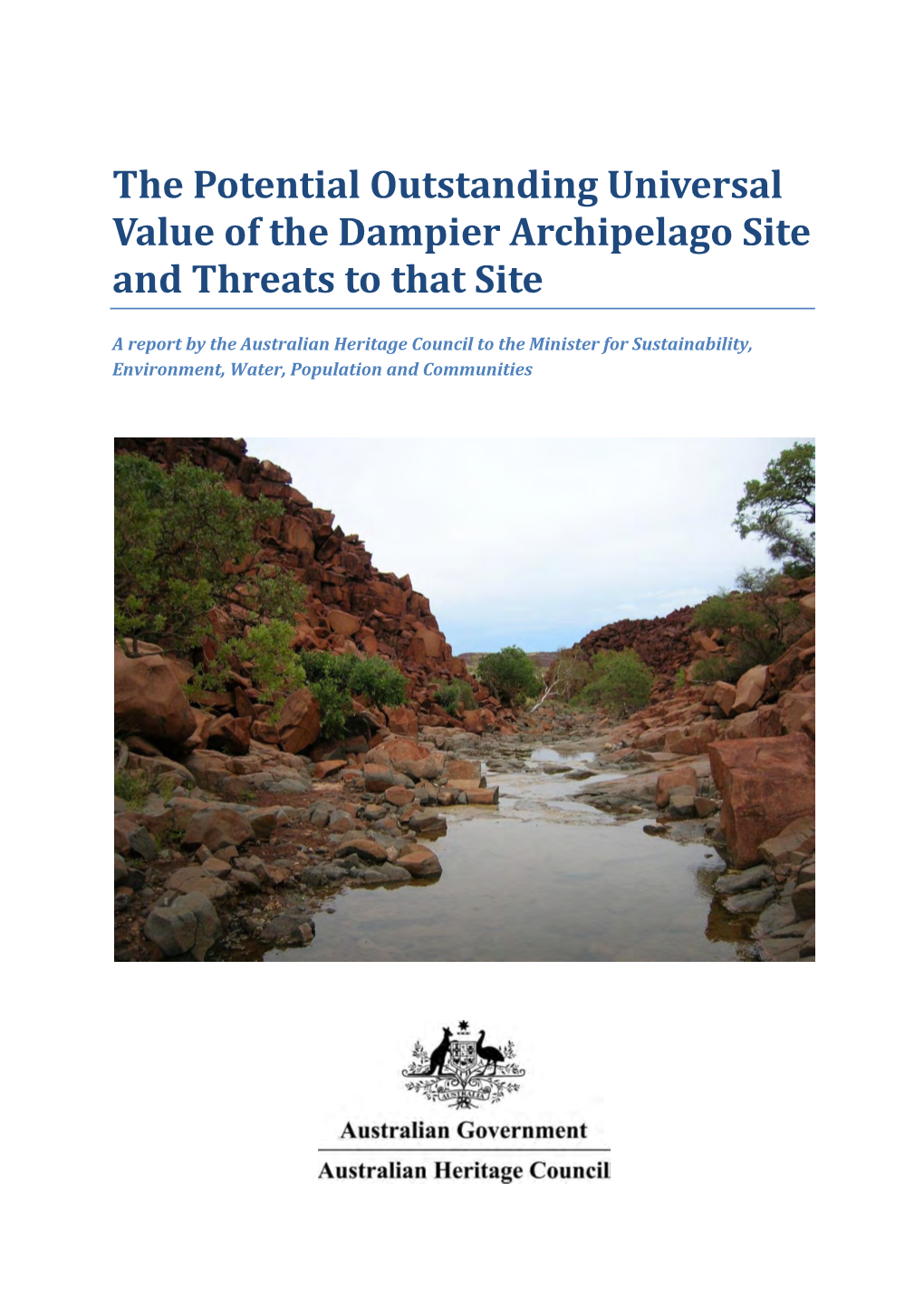

The Potential Outstanding Universal Value of the Dampier Archipelago Site and Threats to That Site

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Archaeology and Rock Art in the Dampier Archipelago

A review of archaeology and rock art in the Dampier Archipelago A report prepared for the National Trust of Australia (WA) Caroline Bird and Sylvia J. Hallam September 2006 Final draft Forward As this thoughtful and readable survey makes clear, the Burrup Peninsula and adjacent islands merit consideration as an integrated cultural landscape. Instead, the Western Australian government is sacrificing it to proclaimed industrial necessity that could have been located in a less destructive area. Before being systematically recorded, this ancient art province is divided in piecemeal fashion. Consequently, sites that are not destroyed by development become forlorn islands in an industrial complex. Twenty-five years ago the Australian Heritage Commission already had noted the region’s potential for World Heritage nomination. Today, State and corporate authorities lobby to prevent its listing even as a National Heritage place! This is shameful treatment for an area containing perhaps the densest concentration of engraved motifs in the world. The fact that even today individual motifs are estimated vaguely to number between 500,000 and one million reflects the scandalous government failure to sponsor an exhaustive survey before planned industrial expansion. It is best described as officially sanctioned cultural vandalism, impacting upon both Indigenous values and an irreplaceable heritage for all Australians. Instead of assigning conservation priorities, since 1980 more than 1800 massive engraved rocks have been wrenched from their context and sited close to a fertilizer plant. The massive gas complex, its expansion approved, sits less than a kilometre from a unique, deeply weathered engraved panel, certainly one of Australia’s most significant ancient art survivors. -

Annual Australian Notices to Mariners Dated 1 January 2013 Is Cancelled and Should Be Destroyed)

ANNUAL AUSTRALIAN NOTICES TO MARINERS IN FORCE ON 1 JANUARY 2014 (Former Annual Australian Notices to Mariners dated 1 January 2013 is cancelled and should be destroyed) Containing Notices Numbers 1-26 and Temporary and Preliminary Notices in force The last Australian Notice to Mariners issued in 2013 was No 1297 IMPORTANT NOTICE This publication includes all significant and relevant information obtained by the Australian Hydrographic Service (AHS) at date of publication. Significant infromation is updated by fortnightly Australian Notices to Mariners. All reasonable efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the information, including third party information, incorporated in this product. The AHS regards third parties from which it receives infrormation as reliable, however the AHS cannot verify all such information and errors may therefore exist. The AHS does not accept liability for errors in third party information or the inappropriate use of this publication. © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process, adapted, communicated or commercially exploited without prior written permission from The Commonwealth represented by the Australian Hydrographic Service. Copyright in some of the material in this publication may be owned by another party and permission for the reproduction of that material must be obtained from the owner. Notices may be copied for the purpose of inserting Notice substance on official charts and publications. Paper copies may be printed by chart agents and distributed to customers on a cost recovery basis. Participating chart agents are listed on the AHS website (www.hydro.gov.au/prodserv/distributors/distributors.htm) and in Chapter 2 of this Annual Notice as providing a 'Paper Notices to Mariners’ service. -

Million Tonnes of Cargo Moved Across Australian Wharves

STATISTICAL REPORT STATISTICAL STATISTICAL REPORT Australian sea freight 2013–14 www.bitre.gov.au Maritime bitre Australianbitre sea freight 2013–14 ISBN 978-1-925216-91-2 Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics Statistical report Australian sea freight 2013–14 Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development Canberra, Australia © Commonwealth of Australia 2015 ISSN: 192 126 0076 ISBN: 978-1-925216-91-2 September 2015/INFRA 2630 Cover photo: Newcastle Port Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia (referred to below as the Commonwealth). Disclaimer The material contained in this publication is made available on the understanding that the Commonwealth is not providing professional advice, and that users exercise their own skill and care with respect to its use, and seek independent advice if necessary. The Commonwealth makes no representations or warranties as to the contents or accuracy of the information contained in this publication. To the extent permitted by law, the Commonwealth disclaims liability to any person or organisation in respect of anything done, or omitted to be done, in reliance upon information contained in this publication. Creative Commons licence With the exception of (a) the Coat of Arms; and (b) the Department of Infrastructure and Transport’s photos and graphics, copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, communicate and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work to the Commonwealth and abide by the other licence terms. -

Special Issue3.7 MB

Volume Eleven Conservation Science 2016 Western Australia Review and synthesis of knowledge of insular ecology, with emphasis on the islands of Western Australia IAN ABBOTT and ALLAN WILLS i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION 2 METHODS 17 Data sources 17 Personal knowledge 17 Assumptions 17 Nomenclatural conventions 17 PRELIMINARY 18 Concepts and definitions 18 Island nomenclature 18 Scope 20 INSULAR FEATURES AND THE ISLAND SYNDROME 20 Physical description 20 Biological description 23 Reduced species richness 23 Occurrence of endemic species or subspecies 23 Occurrence of unique ecosystems 27 Species characteristic of WA islands 27 Hyperabundance 30 Habitat changes 31 Behavioural changes 32 Morphological changes 33 Changes in niches 35 Genetic changes 35 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 36 Degree of exposure to wave action and salt spray 36 Normal exposure 36 Extreme exposure and tidal surge 40 Substrate 41 Topographic variation 42 Maximum elevation 43 Climate 44 Number and extent of vegetation and other types of habitat present 45 Degree of isolation from the nearest source area 49 History: Time since separation (or formation) 52 Planar area 54 Presence of breeding seals, seabirds, and turtles 59 Presence of Indigenous people 60 Activities of Europeans 63 Sampling completeness and comparability 81 Ecological interactions 83 Coups de foudres 94 LINKAGES BETWEEN THE 15 FACTORS 94 ii THE TRANSITION FROM MAINLAND TO ISLAND: KNOWNS; KNOWN UNKNOWNS; AND UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS 96 SPECIES TURNOVER 99 Landbird species 100 Seabird species 108 Waterbird -

Of the Nineteenth-Century Maloti- Drakensberg Mountains1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery The ‘Interior World’ of the Nineteenth-Century Maloti- Drakensberg Mountains1 Rachel King*1, 2, 3 and Sam Challis3 1 Centre of African Studies, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom 2 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom 3 Rock Art Research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Over the last four decades archaeological and historical research has the Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains as a refuge for Bushmen as the nineteenth-century colonial frontier constricted their lifeways and movements. Recent research has expanded on this characterisation of mountains-as-refugia, focusing on ethnically heterogeneous raiding bands (including San) forging new cultural identities in this marginal context. Here, we propose another view of the Maloti-Drakensberg: a dynamic political theatre in which polities that engaged in illicit activities like raiding set the terms of colonial encounters. We employ the concept of landscape friction to re-cast the environmentally marginal Maloti-Drakensberg as a region that fostered the growth of heterodox cultural, subsistence, and political behaviours. We introduce historical, rock art, and ‘dirt’ archaeological evidence and synthesise earlier research to illustrate the significance of the Maloti-Drakensberg during the colonial period. We offer a revised southeast-African colonial landscape and directions for future research. Keywords Maloti-Drakensberg, Basutoland, AmaTola, BaPhuthi, creolisation, interior world 1 We thank Lara Mallen, Mark McGranaghan, Peter Mitchell, and John Wright for comments on this paper. This research was supported by grants from the South African National Research Foundation’s African Origins Platform, a Clarendon Scholarship from the University of Oxford, the Claude Leon Foundation, and the Smuts Memorial Fund at Cambridge. -

Murujuga National Park Brochure

RECYCLE Please return unwanted brochures to distribution points. distribution to brochures unwanted return Please This document is available in alternative formats on request. on formats alternative in available is document This Photo – Kerri Morris/Parks and Wildlife and Morris/Parks Kerri – Photo Above Wildlife and 1080 bait training. training. bait 1080 20140778-0215-2M 2015. February at current Information Photo – Eleanor Killen/Parks Killen/Parks Eleanor – Photo Top Mangroves on the eastern coast of Murujuga. Murujuga. of coast eastern the on Mangroves Visitor guide Visitor Photo – Laurina Bullen/Parks and Wildlife and Bullen/Parks Laurina – Photo Cover bottom bottom Cover beach. Peninsula Burrup North-west Cover top top Cover sign. Park National Murujuga with Rangers Murujuga parks.dpaw.wa.gov.au/park/dampier-archipelago parks.dpaw.wa.gov.au/park/murujuga Online resources: Online Emergencies – call Triple Zero ‘000’ ‘000’ Zero Triple call – Phone: (08) 9183 1248 9183 (08) Phone: Karratha WA 6714 WA Karratha PO Box 1544 Box PO Dampier WA 6713 WA Dampier pilbaracoast.com 18 Minilya crescent Minilya 18 Fax: (08) 9144 4620 9144 (08) Fax: Program (Headquarters) Program Phone: (08) 9144 4600 9144 (08) Phone: Murujuga Ranger Murujuga Karratha WA 6714 WA Karratha murujuga.org.au Lot 4548 Karratha Road Karratha 4548 Lot Email: [email protected] Email: Karratha Visitor Centre Visitor Karratha Fax: (08) 9183 8130 9183 (08) Fax: daa.wa.gov.au Phone: (08) 9144 4112 9144 (08) Phone: Phone: (08) 9235 8000 9235 (08) Phone: Karratha WA 6714 -

Maritimebitre Australian Sea Freight 2014–15

STATISTICAL REPORT Maritimebitre Australian sea freight 2014–15 Bureau of Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Economics Statistical report Australian sea freight 2014–15 Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development Canberra, Australia © Commonwealth of Australia 2017 ISBN: 978-1-925531-39-8 ISSN: 192 126 0076 April 2017/INFRA 3198 Cover photo: Port Melbourne, Victoria Ownership of intellectual property rights in this publication Unless otherwise noted, copyright (and any other intellectual property rights, if any) in this publication is owned by the Commonwealth of Australia (referred to below as the Commonwealth). Disclaimer The material contained in this publication is made available on the understanding that the Commonwealth is not providing professional advice, and that users exercise their own skill and care with respect to its use, and seek independent advice if necessary. The Commonwealth makes no representations or warranties as to the contents or accuracy of the information contained in this publication. To the extent permitted by law, the Commonwealth disclaims liability to any person or organisation in respect of anything done, or omitted to be done, in reliance upon information contained in this publication. Creative Commons licence With the exception of (a) the Coat of Arms; and (b) the Department of Infrastructure and Transport’s photos and graphics, copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia Licence is a standard form licence agreement that allows you to copy, communicate and adapt this publication provided that you attribute the work to the Commonwealth and abide by the other licence terms. -

Editor's Note

Volume 8: Issue 1 (2021) Editor’s Note CONTENTS Dear ICA Members, Editor’s Note .................. 1 Welcome to 2021! We are now a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, and with vaccines on the market, we are seeing the light at the end Meetings, of the tunnel. Announcements, and Calls for Papers .............. 3 The ICA Interest group will be meeting at this year’s virtual SAA Research Highlights ....... 4 meeting on April 16 from 12-1 PM EDT. Please join us to learn more about the group, get involved, and network with colleagues. All are Lapidary artwork in the welcome! Amerindian Caribbean, a regional, open, online Over the past year, there have been over 1000 new publications in database and GIS ....... 4 81 different journals in our field. In addition, several new books have The La Sagesse been published, four of which are featured in our “Recent Community Publications” section. The quantity and quality of new literature attests to the fact that, despite the pandemic, island and coastal Archaeology Project research is thriving. (LCAP) in Grenada, West Indies ................ 6 As always, please continue to send us your new publications. While Recent Publications ....... 7 we do not rely exclusively on sources sent to us by our members, we usually receive at least one member submission from a journal that Featured New Books: 7 we missed in our biannual literature review. Your submissions help Journals Featuring to provide publicity for your work and assists us in putting together a Recent Island and more thorough bibliography each cycle. Coastal Archaeology Papers: ....................... 8 The last issue of the Current appeared when wildfires and political scandal dominated news headlines, and coastal archaeologists faced New Papers in the reports of accelerating sea level rise. -

Report: Protection of Aboriginal Rock Art of the Burrup Peninsula

Labor Senators' additional comments 1.1 Labor Senators acknowledge that Murujuga, also known as the Burrup Peninsula and Dampier Archipelago, is home to one of the largest and the oldest collections of rock art in the world. 1.2 The petroglyphs document human presence in the area over an estimated 45,000 year timespan—the longest continuous production of rock art in the world. 1.3 It is without doubt that the petroglyphs are of immense and irreplaceable cultural and spiritual significance to Aboriginal people, and are of equally immense national and international archaeological and heritage value. 1.4 Labor Senators sincerely thank the Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation for their participation in this inquiry. The Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation represents the five traditional owner groups: the Ngarluma people, the Mardudhunera people, the Yaburara people, the Yindjibarndi people, and the Wong-Goo-Tt-Oo people. We pay respect to the traditional owners and custodians of Murujuga, their continuing connection to this land, and their right to a place of honour in our constitution and a full and equal share in our nation's future. Community control and direct involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the planning and delivery of programs and services is vital. 1.5 Labor is committed to building a relationship where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities are the architects of their place in Australia and are equal partners with government in the development and implementation of policies that affect their way of life and livelihoods. Land and water are the basis of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander spirituality, law, culture, economy and wellbeing. -

Dampier Port Upgrade to 145 Mtpa Capacity

Dampier Port Increase in Throughput to 145 Mtpa ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION STATEMENT Rev 5 September 2007 Dampier Port Increase in throughput to 145 Mtpa ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION STATEMENT Rev 5 September 2007 Sinclair Knight Merz 7th Floor, Durack Centre 263 Adelaide Terrace PO Box H615 Perth WA 6001 Australia Tel: +61 8 9268 4400 Fax: +61 8 9268 4488 Web: www.skmconsulting.com COPYRIGHT: The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Sinclair Knight Merz Pty Ltd. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Sinclair Knight Merz constitutes an infringement of copyright. LIMITATION: This report has been prepared on behalf of and for the exclusive use of Sinclair Knight Merz Pty Ltd’s Client, and is subject to and issued in connection with the provisions of the agreement between Sinclair Knight Merz and its Client. Sinclair Knight Merz accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for or in respect of any use of or reliance upon this report by any third party. The SKM logo is a trade mark of Sinclair Knight Merz Pty Ltd. © Sinclair Knight Merz Pty Ltd, 2006 Environmental Protection Statement Contents 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 The Proposal 1 1.2.1 Proposal Title 1 1.3 The Proponent 2 1.4 Licensing/Approvals 3 1.5 Current Environmental Approval Process 3 1.5.1 Ministerial Conditions (120 Mtpa) 4 1.5.2 Other Approvals 7 1.6 Project Schedule 8 1.7 Structure of this Document 8 2. Project Justification and Evaluation of Alternatives 11 2.1 Project Justification 11 2.2 Evaluation of Alternatives 11 2.2.1 Development Options beyond 120 Mtpa 11 2.3 No Development Option 12 3. -

Reconciliation Action Plan Report

RELATIONSHIPS RESPECT Enhanced Pilbara Agreements Cultural Awareness Training Woodside expanded its community, heritage and economic With the drive to improve the cultural awareness and competency participation arrangements by signing new agreements with of our workforce, Woodside has introduced a new online cultural the Ngarluma Yindjibarndi Foundation Limited (NYFL), which learning course. The new offering encourages an inclusive culture represents the Ngarluma and Yindjibarndi people, and the for our Indigenous employees across the wider organisation. Murujuga Aboriginal Corporation (MAC), which represents Woodside’s Indigenous employees were actively engaged to the Wong-Goo-Tt-Oo, Ngarluma, Yindjibarndi, Yaburara and guide the development of the content of the online cultural Mardudhunera language groups. learning and its delivery. An Indigenous business founded in the Woodside has operated on the Burrup Peninsula for 35 years, Pilbara was chosen to develop the online training offering. and these agreements demonstrate an ongoing commitment The result is a cultural learning course that aims to widen to the successful co-existence of heritage and industry and perspectives on Indigenous cultures and people through an support for long term, positive outcomes for local exploration of key cultural concepts and an honest telling of the communities. recent history of Indigenous Australians. The training challenges The updated commitment to NYFL includes increased unconscious bias and uses a personal style of storytelling that funding for programs and benefits that are being delivered encourages empathy and understanding of the Indigenous under the existing agreement which was signed in 1998. perspective and experience. Additional support has been made available for capacity The training has received positive feedback from participants and building and social investment programs. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS OF HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING B rief Biographies o f the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 17 5 0 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. i i nsr TWO PARTS. P a r t I .— 1 7 5 0 t o 1 8 3 0 . EASTBOURNE : HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY 8251.70 A ASTOR, LENOX AND TILDEN FOUNDATIONS R 1936 L Digitized by PRE F A CE. ♦ N gathering together, and publishing, brief memoirs of the numerous maritime surveyors of all countries, but chiefly of Great Britain, whose labours, extending over upwards of a century, have contributed the I means or constructing the charted portion óf the world, the author claims no originality. The task has been one of research, compilation, and abridgment, of a pleasant nature, undertaken during leisure evenings, after official hours spent in duties and undertakings of a kindred description. Numerous authorities have been consulted, and in some important instances, freely borrowed from ; amongst which, may be mentioned, former numbers of the Nautical Magazine, the Journals of the Royal Geographical Society, published accounts of voyages, personal memoirs, hydrographic works, the Naval Chronicle, Marshall, and O'Bymes Naval Biographies, &c. The object aimed at has been, to produce in a condensed form, a work, useful for hydrographic reference, and sufficiently matter of fact, for any amongst the naval surveyors of the past, who may care to take it up, for reference—and at the same time,—to handle dry dates and figures, in such a way, as to render such matter, sufficiently light and entertaining, for the present and rising generation of naval officers, who, possessing a taste for similar labours to those enumerated, may elect a hydrographic career.