When (Im)Perfective Is Perfect (And When It Is Not)*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perfect Tenses 8.Pdf

Name Date Lesson 7 Perfect Tenses Teaching The present perfect tense shows an action or condition that began in the past and continues into the present. Present Perfect Dan has called every day this week. The past perfect tense shows an action or condition in the past that came before another action or condition in the past. Past Perfect Dan had called before Ellen arrived. The future perfect tense shows an action or condition in the future that will occur before another action or condition in the future. Future Perfect Dan will have called before Ellen arrives. To form the present perfect, past perfect, and future perfect tenses, add has, have, had, or will have to the past participle. Tense Singular Plural Present Perfect I have called we have called has or have + past participle you have called you have called he, she, it has called they have called Past Perfect I had called we had called had + past participle you had called you had called he, she, it had called they had called CHAPTER 4 Future Perfect I will have called we will have called will + have + past participle you will have called you will have called he, she, it will have called they will have called Recognizing the Perfect Tenses Underline the verb in each sentence. On the blank, write the tense of the verb. 1. The film house has not developed the pictures yet. _______________________ 2. Fred will have left before Erin’s arrival. _______________________ 3. Florence has been a vary gracious hostess. _______________________ 4. Andi had lost her transfer by the end of the bus ride. -

Greek Verb Aspect

Greek Verb Aspect Paul Bell & William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 21, 2012 The technical literature concerning aspect is vast and difficult. The goal of this tutorial is to present, as gently as possible, a few more or less commonly held opinions about aspect. Although these opinions may be championed by one academic quarter and denied by another, at the very least they should shed some light on an abstruse matter. Introduction The word “aspect” has its roots in the Latin verb specere meaning “to look at.” Aspect is concerned with how we view a particular situation. Hence aspect is subjective – different people will view the same situation differently; the same person can view a situation differently at different times. There is little doubt that how we see things depends on our psychological state at the mo- ment of seeing. The ‘choice’ to bring some parts of a situation into close, foreground relief while relegating others to an almost non-descript background happens unconsciously. But for one who must describe a situation to others, this choice may indeed operate consciously and deliberately. Hence aspect concerns not only how one views a situation, but how he chooses to relate, to re-present, a situation. A Definition of Aspect But we still haven’t really said what aspect is. So here’s a working definition – aspect is the dis- closure of a situation from the perspective of internal temporal structure. To put it another way, when an author makes an aspectual choice in relating a situation, he is choosing to reveal or conceal the situation’s internal temporal structure. -

The Formation, Translation and Use of Participles in Latin, and the Nature of Relative Time

Chapter 23: Participles Chapter 23 covers the following: the formation, translation and use of participles in Latin, and the nature of relative time. At the end of the lesson we’ll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There are four important rules to remember in Chapter 23: (1) Latin has four participles: the present active, the future active; the perfect passive and the future passive. It lacks, however, a present passive participle (“being [verb]-ed”) and a perfect active participle (“having [verb]-ed”). (2) The perfect passive, future active and future passive participles belong to first/second declension. The present active participle belongs to third declension. (3) The verb esse has only a future active participle (futurus). It lacks both the present active and all passive participles. (4) Participles show relative time. What are participles? At heart, participles are verbs which have been turned into adjectives. Thus, technically participles are “verbal adjectives.” The first part of the word (parti-) means “part;” the second part (-cip-) means “take,” indicating that participles “partake, share” in the characteristics of both verbs and adjectives. In other words, the base of a participle is verbal, giving it some of the qualities of a verb, for instance, tense: it can indicate when the action is happening (now or then or later; i.e. present, past or future); conjugation: what thematic vowel will be used (e.g. -a- in first conjugation, -e- in second, and so on); voice: whether the word it’s attached to is acting or being acted upon (i.e. -

Perfect-Traj.Pdf

Aspect shifts in Indo-Aryan and trajectories of semantic change1 Cleo Condoravdi and Ashwini Deo Abstract: The grammaticalization literature notes the cross-linguistic robustness of a diachronic pat- tern involving the aspectual categories resultative, perfect, and perfective. Resultative aspect markers often develop into perfect markers, which then end up as perfect plus perfective markers. We intro- duce supporting data from the history of Old and Middle Indo-Aryan languages, whose instantiation of this pattern has not been previously noted. We provide a semantic analysis of the resultative, the perfect, and the aspectual category that combines perfect and perfective. Our analysis reveals the change to be a two-step generalization (semantic weakening) from the original resultative meaning. 1 Introduction The emergence of new functional expressions and the changes in their distribution and interpretation over time have been shown to be systematic across languages, as well as across a variety of semantic domains. These observations have led scholars to construe such changes in terms of “clines”, or predetermined trajectories, along which expressions move in time. Specifically, the typological literature, based on large-scale grammaticaliza- tion studies, has discovered several such trajectorial shifts in the domain of tense, aspect, and modality. Three properties characterize such shifts: (a) the categories involved are sta- ble across cross-linguistic instantiations; (b) the paths of change are unidirectional; (c) the shifts are uniformly generalizing (Heine, Claudi, and H¨unnemeyer 1991; Bybee, Perkins, and Pagliuca 1994; Haspelmath 1999; Dahl 2000; Traugott and Dasher 2002; Hopper and Traugott 2003; Kiparsky 2012). A well-known trajectory is the one in (1). -

<HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> in ROMANCE and ENGLISH

<HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> IN ROMANCE AND ENGLISH: SYNCHRONY AND DIACHRONY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Diego A. de Acosta May 2006 © 2006 Diego A. de Acosta <HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> IN ROMANCE AND ENGLISH: SYNCHRONY AND DIACHRONY Diego A. de Acosta, Ph.D. Cornell University 2006 Synopsis: At first glance, the development of the Romance and Germanic have- perfects would seem to be well understood. The surface form of the source syntagma is uncontroversial and there is an abundant, inveterate literature that analyzes the emergence of have as an auxiliary. The “endpoints” of the development may be superficially described as follows (for English): (1) OE Ic hine ofslægenne hæbbe > Eng I have slain him The traditional view is that the source syntagma, <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle>, is structured [have [noun participle]], and that this syntagma undergoes change as have loses its possessive meaning. In this dissertation, I demonstrate that the traditional view is untenable and readdress two fundamental questions about the development of have-perfects: (i) how is the early ability of have to predicate possession connected with its later role in the perfect?; (ii) what are the syntactic structures and meanings of <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle> before the emergence of the have-perfect? With corpus evidence, I show that that the surface string <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle> corresponds to three different structures in Old English and Latin; all of these survive into modern English and the Romance languages. -

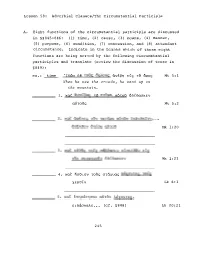

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight functions of the circumstantial participle are discussed in §§845-846: (1) time, (2) cause, (3) means, (4) manner, (5) purpose, (6) condition, (7) concession, and (8) attendant circumstance. Indicate in the blanks which of these eight functions are being served by the following circumstantial participles and translate (review the discussion of tense in §849) : ex.: time -Iowv o� �o�� 5XAOU� aVE�n EL� �b 5po� Mt 5:1 When he saw the orowds, he went up on the mountain. 1. Kat avoLEa� �b o�oHa au�ou EOLoaoKEv au�o�� Mt 5:2 Mk 1:20 Mk 1:21 4. Kat no8Lov �o�� o�axua� WWXOV�E� �aC� XEPOLV Lk 6:1 ALoaaKaAE • • • (cf. §848) Lk 20:21 245 246 6. xat &auuaoav�E� En� �fj anoxpCoE� au�oG EOCYnOav Lk 20:26 7. TaG�a �a pnua�a EAaAnOEv EV �� yako �uAaxl� o�oaoxwv EV �Q tEPQ In 8:20 Acts 10:27 B. As a modifier, a circumstantial participle agrees in gender, number and case with its antecedent (§8460) in the sentence unless it has its own subject in a genitive absolute con struction (§847). Underline the antecedents or subjects of the participles in the following sentences and translate (note §8470): 1. Ka�aBav�o� 08 au�ou an� �oG opou� nXOAou&noav au�� OXAO� nOAAol Mt 8:1 Mt 22:18 Mk 1:40 Mk 2:23 247 5. Kat AEYEL aULoL� tv tXElv� Lij nUEP� 6�Ca� YEVOUEVT)� Mk 4:3 5 c. Prepare Gal 1:11-24 (from selection #26) for class trans lation. -

The Aorist in Modern Armenian: Core Value and Contextual Meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos

The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos To cite this version: Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos. The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual mean- ings. Zlatka Guentcheva. Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, pp.375 - 412, 2016, 9789027267610. 10.1075/slcs.172.12don. halshs-01424956 HAL Id: halshs-01424956 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01424956 Submitted on 6 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings, in Guentchéva, Zlatka (ed.), Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, 2016, p. 375-411 (the published paper miss examples written in Armenian) The aorist in Modern Armenian: core values and contextual meanings Anaïd Donabédian (SeDyL, INALCO/USPC, CNRS UMR8202, IRD UMR135) Introduction Comparison between particular markers in different languages is always controversial, nevertheless linguists can identify in numerous languages a verb tense that can be described as aorist. Cross-linguistic differences exist, due to the diachrony of the markers in question and their position within the verbal system of a given language, but there are clearly a certain number of shared morphological, syntactic, semantic and/or pragmatic features. -

The Perfect Dilemma: Aspect in the Koine Greek Verbal System, Accepted and Debated Areas of Research

Perfect Dilemma 1 Running head: PERFECT DILEMMA The Perfect Dilemma: Aspect in the Koine Greek Verbal System, Accepted and Debated Areas of Research Christopher H. Johnson A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2009 Perfect Dilemma 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Wayne Brindle, Th.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ David Croteau, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Paul Muller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date Perfect Dilemma 3 Abstract Verbal aspect is a recent but very promising field of study in Koine Greek, which seeks to describe the semantic meaning of the verbal forms. This study surveys the works of the leading contributors in this field and offers critiques of their major points. The subject matter is divided into three sections: methods, areas of agreement, and areas of dispute, with a focus on the latter. Overall, scholarship has provided a more accurate description of the Greek verbal system through the theory of verbal aspect, though there are topics that need further research. This study’s suggestions may aid in developing verbal aspect and substantiating certain features of its theory. Perfect Dilemma 4 Introduction “There is a prevalent but false assumption that everything in NT Greek scholarship has been done already,”1 so argues Lars Rydbeck as he urges scholars to continue to work in studying the Koine language. His appeal has been answered by numerous studies in Koine Greek and in the developments in its grammar. -

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615 Richards, Ivor Armstrong 1936 The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rockwell, Patricia 2007 Vocal features of conversational sarcasm: A comparison of methods. Journal of Psycho- linguistic Research 36: 361−369. Rosenblum, Doron 5. March 2004 Smart he is not. http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/opinion/smart-he-is-not- 1.115908. Searle, John 1979 Expression and Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Seddiq, Mirriam N. A. Why I don’t want to talk to you. http://notguiltynoway.com/2004/09/why-i-dont-want- to-talk-to-you.html. Singh, Onkar 17. December 2002 Parliament attack convicts fight in court. http://www.rediff.com/news/ 2002/dec/17parl2.htm [Accessed 24 July 2013]. Sperber, Dan and Deirdre Wilson 1986/1995 Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell. Voegele, Jason N. A. http://www.jvoegele.com/literarysf/cyberpunk.html Voyer, Daniel and Cheryl Techentin 2010 Subjective acoustic features of sarcasm: Lower, slower, and more. Metaphor and Symbol 25: 1−16. Ward, Gregory 1983 A pragmatic analysis of epitomization. Papers in Linguistics 17: 145−161. Ward, Gregory and Betty J. Birner 2006 Information structure. In: B. Aarts and A. McMahon (eds.), Handbook of English Lin- guistics, 291−317. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Rachel Giora, Tel Aviv, (Israel) 30. Tense Aspect Mood 1. Introduction 2. Metaphor: EVENTS ARE (PHYSICAL) OBJECTS 3. Polysemy, construal, profiling, and coercion 4. Interactions of tense, aspect, and mood 5. Conclusion 6. References 1. Introduction In the framework of cognitive linguistics we approach the grammatical categories of tense, aspect, and mood from the perspective of general cognitive strategies. -

Language Reference

Language reference Unit 1 | Tenses Past perfect Present simple Use the past perfect to put events in the past in sequence. The past perfect indicates that the action it refers to happened before a Use the present simple reference to the past simple. 1 to talk about general facts, states, and situations I had heard from the locals that there were several interesting sites. The purpose of business is to make a profit. 2 to talk about regular or repeated actions, or permanent situations Past perfect continuous Jack works for Nissan. Use the past perfect continuous to refer to an action in progress before something else happened. 3 to talk about timetabled future events He was the one who had been working on the project, but his boss The meeting starts at 10.00. was the one who got all the credit. Present continuous Should Use the present continuous 1 Use should + infinitive to recommend something strongly. 1 to talk about an action in progress at the time of speaking / You should try that vegetarian restaurant on the river. writing 2 Use should + perfect infinitive to talk about a lost opportunity. I’m trying to get through to Jon Berks. You should have gone this morning – it was quite an interesting 2 to talk about a very current activity, taking place around the time meeting. of speaking 3 Use could / should + infinitive to predict. They are pushing the area for development. It could / should turn out to be quite an interesting conference. 3 to talk about fixed plans or arrangements in the future I am meeting the management committee on Friday. -

Grammar 4 – the Perfect Tenses the Present Perfect – an Introduction

Grammar 4 – The Perfect Tenses Welcome to a minefield! No, it’s not all that bad really, although gaining mastery of the Perfect Tense system is something which many students find difficult. Some students master the present and past, and appear to embrace the future forms with relative ease, yet fail to comprehend how and when to use the Perfect Tenses. We have seen many a good intermediate student fail to make additional progress because they have been unable to get to grips with this tense. So what is it all about? In this section we will look at 3 perfect forms; Past, Present and Future. The Present Perfect – an introduction The Present Perfect is a way of linking the past to the present. Whether it exists in other languages or not, it is a traditionally difficult concept for students to grasp and a notorious bugbear for teachers. A good sign of fluency in the English language is the ability to use it correctly. Do not attempt to teach the Present Perfect without the aid of a good grammar book (at least until you are familiar with it - we recommend ‘The Good Grammar Book’ by Swan). It is worth ensuring you become familiar with this tense as common interview questions for jobs include the following: ‘Describe the 3 uses of the Present Perfect’ ‘How would you approach a lesson on the Present Perfect?’ ‘How would you explain the difference between the Past Simple and the Present Perfect Tenses to a class?’ By the end of this module you should be able to answer these questions. -

Notes on Aorist Morphology

Notes on Aorist Morphology William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 5, 2012 Traditional grammars of classical Greek enumerate two forms of the aorist. For beginners this terminology is extremely misleading: the second aorist contains two distinct conjugations. This article covers the formation of all types of aorist, with special attention on the athematic second aorist conjugation which few verbs take, but several of them happen to be common. Not Two, but Three Aorists The forms of Greek aorist are usually divided into two classes, the first and the second. The first aorist is pretty simple, but the second aorist actually holds two distinct systems of morphology. I want to point out that the difference between first and second aorists is only a difference in conjugation. The meanings and uses of all these aorists are the same, but I’m not going to cover that here. See Goodwin’s Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb, or your favorite Greek grammar, for more about aorist syntax. In my verb charts I give the indicative active forms, indicate nu-movable with ”(ν)”, and al- ways include the dual forms. Beginners can probably skip the duals unless they are starting with Homer. The First Aorist This is taught as the regular form of the aorist. Like the future, a sigma is tacked onto the stem, so it sometimes called the sigmatic aorist. It is sometimes also called the weak aorist. Since it acts as a secondary (past) tense in the indicative, it has an augment: ἐ + λυ + σ- Onto this we tack on the endings.