longo The transformation of Drumlanrig Castle at the end of seventeenth-century Cristina González-Longo, Department of Architecture, University of Strathclyde Abstract The transformation of Drumlanrig Castle between 1679-98 makes it one of the most original and interesting buildings of its time in Britain. It was carried out at almost the same time as the Royal Palace of Holyrood, whose design, construction and procurement influenced the making of Drumlanrig. James Smith, one of the mason-contractors at Holyrood, went to work at Drumlanrig as an independent architect for the first time, providing a unique design that was in continuity with local practices but also aware of contemporary Continental architectural developments. The careful selection of craftsmen, techniques and materials make this building one of the finest in Scotland. Although the original drawings and accounts of the project have now disappeared, it is possible to trace the history of its design and construction through a series of documents and drawings at Drumlanrig Castle and by looking at the building itself. This paper will unravel the transformation of the building at the end of seventeenth-century, identifying the people, skills, materials, technologies and practices involved and discussing how the design ideas were implemented during the construction. Figure 1: North elevation of Drumlanrig Castle Introduction John Summerson considered Drumlanrig Castle the most remarkable building emerging from the tradition initiated by the King Mastermason William Wallace (d.1631), ‘the last great gesture of the Scottish castle style’ and ‘obstinately Scottish’.[1] He did not make any reference to the fact that the building incorporates an earlier building, which makes it even 1 First Construction History Conference Queens' College, Cambridge, 11th -12th of April 2014 González-Longo more remarkable. -

The Highland Clans of Scotland

:00 CD CO THE HIGHLAND CLANS OF SCOTLAND ARMORIAL BEARINGS OF THE CHIEFS The Highland CLANS of Scotland: Their History and "Traditions. By George yre-Todd With an Introduction by A. M. MACKINTOSH WITH ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS, INCLUDING REPRODUCTIONS Of WIAN'S CELEBRATED PAINTINGS OF THE COSTUMES OF THE CLANS VOLUME TWO A D. APPLETON AND COMPANY NEW YORK MCMXXIII Oft o PKINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS PAGE THE MACDONALDS OF KEPPOCH 26l THE MACDONALDS OF GLENGARRY 268 CLAN MACDOUGAL 278 CLAN MACDUFP . 284 CLAN MACGILLIVRAY . 290 CLAN MACINNES . 297 CLAN MACINTYRB . 299 CLAN MACIVER . 302 CLAN MACKAY . t 306 CLAN MACKENZIE . 314 CLAN MACKINNON 328 CLAN MACKINTOSH 334 CLAN MACLACHLAN 347 CLAN MACLAURIN 353 CLAN MACLEAN . 359 CLAN MACLENNAN 365 CLAN MACLEOD . 368 CLAN MACMILLAN 378 CLAN MACNAB . * 382 CLAN MACNAUGHTON . 389 CLAN MACNICOL 394 CLAN MACNIEL . 398 CLAN MACPHEE OR DUFFIE 403 CLAN MACPHERSON 406 CLAN MACQUARIE 415 CLAN MACRAE 420 vi CONTENTS PAGE CLAN MATHESON ....... 427 CLAN MENZIES ........ 432 CLAN MUNRO . 438 CLAN MURRAY ........ 445 CLAN OGILVY ........ 454 CLAN ROSE . 460 CLAN ROSS ........ 467 CLAN SHAW . -473 CLAN SINCLAIR ........ 479 CLAN SKENE ........ 488 CLAN STEWART ........ 492 CLAN SUTHERLAND ....... 499 CLAN URQUHART . .508 INDEX ......... 513 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Armorial Bearings .... Frontispiece MacDonald of Keppoch . Facing page viii Cairn on Culloden Moor 264 MacDonell of Glengarry 268 The Well of the Heads 272 Invergarry Castle .... 274 MacDougall ..... 278 Duustaffnage Castle . 280 The Mouth of Loch Etive . 282 MacDuff ..... 284 MacGillivray ..... 290 Well of the Dead, Culloden Moor . 294 Maclnnes ..... 296 Maclntyre . 298 Old Clansmen's Houses 300 Maclver .... -

HISTORY Scheinker Syndrome (GSS) Consequence Ofexposure Totheseinfected Individuals

J R Coll Physicians Edinb 2005; 35:268–274 PAPER © 2005 Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh Dangerous dissections: the hazard from bodies supplied to Edinburgh anatomists, winter session, 1848–9 MH Kaufman School of Biomedical and Clinical Laboratory Sciences, University of Edinburgh,Scotland ABSTRACT After the 1832 Anatomy Act,all bodies that were to be used by medical Correspondence to MH Kaufman, students for dissection were supplied to Schools of Anatomy based on their needs. School of Biomedical and Clinical During the Winter Session of 1848–9, a high proportion of the bodies supplied to Laboratory Sciences, Hugh Robson the University of Edinburgh, and the majority of those supplied to the Argyle Building, George Square, Edinburgh Square School had died of an infectious disease. Most had died from cholera, while EH8 9XD others had died of typhus, tuberculosis or other infectious diseases. These bodies tel. +44 (0)131 650 3113 were not embalmed before dissection. Therefore, both medical students and their teachers in Departments of Anatomy, in addition to those in the hospitals in which fax. +44 (0)131 650 3711 they had died, would have been at risk of becoming infected or even dying as a consequence of exposure to these infected individuals. e-mail [email protected] KEYWORDS Infected bodies, Schools of Anatomy, cholera, typhus, tuberculosis, bodies not embalmed, risk of infection LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS Creutzfeldt Jacob Disease (CJD), Gerstmann-Straussler- Scheinker syndrome (GSS) DECLARATION OF INTEREST No conflict of interests declared. Shortly after the implementation of the 1832 Anatomy and therefore had relatively little difficulty in obtaining an Act,1 there was considerable concern in the various adequate number for this purpose, this tended to be the extra-mural schools in Edinburgh, all of which were exception rather than the rule. -

Scotland Scotland DEPART DATE: 04/10/2022 RETURN DATE: 04/18/2022 NUMBER of DAYS: 9

–––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– TRIP DETAILS –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– TEAM NAME: EPYSA Boys 2009 & 2010 DESTINATION: Scotland Scotland DEPART DATE: 04/10/2022 RETURN DATE: 04/18/2022 NUMBER OF DAYS: 9 YOUR DAY-BY-DAY ADVENTURE DAY 1 DAY 5 Flight to Scotland Breakfast at Hotel Please note: the final itinerary may be slightly Training Session different from this program. The final itinerary will be Scottish Football Museum Witness the thousands of determined based on the size of the group, any objects on display, tracing the history of football in adjustments that are required (such as adding Scotland and highlights some of the most memorable additional matches), and the final schedule of the games and players. Sit in what was the original matches. (If additional matches are required, then dressing room from the old Hampden and listen to some sightseeing content will be replaced by the Craig Brown addressing -

Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh SCOTTISH PARLIAMENT in EDINBURGH

Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh SCOTTISH PARLIAMENT IN EDINBURGH Nestling within the un- usual architecture of the new Scottish Parliament 3 is Queensberry House, 5 a listed 17th-century 1 building, now restored. 2 4 7 6 8 Aerial photograph and In May 1999, after almost 300 years of rule lan architects Enric Miralles and Benedetta cross section through from Westminster, the first elections were Tagliabue. Inspired by the landscape around garden foyer 1 Public entrance held for a Scottish parliament with executive Edinburgh and the work of the Scottish archi - 2 Plenary hall powers on regional affairs. This devolution tect and artist Charles Rennie Mackintosh, 3 Media building within the United Kingdom, achieved through they came up with a design for a combination 4 Four 'towers' with debating chambers a public referendum, was also to be reflect- of separate, but closely grouped buildings. and offices of the ed in the architecture of the new parliament Organic shapes and a collage-like diversity ministers building. The new building, standing at the give the complex its characteristic outward 5 Canongate Building 6 Garden foyer end of the Royal Mile and in close proximity expression. 7 Queensberry House to Holyrood Palace, was designed by Cata - 8 Offices of the MPs 4 7 6 1 · www.euro-inox.org © Euro Inox 2009 SCOTTISH PARLIAMENT IN EDINBURGH Oak, granite, sandstone, concrete, glass and stainless steel were the materials used in the building – all meeting the rigorous sustainability and environmental standards required, and also the demands in terms of quality and workmanship. Twelve skylights shaped like giant leaves dominate the impression in the central gar- den foyer that is shared by the individual buildings. -

Strathprints Institutional Repository

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Strathclyde Institutional Repository Strathprints Institutional Repository Gonzalez-Longo, Cristina (2008) Conserving, Reinstating and Converting Queensberry House. In: Proceedings 8th International Seminar on Structural Masonry (ISSM 08). UNSPECIFIED. ISBN 978-975-561-342-0 Strathprints is designed to allow users to access the research output of the University of Strathclyde. Copyright c and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. You may not engage in further distribution of the material for any profitmaking activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute both the url (http:// strathprints.strath.ac.uk/) and the content of this paper for research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Any correspondence concerning this service should be sent to Strathprints administrator: mailto:[email protected] http://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/ Conserving, Reinstating and Converting Queensberry House Cristina GONZÁLEZ-LONGO1 ABSTRACT This paper discusses the work that the author has carried out as project and resident architect for the conversion of Queensberry House, a 17th century Grade A-listed townhouse, as part of the new Scottish Parliament at Holyrood, Edinburgh. The complex stratification of this fine masonry building together with severe water penetration caused major problems when carrying out the works. The richness of the original masonry, the abusive additions and reconstruction over the centuries, like the late conversion to hospital, and the way the building fabric was conserved and reinstated are illustrated.