UNIQUELY SCOTTISH the Slow Road to Decline Monarchscottish to Speakgaelic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Royal Banners 1199–Present

British Royal Banners 1199 – Present Geoff Parsons & Michael Faul Abstract The presentation begins with the (accepted) date of 1199, the death of King Richard I, the first king known to have used the three gold lions on red. It continues to show how King Edward III added the French Royal Arms, consequent to his claim to the French throne. There is then the change from “France Ancient” to “France Modern” by King Henry IV in 1405, which set the pattern of the arms and the standard for the next 198 years. The story then proceeds to show how, over the ensuing 234 years, there were no fewer than six versions of the standard until the adoption of the present pattern in 1837. The presentation includes pictures of all the designs, noting that, in the early stages, the arms appeared more often as a surcoat than a flag. There is also some anecdotal information regarding the various patterns. Anne (1702–1714) Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 799 British Royal Banners 1199 – Present Figure 1 Introduction The presentation begins with the (accepted) date of 1199, the death of King Richard I, the first king known to have used the three gold lions on red. Although we often refer to these flags as Royal Standards, strictly speaking, they are not standard but heraldic banners which are based on the Coats of Arms of the British Monarchs. Figure 2 William I (1066–1087) The first use of the coats of arms would have been exactly that, worn as surcoats by medieval knights. -

The Story of the Stars & Stripes

The Story of the Stars & Stripes By the US Marine Corps The story of the origin of our national flag parallels the story of the origin of our country. As our country received its birthright from the peoples of many lands who were gathered on these shores to found a new nation, so did the pattern of the Stars and Stripes rise from several origins back in the mists of antiquity to become emblazoned on the standards of our infant Republic. The star is a symbol of the heavens and the divine goal to which man has aspired from time immemorial; the stripe is symbolic of the rays of light emanating from the sun. Both themes have long been represented on the standards of nations, from the banners of the astral worshippers of ancient Egypt and Babylon to the 12-starred flag of the Spanish Conquistadors under Cortez. Continuing in favor, they spread to the striped standards of Holland and the West Indian Company in the 17th century and to the present patterns of stars and stripes on the flags of several nations of Europe, Asia, and the Americas. The first flags adopted by our Colonial forefathers were symbolic of their struggles with the wilderness of a new land. Beavers, pine trees, rattlesnakes, anchors, and various like insignia with mottoes such as “Hope”, “Liberty”, “Appeal to Heaven” or “Don’t Tread on Me” were affixed to the different banners of Colonial America. The first flag of the colonists to have any resemblance to the present Stars and Stripes was the Grand Union flag, sometimes referred to as the “Congress Colors”. -

The Arms of the Baronial and Police Burghs of Scotland

'^m^ ^k: UC-NRLF nil! |il!|l|ll|ll|l||il|l|l|||||i!|||!| C E 525 bm ^M^ "^ A \ THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND Of this Volume THREE HUNDRED AND Fifteen Copies have been printed, of which One Hundred and twenty are offered for sale. THE ARMS OF THE BARONIAL AND POLICE BURGHS OF SCOTLAND BY JOHN MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T. H. J. STEVENSON AND H. W. LONSDALE EDINBURGH WILLIAM BLACKWOOD & SONS 1903 UNIFORM WITH THIS VOLUME. THE ARMS OF THE ROYAL AND PARLIAMENTARY BURGHS OF SCOTLAND. BY JOHN, MARQUESS OF BUTE, K.T., J. R. N. MACPHAIL, AND H. W. LONSDALE. With 131 Engravings on Wood and 11 other Illustrations. Crown 4to, 2 Guineas net. ABERCHIRDER. Argent, a cross patee gules. The burgh seal leaves no doubt of the tinctures — the field being plain, and the cross scored to indicate gules. One of the points of difference between the bearings of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs on the one hand and those of the I Police Burghs on the other lies in the fact that the former carry castles and ships to an extent which becomes almost monotonous, while among the latter these bearings are rare. On the other hand, the Police Burghs very frequently assume a charge of which A 079 2 Aberchirder. examples, in the blazonry of the Royal and Parliamentary Burghs, are very rare : this is the cross, derived apparently from the fact that their market-crosses are the most prominent of their ancient monuments. In cases where the cross calvary does not appear, a cross of some other kind is often found, as in the present instance. -

THE EAST LOTHIAN FLAG COMPETITION the Recent

THE EAST LOTHIAN FLAG COMPETITION The recent competition held to select a flag for the county of East Lothian, elicited four finalists; three of these were widely criticised for falling short of good design practice, as promoted for several years, by such bodies as the North American Vexillological Association and the Flag Institute. The latter’s Creating Local & Community Flags guide , as recently advertised by the Flag Institute's official Twitter feed on Monday 8th October 2018, states on page 7, that "Designs making it to the shortlist of finalists must meet Flag Institute design guidelines to ensure that all potential winning designs are capable of being registered." and further notes that "Flags are intended to perform a specific, important function. In order to do this there are basic design standards which need to be met." Page 8 of the same guide, also declares, "Before registering a new flag on the UK Flag Registry the Flag Institute will ensure that a flag design: Meets basic graphical standards." This critique demonstrates how the three flags examined, do not meet many of the basic design standards and therefore do not perform the specific and important intended functions. As a result, on its own grounds, none of the three can be registered by the Flag Institute. Flag B Aside from the shortcomings of its design, Flag B fails to meet the Flag Institute's basic requirement that any county flag placed on the UK Flag Registry cannot represent a modern administrative area. The Flag Institute’s previously cited, community flag guide, describes on page 6, the categories of flags that may be registered; "There are three types of flag that might qualify for inclusion in the UK Flag Registry: local community flags (including cities, towns and villages), historic county flags and flags for other types of traditional areas, such as islands or provinces. -

![Scotland [ˈskɑtlənd] (Help·Info) (Gaelic: Alba) Is a Country In](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4036/scotland-sk-tl-nd-help%C2%B7info-gaelic-alba-is-a-country-in-414036.webp)

Scotland [ˈskɑtlənd] (Help·Info) (Gaelic: Alba) Is a Country In

SCOTLAND The national flag of Scotland, known as the Saltire or St. Andrew's Cross, dates (at least in legend) from the 9th century, and is thus the oldest national flag still in use. St Andrew's Day, 30 November, is the national day, although Burns' Night tends to be more widely observed. Tartan Day is a recent innovation from Canada. Scotland is a country in northwest Europe that occupies the northern third of the island of Great Britain. It is part of the United Kingdom, and shares a land border to the south with England. It is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the southwest. In addition to the mainland, Scotland consists of over 790 islands including the Northern Isles and the Hebrides. Scotland contains the most mountainous terrain in Great Britain. Located at the western end of the Grampian Mountains, at an altitude of 1344 m, Ben Nevis is the highest mountain in Scotland and Great Britain. The longest river in Scotland is River Tay, which is 193 km long and the largest lake is Loch Lomond (71.1 km2). However, the most famous lake is Loch Ness, a large, deep, freshwater loch in the Scottish Highlands extending for approximately 37 km southwest of Inverness. Loch Ness is best known for the alleged sightings of the legendary Loch Ness Monster, also known as "Nessie". One of the most iconic images of Nessie is known as the 'Surgeon's Photograph', which many formerly considered to be good evidence of the monster. -

The Arms of the Scottish Bishoprics

UC-NRLF B 2 7=13 fi57 BERKELEY LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A \o Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/armsofscottishbiOOIyonrich /be R K E L E Y LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORN'A h THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS. THE ARMS OF THE SCOTTISH BISHOPRICS BY Rev. W. T. LYON. M.A.. F.S.A. (Scot] WITH A FOREWORD BY The Most Revd. W. J. F. ROBBERDS, D.D.. Bishop of Brechin, and Primus of the Episcopal Church in Scotland. ILLUSTRATED BY A. C. CROLL MURRAY. Selkirk : The Scottish Chronicle" Offices. 1917. Co — V. PREFACE. The following chapters appeared in the pages of " The Scottish Chronicle " in 1915 and 1916, and it is owing to the courtesy of the Proprietor and Editor that they are now republished in book form. Their original publication in the pages of a Church newspaper will explain something of the lines on which the book is fashioned. The articles were written to explain and to describe the origin and de\elopment of the Armorial Bearings of the ancient Dioceses of Scotland. These Coats of arms are, and have been more or less con- tinuously, used by the Scottish Episcopal Church since they came into use in the middle of the 17th century, though whether the disestablished Church has a right to their use or not is a vexed question. Fox-Davies holds that the Church of Ireland and the Episcopal Chuich in Scotland lost their diocesan Coats of Arms on disestablishment, and that the Welsh Church will suffer the same loss when the Disestablishment Act comes into operation ( Public Arms). -

On the Concepts of 'Sovereign' and 'Great' Orders

ON THE CONCEPTS OF ‘SOVEREIGN’ AND ‘GREAT’ ORDERS Antti Matikkala The only contemporary order of knighthood to include the word ‘sovereign’ in its name is the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of St John of Jerusalem of Rhodes and Malta. Sovereignty is here heraldically exemplified by the Grand Master’s use of the closed crown. Its Constitutional Charter and Code explains that the order ‘be- came sovereign on the islands of Rhodes and later of Malta’, and makes the follow- ing statement about its sovereignty: ‘The Order is a subject of international law and exercises sovereign functions.’1 However, the topic of this article is not what current scholarship designates as military-religious orders of knighthood, or simply military orders, but monarchical orders. To quote John Anstis, Garter King of Arms,2 a monarchical order can be defined in the following terms: a Brotherhood, Fellowship, or Association of a certain Number of actual Knights; sub- jected under a Sovereign, or Great Master, united by particular Laws and Statutes, peculiar to that Society, not only distinguished by particular Habits, Ensigns, Badges or Symbols, which usually give Denomination to that Order; but having a Power, as Vacancies happen in their College, successively, of nominating, or electing proper Per- sons to succeed, with Authority to assemble, and hold Chapters. The very concept of sovereignty is ambiguous. A recent collection of essays has sought to ‘dispel the illusion that there is a single agreed-upon concept of sovereignty for which one could offer of a clear definition’.3 To complicate the issue further, historical and theoretical discussions on sovereignty, including those relating to the Order of Malta, concentrate mostly on its relation to the modern concept of state, leaving the supposed sovereignty of some of the monarchical orders of knighthood an unexplored territory. -

Saint Andrew's Society of San Francisco

Incoming 2nd VP Welcome Message By Alex Sinclair ince being welcomed to the St. Andrew’s community almost Stwo years ago, I have been filled with the warmth and joy that this society and its members bring to the San Francisco Bay Area. From dance, music, poetry, history, charity, and edu- cation the charity’s past 155 years has celebrated Scottish cul- ture in its contributions to the people of California. I have been grateful to the many friendly faces and experiences I have had since rediscovering the Scottish identity while at the society. I appreciate everyone who has supported my nomination as an officer within the organisation, and I will try my best no matter Francesca McCrossan, President your vote to support your needs as members and of the success November 2020 of the charity at large. President’s Message Being an officer at the society tends to need a wide range of skills and challenges to meet the needs of the membership and Dear St. Andrew’s Society, the various programs and events we run through the year, in the Looking towards the New Year time of Covid even more so. In my past, I have been a chef, a musician, a filmmaker, a tour manager, a marketeer, an entre- t the last November Members meeting, I was reelected as preneur, an archivist and a specialist in media licencing and Ayour President, and I thank the Members for the honor to digital asset management. I hold an NVQ in Hospitality and Ca- be able to serve the Society for another year. -

11-20 November Issue

The British Isles Historic Society Heritage, History, Traditions & Customs 11-20 November Issue St. Andrew deeming himself unworthy to be crucified in the same manner as Jesus Christ. Instead, he was nailed St. Andrew has been celebrated upon an X-shaped cross on 30 November 60AD in in Scotland for over a thousand years, Greece, and thus the diagonal cross of the saltire with feasts being held in his honour as was adopted as his symbol, and the last day in far back as the year 1000 AD. November designated his saint day. However, it wasn’t until 1320, According to legend, Óengus II, king of Picts when Scotland’s independence was and Scots, led an army against the Angles, a declared with the signing of The Germanic people that invaded Britain. The Scots Declaration of Arbroath, that he officially became were heavily outnumbered, and Óengus prayed the Scotland’s patron saint. Since then St Andrew has night before battle, vowing to name St. Andrew the become tied up in so much of Scotland. The flag of patron saint of Scotland if they won. Scotland, the St. Andrew’s Cross, was chosen in honour of him. Also, the ancient town of St Andrews On the day of the battle, white clouds formed was named due to its claim of being the final resting an X in the sky. The clouds were thought to place of St. Andrew. represent the X-shaped cross where St. Andrew was crucified. The troops were inspired by the apparent According to Christian teachings, Saint Andrew divine intervention, and they came out victorious was one of Jesus Christ’s twelve disciples. -

Bibliography

BIbLIOGRApHY PRIMARY SOURCEs Conversations and Correspondence with Lady Mary Whitley, Countess Mountbatten, Maitre Blum and Dr. Heald Judgements and Case Reports Newell, Ann: The Secret Life of Ellen, Lady Kilmorey, unpublished dissertation, 2016 Royal Archives, Windsor The Kilmorey Papers: Public Record Office of Northern Ireland The Teck Papers: Wellington College SECONDARY SOURCEs Aberdeen, Isobel. 1909. Marchioness of, Notes & Recollections. London: Constable. Annual Register Astle, Thomas. 1775. The Will of Henry VII. ECCO Print editions. Bagehot, Walter. 1867 (1872). The English Constitution. Thomas Nelson & Sons. Baldwin-Smith, Lacey. 1971. Henry VIII: The Mask of Royalty. London: Jonathan Cape. Benn, Anthony Wedgwood. 1993. Common Sense: A New Constitution for Britain, (with Andrew Hood). Brooke, the Hon. Sylvia Brooke. 1970. Queen of the Headhunters. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. Chamberlin, Frederick. 1925. The Wit & Wisdom of Good Queen Bess. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head. © The Author(s) 2017 189 M.L. Nash, Royal Wills in Britain from 1509 to 2008, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-60145-2 190 BIBLIOGRAPHY Chevenix-Trench, Charles. 1964. The Royal Malady. New York: Harcourt, Bruce & World Cronin, Vincent. 1964 (1990). Louis XIV. London: Collins Harvel. Davey, Richard. 1909. The Nine Days’ Queen. London: Methuen & Co. ———. 1912. The Sisters of Lady Jane Grey. New York: E.R. Dutton. De Lisle, Leanda. 2004. After Elizabeth: The Death of Elizabeth, and the Coming of King James. London: Harper Collins. Doran, John. 1875. Lives of the Queens of England of the House of Hanover, vols I & II. London: Richard Bentley & Sons. Edwards, Averyl. 1947. Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales. London/New York/ Toronto: Staples Press. -

Sir Walter Scott's Templar Construct

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. SIR WALTER SCOTT’S TEMPLAR CONSTRUCT – A STUDY OF CONTEMPORARY INFLUENCES ON HISTORICAL PERCEPTIONS. A THESIS PRESENTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY AT MASSEY UNIVERSITY, EXTRAMURAL, NEW ZEALAND. JANE HELEN WOODGER 2017 1 ABSTRACT Sir Walter Scott was a writer of historical fiction, but how accurate are his portrayals? The novels Ivanhoe and Talisman both feature Templars as the antagonists. Scott’s works display he had a fundamental knowledge of the Order and their fall. However, the novels are fiction, and the accuracy of some of the author’s depictions are questionable. As a result, the novels are more representative of events and thinking of the early nineteenth century than any other period. The main theme in both novels is the importance of unity and illustrating the destructive nature of any division. The protagonists unify under the banner of King Richard and the Templars pursue a course of independence. Scott’s works also helped to formulate notions of Scottish identity, Freemasonry (and their alleged forbearers the Templars) and Victorian behaviours. However, Scott’s image is only one of a long history of Templars featuring in literature over the centuries. Like Scott, the previous renditions of the Templars are more illustrations of the contemporary than historical accounts. One matter for unease in the early 1800s was religion and Catholic Emancipation. -

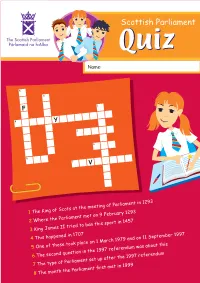

1 the King of Scots at the Meeting of Parliament in 1293 2 Where The

Name: F Y V 1 The King of Scots at the meeting of Parliament in 1293 2 Where the Parliament met on 9 February 1293 3 King James II tried to ban this sport in 1457 4 This happened in 1707 5 One of these took place on 1 March 1979 and on 11 September 1997 6 The second question in the 1997 referendum was about this 7 The type of Parliament set up after the 1997 referendum 8 The month the Parliament first met in 1999 What the Scottish Parliament can do The Scottish Parliament makes decisions that affect matters. our everyday lives and can______________________ pass laws on different things. These are called Some of these matters are: . The Scottish Parliament cannot make laws_________________ on reserved matters. These are dealt with by the Some examples of reserved matters are: The Honours of Scotland The ‘Honours of Scotland’ sculpture was created by silversmith ________________________________. The sculpture was presented to the Scottish Parliament by HM the ______________ to mark the opening of the Scottish Parliament building on Saturday 9 October 200_. The new sculpture is a reminder of the original three Honours of Scotland or the Crown Jewels – the Crown, the Sword and the Sceptre. Label the picture to show the three parts of the ‘Honours’. 1 1 ______________________________________ 2 2 ______________________________________ 3 ______________________________________ 3 What the Scottish Parliament can do The Scottish Parliament makes decisions that affect Passing laws in the Scottish Parliament matters. our everyday lives and can______________________ pass laws on different things. These are called New laws start as a proposal called a B_ _ _ .