Chestnut Commons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRA Evaluation Charter No. 16626

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE May 4, 2016 COMMUNITY REINVESTMENT ACT PERFORMANCE EVALUATION Central National Bank Charter Number 16626 8320 W. Highway 84, Waco, TX 76712 Office of the Comptroller of the Currency 225 E. John Carpenter Freeway, Suite 900, Irving, Texas 75062 NOTE: This document is an evaluation of this institution’s record of meeting the credit needs of its entire community, including low- and moderate-income neighborhoods consistent with safe and sound operation of the institution. This evaluation is not, nor should it be construed as, an assessment of the financial condition of this institution. The rating assigned to this institution does not represent an analysis, conclusion, or opinion of the federal financial supervisory agency concerning the safety and soundness of this financial institution. Charter Number 16626 INSTITUTION'S CRA RATING: This institution is rated Satisfactory. The Lending Test is rated: Satisfactory. The Community Development Test is rated: Outstanding. Major factors that support this Satisfactory rating include: • The bank’s loan-to-deposit (LTD) ratio is reasonable. • A majority of loan originations and purchases are within the bank’s assessment area (AA). • The distribution of residential and business loans to borrowers of different income levels exhibits reasonable penetration. • The bank’s geographic distribution of residential and business loans to low- and moderate-income (LMI) census tracts reflects reasonable dispersion. • The overall level of responsiveness of community development (CD) lending, investments, and services is excellent. 1 Charter Number 16626 Scope of Examination The Performance Evaluation (PE) assesses the bank’s record of meeting the credit needs of the communities in which it operates. -

City of Austin

OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED JULY 23, 2019 New Issues: Book-Entry-Only System Ratings: Moody’s: “A1” (stable outlook) S&P: “A” (positive outlook) Kroll: “AA-” (stable outlook) (See “OTHER RELEVANT INFORMATION – Ratings”) In the opinion of Bracewell LLP, Bond Counsel, under existing law, (i) interest on the 2019A Bonds is excludable from gross income for federal income tax purposes, and (ii) the 2019A Bonds are not “private activity bonds.” Further, in the opinion of Bond Counsel, under existing law, (i) interest on the 2019B Bonds is excludable from gross income for federal income tax purposes, except for any period during which a 2019B Bond is held by a person who is a “substantial user” of the facilities financed with the proceeds of the 2019B Bonds or a “related person” to such a “substantial user,” each within the meaning of section 147(a) of the Code and (ii) interest on the 2019B Bonds is an item of tax preference that is includable in alternative minimum taxable income for purposes of determining a taxpayer’s alternative minimum tax liability. See “TAX MATTERS” for a discussion of the opinions of Bond Counsel. CITY OF AUSTIN, TEXAS $16,975,000 $248,170,000 Airport System Revenue Bonds, Airport System Revenue Bonds, Series 2019A Series 2019B (AMT) Dated: August 1, 2019; Interest to accrue from Date of Initial Delivery Due: As shown on the inside cover page The $16,975,000 City of Austin, Texas Airport System Revenue Bonds, Series 2019A (the “2019A Bonds”) and the $248,170,000 City of Austin, Texas Airport System Revenue Bonds, Series 2019B (AMT) (the “2019B Bonds” and, collectively with the 2019A Bonds, the “Bonds”), are limited special obligations of the City of Austin, Texas (the “City”), issued pursuant to the ordinances adopted by the City on June 19, 2019 (the “Ordinances”). -

FY 2016 Operating & Capital Budget & 5 Year Capital Improvement Plan

PROPOSED FY 2016 Operating & Capital Budget & 5 Year Capital Improvement Plan Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority | Austin, Texas Capital Metropolitan Transportation Authority Proposed FY 2016 Operating and Capital Budget and Five Year Capital Improvement Plan Table of Contents Organization of the Budget Document ....................................................................................... 1 Transmittal Letter ....................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction History and Service Area ..................................................................................................... 4 Capital Metro Service Area Map .......................................................................................... 4 Community Information and Capital Metro Involvement ..................................................... 5 Benefits of Public Transportation......................................................................................... 6 Governance ......................................................................................................................... 7 Management ........................................................................................................................ 8 System Facility Characteristics ............................................................................................ 9 MetroRail Red Line Service Map ...................................................................................... -

Sounder Commuter Rail (Seattle)

Public Use of Rail Right-of-Way in Urban Areas Final Report PRC 14-12 F Public Use of Rail Right-of-Way in Urban Areas Texas A&M Transportation Institute PRC 14-12 F December 2014 Authors Jolanda Prozzi Rydell Walthall Megan Kenney Jeff Warner Curtis Morgan Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ 8 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. 9 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 10 Sharing Rail Infrastructure ........................................................................................................ 10 Three Scenarios for Sharing Rail Infrastructure ................................................................... 10 Shared-Use Agreement Components .................................................................................... 12 Freight Railroad Company Perspectives ............................................................................... 12 Keys to Negotiating Successful Shared-Use Agreements .................................................... 13 Rail Infrastructure Relocation ................................................................................................... 15 Benefits of Infrastructure Relocation ................................................................................... -

St. Mark's Medical Office Building Two St

ST. MARK'S MEDICAL OFFICE BUILDING TWO ST. MARK'S PLACE | LA GRANGE, TX 78945 OFFERING MEMORANDUM DISCLAIMER ST. MARK'S MEDICAL OFFICE BUILDING Colliers International Brokerage Company (“Broker“) has been retained as the exclusive advisor and broker for this offering. TWO ST. MARK'S PLACE This Offering Memorandum has been prepared by Broker for use by a limited number of parties and does not purport to provide a necessarily LA GRANGE, TX 78945 accurate summary of the Property or any of the documents related thereto, nor does it purport to be all-inclusive or to contain all of the information which prospective Buyers may need or desire. All projections have been developed by Broker and designated sources and are based upon assumptions relating to the general economy, competition, and other factors beyond the control of the Seller and therefore are subject to variation. No representation is made by Broker or the Seller as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein, and nothing contained herein shall be relied on as a promise or representation as to the future performance of the Property. Although the information contained EXCLUSIVE INVESTMENT ADVISORY TEAM herein is believed to be correct, the Seller and its employees disclaim any responsibility for inaccuracies and expect prospective purchasers to exercise independent due diligence in verifying all such information. Further, Broker, the Seller and its employees disclaim any and all liability for representations and warranties, expressed and implied, contained in or omitted from the Offering Memorandum or any other written or oral communication transmitted or made available to the Buyer. -

Transit Oriented Development: a Presentation for Partnerships In

Transit Oriented Development Austin, Texas A Presentation for Partnerships in Transit Workshop October 23, 2008 Doug Allen, Executive Vice President and Chief Development Officer Central Texas quality of life Quality public transportation can protect Austin’s way of life Austin residents say the number one challenge facing the Austin community is traffic congestion, according to a survey by Envision Central Texas. What are the most important issues to address to ensure a positive future for Central Texas? (choose three) Transportation/Congestion 66.6% Land Use 34.1% Cost of Living 30.9% Water Availability 28.2% Air Quality 27.8% –SOURCE: ECT online survey of Central Texas residents, 2008 Capital Metro Service Area: 500 square miles - Austin - Jonestown - Lago Vista - Leander - Manor - San Leanna - portion of Travis Co. - portion of Williamson Co. Capital Metro Today Fixed Route Bus System – 134 routes including local, express & “Dillo” trolley – 3,300 stops – 12 Park and Rides Texas Transit Association: “Best in Texas” – 2007 “Outstanding Metropolitan Transportation System” Highest per capita ridership in Texas – 140,000+ one-way trips every day – 36 million projected total annual boardings in 2009 All Systems Go! Long Range Transit Plan Layers of service –Local Bus Service –Express Bus –Capital MetroRail –Rapid Bus –Potential Future Service Capital MetroRail Overview Downtown Plaza Saltillo MLK, Jr. Highland Mall Crestview Kramer Howard Lakeline Leander MetroRail Stations Plaza Saltillo Leander Lakeline Transit Oriented Development: Capital Metro Goals Ridership—TOD housing provides riders. TOD commercial and retail provides destinations. Revenue—Sales tax. Property tax. For land we own, development revenue. Community—TOD adds another lifestyle choice to the regional portfolio. -

August 21, 2019

NEW ISSUE: BOOK-ENTRY-ONLY OFFERING MEMORANDUM Ratings: S&P: PSF Enhanced: “AAA”; Underlying: “AA+” August 21, 2019 Ratings: Fitch: PSF Enhanced: “AAA”; Underlying: “AA+” PSF Guarantee: “Conditionally Approved” (See “RATINGS” and “THE PERMANENT SCHOOL FUND GUARANTEE PROGRAM”.) In the opinion of Bond Counsel (identified below), assuming continuing compliance by the District (defined below) after the date of initial delivery of the Bonds (defined below) with certain covenants contained in the Order (defined below) and subject to the matters set forth under “TAX MATTERS” herein, interest on the Bonds for federal income tax purposes under existing statutes, regulations, published rulings, and court decisions (1) is not included in gross income of the owners thereof pursuant to section 103 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended to the date of initial delivery of the Bonds, and (2) is not an item of tax preference for purposes of the federal alternative minimum tax. See “TAX MATTERS” herein. Additionally, see “THE BONDS - Determination of Interest Rate; Rate Mode Changes” identifying circumstances when an opinion of nationally recognized bond counsel is required as a condition for an interest mode conversion. Bond Counsel expresses no opinion as to the effect on the excludability from gross income for federal income tax purposes of any action requiring such an opinion. $14,930,000 EANES INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT (A political subdivision of the State of Texas located in Travis County, Texas) VARIABLE RATE UNLIMITED TAX SCHOOL BUILDING BONDS, SERIES 2019B INITIAL TERM RATE PERIOD OF SIX YEARS AT A PER ANNUM INITIAL RATE OF 1.75% (PRICED TO YIELD 1.35% TO FIRST OPTIONAL REDEMPTION DATE OF AUGUST 1, 2024) Dated Date: September 1, 2019 (interest will accrue from the Delivery Date) Mandatory Tender Date: August 1, 2025 CUSIP No. -

Plum Creek Kyle Texas

Plum Creek Kyle, Texas Project Type: Residential Case No: C036013 Year: 2006 SUMMARY Plum Creek is a master-planned community located in Kyle, Texas, approximately 20 miles (32 kilometers) south of Austin. Developed by Benchmark Land Development, it is the first large-scale community in the Austin metropolitan area built according to the principles of new urbanism. At buildout, the 2,200-acre (890-hectare) development will contain up to 8,700 homes, a mixed-use town center, employment districts, and a commuter rail station. FEATURES Master-Planned Community—Large Scale Transit-Oriented Development Pedestrian-Friendly Design Traditional Neighborhood Development Plum Creek Kyle, Texas Project Type: Residential Subcategory: Planned Communities Volume 36 Number 13 July–September 2006 Case Number: C036013 PROJECT TYPE Plum Creek is a master-planned community located in Kyle, Texas, approximately 20 miles (32 kilometers) south of Austin. Developed by Benchmark Land Development, it is the first large-scale community in the Austin metropolitan area built according to the principles of new urbanism. At buildout, the 2,200-acre (890-hectare) development will contain up to 8,700 homes, a mixed-use town center, employment districts, and a commuter rail station. LOCATION Outer Suburban SITE SIZE 2,200 acres/890 hectares LAND USES Single-Family Detached Residential, Townhouses, Condominiums, Apartments, Neighborhood Retail Center, Schools, Golf Course, Open Space KEYWORDS/SPECIAL FEATURES Master-Planned Community—Large Scale Transit-Oriented Development Pedestrian-Friendly Design Traditional Neighborhood Development PROJECT WEB SITE www.plumcreektx.com DEVELOPER Benchmark Land Development, Inc. Austin, Texas 512-472-7455 www.benchmarktx.net LAND PLANNER TBG Partners, Inc. -

CITY of ROUND ROCK TRANSIT PLAN Existing Conditions Report

[NAME OF DOCUMENT] | VOLUME [Client Name] CITY OF ROUND ROCK TRANSIT PLAN Existing Conditions Report June 2015 Nelson\Nygaard Consulting Associates Inc. | i Round Rock Transit Plan - Existing Conditions Report City of Round Rock Table of Contents Page 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................1-1 2 Document Review ............................................................................................................2-2 Round Rock General Plan 2020 ......................................................................................................... 2-2 Round Rock Transportation Master Plan ........................................................................................... 2-3 Round Rock Downtown Master Plan ................................................................................................... 2-3 Project Connect ....................................................................................................................................... 2-4 Commuter Express Bus Plan ................................................................................................................. 2-7 3 Review of Existing Services .............................................................................................3-1 Demand Response ................................................................................................................................. 3-1 Reverse Commute ................................................................................................................................. -

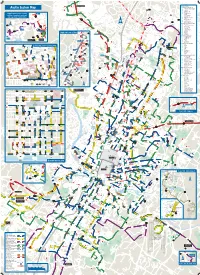

Austin System Map G 1L N

Leander Leander Park & Ride 983 986 987 183 S o u t h B e l l Bl vd 983 986 987 214 214 ne Blvd testo 1431 Whi r D n e re 214 rg e v E Main 214 St 1431 La ke li ne 214 B lv 983 Jonestown d Park & Ride 985 214 d el R ur a L 214 Bro nc o d R Bar-K anch L R n LeanderLeander Lago Vista HS Park & Ride 183 214 183 Rd ch Lakeline an Post Office 383 214 R K Co r- yo 983 987 Northwest a te B Tr 214 383 Park & Ride P a 214 383 s P 983 985 e e o d 985 983 985 987 c R 987 a d n e P d a r r k d V o lv a B F 214 B c l Lakeline v p a to n d es k a 383 a Mall L R d m Pace Bend h North Fork o Recreation Area L Plaza (LCRA-County) 1431 383 Forest North ES WalMart 983 1431 Lakeline Plaza 985 1 Jonestown 987 TOLL Park & Ride Target Lago Vista 214 Park & Ride D 183 aw Lakeline 214 n Rd Northwest Park & Ride ek ke Cre Routes 383, 983, 985 and 987 La Pkwy continue, see inset at left. Route Finder Grisham MS M i l Westwood HS l Local Service Routes (01-99) w 1 r i TOLL Austin System Map g 1L N. Lamar/S. Congress, via Lamar S Lago Vista h ho Anderson t r 1M N. -

Getting Around in Austin

GETTING AROUND IN AUSTIN Austin-Bergstrom International Airport (AUS) Austin-Bergstrom International Airport (ABIA) is a state-of-the-art airport with 25 gates, full customs facilities ready for the international traveler, and two parallel runways including a 12,250 foot runway. Easy to get to (only seven and a half miles from the Austin Convention Center), the airport saw an all-time passenger record of nearly 11.9 million passengers in 2015, up 11% from 2014. In operation since 1999, the airport has roughly 300 daily flights with nonstop service to 45+ destinations including international flights to London, Cancun, Guadalajara, San Jose Del Cabo and Toronto, and seasonal summer flights to Frankfurt, Germany. Austin is one of only seven airports with year-round service to all United Airlines hubs. Live music has been a distinguishing feature of the airport since its Music in the Air program launched in June 1999, just one month after the airport opened. What started as two performances per week has grown to 23 shows per week in six different venues throughout the airport: Ray Benson’s Roadhouse, the Saxon Pub, Annie’s Café & Bar, Earl Campbell’s Sports Bar, Austin City Limits/Waterloo Records & Video, and Ruta Maya. ABIA participates in the Transportation Security Administration’s (TSA) Pre-Check and Customs and Border Protection’s Global Entry program. Construction begins in 2016 on a nine-gate terminal expansion. ABIA reported 1,190 live music performances, 65.5 tons of brisket and 693,375 breakfast tacos were enjoyed by its passengers in 2015. ABIA ranked third among airports in North America for Airport Service Quality (ASQ) in 2015. -

Evaluation of Two Monitoring Systems for Significant Bridges in Texas

Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA/TX-04/0-4096-1 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date Evaluation of Two Monitoring Systems for Significant January 2004 Bridges in Texas 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. C. T. Bilich and S. L. Wood Research Report 0-4096-1 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Center for Transportation Research 11. Contract or Grant No. The University of Texas at Austin Research Project 0-4096 3208 Red River, Suite 200 Austin, TX 78705-2650 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Texas Department of Transportation Research Report (9/01- 8/03) Research and Technology Implementation Office P.O. Box 5080 Austin, TX 78763-5080 14. Sponsoring Agency Code 15. Supplementary Notes Project conducted in cooperation with the U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, and the Texas Department of Transportation 16. Abstract Two monitoring systems for bridges were evaluated for use by the Texas Department of Transportation. The first system was designed to increase the quantitative information obtained during a routine inspection of a steel bridge. The miniature, battery-powered data acquisition system selected for study has the ability to record a single channel of strain data and use a rainflow counting algorithm to evaluate the raw data. This system was considered to be particularly useful for evaluating fracture critical bridges. The second system provided long-term monitoring of bridge displacements using global positioning systems (GPS).