Suprematist Architecture: a Plane Drawing Architectural History Thesis on Suprematist Architecture by Kazimir Malevich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2

MIT 4.602, Modern Art and Mass Culture (HASS-D) Spring 2004 Professor Caroline A. Jones Lecture Notes History, Theory and Criticism Section, Department of Architecture Week 9, Lecture 2 PHOTOGRAPHY, PROPAGANDA, MONTAGE: Soviet Avant-Garde “We are all primitives of the 20th century” – Ivan Kliun, 1916 UNOVIS members’ aims include the “study of the system of Suprematist projection and the designing of blueprints and plans in accordance with it; ruling off the earth’s expanse into squares, giving each energy cell its place in the overall scheme; organization and accommodation on the earth’s surface of all its intrinsic elements, charting those points and lines out of which the forms of Suprematism will ascend and slip into space.” — Ilya Chashnik , 1921 I. Making “Modern Man” A. Kasimir Malevich – Suprematism 1) Suprematism begins ca. 1913, influenced by Cubo-Futurism 2) Suprematism officially launched, 1915 – manifesto and exhibition titled “0.10 The Last Futurist Exhibition” in Petrograd. B. El (Elazar) Lissitzky 1) “Proun” as utopia 2) Types, and the new modern man C. Modern Woman? 1) Sonia Terk Delaunay in Paris a) “Orphism” or “organic Cubism” 1911 b) “Simultaneous” clothing, ceramics, textiles, cars 1913-20s 2) Natalia Goncharova, “Rayonism” 3) Lyubov Popova, Varvara Stepanova stage designs II. Monuments without Beards -- Vladimir Tatlin A. Constructivism (developed in parallel with Suprematism as sculptural variant) B. Productivism (the tweaking of “l’art pour l’art” to be more socialist) C. Monument to the Third International (Tatlin’s Tower), 1921 III. Collapse of the Avant-Garde? A. 1937 Paris Exposition, 1937 Entartete Kunst, 1939 Popular Front B. -

Photo/Arts MY DEAR MALEVICH (MDM)

TOM R. CHAMBERS - Photo/Arts Highlights from his personal website. Many of the links on the page go back to the website for greater detailing. Tom R. Chambers is a documentary photographer and visual artist, and he is currently working with the pixel as Minimalist Art ("Pixelscapes") and Kazimir Malevich's "Black Square" ("Black Square Interpretations"). He has over 100 exhibitions to his credit. His "My Dear Malevich" project has received international acclaim, and it was shown as a part of the "Suprematism Infinity: Reflections, Interpretations, Explorations" exhibition in conjunction with the "100 Years of Suprematism" conference at Columbia University, New York City (2015). MY DEAR MALEVICH (MDM) "My Dear Malevich" This homage to Kazimir Malevich is a confirmation of Tom R. Chambers' Pixelscapes as Minimalist Art and in keeping with Malevich's Suprematism - the feeling of non-objectivity - the creation of a sense of bliss and wonder via abstraction. Chambers' action of looking within a portrait (photo) of Kazimir Malevich to find the basic component(s), pixel(s) is the same action as Malevich looking within himself - inside the objective world - for a pure feeling in creative art to find his "Black Square", "Black Cross" and other Suprematist works. And there's a mathematical parallel between Malevich's primitive square ("Black Square") ... divided into four, then divided into nine ("Black Cross") ... and Chambers' Pixelscapes. The pixel is the most basic component of any computer graphic, and it can be represented by 1 bit (a 1 if the pixel is black, or a 0 if the pixel is white). And filters (tools [e.g., halftone]) in a graphics program like Photoshop produce changes by mathematically modifying pixel values based on the values of neighboring pixels. -

Else Alfelt, Lotti Van Der Gaag, and Defining Cobra

WAS THE MATTER SETTLED? ELSE ALFELT, LOTTI VAN DER GAAG, AND DEFINING COBRA Kari Boroff A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2020 Committee: Katerina Ruedi Ray, Advisor Mille Guldbeck Andrew Hershberger © 2020 Kari Boroff All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katerina Ruedi Ray, Advisor The CoBrA art movement (1948-1951) stands prominently among the few European avant-garde groups formed in the aftermath of World War II. Emphasizing international collaboration, rejecting the past, and embracing spontaneity and intuition, CoBrA artists created artworks expressing fundamental human creativity. Although the group was dominated by men, a small number of women were associated with CoBrA, two of whom continue to be the subject of debate within CoBrA scholarship to this day: the Danish painter Else Alfelt (1910-1974) and the Dutch sculptor Lotti van der Gaag (1923-1999), known as “Lotti.” In contributing to this debate, I address the work and CoBrA membership status of Alfelt and Lotti by comparing their artworks to CoBrA’s two main manifestoes, texts that together provide the clearest definition of the group’s overall ideas and theories. Alfelt, while recognized as a full CoBrA member, created structured, geometric paintings, influenced by German Expressionism and traditional Japanese art; I thus argue that her work does not fit the group’s formal aesthetic or philosophy. Conversely Lotti, who was never asked to join CoBrA, and was rejected from exhibiting with the group, produced sculptures with rough, intuitive, and childlike forms that clearly do fit CoBrA’s ideas as presented in its two manifestoes. -

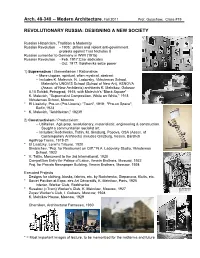

C:\Users\Kai\Documents\CMU Teaching\Modern\Handouts

Arch. 48-340 -- Modern Architecture, Fall 2011 Prof. Gutschow, Class #19 REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA: DESIGNING A NEW SOCIETY Russian Historicism, Tradition & Modernity Russian Revolution - 1905: strikes and violent anti-government protests against Tsar Nicholas II Russian surrender to Germany in WWI (1915) Russian Revolution - Feb. 1917:Czar abdicates - Oct. 1917: Bolsheviks seize power 1) Suprematism / Elementarism / Rationalism -- More utopian, spiritual, often mystical, abstract -- Includes K. Malevich, N. Ladovsky, Vkhutemas School, Malevich's UNOVIS School (School of New Art), ASNOVA (Assoc. of New Architects) architects K. Melnikov, Golosov 0.10 Exhibit, Petrograd, 1915, with Malevich’s “Black Square” K. Malevich, "Suprematist Composition, White on White," 1918 Vkhutemas School, Moscow * El Lissitzky, Pro-un (Pro-Unovis): "Town", 1919; "Pro-un Space", Berlin,1923 * K. Malevich, "Arkhitekton," 1923ff 2) Constructivism / Productivism: -- Utilitarian, Agit-prop, revolutionary, materialistic, engineering & construction. Sought a communitarian socialist art. -- Includes: Rodchenko, Tatlin, M. Ginsburg, Popova, OSA (Assoc. of Contemporary Architects) includes Ginzburg, Vesnin, Barshch AgitProp Trains, 1919-21 * El Lissitzky, Lenin's Tribune, 1920 Simbirchev, “Proj. for Restaurant on Cliff," N.A. Ladovsky Studio, Vkhutemas School, 1922 * V. Tatlin, Monument to the 3rd International, 1920 Competition Entry for Palace of Labor, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1922 Proj. for Pravda Newspaper Building, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1924 Executed Projects Designs for clothing, kiosks, fabrics, etc. by Rodchenko, Stepanova, Klutis, etc. * Soviet Pavilion at Expo. des Art Décoratifs, K. Melnikov, Paris, 1925 Interior, Worker Club, Rodchenko * Rusakov (=Tram) Worker's Club, K. Melnikov, Moscow, 1927 Zuyev Worker's Club, I. Golosov, Moscow, 1928 K. Melnikov House, Moscow, 1929 Chernikov, Architectural Fantasies, 1930 * = Most important images of lecture, to be memorized for the midterms and future . -

Rayonists and Futurists: a Manifesto, 1913

MIKHAIL LARIONOV AND NATALYA GONCHAROVA Rayonists and Futurists: A Manifesto, 1913 For biographies see pp. 79 and 54. The text of this piece, "Luchisty i budushchniki. Manifest," appeared in the miscel- lany Oslinyi kkvost i mishen [Donkey's Tail and Target] (Moscow, July iQn), pp. 9-48 [bibl. R319; it is reprinted in bibl. R14, pp. 175-78. It has been translated into French in bibl. 132, pp. 29-32, and in part, into English in bibl. 45, pp. 124-26]. The declarations are similar to those advanced in the catalogue of the '^Target'.' exhibition held in Moscow in March IQIT fbibl. R315], and the concluding para- graphs are virtually the same as those of Larionov's "Rayonist Painting.'1 Although the theory of rayonist painting was known already, the "Target" acted as tReTormaL demonstration of its practical "acKieveffllBnty' Becau'S^r^ffie^anous allusions to the Knave of Diamonds. "A Slap in the Face of Public Taste," and David Burliuk, this manifesto acts as a polemical гейроп^ ^Х^ШШУ's rivals^ The use of the Russian neologism ШШ^сТиШ?, and not the European borrowing futuristy, betrays Larionov's current rejection of the West and his orientation toward Russian and East- ern cultural traditions. In addition to Larionov and Goncharova, the signers of the manifesto were Timofei Bogomazov (a sergeant-major and amateur painter whom Larionov had befriended during his military service—no relative of the artist Alek- sandr Bogomazov) and the artists Morits Fabri, Ivan Larionov (brother of Mikhail), Mikhail Le-Dantiyu, Vyacheslav Levkievsky, Vladimir Obolensky, Sergei Romano- vich, Aleksandr Shevchenko, and Kirill Zdanevich (brother of Ilya). -

Read Book Kazimir Malevich

KAZIMIR MALEVICH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Achim Borchardt-Hume | 264 pages | 21 Apr 2015 | TATE PUBLISHING | 9781849761468 | English | London, United Kingdom Kazimir Malevich PDF Book From the beginning of the s, modern art was falling out of favor with the new government of Joseph Stalin. Red Cavalry Riding. Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. The movement did have a handful of supporters amongst the Russian avant garde but it was dwarfed by its sibling constructivism whose manifesto harmonized better with the ideological sentiments of the revolutionary communist government during the early days of Soviet Union. What's more, as the writers and abstract pundits were occupied with what constituted writing, Malevich came to be interested by the quest for workmanship's barest basics. Black Square. Woman Torso. The painting's quality has degraded considerably since it was drawn. Guggenheim —an early and passionate collector of the Russian avant-garde—was inspired by the same aesthetic ideals and spiritual quest that exemplified Malevich's art. Hidden categories: Articles with short description Short description matches Wikidata Use dmy dates from May All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from June Lyubov Popova - You might like Left Right. Harvard doctoral candidate Julia Bekman Chadaga writes: "In his later writings, Malevich defined the 'additional element' as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception Retrieved 6 July A white cube decorated with a black square was placed on his tomb. It was one of the most radical improvements in dynamic workmanship. Landscape with a White House. -

Digital Suprematism Overview

DIGITAL SUPREMATISM "Tom R. Chambers is a Texan with a “Russian, Suprematist soul”. He has repeatedly introduced the modern trend of new media art to the masses. He has brought Minimalism to the pixel. In 2000, Chambers began to look at the pixel in the context of Abstraction and Minimalism. And he is currently working with interpretations of Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square” and other Suprematist forms. His work calls our attention to visual singularity, which is all that we see in the digital universe. Since the pixel corresponds to what we call “subatomic particles” in our physical universe, Chambers’ work connects us directly with the feeling of Russian Suprematism, described as the spirit that pervades everything, and pays tribute to the faith in the ability of abstraction to convey “net feeling in the work.” (Curator, OMG [One Month Gallery], Moscow, Russia, 2015) Chambers states: “I have always liked Minimalist works and as a digital artist, I began to explore the pixel as an art form in 2000. As I did research, and experimented with this picture element, I also began to read about Kazimir Malevich and his extreme Minimalist approach with ‘Black Square’. The more I contemplated his ‘Black Square’, the deeper I moved into the pixel and consequently the creation of the ‘My Dear Malevich’ project, which revealed similar to identical Suprematist forms that he created. I have focused on the pixel and his ‘Black Square’ ever since.” My Dear Malevich (MDM) (http://tomrchambers.com/malevich.html) In 2007, Chambers traveled (via magnification) into a digitized photograph of Malevich and discovered at the singular pixel level arrangements which echo back directly to Malevich's own totally abstract compositions. -

The Purge of Modern Trends

PATRICIA RAILING The Purge of Modern Trends Patricia Railing has published widely on the Russian Avant-Garde. She is $IRECTOR OF !RTISTS s "OOKWORKS THAT PUBLISHES REPRINTS OF EARLY TH CENTURY artists’ books and writings, as well as studies on the Russian Avant-Garde. Her Alexandra Exter Paints appeared in October 2011 and her doctoral thesis, Kazimir Malevich – Suprematism as Pure Sensation (Université de Paris 1 – Sorbonne, Philosophy of Art) will soon appear under the title, Malevich Paints – The Seeing Eye. 7KDWWKHDUWVIURPSDLQWLQJWROLWHUDWXUHWRWKHDWUH ³RUJDQLVDWLRQV PLJKW FKDQJH WR EHLQJ DQ LQVWUXPHQW IRU WKH WR PXVLF VKRXOG EH FRQVLGHUHG VR SRZHUIXO WKDW PD[LPXPPRELOLVDWLRQRI6RYLHWZULWHUVDQGDUWLVWVIRUWKHWDVNV 34 WKH\ KDG WR EH VXEYHUWHG WR WKH DXWKRULW\ RI WKH 6WDOLQLVW RIVRFLDOLVWFRQVWUXFWLRQ´1 UHJLPHVD\VPRUHDERXWWKHHIIHFWVRIWKHDUWVRQWKHKXPDQ EHLQJWKDQZRXOGEHDGPLWWHGLQPRGHUQ:HVWHUQVRFLHWLHV 7KXVWKHDUWVFDPHXQGHUWKHIXOOFRQWURORIWKH6WDWHDQGLIQRW )RUWKHPDUWLVXVXVDOO\FRQVLGHUHGDOX[XU\DSOD\WKLQJDQ DFWXDOO\GHVWUR\HGZKLFKVRPHDUWZDVLWFRXOGDWOHDVWEHPDGH LQYHVWPHQWRUVLPSO\LUUHOHYDQW WRFRQIRUPRUWRGLVDSSHDU ,Q5XVVLDIURPWKHVDUWZDVYLWDOEHFDXVHLWVUROH :KDWHYHUFRXOGQRWEHFODVVL¿HGDV³SUROHWDULDW´DQGZKDWHYHU ZDVWRDQQRXQFHDQGFRQYLQFHWKHSRSXODUPDVVHVDERXWWKH FRXOG EH FODVVL¿HG DV ³ERXUJHRLV´ ZHUH XQGHU WKUHDW :KHWKHU QHZ SROLWLFDO UHJLPH7KH SHDVDQW DQG WKH SUROHWDULDW ZHUH )UHQFK,PSUHVVLRQLVP3RVW,PSUHVVLRQLVP)DXYLVPDQG&XELVPRU WREHSHUVXDVLYHO\SRUWUD\HGDQGWKXVDUWEHFDPHWKHWRRO 5XVVLDQ,PSUHVVLRQLVPWR6XSUHPDWLVPDQG&RQVWUXFWLYLVPDOOZHUH IRU SURSDJDQGD &RLQFLGHQWO\ -

Summer Catalogue 2018

www.bookvica.com SUMMER CATALOGUE 2018 1 F O R E W O R D Dear friends and collegues, Bookvica team is excited to present to you the summer catalogue of 2018! The catalogue include some of our usual sections along with new experimental ones. Interesting that many books from our selection explore experiments in different fields like art and science themselves. For example our usual sections of art exhibition catalogues and science include such names as Goncharova and Mendeleev - both were great exepimenters. Theatre section keeps exploring experiments on and off stage of the 1920s under striking constrictivist wrappers. We continue to explore early Soviet period with an important section on art for the masses where we gathered editions which shed light on how Soviets used all available matters to create a new citizen on shatters of the past and how to make him a loyal tool of propaganda. Photography and art of that period is gathered in a separate section with such names like Zdanevich and Telingater among the artists. Books on architecture include Chernikhov fantasies, Stepanova’s design of metro book, study of Soviet workers’ clubs and the most spectacular item is account of the work made by architecture studios in early 1930s led by most famous Russian architects. Probably the jewel of our selection is a rare collection of sheet music from 1920s-30s or more precisely cover designs. We have been gathering them for a year and are happy to finally share our discoveries on this subject with you. Don’t miss too small but very interesting sections of Ukrainian books and items on Women. -

Art 150: Introduction to the Visual Arts David Mccarthy Rhodes College, Spring 2003 414 Clough, Ext

Art 150: Introduction to the Visual Arts David McCarthy Rhodes College, Spring 2003 414 Clough, Ext. 3663 417 Clough, MWF 11:30-12:30 Office Hours: MWF 2:00- 4:00, and by appointment. COURSE OBJECTIVES AND DESCRIPTION The objectives of the course are as follows: (1) to provide students with a comprehensive, theoretical introduction to the visual arts; (2) to develop skills of visual analysis; (3) to examine various media used by artists; (4) to introduce students to methods of interpretation; and (5) to develop skills in writing about art. Throughout the course we will keep in mind the following two statements: Pierre Auguste Renoir’s reminder that, “to practice an art, you must begin with the ABCs of that art;” and E.H. Gombrich’s insight that, “the form of representation cannot be divorced from its purpose and the requirements of the society in which the given language gains currency.” Among the themes and issues we will examine are the following: balance, shape and form, space, color, conventions, signs and symbols, representation, reception, and interpretation. To do this we will look at many different types of art produced in several historical epochs and conceived in a variety of media. Whenever possible we will examine original art objects. Art 150 is a foundation course that serves as an introduction for further work in studio art and art history. A three-hour course, Art 150 satisfies the fine arts requirement. Enrollment is limited to first- and second-year students who are not expected to have had any previous experience with either studio or art history. -

Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: the Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-1922 the Jewish Museum September 14, 2018-January 6, 2019

Chagall, Lissitzky, Malevich: The Russian Avant-Garde in Vitebsk, 1918-1922 The Jewish Museum September 14, 2018-January 6, 2019 Checklist SECOND FLOOR CORRIDOR AND ELEVATOR LOBBY FILM CLIP TO PROJECT ON WALL ACROSS SECOND FLOOR ELEVATOR Chronicle of the Russian Revolution, 1917 32mm film, black-and-white, silent, fifteen-second extract Gaumont Pathé Archives, Saint-Ouen, France GRAPHIC-PHOTO BLOW UP (before entrance to exhibition) Teachers, students, and employees of the Vitebsk People's Art School, Winter 1919-20 Archives Marc et Ida Chagall, Paris Exhibition Gallery 1: KAPLAN GALLERY SECTION 1: POST-REVOLUTIONARY FERVOR IN VITEBSK Marc Chagall (1887–1985) Study for Double portrait with Wine Glass, 1917 Graphite and watercolor on the back of a Cyrillic print, framed dimensions 21 7/8 x 16 15/16 in. (55.5 x 43 cm); 27.8 x 15.6 cm Centre Pompidou, Musée Nationale d’Art Moderne, Paris , donation in lieu of inheritance tax, 1988 Marc Chagall (1887–1985) Double portrait with Wine Glass, [1917-18] Oil on canvas, framed dimensions: 97 ¼ x 58 11/16 in. (247 x 149 cm); 92 ½ x 53 15/16 in. (235 x 137 cm) Centre Pompidou, Musée Nationale d’Art Moderne, Paris, gift of the artist, 1949 David Yakerson (1896–1947) Sketch for the Composition “Panel with the Figure of a Worker,” 1918 Watercolor and ink on paper, framed dimensions: 30 15/16 x 25 in. (78.5 x 63.5 cm) ; 18 ½ x 13 3/8 in. (47 x 34 cm) Vitebsk Regional Museum of Local History David Yakerson (1896–1947) Red Guards, 1918 Watercolor and ink on paper, framed dimensions: 30 15/16 x 25 in.