Les Chansons De Bilitis: a Symbiotic Collaboration Between Two Artists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary

The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas R. Bell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2015 Reading Committee: Dr. Sabine Wilke, Chair Dr. Richard Block Dr. Eric Ames Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Germanics ©Copyright 2015 Thomas R. Bell University of Washington Abstract The Postsecular Traces of Transcendence in Contemporary German Literature Thomas Richard Bell Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Sabine Wilke Germanics This dissertation focuses on texts written by four contemporary, German-speaking authors: W. G. Sebald’s Die Ringe des Saturn and Schwindel. Gefühle, Daniel Kehlmann’s Die Vermessung der Welt, Sybille Lewitscharoff’s Blumenberg, and Peter Handke’s Der Große Fall. The project explores how the texts represent forms of religion in an increasingly secular society. Religious themes, while never disappearing, have recently been reactivated in the context of the secular age. This current societal milieu of secularism, as delineated by Charles Taylor, provides the framework in which these fictional texts, when manifesting religious intuitions, offer a postsecular perspective that serves as an alternative mode of thought. The project asks how contemporary literature, as it participates in the construction of secular dialogue, generates moments of religiously coded transcendence. What textual and narrative techniques serve to convey new ways of perceiving and experiencing transcendence within the immanence felt and emphasized in the modern moment? While observing what the textual strategies do to evoke religious presence, the dissertation also looks at the type of religious discourse produced within the texts. The project begins with the assertion that a historically antecedent model of religion – namely, Friedrich Schleiermacher’s – which is never mentioned explicitly but implicitly present throughout, informs the style of religious discourse. -

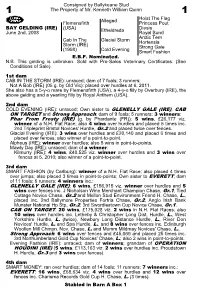

OPERATION HOUDINI (IRE) (5 Wins, £113,163 Viz

Consigned by Ballykeane Stud 1 The Property of Mr. Kenneth William Quinn 1 Hoist The Flag Alleged Flemensfirth Princess Pout BAY GELDING (IRE) (USA) Diesis June 2nd, 2008 Etheldreda Royal Bund Arctic Tern Cab In The Glacial Storm Hortensia Storm (IRE) Strong Gale (1998) Cold Evening Smart Fashion E.B.F. Nominated. N.B. This gelding is unbroken. Sold with Pre-Sales Veterinary Certificates. (See Conditions of Sale). 1st dam CAB IN THE STORM (IRE): unraced; dam of 7 foals; 3 runners: Not A Bob (IRE) (05 g. by Old Vic): placed over hurdles at 6, 2011. She also has a 5-y-o mare by Flemensfirth (USA), a 4-y-o filly by Overbury (IRE), the above gelding and a yearling filly by Royal Anthem (USA). 2nd dam COLD EVENING (IRE): unraced; Own sister to GLENELLY GALE (IRE), CAB ON TARGET and Strong Approach; dam of 9 foals; 5 runners; 3 winners: Phar From Frosty (IRE) (g. by Phardante (FR)): 5 wins, £26,177 viz. winner of a N.H. Flat Race; also 4 wins over hurdles and placed 5 times inc. 2nd Tripleprint Bristol Novices' Hurdle, Gr.2 and placed twice over fences. Glacial Evening (IRE): 3 wins over hurdles and £20,140 and placed 6 times and placed over fences; also winner of a point-to-point. Alpheus (IRE): winner over hurdles; also 5 wins in point-to-points. Mawly Day (IRE): unraced; dam of a winner: Kilmurry (IRE): 4 wins, £40,525 viz. winner over hurdles and 3 wins over fences at 5, 2010; also winner of a point-to-point. -

Claude Debussy in 2018: a Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies

19-23/03/18 CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN 2018: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION ABSTRACTS AND BIOGRAPHIES Claude Debussy in 2018: A Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies I. Debussy Perspectives, 1918-2018 RNCM, Manchester Monday, 19 March Paper session A: Debussy’s Style in History, Conference Room, 2.00-5.00 Chair: Marianne Wheeldon 2.00-2.30 – Mark DeVoto (Tufts University), ‘Debussy’s Evolving Style and Technique in Rodrigue et Chimène’ Claude Debussy’s Rodrigue et Chimène, on which he worked for two years in 1891-92 before abandoning it, is the most extensive of more than a dozen unfinished operatic projects that occupied him during his lifetime. It can also be regarded as a Franco-Wagnerian opera in the same tradition as Lalo’s Le Roi d’Ys (1888), Chabrier’s Gwendoline (1886), d’Indy’s Fervaal (1895), and Chausson’s Le Roi Arthus (1895), representing part of the absorption of the younger generation of French composers in Wagner’s operatic ideals, harmonic idiom, and quasi-medieval myth; yet this kinship, more than the weaknesses of Catulle Mendès’s libretto, may be the real reason that Debussy cast Rodrigue aside, recognising it as a necessary exercise to be discarded before he could find his own operatic voice (as he soon did in Pelléas et Mélisande, beginning in 1893). The sketches for Rodrigue et Chimène shed considerable light on the evolution of Debussy’s technique in dramatic construction as well as his idiosyncratic approach to tonal form. Even in its unfinished state — comprising three out of a projected four acts — the opera represents an impressive transitional stage between the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra (1890) and the full emergence of his genius, beginning with the String Quartet (1893) and the Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune (1894). -

Belle Epoque` SUPER AUDIO CD

SUPER AUDIO CD ` FRENCH Belle MUSIC Epoque FOR WIND Orsino Ensemble with Pavel Kolesnikov piano André Caplet, c. 1898 Royal College of Music / ArenaPAL Belle Époque: French Music for Wind Albert Roussel (1869 – 1937) 1 Divertissement, Op. 6 (1906) 6:59 for Flute, Oboe, Clarinet, Bassoon, Horn, and Piano À la Société Moderne d’Instruments à vent Animé – En retenant – Un peu moins animé – En animant – Animé (Premier mouvement) – Un peu moins animé – En retenant progressivement – Lent – Animez un peu – Lent – En animant peu à peu – Animé – Un peu moins animé – Lent – Animé (Premier mouvement) – Moins vite et en retenant – Très modéré 3 Achille-Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918) 2 Petite Pièce (1910) 1:29 Morceau à déchiffrer pour le concours de clarinette de 1910 (Piece for sight-reading at the clarinet competition of 1910) for Clarinet and Piano Modéré et doucement rythmé – Un peu retenu 3 Première Rhapsodie (1909 – 10) 8:20 for Clarinet and Piano À P. Mimart Rêveusement lent – Poco mosso – Scherzando. Le double plus vite – En retenant peu à peu – Tempo I – Le double plus vite – Un peu retenu – Modérément animé (Scherzando) – Un peu retenu – Plus retenu – A tempo (Modérément animé) – Même mouvement – Même mouvement – Scherzando – Tempo I – Animez et augmentez, peu à peu – Animez et augmentez toujours – Animé – Plus animé (Scherzando) – Un peu retenu – Au mouvement 4 Camille Saint-Saëns (1835 – 1921) 4 Romance, Op. 36 (1874) 3:41 in F major • in F-Dur • en fa majeur Fourth Movement from Suite for Cello and Piano, Op. 16 (1862) Arranged by the Composer for Horn and Piano À Monsieur J. -

CLAUDE DEBUSSY in 2018: a CENTENARY CELEBRATION PROGRAMME Monday 19 - Friday 23 March 2018 CLAUDE DEBUSSY in 2018: a CENTENARY CELEBRATION

19-23/03/18 CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN 2018: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION PROGRAMME Monday 19 - Friday 23 March 2018 CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN 2018: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION Patron Her Majesty The Queen President Sir John Tomlinson CBE Principal Professor Linda Merrick Chairman Nick Prettejohn To enhance everyone’s experience of this event please try to stifle coughs and sneezes, avoid unwrapping sweets during the performance and switch off mobile phones, pagers and digital alarms. Please do not take photographs or video in 0161 907 5555 X the venue. Latecomers will not be admitted until a suitable break in the 1 2 3 4 5 6 programme, or at the first interval, whichever is the more appropriate. 7 8 9 * 0 # < @ > The RNCM reserves the right to change artists and/or programmes as necessary. The RNCM reserves the right of admission. 0161 907 5555 X 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 * 0 # < @ > Welcome It gives me great pleasure to welcome you to Claude Debussy in 2018: a Centenary Celebration, marking the 100th anniversary of the death of Claude Debussy on 25 March 1918. Divided into two conferences, ‘Debussy Perspectives’ at the RNCM and ‘Debussy’s Late work and the Musical Worlds of Wartime Paris’ at the University of Glasgow, this significant five-day event brings together world experts and emerging scholars to reflect critically on the current state of Debussy research of all kinds. With guest speakers from 13 countries, including Brazil, China and the USA, we explore Debussy’s editions and sketches, critical and interpretative approaches, textual and cultural-historical analysis, and his legacy in performance, recording, composition and arrangement. -

Basinskimyersvap B Urns V Ogel S Ieczkowski K a M I N S K I Haukejorgenson B Aus B Rox L Owinger I Ijima D Enrow Taylorsmithtynes S Ikkema Dusie

BASINSKIMYERSVAP B URNS V OGEL S IECZKOWSKI K A M I N S K I HAUKEJORGENSON B AUS B ROX L OWINGER I IJIMA D ENROW TAYLORSMITHTYNES S IKKEMA DUSIE Cover art by Michael Basinski, 2012 ISSUE 13, VOL 4 NO 1 ISSN 1661-6685 For more information about DUSIE PRESS BOOKS and DUSIE the online literary journal, please visit: www.dusie.org/, or contact the editor at [email protected]. DUSIE ZÜRICH 2012 CONTRIBUTORS 6 Introduction 9 Michael Basinski 13 Danielle Vogel 17 Megan Burns 20 Sarah Vap 23 Gina Myers 29 Brenda Sieczkowski 34 Megan Kaminski 38 Nathan Hauke 44 Kirsten Jorgenson 48 Eric Baus 50 Robin Brox 55 Aaron Lowinger 61 Brenda Iijima 64 Jennifer Denrow 69 Shelly Taylor 74 Abraham Smith 79 Jen Tynes 87 Michael Sikkema 93 Contributor Bios 96 DUSIE NEWS In a selection from Lew Welch's Collected Poems, we get a crystal clear look at Radical Vernacular Poetics. I don't have the tech savvy to drum up the lovely zen calligraphy circle that heads the page but the text reads: Step out onto the Planet. Draw a circle a hundred feet round. Inside the circle are 300 things nobody understands, and maybe nobody's ever really seen. How many can you find? Between them, the poets in this issue found all 300 and then some. They found their 300 things on the bus, in hypnosis, on a social work call, listening to Elizabeth Cotton, thinking about Nicki Minaj, contemplating the edges of the mother body, finding ways to let the swamp gas speak, talking straight to the elephants in the room. -

Benesh Movement Notation Score Catalogue: an International Listing of Benesh Movement Notation Scores of Professional Dance Works, Recorded 1955-1998 Ed

Extraction from: Benesh Movement Notation Score Catalogue: An International listing of Benesh Movement Notation scores of professional dance works, recorded 1955-1998 Ed. Inman, T. © Royal Academy of Dance, London, 1998 All scores listed are unpublished and are not necessarily available for general use. The Institue has endeavoured to gather information of all existing notated choreographic works, however, the omission of certain titles does not necessarily mean that no notation of the work exists. Score Lodgement: Numbered scores – a copy is held in the Philip Richardson Library for public viewing. SK: Safe Keeping – not available for public vewing. Educational Use: Scores available for educational use. Choreographer Work Composer Notator Score Educational Lodgement Use ACHCAR, D. Nutcracker, The (excerpts) Tchaikovsky, P. I. Schroeder, C. - ACHCAR, D. / ASHTON, F. Floresta Amazônica Villa-Lobos, H. Parker, M. - AILEY, A. Myth (excerpts) Stravinsky, I. Suprun, I. - AILEY, A. River, The Ellington, D. Lindström, E. 523 AILEY, A. Night Creature Ellington, D. - AILEY, A. Night Creature (2nd & 3rd sections) Ellington, D. Suprun, I. - AITKEN, G. Naila Delibes, L. Marwood, J. - ALSTON, R. Apollo Distraught Osborne, N. Cunliffe, L. - EU ALSTON, R. Cat’s Eyes Sawer, D. Reeder, K. - ALSTON, R. Chicago Brass Hindemith, P. Braban, M. 374 EU ALSTON, R. Cinema Satie, E. Macourt, M. - ALSTON, R. Cutter Gowans, J.-M. Sandles, J. 481 ALSTON, R. Dangerous Liaisons Waters, S. Dyer, A. 430 EU ALSTON, R. Dealing with Shadows Mozart, W. A. Macourt, M. - ALSTON, R. Dutiful Ducks Armirkhanian, C. Tierney, P. 478 EU ALSTON, R. Hymnos Maxwell Davies, P. - ALSTON, R. Java The Ink Spots Dyer, A. -

The Choral Cycle

THE CHORAL CYCLE: A CONDUCTOR‟S GUIDE TO FOUR REPRESENTATIVE WORKS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY RUSSELL THORNGATE DISSERTATION ADVISORS: DR. LINDA POHLY AND DR. ANDREW CROW BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2011 Contents Permissions ……………………………………………………………………… v Introduction What Is a Choral Cycle? .............................................................................1 Statement of Purpose and Need for the Study ............................................4 Definition of Terms and Methodology .......................................................6 Chapter 1: Choral Cycles in Historical Context The Emergence of the Choral Cycle .......................................................... 8 Early Predecessors of the Choral Cycle ....................................................11 Romantic-Era Song Cycles ..................................................................... 15 Choral-like Genres: Vocal Chamber Music ..............................................17 Sacred Cyclical Choral Works of the Romantic Era ................................20 Secular Cyclical Choral Works of the Romantic Era .............................. 22 The Choral Cycle in the Twentieth Century ............................................ 25 Early Twentieth-Century American Cycles ............................................. 25 Twentieth-Century European Cycles ....................................................... 27 Later Twentieth-Century American -

Air Supremacy in US Air Force History, Theory, and Doctrine

A HOUSE BUILT ON SAND: Air Supremacy in US Air Force History, Theory, and Doctrine E. Taylor Francis Major, USAF Air University James B. Hecker, Lieutenant General, Commander and President LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education Brad M. Sullivan, Major General, Commander AIR UNIVERSITY LEMAY CENTER FOR DOCTRINE DEVELOPMENT AND EDUCATION A House Built on Sand: Air Supremacy in US Air Force History, Theory, and Doctrine E. Taylor Francis, Major, USAF Lemay Paper No. 6 Air University Press Muir S. Fairchild Research Information Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama Air University Commander and President Accepted by Air University Press May 2019 and published April 2020. Lt Gen James B. Hecker Commandant and Dean, LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education Maj Gen Brad Sullivan Director, Air University Press Lt Col Darin M. Gregg Project Editor Dr. Stephanie Havron Rollins Illustrator Daniel Armstrong Print Specialist Megan N. Hoehn Distribution Diane Clark Disclaimer Air University Press Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied 600 Chennault Circle, Building 1405 within are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily repre- Maxwell AFB, AL 36112-6010 sent the official policy or position of the organizations with which https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/AUPress/ they are associated or the views of the Air University Press, LeMay Center, Air University, United States Air Force, Department of Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AirUnivPress Defense, or any other US government agency. This publication is cleared for public release and unlimited distribution. and This LeMay Paper and others in the series are available electronically Twitter: https://twitter.com/aupress at the AU Press website: https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/AUPress/ LeMay-Papers/. -

Stylistic Influences and Musical Quotations in Claude Debussy's Children's Corner and La Boîte A

EVOCATIONS FROM CHILDHOOD: STYLISTIC INFLUENCES AND MUSICAL QUOTATIONS IN CLAUDE DEBUSSY’S CHILDREN’S CORNER AND LA BOÎTE À JOUJOUX Hsing-Yin Ko, M.B., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2011 APPROVED: Vladimir Viardo, Major Professor Elvia Puccinelli, Minor Professor Frank Heidlberger, Committee Member Jesse Eschbach, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Lynn Eustis, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of College of Music James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Ko, Hsing-Yin, Evocations from Childhood: Stylistic Influences and Musical Quotations in Claude Debussy’s Children’s Corner and La Boîte à Joujoux. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2011, 44 pp., 33 musical examples, bibliographies, 43 titles. Claude Debussy is considered one of the most influential figures of the late 19th century and early 20th centuries. Among the various works that he wrote for the piano, Children’s Corner and La Boîte à joujoux distinguish themselves as being evocative of childhood. However, compared to more substantial works like Pelléas et Mélisande or La Mer, his children’s piano music has been underrated and seldom performed. Children’s Corner and La Boîte à joujoux were influenced by a series of eclectic sources, including jazz, novel “views” from Russian composers, and traditional musical elements such as folk songs and Eastern music. The study examines several stylistic parallels found in these two pieces and is followed by a discussion of Debussy’s use of musical quotations and allusions, important elements used by the composer to achieve what could be dubbed as a unique “children’s wonderland.” Copyright 2011 by Hsing-Yin Ko ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES ............................................................................................... -

Audition Repertoire, Please Contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 Or by E-Mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS for VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS

1 AUDITION GUIDE AND SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS AUDITION REQUIREMENTS AND GUIDE . 3 SUGGESTED REPERTOIRE Piano/Keyboard . 5 STRINGS Violin . 6 Viola . 7 Cello . 8 String Bass . 10 WOODWINDS Flute . 12 Oboe . 13 Bassoon . 14 Clarinet . 15 Alto Saxophone . 16 Tenor Saxophone . 17 BRASS Trumpet/Cornet . 18 Horn . 19 Trombone . 20 Euphonium/Baritone . 21 Tuba/Sousaphone . 21 PERCUSSION Drum Set . 23 Xylophone-Marimba-Vibraphone . 23 Snare Drum . 24 Timpani . 26 Multiple Percussion . 26 Multi-Tenor . 27 VOICE Female Voice . 28 Male Voice . 30 Guitar . 33 2 3 The repertoire lists which follow should be used as a guide when choosing audition selections. There are no required selections. However, the following lists illustrate Students wishing to pursue the Instrumental or Vocal Performancethe genres, styles, degrees and difficulty are strongly levels encouraged of music that to adhereis typically closely expected to the of repertoire a student suggestionspursuing a music in this degree. list. Students pursuing the Sound Engineering, Music Business and Music Composition degrees may select repertoire that is slightly less demanding, but should select compositions that are similar to the selections on this list. If you have [email protected] questions about. this list or whether or not a specific piece is acceptable audition repertoire, please contact the Music Department at 812.941.2655 or by e-mail at AUDITION REQUIREMENTS FOR VARIOUS DEGREE CONCENTRATIONS All students applying for admission to the Music Department must complete a performance audition regardless of the student’s intended degree concentration. However, the performance standards and appropriaterequirements audition do vary repertoire.depending on which concentration the student intends to pursue. -

Download This PDF File

JOURNAL OF RESEARCH ONLINE MusicA JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC COUNCIL OF AUSTRALIA ‘Jangling in symmetrical sounds’: Maurice Ravel as storyteller and poet aurice Ravel’s perception of language was defined by his métier. He thought EMILY KILPATRICK about words as a composer, understanding them in terms of their rhythms and Mresonances in the ear. He could recognise the swing of a perfectly balanced phrase, the slight changes of inflection that affect sense and emphasis, and the rhythm ■ Elder Conservatorium and melody inherent in spoken language. Ravel’s letters, his critical writings, his vocal of Music music and, most strikingly, his poetry, reveal his undeniable talent for literary expression. University of Adelaide He had a pronounced taste for onomatopoeia and seemed to delight in the dextrous South Australia 5005 juggling of rhymes and rhythms. As this paper explores, these qualities are particularly Australia apparent in the little song Noël des jouets (1905) and the choral Trois chansons pour chœur mixte sans accompagnement (1915) for which Ravel wrote his own texts, together Email: emily.kilpatrick with his collaboration with Colette on the opera L’Enfant et les sortilèges (1925). @adelaide.edu.au The common thread of fantasy and fairytale that runs through these three works suggests that through his expressive use of language Ravel was deliberately aligning his music with the traditions of storytelling, a genre defined by the sounds of the spoken word. Fairytales usually employ elegant and beautiful formal language that is direct, expressive and naturally musical, as typified in the memorable phrases‘Once upon a time…’ and ‘… happily ever after’.