India: Energy Issues

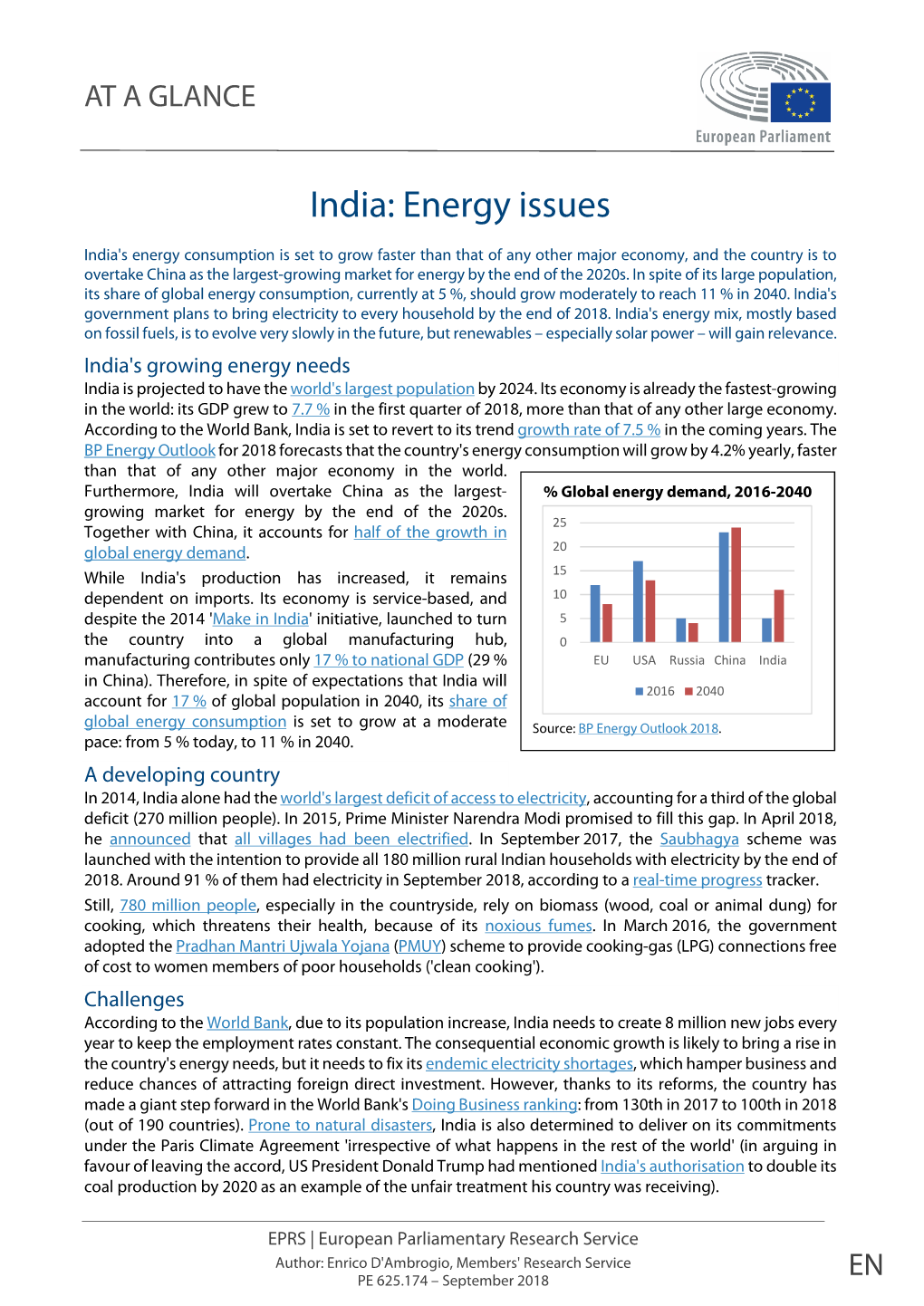

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joint Statement on the Occasion of the 7Th India-Japan Energy Dialogue

Joint Statement on the occasion of the 7th India-Japan Energy Dialogue between the Planning Commission of India and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan 1. H.E. Mr. Montek Singh Ahluwalia, Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission of India and H.E. Mr. Toshimitsu Motegi, Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan held the 7th meeting of the India-Japan Energy Dialogue on September 12, 2013 in New Delhi. 2. Senior officials of the relevant ministries and departments of both sides participated in the discussions. Both sides welcomed the progress achieved so far in the previous six rounds of the Energy Dialogue and in the deliberations of the various Working Groups. They appreciated the sector-specific discussions by experts of both sides and the progress made in various areas of cooperation. 3. During the dialogue, both sides recognized that it is important to hold the India-Japan Energy Dialogues annually, and that the issues of energy security and global environment are high priority challenges requiring continuous and effective action. In particular, to overcome challenges such as the global-scale changes in the energy demand structure seen in recent years and soaring energy prices, both sides confirmed to strengthen consumer-producer dialogue on LNG and deepen cooperation in energy conservation and renewable energy sectors. In addition, both sides decided to strengthen programs to further disseminate and expand model business projects that have thus far been implemented by both sides, and to enhance cooperation in upstream development of petroleum and natural gas. 4. Both sides recognized the need to promote industrial cooperation to expand bilateral energy cooperation on a commercial basis, based on the Joint Statement issued at the 6th India-Japan Energy Dialogue. -

US Energy Exports to India

Vol. 3, Issue 5 May 2013 U.S. Energy Exports to India: A Game India’s Energy by the Numbers Changer 75% Amb. Karl F. Inderfurth and Persis Khambatta Of India’s energy is imported; by 2023 the number is expected to rise to 90 percent. When Indian foreign secretary Ranjan Mathai came to Washington in February, energy was high on his agenda. Energy cooperation, he said, 4th “could be a real big game changer…You will start a chain of investments Largest energy consumer in the world. As India’s far bigger than anything we’ve had before.” He found a highly receptive energy needs have vastly increased, it has been audience with high-ranking officials at the State and Energy Departments. unable to develop sufficient domestic energy With the policy communities in both capitals consistently looking for “the production capabilities and therefore relies heavily next big thing” on the horizon for the U.S.-India strategic partnership, the on imports to meet its energy demands. past few months have seen a potential breakthrough to expand U.S. 6th exports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to India, which may lead to a big opportunity benefitting both countries. Largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) importer in the world. Until 2004, India produced all of its Changing Global Energy Landscape own LNG; in 2009, 21 percent of India’s total The United States and India are two of the world’s top five energy natural gas was imported. Importing is a financial consumers. To date, policy debates have focused on finding sustainable burden on federal funds, as imported LNG costs ways to satisfy the ever-expanding demand for energy by advanced twice as much as that produced domestically. -

IBEF Presentataion

OIL and GAS For updated information, please visit www.ibef.org November 2017 Table of Content Executive Summary……………….….…….3 Advantage India…………………..….……...4 Market Overview and Trends………..……..6 Porters Five Forces Analysis.….…..……...28 Strategies Adopted……………...……….…30 Growth Drivers……………………..............33 Opportunities…….……….......…………..…40 Success Stories………….......…..…...…....43 Useful Information……….......………….….46 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY . In FY17, India had 234.5 MMTPA of refining capacity, making it the 2nd largest refiner in Asia. By the end of Second largest refiner in 2017, the oil refining capacity of India is expected to rise and reach more than 310 million tonnes. Private Asia companies own about 38.21 per cent of total refining capacity World’s fourth-largest . India’s energy demand is expected to double to 1,516 Mtoe by 2035 from 723.9 Mtoe in 2016. Moreover, the energy consumer country’s share in global primary energy consumption is projected to increase by 2-folds by 2035 Fourth-largest consumer . In 2016-17, India consumed 193.745 MMT of petroleum products. In 2017-18, up to October, the figure stood of oil and petroleum at 115.579 MMT. products . India was 3rd largest consumer of crude oil and petroleum products in the world in 2016. LNG imports into the country accounted for about one-fourth of total gas demand, which is estimated to further increase by two times, over next five years. To meet this rising demand the country plans to increase its LNG import capacity to 50 million tonnes in the coming years. Fourth-largest LNG . India increasingly relies on imported LNG; the country is the fourth largest LNG importer and accounted for importer in 2016 5.68 per cent of global imports. -

Nuclear Energy in India's Energy Security Matrix

Nuclear Energy in India’s Energy Security Matrix: An Appraisal 2 of 55 About the Author Maj Gen AK Chaturvedi, AVSM, VSM was commissioned in Corps of Engineers (Bengal Sappers) during December 1974 and after a distinguished career of 38 years, both within Engineers and the staff, retired in July 2012. He is an alumnus of the College of Military Engineers, Pune; Indian Institute of Technology, Madras; College of Defence Management, Secunderabad; and National Defence College, New Delhi. Post retirement, he is pursuing PhD on ‘India’s Energy Security: 2030’. He is a prolific writer, who has also been quite active in lecture circuit on national security issues. His areas of interests are energy, water and other elements of ‘National Security’. He is based at Lucknow. http://www.vifindia.org © Vivekananda International Foundation Nuclear Energy in India’s Energy Security Matrix: An Appraisal 3 of 55 Abstract Energy is essential for the economic growth of a nation. India, which is in the lower half of the countries as far as the energy consumption per capita is concerned, needs to leap frog from its present position to upper half, commensurate with its growing economic stature, by adopting an approach, where all available sources need to be optimally used in a coordinated manner, to bridge the demand supply gap. A new road map is needed to address the energy security issue in short, medium and long term. Solution should be sustainable, environment friendly and affordable. Nuclear energy, a relatively clean energy, has an advantage that the blueprint for its growth, which was made over half a century earlier, is still valid and though sputtering at times, but is moving steadily as envisaged. -

Human Reliability Program in Industries of National Importance Jointly Organised by Nias, India and Texas A&M University, Usa

M. Sai Baba Sunil S. Chirayath SUMMARY OF THE MEETINGS ON HUMAN RELIABILITY PROGRAM IN INDUSTRIES OF NATIONAL IMPORTANCE JOINTLY ORGANISED BY NIAS, INDIA AND TEXAS A&M UNIVERSITY, USA NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED STUDIES Bengaluru, India January 2021 Report NIAS/NSE/U/MR/02/2021 Summary of the Meetings on Human Reliability Program in Industries of National Importance Jointly organised by NIAS, India and Texas A&M University, USA M. Sai Baba Sunil S. Chirayath NATIONAL INS TITUTE OF TEXAS A&M UNIVERS ITY USA ADVANCED STUDIES Bengaluru, India © National Institute of Advanced Studies, January 2021 Published by National Institute of Advanced Studies Indian Institute of Science Campus Bengaluru - 560 012 Tel: 2218 5000, Fax: 2218 5028 E-mail: [email protected] NIAS Report: NIAS/NSE/U/MR/02/2021 Typeset & Printed by Aditi Enterprises [email protected] Preface Human Reliability (to describe human performance) is widely used in fields requiring high standards of safety, such as aviation, petroleum and chemical processes, and nuclear industries. Human behavior always poses an inherent risk through our actions or inactions. Introducing errors into the operation of a system or process. Human factors can either positively or negatively affect the performance in workplace. Although human errors can be minimized through education and training/retraining programs, there are some human actions (insider actions) that could be intentional, which compromise the safety and security at the workplace due to ideological, economic, political, or personal motivations. A Human Reliability Program (HRP) could ensure that individuals who occupy positions with access to critical assets/operations/sites meet the highest standards so that they adhere to safety and security rules and regulations (reliability), ensure confidence in individuals based on their character (trustworthiness) and their physical and mental stability. -

Harnessing India's Productive Potential Through Renewables And

Harnessing India’s Productive Potential through Renewables and Jobs SABINA DEWAN INTRODUCTION *CAGR: Compound Annual Growth Rate of CO2 emissions The blackout in July 2012 that left over 600 million hoods, especially when compared to non-renewable people without electricity highlighted India’s inability energy sectors such as the coal industry. to meet its economy’s voracious appetite for energy. Yet with the enormous challenge of meeting India’s grow- Renewables are not a panacea. Scaling up production of ing energy demand comes an opportunity to leverage renewable energy in India is constrained by factors such the production of renewables - biomass, mini-hydro, as cost, pricing, and diffuse geography.1 Yet renewables solar, and wind - to expand the country’s energy sup- can be part of the solution in generating more and bet- ply while helping to address the employment challenges ter employment, raising productivity and shifting the also plaguing the nation. nation onto a cleaner, more sustainable growth trajec- tory. Flagging economic growth in recent years, coupled with joblessness and underemployment, has created the dual These potential dividends should further strengthen the imperative of generating more employment and en- new government’s resolve to scale up the production of hancing productivity. Renewables hold the potential to renewables and maximize their potential to generate help address both these aims. good employment in the process. • First, investment in renewables spurs new jobs in grid THE JOBS, POWER, AND construction and upgrading to smart grids, production PRODUCTIVITY DEFICIT of small-scale renewables, distribution, installation, and maintenance. Despite India’s average annual growth rate of 8.5% • Second, by improving energy supply, renewables can between 2005 and 2010,2 employment only grew at stimulate greater productivity across sectors. -

ENERGY STATISTICS 2019 (Twenty Sixth Issue)

ENERGY STATISTICS 2019 (Twenty Sixth Issue) CENTRAL STATISTICS OFFICE MINISTRY OF STATISTICS AND PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI ENERGY STATISTICS 2019 2 Officers associated with the publication: Officers associated with the publication: Smt. G.S. Lakshmi Additional Director General Smt. Bhawna Singh Director Shri Amit Kamal Deputy Director Ms. Shobha Sharma Assistant Director Shri Vijay Kumar Junior Statistical Officer ENERGY STATISTICS 2019 3 CONTENTS CONTENTS PAGE Energy Maps of India 6-8 Map 1: Installed Generation Capacity in India 6 Map 2: Wind Power Potential at 100m agl 7 Map 3: Refineries and Petroleum product Pipelines 8 Metadata-Energy Statistics 9-12 Highlights of Energy Statistics 2019 13 Chapter 1 : Reserves and Potential for Generation 14-20 Highlights and Graphs 14-17 Table 1.1: State-wise Estimated Reserves of Coal 18 Table 1.1(A): State-wise Estimated Reserves of Lignite 18 Table 1.2:State-wise Estimated Reserves of Crude Oil and Natural Gas 19 Table 1.3: Source wise and State wise Estimated Potential of Renewable Power 20 Chapter 2 : Installed Capacity and Capacity Utilization 21-33 Highlights and Graphs 21-24 Table 2.1 : Installed Capacity of Coal Washeries in India 25-26 Table 2.2 : Installed Capacity and Capacity Utilization of Refineries of Crude Oil 27 Table 2.3 : Installed Generating Capacity of Electricity in Utilities and Non Utilities 28 Table2.4 : Region-wise and State-wise Installed Generation Capacity of 29 Electricity(Utilities) Table 2.5 : State wise and Source wise Total Installed -

Energy Statistics 2018

Energy Statistics 2018 ENERGY STATISTICS 2018 (Twenty Fifth Issue) CENTRAL STATISTICS OFFICE MINISTRY OF STATISTICS AND PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI CENTRAL STATISTICS OFFICE Energy Statistics 2018 FOREWORD Energy is one of the most important building blocks in human development, and as such, acts as a key factor in determining the economic development of all the countries. In an effort to meet the demands of a developing nation, the energy sector has witnessed a rapid growth. It is important to note that non-renewable resources are significantly depleted by human use, whereas renewable resources are produced by ongoing processes that can sustain indefinite human exploitation. The use of renewable resources of energy is rapidly increasing worldwide. Solar power, one of the potential energy sources, is a fast developing industry in India. The country's solar installed capacity has reached 12.28 GW in year 2016-17 as compared to 6.76 GW during the year 2015-16. India has expanded its solar generation capacity by 5.52 GW during last one year which has led to downward trend in the cost and has increased usage. It clearly signifies that proper integration of policy interventions holds the key to achieve the sustainable development goals. This publication, 25th in the series is an annual publication of CSO and is a continued effort to provide a comprehensive picture of Energy Sector in India. Energy Statistics is an integrated and updated database of reserves, installed capacity, production, consumption, import, export and whole sale prices of different sources viz. coal, crude petroleum, natural gas and electricity. -

India's Primary Energy Evolution: Past Trends and Future Prospects

KAUSHIK DEB* Group Economics, BP plc PAUL APPLEBY† Group Economics, BP plc India’s Primary Energy Evolution: Past Trends and Future Prospects ABSTRACT This paper assesses India’s primary energy mix and changes in con- sumption and production to identify factors causing these changes and their likely economic and emission impacts. A rising GDP growth rate and the changing struc- ture of the economy during 1980–2013 resulted in a significant growth in energy consumption, though with little apparent impact on the primary energy mix, with coal and oil dominating at unchanged levels. Despite growth in energy consump- tion, India’s primary energy consumption per capita remains low as compared to the world averages. Industrialization, urbanization, and the energy mix are key factors that will influence growth in India’s energy demand. Going forward, India’s primary energy consumption is expected to grow at a rate outpacing China’s. Coal will continue to dominate the energy mix, though it will lose some market share to gas and renewables. India’s energy and emission intensities have declined over time but mostly due to improving energy efficiency and not due to a change in the energy mix. With the energy mix not changing, the gains from greater shares of more energy- and carbon-efficient fuels are likely to remain limited. Significantly for India, domestic production has been sluggish in responding to energy demand growth, and imports are likely to continue rising, placing a significant burden on the macro economy. A higher GDP growth path and a green growth path are explored to understand their implications for the energy policy environment, improvements in energy and carbon intensities, import dependency, and domestic production. -

Indian Renewable Energy Status Report Background Report for DIREC 2010

Indian Renewable Energy Status Report Background Report for DIREC 2010 NREL/TP-6A20-48948 October 2010 D. S. Arora (IRADe) | Sarah Busche (NREL) | Shannon Cowlin (NREL) | Tobias Engelmeier (Bridge to India Pvt. Ltd.) | Hanna Jaritz (IRADe) | Anelia Milbrandt (NREL) | Shannon Wang (REN21 Secretariat) I RADe NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. Available electronically at http://www.osti.gov/bridge Available for a processing fee to U.S. Department of Energy and its contractors, in paper, from: U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information P.O. Box 62 Oak Ridge, TN 37831-0062 phone: 865.576.8401 fax: 865.576.5728 email: mailto:[email protected] Available for sale to the public, in paper, from: U.S. -

Electricity and Natural Gas in India: an Opportunity for India’S National Oil Companies

Do Not Delete 5/21/15 1:28 PM ELECTRICITY AND NATURAL GAS IN INDIA: AN OPPORTUNITY FOR INDIA’S NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES Pierce T. Cox* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 894 II. ELECTRICITY AND ENERGY SECURITY IN INDIA ................. 897 A. Using Coal to Generate Electricity in India .............. 898 B. Alternatives for Generating Electricity in India ....... 900 C. Using Natural Gas to Generate Electricity in India ............................................................................ 904 III. INDIA’S NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES .................................... 908 A. Indian Oil ................................................................... 908 B. Oil and Natural Gas Corporation ............................. 909 C. GAIL Limited .............................................................. 909 IV. CHOOSING SOCIAL POLICY OR ENERGY SECURITY ............. 910 V. THE CHINESE NATIONAL OIL COMPANY MODEL ............... 912 A. Chinese NOCs: Reducing State Influence .................. 913 B. Chinese NOCs: Securing Adequate Supply ............... 915 C. Chinese NOCs: Developing Infrastructure ................ 916 VI. A WAY FORWARD FOR INDIA’S NATIONAL OIL COMPANIES ........................................................................ 917 A. Increased Transparency ............................................. 917 * J.D. Candidate 2015, University of Houston Law Center; B.A. 2007, University of Oklahoma. This Comment received the 2014 Akin Gump Strauss Hauer and Feld Outstanding Comment -

India's Civil Nuclear Power

CAPS In Focus 22 November 2016 www.capsindia.org 123/16 INDIA’S CIVIL NUCLEAR POWER PROGRAMME: A GLIMPSE INTO THE FUTURE Gideon Kharmalki Research Associate, CAPS Civil nuclear energy has always been an India is currently on a path of expanding its civil nuclear power programme on a massive important facet to India’s energy basket. Over the scale, perhaps, second only to China’s ambitions. last ten years, there has been a drastic expansion After years of isolation from the global nuclear in India’s civil nuclear power programme owing commerce, India had a daunting task of to various reasons. First, India is on a path of developing indigenous civil nuclear technology, steady economic growth with its Gross Domestic coupled with a strategy to push for international Product (GDP) consistently rising at a rate of 7- cooperation with the global nuclear commerce. 8%. 1 The common discourse on a country’s Recent trends have also indicated that India is economic growth is its correlation to energy becoming a leader in the closed Nuclear Fuel requirements. The basic assumption is that the Cycle.3 To summarise, India has developed an rate of economic growth is directly proportional innovative closed nuclear fuel cycle, which uses a to the growth of energy requirements. Second, three-stage Nuclear Power Programme. The first global warming and drastic climatic changes stage involves the using of indigenous uranium have created a global resurgence for a more in Pressurised Heavy Water Reactors (PWHRs), immediate need of clean sources of energy. which produces energy and also fissile According to a World Resources Institute report, plutonium as by-product.