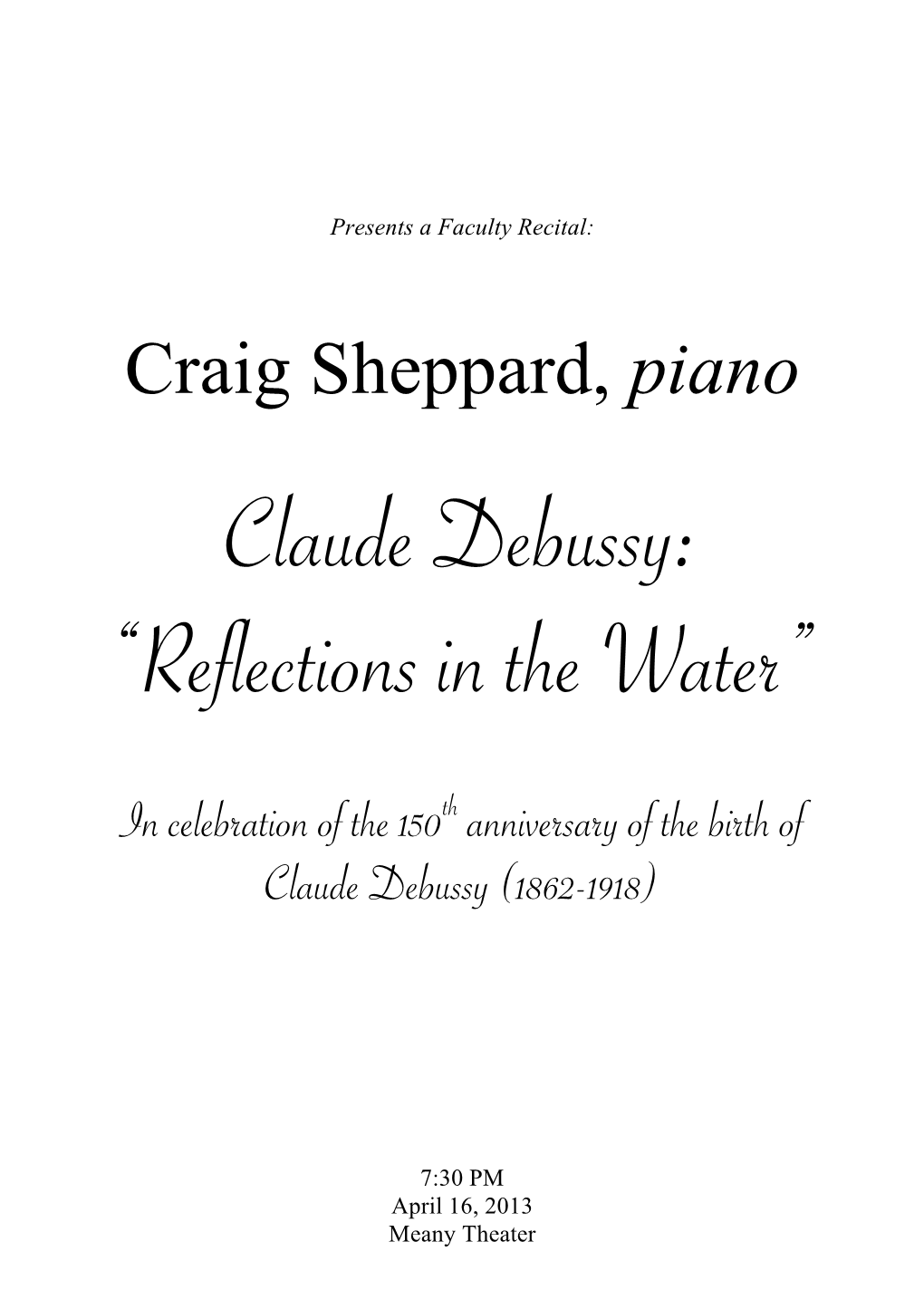

Claude Debussy: “Reflections in the Water”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Claude Debussy in 2018: a Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies

19-23/03/18 CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN 2018: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION ABSTRACTS AND BIOGRAPHIES Claude Debussy in 2018: A Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies I. Debussy Perspectives, 1918-2018 RNCM, Manchester Monday, 19 March Paper session A: Debussy’s Style in History, Conference Room, 2.00-5.00 Chair: Marianne Wheeldon 2.00-2.30 – Mark DeVoto (Tufts University), ‘Debussy’s Evolving Style and Technique in Rodrigue et Chimène’ Claude Debussy’s Rodrigue et Chimène, on which he worked for two years in 1891-92 before abandoning it, is the most extensive of more than a dozen unfinished operatic projects that occupied him during his lifetime. It can also be regarded as a Franco-Wagnerian opera in the same tradition as Lalo’s Le Roi d’Ys (1888), Chabrier’s Gwendoline (1886), d’Indy’s Fervaal (1895), and Chausson’s Le Roi Arthus (1895), representing part of the absorption of the younger generation of French composers in Wagner’s operatic ideals, harmonic idiom, and quasi-medieval myth; yet this kinship, more than the weaknesses of Catulle Mendès’s libretto, may be the real reason that Debussy cast Rodrigue aside, recognising it as a necessary exercise to be discarded before he could find his own operatic voice (as he soon did in Pelléas et Mélisande, beginning in 1893). The sketches for Rodrigue et Chimène shed considerable light on the evolution of Debussy’s technique in dramatic construction as well as his idiosyncratic approach to tonal form. Even in its unfinished state — comprising three out of a projected four acts — the opera represents an impressive transitional stage between the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra (1890) and the full emergence of his genius, beginning with the String Quartet (1893) and the Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune (1894). -

Stylistic Influences and Musical Quotations in Claude Debussy's Children's Corner and La Boîte A

EVOCATIONS FROM CHILDHOOD: STYLISTIC INFLUENCES AND MUSICAL QUOTATIONS IN CLAUDE DEBUSSY’S CHILDREN’S CORNER AND LA BOÎTE À JOUJOUX Hsing-Yin Ko, M.B., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2011 APPROVED: Vladimir Viardo, Major Professor Elvia Puccinelli, Minor Professor Frank Heidlberger, Committee Member Jesse Eschbach, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Lynn Eustis, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of College of Music James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Ko, Hsing-Yin, Evocations from Childhood: Stylistic Influences and Musical Quotations in Claude Debussy’s Children’s Corner and La Boîte à Joujoux. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2011, 44 pp., 33 musical examples, bibliographies, 43 titles. Claude Debussy is considered one of the most influential figures of the late 19th century and early 20th centuries. Among the various works that he wrote for the piano, Children’s Corner and La Boîte à joujoux distinguish themselves as being evocative of childhood. However, compared to more substantial works like Pelléas et Mélisande or La Mer, his children’s piano music has been underrated and seldom performed. Children’s Corner and La Boîte à joujoux were influenced by a series of eclectic sources, including jazz, novel “views” from Russian composers, and traditional musical elements such as folk songs and Eastern music. The study examines several stylistic parallels found in these two pieces and is followed by a discussion of Debussy’s use of musical quotations and allusions, important elements used by the composer to achieve what could be dubbed as a unique “children’s wonderland.” Copyright 2011 by Hsing-Yin Ko ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES ............................................................................................... -

Narrative Expansion in the Trois Chansons De Bilitis

Debussy as Storyteller: Narrative Expansion In the Trois Chansons de Bilitis William Gibbons Every song cycle presents its audience with a narrative. Such an idea is hardly new; indeed, the idea of an unfolding plot or unifying concept (textual or musical) is central to the concept of the song cycle as opposed to a collection of songs, at least after the mid-nineteenth century.l A great deal of musico logical literature devoted to song cycles is aimed at demonstrating that they are cohesive wholes, often connected both musically, by means of key relationships, motivic recall, and similar techniques, and textually, by means of the creation of an overarching plot or concept.2 One type of narrative results from a poetic unit being set to music in its complete state, without alteration. I am interested here, however, in another type of narrative-one that unfolds when a composer chooses to link previously unrelated poems musically, or when a poetic cycle is altered by rearrangement of the songs or omission of one or more poems. This type of song cycle may create its own new narrative, distinct from its literary precursors. In an effort to demonstrate the internally cohesive qualities of these song cycles, typical analyses assume that the narrative is contained entirely within the musical cycle itself-that is, that it makes no external references. I do not mean to disparage this type of analysis, which often yields insight ful results; however, this approach ignores the audience's ability to make intertextual connections beyond the bounds of the song cycle at hand. -

Debussy's Piano Music

CONSIDERATIONS FOR PEDALLING DEBUSSY'S PIANO MUSIC Maria Metaxaki DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS CITY UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC March 2005 ALL MISSING PAGES ARE BLANK TABLE OF CONTENTS FIGURES iii LIST OF TABLES AND ........................................................ EXAMPLES iv LIST OF MUSICAL ......................................................... vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................. viii DECLARATION ...................................................................................................... ABSTRACT ix ..................................................................................... I INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 1 Piano 'Without Hammers: Pianos in Debussy's Time 7 CHAPTER -The ......... CHAPTER 2- Gamelan Music and the 'Vibrations in the Air ...................... 15 CHAPTER 3- 'Faites Conflance A Votre Oreille': Pedalling Techniques in Debussy's Piano Music 29 ................................................... in Welte Mignon Piano Rolls 57 CHAPTER 4- Debussy's Use of the Pedals the ... Scores: Indications for Pedalling 75 CHAPTER 5- Debussy's .......................... CHAPTER 6- Pedalling in 'La Cath6drale engloutie ................................ 99 BIBLIOGRAPHY 107 ........................................................................... DISCOGRAPHY 113 ............................................................................ APPENDIX 1- Musical Examples 115 ..................................................... -

Parting the Veils of Debussy's Voiles Scottish Music Review

Parting the Veils of Debussy’s Voiles David Code Lecturer in Music, University of Glasgow Scottish Music Review Abstract Restricted to whole-tone and pentatonic scales, Debussy’s second piano prelude, Voiles, often serves merely to exemplify both his early modernist musical language and his musical ‘Impressionism’. Rejecting both arid theoretical schemes and vague painterly visions, this article reconsiders the piece as an outgrowth of the particular Mallarméan lessons first instantiated years earlier in the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. In developing a conjecture by Renato di Benedetto, and taking Mallarmé’s dance criticism as stimulus to interpretation, the analysis makes distinctive use of video-recorded performance to trace the piece’s choreography of hands and fingers on the keyboard’s music-historical stage. A contribution by example to recent debates about the promises and pitfalls of performative or ‘drastic’ analysis (to use the term Carolyn Abbate adopted from Vladimir Jankélévitch), the article ultimately adumbrates, against the background of writings by Dukas and Laloy, a new sense of Debussy’s pianistic engagement with the pressing questions of his moment in the history of modernism. I will try to glimpse, through musical works, the multiple movements that gave birth to them, as well as all that they contain of the inner life: is that not rather more interesting than the game that consists of taking them apart like curious watches? -Claude Debussy1 Clichés and Questions A favourite of the anthologies and survey texts, Debussy’s second piano prelude, Voiles (‘sails’ or ‘veils’), has attained near-iconic status as the most characteristic single exemplar of his style. -

Impressionism in Selected Works for Flute an Honors Thesis

Impressionism in Selected Works for Flute An Honors Thesis (MUSPE 498) by Jennifer L. Zent Thesis Advisor Dr. JUlia Larson Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 1,1995 May 6,1995 (,..(,-- ¥ '-::) " 'T?'Qij '0 L~- C ~ lit,'! 1/_',- i} Abstract The following paper discusses how impressionism influenced composers at the turn of the twentieth century. as demonstrated by flute compositions of the period. The works discussed are: Fantasje. Op. 79 (1898) by Gabriel Faure; Piece en forme de Habanera (1907) by Maurice Ravel; Madrigal (1908) by Philippe Gaubert; Syrinx (1913) by Claude Debussy; Poem for Flute and Orchestra (1918) by Charles Griffes; Danse de la ch9yre (1919) by Arthur Honegger; and Sonata for Flute and Piano (1956) by Francis Poulenc. This creative project also involved a public recital of these works. for which program notes were prepared; a copy of the program and a recording of the recital are included. French music at the end of the nineteenth century featured several contrasting styles. One school, led by Cesar Franck and his student Vincent d'indy, emphasized the use of classical forms and regular thematic development, within a romantic harmonic framework. Another important movement was the French style, whose main composers were Camille Saint- Saens and his student Gabriel Faure. Their music was characterized by the classical ideas of order, balance, and restraint. "It was subtle, not dramatic, quiet, and full of nuances."1 But perhaps the most revolutionary ideas came from Claude Debussy and his new musical movement called impressionism. This style was influenced by a type of French art and poetry which captured impressions that a subject made, rather than strict representations. -

Multicultural Influences in Debussy's Piano Music

Multicultural Influences in Debussy’s Piano Music By © 2019 Tharach Wuthiwan Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Chair: Jack Winerock Scott McBride Smith Michael Kirkendoll Ketty Wong Jane Zhao Date Defended: 21 November 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Tharach Wuthiwan certifies that this is the approved version of the following doctoral document: Multicultural Influences in Debussy’s Piano Music Chair: Jack Winerock Date Approved: 21 November 2019 iii Abstract Debussy has been known for integrating different subjects into his music such as pictures, scenes of nature, poems, and elements from other cultures that leave the listener with the impression that Debussy tries to capture in his music. This paper focuses on multicultural influences on Debussy’s Estampes, a suite published in 1903 that contains references to three different cultures: Javanese, Spanish, and French cultures. The first piece, Pagodes, evokes the musical culture of the Javanese Gamelan of Indonesia, which Debussy first encountered in a performance he saw at the Paris Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair) in 1889. Debussy uses pentatonic, pedal-tone, and polyphonic texture to imitate the sound of the Javanese gamelan instruments. Besides Pagodes, Debussy uses similar techniques in Prelude from Pour Le Piano and Et la lune descend sur le temple qui fut from Images Book 2. La soirée dans Grenade evokes the musical character of Granada in Andalusia, Spain by using the habanera dance rhythm, melodies inspired by the Moorish heritage of Spain, and the rolled chords that imitate the strumming gesture of the Spanish guitar. -

A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS of the PIANO WORKS of DEBUSSY and RAVEL THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State T

AW& A STYLISTIC ANALYSIS OF THE PIANO WORKS OF DEBUSSY AND RAVEL THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State Teachers College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Elizabeth Rose Jameson, B. Yi. Denton, Texas May, 1942 98756 9?756 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES . , . , . v LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ..... vi Chapter I.INTRODUCTION .... ,*** . * The Birth of Modern French Music Problem Need for the Study Scope of Study Procedure Presentation II. THE LIFE AND WORKS OF CLAUDE DEBUSSY . 12 Life Works III. THE LIFE AND WORKS OF JOSEPH 1.AURICE RAVEL . -- - . , 27 Life Works IV. STYLISTIC ELEMENTS OF DEBUSSY'S LUSIC . .37 Rhythm Melody Harmony Modulation Form Tonality Cadences Dynamics Texture iii Page V. STYLISTIC ELEMENTS OF RAVEL'S llUS IC . 108 Rhythm melody Harmony Modulation Form Tonality Cadences Dyanmics Texture VI. A COMPARISON OF DEBUSSY AND RAVEL . 149 General Comparison Rhythm elody Harmony Modulation Form Tonality Cadences Dynamics Texture Idiomatic treatment VII. CONCLUSION . 0 . 167 APPENDIX . .. 0 . 0 . 0 . 171 BIBLIOGIRPHY . .* . 0 . .0 176 iv LIST OF TABLES Table Page I. Diversity of Ivetrical Scheme Found in Six Different Com- positions of Debussy, Preludes, Book II, ------.. 39 2. Types of Triplets Found in Piano Compositions of Debussy and Places Where They Are Found. 56 3. Analysis of Form of Debussy's a .0 Piano Works . ...& . 0 . 97 4. Compositions of Debussy, the Number of Measures Marked Piano, and the Number of Measures Marked Forte . 0 . 0 . 106 5. Form Analysis of Ravel's Piano Works . .*.. 0 0 0 . -

Edexcel AS and a Level Aos5: Debussy's Estampes

KSKS55 Edexcel AS and A level AoS5: Debussy’s Estampes Simon Rushby is assistant head at by Simon Rushby Reigate Grammar School in Surrey, and was a director of music for 15 years, and a TEACHING THE SET WORKS principal examiner for A level music. He Students are studying Debussy’s Estampes and the other set works in preparation for a summer Edexcel is author of various exam paper either at AS or A Level. A previous Music Teacher resource (January 2017) has already given an books, articles and resources on music overview of the appraising paper, including which questions will be asked in the exam papers; details of what education. He is an students need to learn in terms of musical elements, context and language; and advice on how to break down ABRSM and A level the areas of study. Some specific sample questions are also suggested at the end of this article. examiner, and a songwriter and composer. A suggested strategy for approaching each set work is also set out in this article, and it covers not only how to plan the study of works such as Debussy’s Estampes, but also how to incorporate wider listening into the scheme of work. In section B of both the AS and A level papers there will be a question that requires students to be able to draw links from their set works to a piece of unfamiliar music, so it is essential to include practice at picking out features from music less familiar to them as part of the set work study. -

MUSIC RESOURCE PACK Music Resource Pack

DEBUSSY MUSIC RESOURCE PACK Music Resource Pack BONJOUR! Welcome to your free music resource pack focused on the life and works of Claude Debussy! We hope you enjoy celebrating 100 years of Debussy’s music with us by engaging with the included material, in particular ‘Children’s Corner’. A variety of information is available with the aim to inspire creative and educational teaching around the theme of Debussy and the wider reaches of his music. As well as music, there are many interesting links to other subjects, projects and ideas. Subjects mentioned include Art & Design, Creative Writing, History, Science and Geography. Ideas are suggested as a starting point and can be elaborated on or transformed to suit your class as appropriate - be guided by your creativity! Debussy: The Man Behind the Music Claude Debussy (Klod De-Boo-see) was born in France in 1862. He was the oldest of five children, his father owned a shop and his mother was a seamstress. When he was ten years old he started studying at the Paris Conservatoire, a very famous music school. He studied piano and composition and he liked to experiment with music, not always sticking to what many people thought were the rules. Many things inspired Debussy throughout his life and found their way into his music. These include nature, Japanese art, childhood, the sounds of Jazz and Gamelan music. We’ll explore some of them in this pack. Children’s Corner Debussy was married twice and had one child, called Claude Emma, and she was the inspiration for his set of six pieces for solo piano, Children’s Corner. -

Debussy La Flûte De Pan the Confluence of Poem and Music

A Symbolist Melodrama: The Confluence of Poem and Music in Debussy’s La Flûte de Pan Laurel Astrid Ewell Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts John Weigand, D.M.A., Chair John Edward Crotty, Ph.D., Research Advisor Virginia Thompson, D.M.A. Joyce Catalfano, M.M. Alison Helm-Snyder, M.F.A. Department of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2004 Keywords: Claude Debussy, Symbolist Poetry, Music Analysis, Melodrama, Syrinx, La Flûte de Pan Copyright 2004 Laurel Astrid Ewell Abstract A Symbolist Melodrama: The Confluence of Poem and Music in Debussy’s La Flûte de Pan Laurel Astrid Ewell Composed by Debussy in 1913, as incidental music for Psyché, a dramatic poem by French symbolist poet and playwright Gabriel Mourey, the work for solo flute known today as Syrinx, has since become a standard of the solo flute repertoire. Anders Ljungar- Chapelon, editor of a new edition based on a recently recovered period manuscript, has challenged traditional conceptions of the work’s compositional context. Debussy’s original title for Syrinx was La Flûte de Pan and appeared as a musical component of a mélodrame within the play, just prior to the death of Pan. The recovery of a probable primary source manuscript plus information gathered from Debussy’s correspondence invites a new look at this piece, taking into consideration connections between Mourey’s Symbolist poetry and Debussy’s compositional procedures. The analysis of the poem and music reveals a process which represents or analogizes the symbolist associations and techniques of the concurrent text thereby creating a convergence between poem and music. -

TONAL AMBIGUITY in DEBUSSY's PIANO WORKS by RIKA UCHIDA A

TONAL AMBIGUITY IN DEBUSSY'S PIANO WORKS by RIKA UCHIDA A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and the Graduate S�hool of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 1990 111 An Abstract of the Thesis of Rika Uchida for the degree of Master of Arts in the School of Music to be taken December 1990 Title: TONAL AMBIGUITY IN DEBUSSY'S PIANO WORKS Approved: Dr. Harold Owen Claude Debussy lived at a special point in the history of Music: .the turning point from the nineteenth to the twentieth century. As many of his contemporaries did, he tried to free himself from all the limitations of functional harmony and tonality. Instead of using. extreme chromaticism, he employed medieval church modes, whole-tone and pentatonic scales, planing, stepwise root movement, and harmonies built on intervals other than the third. All these factors tend to reject local tonal hierarchies and help to achieve tonal ambiguity. This study traces the gradual shift from clarity of tonality towards tonal ambiguity in Debussy's piano music and examines a variety of compositional techniques that he applied to achieve tonal ambiguity in each work. iv VITA NAME OF AUTHOR: Rika Uchida PLACE OF BIRTH: Tokyo, Japan GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SCHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon Tsuda College DEGREE AWARDED: Master of Arts, 1990, University of Oregon Bachelor of Arts, 1981, Tsuda College AREAS OF SPECIAL INTEREST: French Impressionistic Music Counterpoint and Fugue PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: School of Music Assistantship, University of Oregon, Eugene, 1989-1990 Graduate Teaching Fellow, School of Music, University of Oregon, Eugene, 1990 V ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express sincere appreciation to Dr.