Fragmenting Modernism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big History: a Working Bibliography of References, Films & Internet Sites

Big History: A Working Bibliography of References, Films & Internet Sites Assembled by Barry Rodrigue & Daniel Stasko University of Southern Maine (USA) Index Books & Articles on Big History…………………………………………...2–9 Works that Anticipated Big History……………………………………....10–11 Works on Aspects of Big History…………………………………………12–36 Cosmology & Planetary Studies…………. 12–14 Physical Sciences………………………… 14–15 Earth & Atmospheric Sciences…………… 15–16 Life Sciences…………………………….. 16–20 Ecology…………………………………... 20–21 Human Social Sciences…………………… 21–33 Economics, Technology & Energy……….. 33–34 Historiography……………………………. 34–36 Philosophy……………………………….... 36 Popular Journalism………………………... 36 Creative Writing………………………….. 36 Internet & Fim Resources on Big History………………………………… 37–38 1 Books & Articles about Big History Adams, Fred; Greg Laughlin. 1999. The Five Ages of the Universe: Inside the Physics of Eternity. New York: The Free Press. Alvarez, Walter; P. Claeys, and A. Montanari. 2009. “Time-Scale Construction and Periodizing in Big History: From the Eocene-Oligocene Boundary to All of the Past.” Geological Society of America, Special Paper # 452: 1–15. Ashrafi, Babak. 2007. “Big History?” Positioning the History of Science, pp. 7–11, Kostas Gavroglu and Jürgen Renn (editors). Dordrecht: Springer. Asimov, Isaac. 1987. Beginnings: The Story of Origins of Mankind, Life, the Earth, the Universe. New York, Berkeley Books. Aunger, Robert. 2007. “Major Transitions in “Big’ History.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74 (8): 1137–1163. —2007. “A Rigorous Periodization of ‘Big’ History.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74 (8): 1164–1178. Benjamin, Craig. 2004. “Beginnings and Endings” (Chapter 5). Palgrave Advances: World History, pp. 90–111, M. Hughes-Warrington (editor). London and New York: Palgrave/Macmillan. —2009. “The Convergence of Logic, Faith and Values in the Modern Creation Myth.” Evolutionary Epic: Science’s Story and Humanity’s Response, C. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

Singphoniker”

New York Debut of German Vocal Ensemble “Singphoniker” Highlights Include a Tribute to the Legendary “Comedian Harmonists” of Weimer Germany In recent decades no other German vocal ensemble of its kind has enjoyed the success afforded to Singphoniker, which makes its New York debut at The Frick Collection on Sunday, February 7, 1999 at 5:00pm One of the most anticipated events in the 60th season of The Frick Collection’s Chamber Music Series, this program reveals the range of this talented group, featuring selections by Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828), Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856), Felix Mendelssohn (1809 – 1847), as well as a set of songs called Berliner Requiem written by Bertoldt Brecht and set to music by popular composer Kurt Weill (1900 – 1950). Reflective of the rich social turmoil in Germany that followed World War I, Berliner Requiem was composed in 1928 and addresses in six selections a range of issues from the economic crisis to growing anti-Semitism. Particularly capturing the imagination of this “sold-out” audience is a tribute to the legendary Comedian Harmonists, the wildly popular vocal group that flourished in Germany before the Nazis forced them to disband in 1934. The original a cappella ensemble is the subject of a movie “Harmonists” that opened the Jewish Film Festival this month and was reviewed by Peter Gay in The New York Times on January 10, 1999. The Comedian Harmonists performed to adoring audiences in Weimar Germany, charming them with lyrics that provided “a clever mixture of schmalz and suggestiveness.” While the original Comedian Harmonists — a virtual cult phenomenon — left behind several treasured recordings of their music, this event at The Frick Collection offers Americans their first sense of what it was like to experience the group live. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Education of The

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Education of the Senses (The Bourgeois Experience Victoria to Freud #1) by Peter Gay Education of the Senses (The Bourgeois Experience: Victoria to Freud #1) by Peter Gay. PEP-Web Tip of the Day. If you get a large number of results after searching for an article by a specific author, you can refine your search by adding the author’s first initial. For example, try writing “Freud, S.” in the Author box of the Search Tool. For the complete list of tips, see PEP-Web Tips on the PEP-Web support page. Welcome to PEP Web! Viewing the full text of this document requires a subscription to PEP Web. If you are coming in from a university from a registered IP address or secure referral page you should not need to log in. Contact your university librarian in the event of problems. If you have a personal subscription on your own account or through a Society or Institute please put your username and password in the box below. Any difficulties should be reported to your group administrator. Can't remember your username and/or password? If you have forgotten your username and/or password please click here. Once there, click the 'Forgotten Username/Password' button, fill in your email address (this must be the email address that PEP has on record for you) and click "Send." If this does not work for you please click here for customer support information. OpenAthens or federation user? Login here. ( 1987 ). Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association , 35 : 249-254. -

No. 26 Jonathan Israel, Radical Enlightenment

H-France Review Volume 2 (2002) Page 105 H-France Review Vol. 2 (February, 2002), No. 26 Jonathan Israel, Radical Enlightenment: Philosophy and the Making of Modernity, 1650-1750. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. xxii + 810 pp. Maps, tables, plates, notes, bibliography, and index. $45.00 US (cl). ISBN 0-19-820608-9. Review by J.B. Shank, University of Minnesota. Was ist Aufklärung? Robert Darnton recently began a lecture on this topic by asking his audience to repeat the question, only this time with feeling. Jonathan Israel would not have been amused. He finds nothing tired or stale about this classic question of European intellectual history, nor does he see any problem with the classic "men and ideas" approach to it that Darnton has built a career critiquing. Radical Enlightenment, Israel's magisterial history of the emergence of Enlightenment thought in Europe, is nothing if not a throwback to a bygone era when, to borrow from Darnton again, intellectual historians were scholars who took dusty philosophical tomes off library shelves and taught readers how to link them together. Yet despite its frustrating traditionalism and maddening dismissal of an entire generation of newer Enlightenment scholarship, Radical Enlightenment is an important book. It especially offers an important chronological and geographical reconceptualization of the origins of the Enlightenment that scholars, whatever their historiographical stripe, will ignore only at their peril. But will anyone actually read the book? And can the honest reviewer actually recommend that one do so? It is not that Israel is a bad writer. Quite the contrary, he proves to be a very engaging guide to the many topics he presents. -

Bibliography

Darwin‟s Pious Idea: Why the Ultra-Darwinists and Creationists Both Get It Wrong Conor Cunningham Bibliography Abbreviations Saint Thomas Aquinas Comp. Theol. Compendium Theologiae De Malo Quaestio disputata de malo De Pot. Quaestio disputata de potentia De Ver. Quaestio disputata de veritate In II Sent. Scriptum super libros Sententiarum Liber II In III Sent. Scriptum super libros Sententiarium Liber III In II Phys. Sententia super Physicam Liber II Joh. Expositio in evangelium Joannis ScG Summa contra Gentiles STh Summa Theologiae Works Cited Ahouse, Jeremy C. ―The Tragedy of a priori Selectionism: Dennett and Gould on Adaptationism.‖ Biology and Philosophy 13, no. 3 (1998): 359-91. Alexander, Denis, and Robert White. Beyond Belief: Science, Faith and Ethical Challenges. Oxford: Lion Hudson Press, 2004. Alexander, Richard D. The Biology of Moral Systems. Chicago: Aldine de Gruyter, 1987. _____. ―The Search for a General Theory of Behaviour.‖ Behavioural Science 20 (1975): 77- 100. Alroy, John. ―Cope‘s Rule and the Dynamics of Body Mass Evolution in North American Mammals.‖ Science 280 (1998): 731-4. Alter, Torin. ―Phenomenal Knowledge Without Experience.‖ In The Case for Qualia, edited by Edmond Wright, pp. 247-68. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008. Alter, Torin, and Sven Walter, eds. Phenomenal Concepts and Phenomenal Knowledge: New Essays on Consciousness and Physicalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. American Association for the Advancement of Science. ―Board Resolution on Intelligent Design Theory.‖ (October 18, 2002); available online: http://www.aaas.org/news/releases/2002/1106id2.shtml; accessed October 12, 2009. Amundson, Ron. ―Adaptation and Development: On the Lack of Common Ground.‖ In Adaptationism and Optimality, edited by Steven Orzack and Elliott Sober, pp. -

September-2015

Clio’s Psyche Understanding the “Why” of Culture, Current Events, History, and Society Psychohistory at the Crossroads Symposium The Past, Present, and Future of Psychohistory The Baltimore Riots Freud’s Analysis of His Daughter The Ordeal of Alfred Dreyfus Memorials: Peter Gay and Eli Sagan Psychohistory Meeting Reports Volume 22 Numbers 1-2 June-September 2015 Clio’s Psyche Vol. 22 No. 1-2 June-Sept 2015 ISSN 1080-2622 Published Quarterly by the Psychohistory Forum 627 Dakota Trail, Franklin Lakes, NJ 07417 Telephone: (201) 891-7486 E-mail: [email protected] Editor: Paul H. Elovitz Book Review Editor: Ken Fuchsman Editorial Board Herb Barry, PhD University of Pittsburgh • C. Fred Alford, PhD University of Maryland • James W. Anderson, PhD Northwestern University • David Beisel, PhD RCC-SUNY • Donald L. Carveth, PhD, York University • Ken Fuchsman, EdD University of Connecticut • Bob Lentz • Peter Loewenberg, PhD UCLA • Peter Petschauer, PhD Appalachian State University Subscription Rate: Free to members of the Psychohistory Forum $72 two-year subscription to non-members $65 yearly to institutions (Add $60 per year outside U.S.A. & Canada) Single issue price: $21 We welcome articles of psychohistorical interest of 500 - 1,500 words and a few longer ones. Copyright © 2015 The Psychohistory Forum Psychohistory at the Crossroads Symposium The Past, Present, and Future of Psychohistory The Baltimore Riots Freud’s Analysis of His Daughter The Ordeal of Alfred Dreyfus Memorials: Peter Gay and Eli Sagan Psychohistory Meeting Reports Volume 22 Numbers 1-2 June-September 2015 Clio’s Psyche Understanding the “Why” of Culture, Current Events, History, and Society Volume 22 Number 1-2 June-Sept 2015 _____________________________________________________________________ Psychohistory at the Crossroads Symposium Psychohistory Is an Approach Rather than a Discipline. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction In the academic as well as the popular imagination, the Enlighten ment figures as a quintessentially secular phenomenon—indeed, as the very source of modern secular culture. Historical scholarship of the 1960s successfully disseminated this image by propagating the master narrative of a secular Europe an culture that commenced with the Enlightenment.1 This master narrative was the counterpart to modernization theory in the social sciences. The two shared a trium phalist linear teleology: in the social sciences, the destination was ur ban, industrial, democratic society; in intellectual history, it was secu larization and the ascendancy of reason.2 A wide range of philosophers, working from diverse and often conflicting positions, reinforced this image. The Frankfurt School and Alasdair MacIntyre, Foucault and the post-modernists all spoke of a unitary Enlightenment project that, for better or worse, was the unquestionable seedbed of secular culture.3 Open the pages of virtually any academic journal in the humanities today and you will find writers routinely invoking the cliché of a unitary Enlightenment, sometimes as a pejorative, some times as an ideal, but invariably as the starting point of secular mo dernity and rationality. In recent decades this image of a unitary, secular Enlightenment project has become a foundational myth of the United States: it has con verged with the idea of America’s “exceptionalism,” or singular place in the world. Henry Steele Commager argued that whereas Europe 1 Peter Gay, The Enlightenment, 2 vols. -

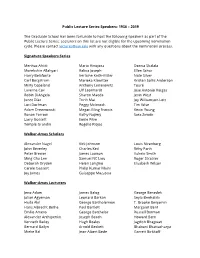

Public Lecture Series Speakers: 1936 – 2019

Public Lecture Series Speakers: 1936 – 2019 The Graduate School has been fortunate to host the following speakers as part of the Public Lecture Series. Lecturers on this list are not eligible for the upcoming nomination cycle. Please contact [email protected] with any questions about the nomination process. Signature Speakers Series Menhaz Afridi Maria Hinojosa Donna Shalala Morehshin Allahyari Ralina Joseph Ellen Schur Harry Belafonte Verlaine Keith-Miller Nate Silver Carl Bergstrom Marieka Klawitter Kristen Soltis Anderson Misty Copeland Anthony Leiserowitz Touré Laverne Cox Ulf Leonhardt Jose Antonio Vargas Robin DiAngelo Sharon Maeda Jevin West Junot Díaz Trinh Mai Joy Williamson-Lott Lori Dorfman Peggy McIntosh Tim Wise Adam Drewnowski Megan Ming Francis Kevin Young Ronan Farrow Kathy Najimy Sara Zewde Larry Gossett Emile Pitre Temple Grandin Rogelio Riojas Walker-Ames Scholars Alexander Nagel Kirk Johnson Louis Nirenberg John Beverley Charles Keil Rithy Panh Peter Brewer James Lawson Valerie Smith Ming Cho Lee Samuel NC Lieu Roger Strasser Deborah Dryden Helen Longino Elizabeth Wilson Carole Gassert Philip Kumar Maini Joy James Guiseppe Mazzotta Walker-Ames Lecturers Jeno Adam James Balog George Benedek Julian Agyeman Leonard Barkan Seyla Benhabib Huda Akil George Bartholemew T. Brooke Benjamin Hans Albrecht Bethe Paul Bartlett Margaret Bent Emilio Amero George Batchelor Russell Berman Alexander Archipenko Joseph Beach Howard Bern Kenneth Bailey Hugh Beales Jagdish Bhagwati Bernard Bailyn Arnold Beckett Bhabani Bhattacharya Mieke Bal Jean-Albert Bede Garrett Birkhoff Alan Bittles Alfred Chandler, Jr. Robert Dicke J. Bjerknes Li Chi Liselotte Dieckmann Felix Bloch Brock Chisholm Jean Dieudonne Bruce Blumberg Gustave Choquet Andrea (Andy) DiSessa Larry Bobo Ralph Cicerone Stuart Dodd Christoph Bode Marion Clawson Denis Donoghue Bart Bok Cornell Clayton Sterling Dow Bert Bolin William Clebsch Curt Ducasse Paul Bonifas JM Coetzee John Dunning Gabriel Bonno Philip Cohen J. -

MEMORIAL Peter Gay (1923–2015)

Central European History 49 (2016), 4–18. © Central European History Society of the American Historical Association, 2016 doi:10.1017/S000893891600008X MEMORIAL Peter Gay (1923–2015) ETER Gay died in Manhattan on May 12, 2015. A professor at Columbia and Yale, Gay was one of the preeminent cultural and intellectual historians of his generation. His Penormous output of scholarship, on subjects as varied as Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Sigmund Freud, Victorian sexuality and modernist art, testifies to the range of his erudition and his restless urge to make his views known. He was the recipient of numerous awards, honorary doctorates, and other distinctions, including the National Book Award in 1967 for The Enlightenment: An Interpretation, the Gold Medal of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1996, and the Geschwister-Scholl-Preis in 1999. After retiring from Yale he became the founding Director of the New York Public Library’s Center for Scholars and Writers, a post he held from 1997 to 2003. He remained extraordinarily productive as a scholar well into his eighties, publishing essays, articles, and books, including a massive history of modernism. His final book, Why the Romantics Matter, appeared last year. Peter Joachim Fröhlich was born into a secularized Jewish family in Berlin in 1923. His father co-owned a firm that arranged for the manufacture of inexpensive versions of high-end porcelain and glassware, which were then sold in department stores and specialty shops. Described by Gay as a “self-made man,” Moritz Fröhlich was born in 1894 in the predom- inantly Polish village of Podjanze in Upper Silesia and received only an eighth-grade educa- tion before embarking on a business career.1 Despite his middle-class standing, Gay’s father was a lifelong supporter of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and a pronounced secularist, views he passed onto his son. -

Radical, Sceptical and Liberal Enlightenment

Journal of the Philosophy of History 14 (2020) 257–283 brill.com/jph Radical, Sceptical and Liberal Enlightenment James Alexander Assistant Professor, Faculty of Economics, Administrative, and Social Sciences, Dept. of Political Science, Bilkent University, Ankara, Turkey [email protected] Abstract We still ask the question ‘What is Enlightenment?’ Every generation seems to offer new and contradictory answers to the question. In the last thirty or so years, the most interesting characterisations of Enlightenment have been by historians. They have told us that there is one Enlightenment, that there are two Enlightenments, that there are many Enlightenments. This has thrown up a second question, ‘How Many Enlightenments?’ In the spirit of collaboration and criticism, I answer both questions by arguing in this article that there are in fact three Enlightenments: Radical, Sceptical and Liberal. These are abstracted from the rival theories of Enlightenment found in the writings of the historians Jonathan Israel, John Robertson and J.G.A. Pocock. Each form of Enlightenment is political; each involves an attitude to history; each takes a view of religion. They are arranged in a sequence of increasing sensitivity to history, as it is this which makes it possible to relate them to each other and indeed propose a composite definition of Enlightenment. The argument should be of interest to anyone concerned with ‘the Enlightenment’ as a historical phenomenon or with ‘Enlightenment’ as a philosophical abstraction. Keywords Radical Enlightenment – Sceptical Enlightenment – Liberal Enlightenment – Jonathan Israel – John Robertson – J.G.A. Pocock 1 Introduction Let me begin with a general claim. There are three ways one can write the history of ideas. -

Science, Psychoanalysis, and the Brain

Science, Psychoanalysis, and the Brain SPACE FOR DIALOGUE Shimon Marom Technion – Israel Institute of Technology 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning, and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107101180 © Shimon Marom 2015 Tis publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2015 Printed in the United States of America A catalog record for this publication is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Marom, Shimon, 1958– Science, psychoanalysis, and the brain : space for dialogue / Shimon Marom. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-107-10118-0 (hardback) 1. Psychoanalysis. 2. Psychoanalysis – Physiological aspects. 3. Psychobiology. 4. Psychophysiology. I. Title. BF175.M28348 2015 150.19′5–dc23 2014043440 ISBN 978-1-107-10118-0 Hardback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet Web sites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such Web sites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. To Adi, by way of a long letter. For a hundred and ffy years past the progress of science has seemed to mean the enlargement of the material universe and the diminu- tion of man’s importance.