Multicultural Influences in Debussy's Piano Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1J131J Alexander Boggs Ryan,, Jr., B

omit THE PIANO STYLE OF CLAUDE DEBUSSY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC by 1J131J Alexander Boggs Ryan,, Jr., B. M. Longview, Texas June, 1951 19139 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . , . iv Chapter I. THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PIANO AS AN INFLUENCE ON STYLE . , . , . , . , . , . ., , , 1 II. DEBUSSY'S GENERAL MUSICAL STYLE . IS Melody Harmony Non--Harmonic Tones Rhythm III. INFLUENCES ON DEBUSSY'S PIANO WORKS . 56 APPENDIX (CHRONOLOGICAL LIST 0F DEBUSSY'S COMPLETE WORKS FOR PIANO) . , , 9 9 0 , 0 , 9 , , 9 ,9 71 BIBLIOGRAPHY *0 * * 0* '. * 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 .9 76 111 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Range of the piano . 2 2. Range of Beethoven Sonata 10, No.*. 3 . 9 3. Range of Beethoven Sonata .2. 111 . , . 9 4. Beethoven PR. 110, first movement, mm, 25-27 . 10 5. Chopin Nocturne in D Flat,._. 27,, No. 2 . 11 6. Field Nocturne No. 5 in B FlatMjodr . #.. 12 7. Chopin Nocturne,-Pp. 32, No. 2 . 13 8. Chopin Andante Spianato,,O . 22, mm. 41-42 . 13 9. An example of "thick technique" as found in the Chopin Fantaisie in F minor, 2. 49, mm. 99-101 -0 --9 -- 0 - 0 - .0 .. 0 . 15 10. Debussy Clair de lune, mm. 1-4. 23 11. Chopin Berceuse, OR. 51, mm. 1-4 . 24 12., Debussy La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune, mm. 32-34 . 25 13, Wagner Tristan und Isolde, Prelude to Act I, . -

Liner Notes (PDF)

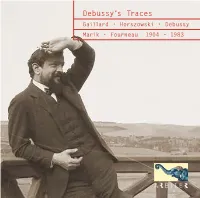

Debussy’s Traces Gaillard • Horszowski • Debussy Marik • Fourneau 1904 – 1983 Debussy’s Traces: Marius François Gaillard, CD II: Marik, Ranck, Horszowski, Garden, Debussy, Fourneau 1. Preludes, Book I: La Cathédrale engloutie 4:55 2. Preludes, Book I: Minstrels 1:57 CD I: 3. Preludes, Book II: La puerta del Vino 3:10 Marius-François Gaillard: 4. Preludes, Book II: Général Lavine 2:13 1. Valse Romantique 3:30 5. Preludes, Book II: Ondine 3:03 2. Arabesque no. 1 3:00 6. Preludes, Book II Homage à S. Pickwick, Esq. 2:39 3. Arabesque no. 2 2:34 7. Estampes: Pagodes 3:56 4. Ballade 5:20 8. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 4:49 5. Mazurka 2:52 Irén Marik: 6. Suite Bergamasque: Prélude 3:31 9. Preludes, Book I: Des pas sur la neige 3:10 7. Suite Bergamasque: Menuet 4:53 10. Preludes, Book II: Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses 8. Suite Bergamasque: Clair de lune 4:07 3:03 9. Pour le Piano: Prélude 3:47 Mieczysław Horszowski: Childrens Corner Suite: 10. Pour le Piano: Sarabande 5:08 11. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:48 11. Pour le Piano: Toccata 3:53 12. Jimbo’s lullaby 3:16 12. Masques 5:15 13 Serenade of the Doll 2:52 13. Estampes: Pagodes 3:49 14. The snow is dancing 3:01 14. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 3:53 15. The little Shepherd 2:16 15. Estampes: Jardins sous la pluie 3:27 16. Golliwog’s Cake walk 3:07 16. Images, Book I: Reflets dans l’eau 4:01 Mary Garden & Claude Debussy: Ariettes oubliées: 17. -

1) Aspects of the Musical Careers of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel

Edvard Grieg, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. Biographical issues and a comparison of their string quartets Juliette L. Appold I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects II. Connections between Grieg, Debussy and Ravel III. Observations on their string quartets I. Grieg, Debussy and Ravel – Biographical aspects Looking at the biographies of Grieg, Debussy and Ravel makes us realise, that there are few, yet some similarities in the way their career as composers were shaped. In my introductory paragraph I will point out some of these aspects. The three composers received their first musical training in their childhood, between the age of six (Grieg) and nine (Debussy) (Ravel was seven). They all entered the conservatory in their early teenage years (Debussy was 10, Ravel 14, Grieg 15 years old) and they all had more or less difficult experiences when they seriously thought about a musical career. In Grieg’s case it happened twice in his life. Once, when a school teacher ridiculed one of his first compositions in front of his class-mates.i The second time was less drastic but more subtle during his studies at the Leipzig Conservatory until 1862.ii Grieg had despised the pedagogical methods of some teachers and felt that he did not improve in his composition studies or even learn anything.iii On the other hand he was successful in his piano-classes with Carl Ferdinand Wenzel and Ignaz Moscheles, who had put a strong emphasis on the expression in his playing.iv Debussy and Ravel both were also very good piano players and originally wanted to become professional pianists. -

Harmonic Structures and Their Relation to Temporal Proportion in Two String Quartets of Béla Bartók

Harmonic structures and their relation to temporal proportion in two string quartets of Béla Bartók Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kissler, John Michael Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 22:08:34 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/557861 HARMONIC STRUCTURES AND THEIR RELATION TO TEMPORAL PROPORTION IN TWO STRING QUARTETS OF BELA BARTOK by John Michael Kissler A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of . MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 8 1 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript.in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

24. Debussy Pour Le Piano: Sarabande (For Unit 3: Developing Musical Understanding)

24. Debussy Pour le piano: Sarabande (For Unit 3: Developing Musical Understanding) Introduction and Performance circumstances Debussy probably decided to compose a Sarabande partly because he knew Erik Satie’s three sarabandes of 1887, with their similarly sensuous harmony. There are no grounds for referring to Debussy’s Sarabande as ‘impressionist’, even though the piece is very similar in date to his Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. The term ‘neoclassical’ may be more suitable, although we do not hear the post-World War I type of ‘wrong-note’ neoclassicism of, for example, Stravinsky’s Pulcinella. In public performance Debussy’s Sarabande is most likely to be heard as part of a piano recital, along with the two other movements which flank it (Prélude and Toccata) from Pour le piano. Incidentally the suite was published in 1901, but the Sarabande (in a slightly different version to the one we know) dates back to 1894. Performing Forces and their Handling Sarabande, for solo piano, does not depend for its effect on any virtuosity or display. Marguerite Long, a pupil of Debussy, noted that the composer ‘himself played [the piece] as no one [else] could ever have done, with those marvellous successions of chords sustained by his intense legato’. A wide range is involved, from (several) very low C sharps to E just over five octaves higher; there are no extremely high notes. Some left-hand chords extend to well over an octave and have to be spread. Texture The texture is almost entirely homophonic, with much parallelism, and is often extremely sonorous on account of the many chords with six or more notes. -

Andrián Pertout

Andrián Pertout Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition Volume 1 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Produced on acid-free paper Faculty of Music The University of Melbourne March, 2007 Abstract Three Microtonal Compositions: The Utilization of Tuning Systems in Modern Composition encompasses the work undertaken by Lou Harrison (widely regarded as one of America’s most influential and original composers) with regards to just intonation, and tuning and scale systems from around the globe – also taking into account the influential work of Alain Daniélou (Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales), Harry Partch (Genesis of a Music), and Ben Johnston (Scalar Order as a Compositional Resource). The essence of the project being to reveal the compositional applications of a selection of Persian, Indonesian, and Japanese musical scales utilized in three very distinct systems: theory versus performance practice and the ‘Scale of Fifths’, or cyclic division of the octave; the equally-tempered division of the octave; and the ‘Scale of Proportions’, or harmonic division of the octave championed by Harrison, among others – outlining their theoretical and aesthetic rationale, as well as their historical foundations. The project begins with the creation of three new microtonal works tailored to address some of the compositional issues of each system, and ending with an articulated exposition; obtained via the investigation of written sources, disclosure -

Claude Debussy in 2018: a Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies

19-23/03/18 CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN 2018: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION ABSTRACTS AND BIOGRAPHIES Claude Debussy in 2018: A Centenary Celebration Abstracts and Biographies I. Debussy Perspectives, 1918-2018 RNCM, Manchester Monday, 19 March Paper session A: Debussy’s Style in History, Conference Room, 2.00-5.00 Chair: Marianne Wheeldon 2.00-2.30 – Mark DeVoto (Tufts University), ‘Debussy’s Evolving Style and Technique in Rodrigue et Chimène’ Claude Debussy’s Rodrigue et Chimène, on which he worked for two years in 1891-92 before abandoning it, is the most extensive of more than a dozen unfinished operatic projects that occupied him during his lifetime. It can also be regarded as a Franco-Wagnerian opera in the same tradition as Lalo’s Le Roi d’Ys (1888), Chabrier’s Gwendoline (1886), d’Indy’s Fervaal (1895), and Chausson’s Le Roi Arthus (1895), representing part of the absorption of the younger generation of French composers in Wagner’s operatic ideals, harmonic idiom, and quasi-medieval myth; yet this kinship, more than the weaknesses of Catulle Mendès’s libretto, may be the real reason that Debussy cast Rodrigue aside, recognising it as a necessary exercise to be discarded before he could find his own operatic voice (as he soon did in Pelléas et Mélisande, beginning in 1893). The sketches for Rodrigue et Chimène shed considerable light on the evolution of Debussy’s technique in dramatic construction as well as his idiosyncratic approach to tonal form. Even in its unfinished state — comprising three out of a projected four acts — the opera represents an impressive transitional stage between the Fantaisie for piano and orchestra (1890) and the full emergence of his genius, beginning with the String Quartet (1893) and the Prélude à l’Après-midi d’un faune (1894). -

Claude Debussy Orchestral Works Dirk Altmann · Daniel Gauthier Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart Des SWR · Heinz Holliger 02 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862 – 1918) 03

Claude Debussy Orchestral Works Dirk Altmann · Daniel Gauthier Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart des SWR · Heinz Holliger 02 CLAUDE DEBUSSY (1862 – 1918) 03 1 Première Rapsodie pour orchestre 7 Prélude à L’après-midi d’un faune [11:35] Diese wesensmäßige Fertigkeit hatte schon in den Chemie“, an der er sich selbst immer neu ergötzen avec clarinette principale [08:15] flûte solo: Tatjana Ruhland frühen Neunzigern die Bedenken des Dichters konnte, und die aus sich selbst erwachsenden For- Stéphane Mallarmé zerstreut, der zunächst von men in Regelwerke zu zwängen, sich im Geflecht Images pour orchestre 8 Rapsodie pour Debussys Ansinnen, die Ekloge vom Après-midi des Gefundenen, bereits „Gehabten“ zu verhed- Deutsch 2 Rondes de Printemps [08:29] orchestre et saxophone [09:45] d’un faune mit Musik zu umgeben, nicht begeis- dern. Vielleicht wurde daher auch nur das Prélude 3 Gigues [08:38] tert war. Er fürchtete eine bloße „Verdopplung“ zum „Faun“ vollendet, während das Interlude und Iberia [19:48] TOTAL TIME [67:04] seiner musikalisch-erotischen Alexandriner, sah die abschließende Paraphrase nie über die Idee 4 I. Par les rues et par les chemins [07:09] sich aber, kaum dass er das Resultat zu hören be- hinausgelangten. Es war schon alles gesagt. 5 II. Les parfums de la nuit [08:10] 1 Dirk Altmann Klarinette | clarinet kam, ebenso bezwungen wie die Besucher der 6 III. Le matin d'un jour de fête [04:28] 8 Daniel Gauthier Saxophon | saxophone Société Nationale, die am 22. Dezember 1894 die Wer weiß, ob nicht aus just diesem Grunde auch Uraufführung des Prélude „zum Nachmittag eines die Rapsodie arabe im Sande verlief, die sich der Fauns“ miterleben durften. -

Download Program Notes

Notes on the Program By James M. Keller, Program Annotator, The Leni and Peter May Chair Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun) Nocturnes Claude Debussy laude Debussy achieved his musical produced. This work is too exquisite, alas! It Cmaturity in the final decade of the 19th is too exquisite.” century, a magical moment in France when partisans of the visual arts fully embraced the gentle luster of Impressionism, poets navi- In Short gated the indirect locutions of Symbolism, Born: August 22, 1862, in Saint-Germain- composers struggled with the pluses and mi- en-Laye, just outside Paris, France nuses of Wagner, and the City of Light blazed Died: March 25, 1918, in Paris even more brightly than usual, enflamed with the pleasures of the Belle Époque. Works composed and premiered: Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune begun in 1892 — Several early Debussy masterpieces of perhaps as early as 1891 — and completed the 1890s have lodged in the repertoire, by October 23, 1894; premiered December 22, including, most strikingly, the Prélude à 1894, at a concert of the Société Nationale de l’après-midi d’un faune. Debussy was hardly Musique in Paris, Gustave Doret, conductor. a youngster when he composed it. He had Nocturnes composed 1897–99, drawing on begun studying at the Paris Conservatoire material sketched as early as 1892; dedicated to in 1872, when he was only ten; had served the music publisher Georges Hartmann; Nuages as resident pianist and musical pet for Na- and Fêtes premiered on December 9, 1900, dezhda von Meck, Tchaikovsky’s myste- at the Concerts Lamoureux in Paris, Camille rious patron, in Russia and on her travels Chevillard, conductor; the complete three- during the summers of 1880–82; had finally movement Noctunes was premiered on October 27, 1901, by the same orchestra and conductor. -

<I>Rapsodie Pour Orchestre Et Saxophone</I>, by Claude Debussy

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Student Research Music 4-7-2008 Rapsodie pour Orchestre et Saxophone, by Claude Debussy Jonathon Blum Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/mus_stu_res Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Blum, Jonathon, "Rapsodie pour Orchestre et Saxophone, by Claude Debussy" (2008). Student Research. Paper 1. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/mus_stu_res/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Music Student Research Western Kentucky University Year Rapsodie pour Orchestre et Saxophone, by Claude Debussy Jonathon Blum Western Kentucky University, [email protected] This paper is posted at TopSCHOLAR. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/mus stu res/1 Rapsodie pour Orchestre et Saxophone, by Claude Debussy, Jonathon Blum The Rapsodie pour Orchestre et Saxophone composed by Claude Debussy is a very intriguing work that for all its musical merit remains pushed aside by many musicologists and ignored by the mainstream orchestral repertoire. Composed by Debussy in Paris in 1904 and published by Durand, this work lasts a duration of about ten minutes and features an orchestra with solo saxophone. 1 The piece was commissioned in 1903 by a wealthy Boston aristocrat/amateur saxophonist Mrs. Richard J. Hall, often referred to as Elise Hall. The Rapsodie was composed at the same time that Debussy was working on La Mer and when he was in a period of great distress in his own life. -

Embracing Nontraditional Scales and Tonal Structures, Claude Debussy Is

QUICK FACTS Claude Debussy, Composer BIRTH DATE August 22, 1862 DEATH DATE March 25, 1918 EDUCATION Paris Conservatory PLACE OF BIRTH Saint-Germaine Laye France, PLACE OF DEATH PARIS, FRANCE QUOTES “Music is the space between the notes.” Embracing nontraditional scales and tonal structures, Claude Debussy is one of the most highly regarded composers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and is seen as the founder of musical impressionism. Synopsis Claude Debussy was born into a poor family in France in 1862, but his obvious gift at the piano sent him to the Paris Conservatory at age 11. At age 22, he won the Prix de Rome, which financed two years of further musical study in the Italian capital. After the turn of the century, Debussy established himself as the leading figure of French music. During World War I, while Paris was being bombed by the German air force, he succumbed to colon cancer at the age of 55. Early Life Achille-Claude Debussy was born on August 22, 1862, in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France, the oldest of five children. While his family had little money, Debussy showed an early affinity for the piano, and he began taking lessons at the age of 7. By age 10 or 11, he had entered the Paris Conservatory, where his instructors and fellow students recognized his talent but often found his attempts at musical innovation strange. Clair de lune, meaning moonlight, was written by the Impressionist French composer Claude Debussy. Here’s everything you need to know about this piano masterpiece Claude Debussy started wrote the incredibly romantic piano piece Clair de Lune in 1890 when he was just 28, but it wasn’t published for another 15 years! The title means ‘Moonlight’ and the piece is actually part of the four-movement work Suite Bergamasque. -

Musical Elements in the Discrete-Time Representation of Sound

0 Musical elements in the discrete-time representation of sound RENATO FABBRI, University of Sao˜ Paulo VILSON VIEIRA DA SILVA JUNIOR, Cod.ai ANTONIOˆ CARLOS SILVANO PESSOTTI, Universidade Metodista de Piracicaba DEBORA´ CRISTINA CORREA,ˆ University of Western Australia OSVALDO N. OLIVEIRA JR., University of Sao˜ Paulo e representation of basic elements of music in terms of discrete audio signals is oen used in soware for musical creation and design. Nevertheless, there is no unied approach that relates these elements to the discrete samples of digitized sound. In this article, each musical element is related by equations and algorithms to the discrete-time samples of sounds, and each of these relations are implemented in scripts within a soware toolbox, referred to as MASS (Music and Audio in Sample Sequences). e fundamental element, the musical note with duration, volume, pitch and timbre, is related quantitatively to characteristics of the digital signal. Internal variations of a note, such as tremolos, vibratos and spectral uctuations, are also considered, which enables the synthesis of notes inspired by real instruments and new sonorities. With this representation of notes, resources are provided for the generation of higher scale musical structures, such as rhythmic meter, pitch intervals and cycles. is framework enables precise and trustful scientic experiments, data sonication and is useful for education and art. e ecacy of MASS is conrmed by the synthesis of small musical pieces using basic notes, elaborated notes and notes in music, which reects the organization of the toolbox and thus of this article. It is possible to synthesize whole albums through collage of the scripts and seings specied by the user.