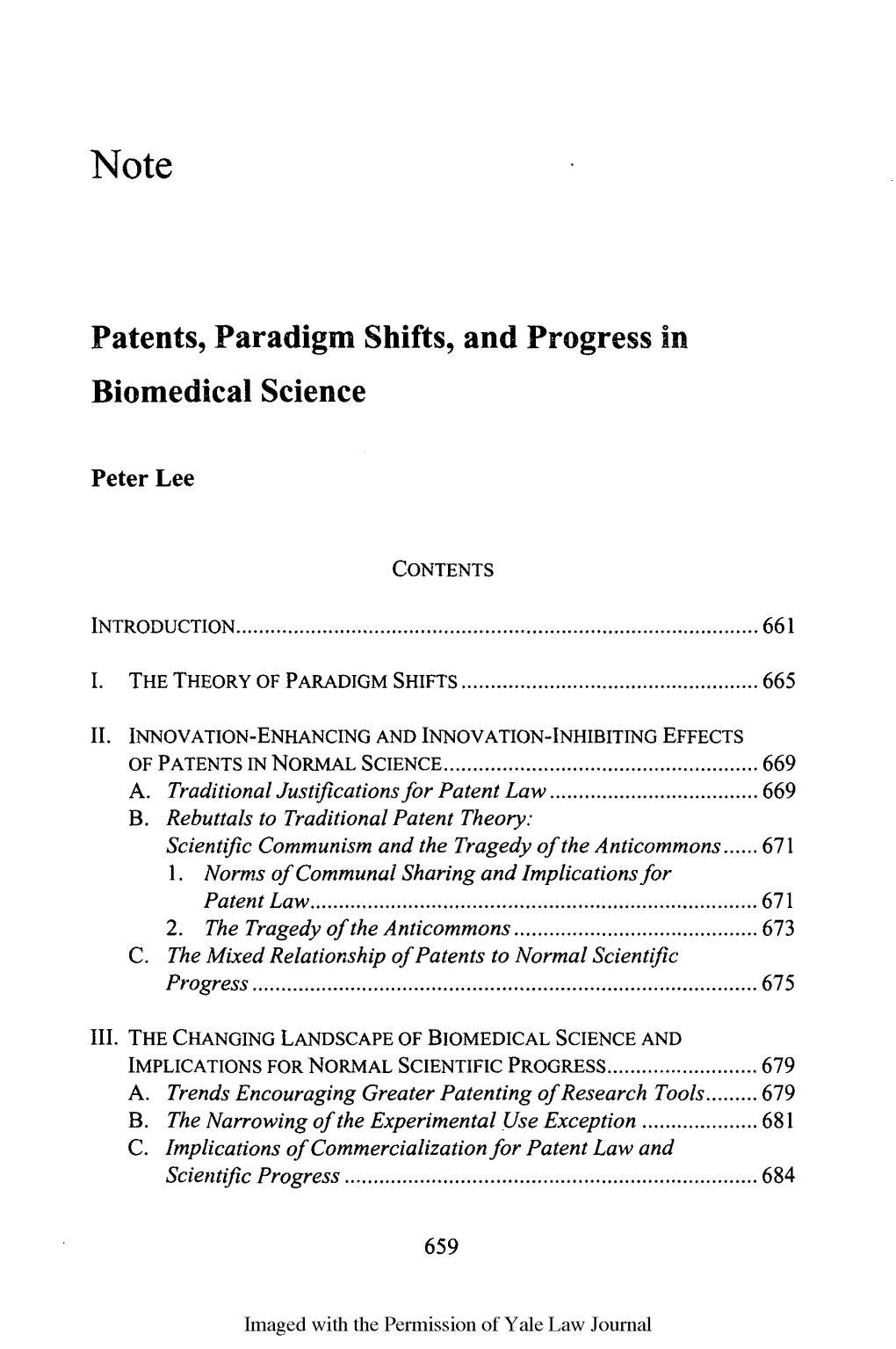

Patents, Paradigm Shifts, and Progress in Biomedical Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Kuhn on Paradigms

Vol. 29, No. 7, July 2020, pp. 1650–1657 DOI 10.1111/poms.13188 ISSN 1059-1478|EISSN 1937-5956|20|2907|1650 © 2020 Production and Operations Management Society Thomas Kuhn on Paradigms Gopesh Anand Department of Business Administration, Gies College of Business, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 469 Wohlers Hall, 1206 South Sixth Street, Champaign, Illinois 61820, USA, [email protected] Eric C. Larson Department of Business Administration, Gies College of Business, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 8 Wohlers Hall, 1206 S. Sixth, Champaign, Illinois 61820, USA, [email protected] Joseph T. Mahoney* Department of Business Administration, Gies College of Business, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 140C Wohlers Hall, 1206 South Sixth Street, Champaign, Illinois 61820, USA, [email protected] his study provides key arguments and contributions of Kuhn (1970) concerning paradigms, paradigm shifts, and sci- T entific revolutions. We provide interpretations of Kuhn’s (1970) key ideas and concepts, especially as they relate to business management research. We conclude by considering the practical implications of paradigms and paradigm shifts for contemporary business management researchers and suggest that ethical rules of conversation are at least as critical for the health of a scientific community as methodological rules (e.g., the rules of logical positivism) derived from the phi- losophy of science. Key words: Paradigms; paradigm shifts; scientific revolutions; normal science History: Received: February 2019; Accepted: March 2020 by Kalyan Singhal, after 3 revisions. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions the rich descriptions of the process of advancing this theory. SSR showed that science primarily advances Thomas S. -

NIEUWE RELEASES KLIK OP DE HOES VOOR DE SINGLE (Mits Beschikbaar)

NIEUWE RELEASES KLIK OP DE HOES VOOR DE SINGLE (mits beschikbaar) LEONARD COHEN – You Want It Darker CD/LP 'You Want It Darker', een paar weken geleden werd deze titeltrack vrijgegeven online en ik was meteen verkocht. Ik vond de vorige plaat 'Populair Problems' al fantastisch maar 'You Want It Darker' overtreft het op alle vlakken. Donkere plaat met veel verwijzingen naar de dood bijvoorbeeld wat op zich niet vreemd is gezien zijn leeftijd (82). Prachtig en ontroerend meesterwerk van deze levende legende! Het wordt druk boven in de top tien albums van het jaar.... KENSINGTON – Control CD/LP ‘Control’ is het nieuwe album van Kensington, het Utrechtse viertal dat zich de afgelopen jaren heeft ontwikkeld tot één van de grootste bands van het land. Niet alleen door het succesvolle album ‘Rivals’ maar ook door hun live reputatie waarmee ze de festival- en live podia (én maar liefst 4x in onze winkel!) hebben veroverd. Eerste single van het album ‘Control’ is ‘Do I Ever’. Het album is gelimiteerd verkrijgbaar als cd digipack inclusief een 20 pagina booklet én op vinyl (eerste oplage is genummerd en gekleurd vinyl). KORN – Serenity of Suffering CD/CD-Deluxe/LP/LP-Deluxe 'Serenity of Suffering' is het 12e studio album van de nu-metal band Korn. Volgens gitarist Brian Welch is deze plaat een stuk zwaarder en steviger dan dat iemand in een lange tijd heeft gehoord. Het album is de opvolger van 'The Paradigm Shift' uit 2013 en werd geproduceerd door Grammy-award winnende producer Nick Raskulinecsz (Foo Fighters, Deftones, Mastodon). Op de deluxe versie staan twee extra tracks. -

PDF Download Starting with Science Strategies for Introducing Young Children to Inquiry 1St Edition Ebook

STARTING WITH SCIENCE STRATEGIES FOR INTRODUCING YOUNG CHILDREN TO INQUIRY 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marcia Talhelm Edson | 9781571108074 | | | | | Starting with Science Strategies for Introducing Young Children to Inquiry 1st edition PDF Book The presentation of the material is as good as the material utilizing star trek analogies, ancient wisdom and literature and so much more. Using Multivariate Statistics. Michael Gramling examines the impact of policy on practice in early childhood education. Part of a series on. Schauble and colleagues , for example, found that fifth grade students designed better experiments after instruction about the purpose of experimentation. For example, some suggest that learning about NoS enables children to understand the tentative and developmental NoS and science as a human activity, which makes science more interesting for children to learn Abd-El-Khalick a ; Driver et al. Research on teaching and learning of nature of science. The authors begin with theory in a cultural context as a foundation. What makes professional development effective? Frequently, the term NoS is utilised when considering matters about science. This book is a documentary account of a young intern who worked in the Reggio system in Italy and how she brought this pedagogy home to her school in St. Taking Science to School answers such questions as:. The content of the inquiries in science in the professional development programme was based on the different strands of the primary science curriculum, namely Living Things, Energy and Forces, Materials and Environmental Awareness and Care DES Exit interview. Begin to address the necessity of understanding other usually peer positions before they can discuss or comment on those positions. -

Evolving Paradigms of Communication Research

International Journal of Communication 7 (2013), Feature 230–238 1932–8036/2013FEA0002 Evolving Paradigms of Communication Research KLAUS BRUHN JENSEN University of Copenhagen W. RUSSELL NEUMAN University of Michigan The MIT historian of science Thomas S. Kuhn famously introduced the notions of paradigm, paradigm shift, and revolutionary science in his Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1970/1962), focusing primarily on the early histories of chemistry and astronomy. Those ideas and the parallel notion of puzzle- solving normal science have become frequently and influentially used in both the social sciences and humanistic scholarship, including the interdisciplinary field of communication research (Bennett & Iyengar, 2010; Dervin et al., 1989; Katz, 1992; Gitlin, 1978; Rosengren, 1985; Wang, 2011). What follows is a continuation and extension of a special section of The International Journal of Communication on the topic, “Communication Research as a Discipline.” Reflecting on the future of the field, the present special section joins contributions from a collection of key European scholars around a focus on three interrelated questions: 1. Is it useful and appropriate to characterize the diverse practices of communication research as reflecting an underlying paradigm or paradigms which represent the common concerns of a community of scholars? 2. To the extent that the notion of paradigms is a legacy of past communication research, is this legacy subject to pressures to change as a result of the significant transformations in the media technologies of the digital age? 3. Similarly, are past paradigms subject to pressures to change as a result of new historical conditions, public practices of communication, and normative concerns? Our tentative responses to all three questions are in the positive. -

Ethernet: an Engineering Paradigm

Ethernet: An Engineering Paradigm Mark Huang Eden Miller Peter Sun Charles Oji 6.933J/STS.420J Structure, Practice, and Innovation in EE/CS Fall 1998 1.0 Acknowledgements 1 2.0 A Model for Engineering 1 2.1 The Engineering Paradigm 3 2.1.1 Concept 5 2.1.2 Standard 6 2.1.3 Implementation 6 3.0 Phase I: Conceptualization and Early Implementation 7 3.1 Historical Framework: Definition of the Old Paradigm 7 3.1.1 Time-sharing 8 3.1.2 WANs: ARPAnet and ALOHAnet 8 3.2 Anomalies: Definition of the Crisis 10 3.2.1 From Mainframes to Minicomputers: A Parallel Paradigm Shift 10 3.2.2 From WAN to LAN 11 3.2.3 Xerox: From Xerography to Office Automation 11 3.2.4 Metcalfe and Boggs: Professional Crisis 12 3.3 Ethernet: The New Paradigm 13 3.3.1 Invention Background 14 3.3.2 Basic Technical Description 15 3.3.3 How Ethernet Addresses the Crisis 15 4.0 Phase II: Standardization 17 4.1 Crisis II: Building Vendor Support (1978-1983) 17 4.1.1 Forming the DIX Consortium 18 4.1.2 Within DEC 19 4.1.3 Within Intel 22 4.1.4 The Marketplace 23 4.2 Crisis III: Establishing Widespread Compatibility (1979-1984) 25 4.3 The Committee 26 5.0 Implementation and the Crisis of Domination 28 5.1 The Game of Growth 28 5.2 The Grindley Effect in Action 28 5.3 The Rise of 3Com, a Networking Giant 29 6.0 Conclusion 30 A.0 References A-1 i of ii ii of ii December 11, 1998 Ethernet: An Engineering Paradigm Mark Huang Eden Miller Charles Oji Peter Sun 6.933J/STS.420J Structure, Practice, and Innovation in EE/CS Fall 1998 1.0 Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the following individuals for contributing to this project. -

Paradigm Shift Damien Besancenot, Habib Dogguy

Paradigm Shift Damien Besancenot, Habib Dogguy To cite this version: Damien Besancenot, Habib Dogguy. Paradigm Shift. 2011. halshs-00590527v3 HAL Id: halshs-00590527 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00590527v3 Preprint submitted on 3 Jul 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Paradigm Shift Damien Besancenot, Universit´eParis 13 and CEPN Habib Dogguy, Universit´eParis 13 and CEPN June 10, 2011 Abstract This paper analyses the consequences of young researchers' scientific choice on the dynamics of sciences. We develop a simple two state mean field game model to analyze the competition between two paradigms based on Kuhn's theory of scientific revolutions. At the beginning of their ca- reer, young researchers choose the paradigm in which they want to work according to social and personal motivations. Despite the possibility of multiple equilibria the model exhibits at least one stable solution in which both paradigms always coexist. The occurrence of shocks on the param- eters may induce the shift from one dominant paradigm to the other. During this shift, researchers' choice is proved to have a great impact on the evolution of sciences. Keywords : Paradigm shift, Scientific choice, Research dynamics, Mean field game. -

Subjectivity and Critique : a Study of the Paradigm Shift in Critical Theory.”

“Subjectivity and Critique : A Study of the Paradigm Shift in Critical Theory.” by Alexander Reynolds A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Government Department of the London School of Economics, February 1995. UMI Number: U079B09 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U079B09 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F 720 2_ 2 Abstract of thesis. The German social-philosophical tradition of Critical Theory has recently undergone what its current practitioners have themselves described as a “paradigm shift”. Writers like Jurgen Habermas and Kari-Otto Apel are today attempting to reformulate the socially-critica! insights of Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno in new terms. Where Horkheimer and Adorno had tried to articulate their critique of existing social relations in a language of “subjectivity” and “objectivity” drawn largely from the classical German philosophical tradition, Habermas and Apel are trying to formulate an - ostensibly - similar critique in a language of “a priori intersubjectivity” drawn from the “ordinary language” and “speech-act" theory which has emerged since the Second World War in the Anglo-American philosophical sphere. -

TOWARD a SYSTEMIC THEORY of SYMBOLIC ACTION by PATRICK

TOWARD A SYSTEMIC THEORY OF SYMBOLIC ACTION By PATRICK MICHAEL McKERCHER B.A., San Diego State University, 1981 M.A., San Diego State University, 1984 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA March, 1993 Patrick Michael McKercher, 1993 ________ ___________________________ In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced Library shall make it degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the agree that permission for extensive freely available for reference and study. I further copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of AflJL The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE6 (2/88) ABSTRACT Though Kenneth Burke has often been dismissed as a brilliant but idiosyncratic thinker, this dissertation will argue that he is actually a precocious systems theorist. The systemic and systematic aspects of Burke’s work will be demonstrated by comparing it to the General Systems Theory (GST) of biologist Ludwig von Bertalanffy. Though beginning from very different starting points, Bertalanffy and Burke develop similar aims, methods, and come to remarkably similar conclusions about the nature and function of language. The systemic nature of Burke’s language philosophy will also become evident through an analysis of the Burkean corpus. -

Making a Paradigm Shift the Bamako 2008 Global Ministerial Forum on Research for Health | PAGE 12

Special Programme for Research & Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) sponsored by UNICEF/UNDP/World B a n k / W H O Special Programme for Research & Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) sponsored by UNICEF/UNDP/World B a n k / W H O No. 82 - M a r c h 2 0 0 9 Making a paradigm shift The Bamako 2008 Global Ministerial Forum on Research for Health | PAGE 12 Also in this issue 29 • Empowerment SAC • ANDI Task Force PAGE 30 • Chagas disease protocol 4 Research briefs 19 • ASTMH and rectal artesunate 7 TDR briefly 32 • DEEP on ineffective diagnostics Liberia diary: 24 HAT research in Uganda • Biosafety courses launched ‘greening’ in Mali M eet IN G S clinical trials in 33 • Sudan adopts HMM strategy 27 • Stewardship SAC a remote site • Environment, agriculture and 34 Publications infectious diseases 36 Grants Letter from the editor Powering sustainable research page n TDR we speak a great deal about Solar power generation capacity not only would as- 9 using the research that we do in sure the sustainability of the infrastructure invest- countries not only for a particular drug ment in Bolahun for other trials for neglected tropi- trial or project, but also to build more cal diseases, but it could potentially power existing “sustainable” research and health services facilities of a nearby health centre, and also Bolahun capacity in poorly resourced locales. High School. Now, a drug trial of moxidectin, a potential drug The high school, founded by monks in 1925 and a for the eradication of onchocerciasis in Africa, to be focus of Peace Corps volunteer activity in the 1960s conducted in Liberia and the Democratic Republic of and 1970s, has an interesting history. -

The Relationship Between the Aristotelian, Newtonian and Holistic Scientific Paradigms and Selected British Detective Fiction 1980 - 2010

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE ARISTOTELIAN, NEWTONIAN AND HOLISTIC SCIENTIFIC PARADIGMS AND SELECTED BRITISH DETECTIVE FICTION 1980 - 2010 HILARY ANNE GOLDSMITH A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Greenwich for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2010 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge the help and support I have received throughout my studies from the academic staff at the University of Greenwich, especially that of my supervisors. I would especially like to acknowledge the unerring support and encouragement I have received from Professor Susan Rowland, my first supervisor. iii ABSTRACT This thesis examines the changing relationship between key elements of the Aristotelian, Newtonian and holistic scientific paradigms and contemporary detective fiction. The work of scholars including N. Katherine Hayles, Martha A. Turner has applied Thomas S. Kuhn’s notion of scientific paradigms to literary works, especially those of the Victorian period. There seemed to be an absence, however, of research of a similar academic standard exploring the relationship between scientific worldviews and detective fiction. Extending their scholarship, this thesis seeks to open up debate in what was perceived to be an under-represented area of literary study. The thesis begins by identifying the main precepts of the three paradigms. It then offers a chronological overview of the developing relationship between these precepts and detective fiction from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Sign of Four (1890) to P.D.James’s The Black Tower (1975). The present state of this interaction is assessed through a detailed analysis of representative examples of the detective fiction of Reginald Hill, Barbara Nadel, and Quintin Jardine written between 1980 and 2010. -

Theoretical Approach to the Interaction Between the Meta-System Schemas of the Artificial (Built) Environment and Nature

Theoretical Approach to the Interaction Between the Meta-system Schemas of the Artificial (Built) Environment and Nature José L. Fernández-Solís, Ph. D. Kent D. Palmer, Ph. D. Timothy Ferris, Ph. D. Texas A&M University, 3137 TAMU, College Station, TX 77843-3137 USA P.O. Box 1632, CA 92867 USA University of South Australia, Mawson Lakes Blvd., Mawson Lakes, 5095 AU Emails: [email protected] ; [email protected] ; [email protected] Abstract: This is an exploration of how the artificial environment links with the natural environment and requires a conceptual construct that bridges these two environments. Palmer’s General Schema Theory, a highly theoretical work, elaborated on in a dissertation by Fernández-Solís (2006), provides a theory of schemas and a theory of the schema of meta-systems which will be useful for interpreting the relationship between the artificial and natural environment. The concept of meta-system is used first to generate and then to validate the concept of meta-industry. This paper argues that the building construction industry (which produces the built or artificial environment) that is categorized as an ‘industry’ by academia, actually acts as a meta-industry. Meta-industry is a concept that encapsulates an ‘industry of industries,’ which implies that the artificial and the natural environment interact at the meta-level. Climate change is construed as the reaction of the natural to the artificial environment at the meta- level. The approach to this pre-paradigmatic work uses the tools of philosophical and critical thinking, rationality and logic. General Schemas thinking at the meta- systemic level is presented as a new approach towards the formation of a novel paradigm of the artificial environment. -

The Seduction of Feminist Theory

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2011 The Seduction of Feminist Theory Erin Amann Holliday-Karre Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Holliday-Karre, Erin Amann, "The Seduction of Feminist Theory" (2011). Dissertations. 168. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/168 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2011 Erin Amann Holliday-Karre LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE SEDUCTION OF FEMINIST THEORY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN ENGLISH LITERATURE BY ERIN HOLLIDAY-KARRE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 2011 Copyright by Erin Holliday-Karre, 2011 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am eternally indebted to Pamela L. Caughie not only for her tireless work on and enthusiastic support of this project but also for her friendship, which ultimately pushed me to persist with an “ambitious” dissertation. To Anne Callahan for spending so many hours in her writing studio helping me search for just the right word to capture what I was trying to say. To Holly Laird for graciously acknowledging in my work a previous aspiration of her own and for her masterful editorial skills.