The Future Housing Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

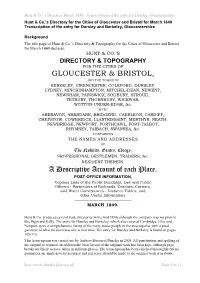

GLOUCESTER & BRISTOL, a Descriptive Account of Each Place

Hunt & Co.’s Directory March 1849 - Transcription of the entry for Dursley, Gloucestershire Hunt & Co.’s Directory for the Cities of Gloucester and Bristol for March 1849 Transcription of the entry for Dursley and Berkeley, Gloucestershire Background The title page of Hunt & Co.’s Directory & Topography for the Cities of Gloucester and Bristol for March 1849 declares: HUNT & CO.'S DIRECTORY & TOPOGRAPHY FOR THE CITIES OF GLOUCESTER & BRISTOL, AND THE TOWNS OF BERKELEY, CIRENCESTER, COLEFORD, DURSLEY, LYDNEY, MINCHINHAMPTON, MITCHEL-DEAN, NEWENT, NEWNHAM, PAINSWICK, SODBURY, STROUD, TETBURY, THORNBURY, WICKWAR, WOTTON-UNDER-EDGE, &c. W1TH ABERAVON, ABERDARE, BRIDGEND, CAERLEON, CARDIFF, CHEPSTOW, COWBRIDCE, LLANTRISSAINT, MERTHYR, NEATH, NEWBRIDGE, NEWPORT, PORTHCAWL, PORT-TALBOT, RHYMNEY, TAIBACH, SWANSEA, &c. CONTAINING THE NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF The Nobility, Gentry, Clergy, PROFESSIONAL GENTLEMEN, TRADERS, &c. RESlDENT THEREIN. A Descriptive Account of each Place, POST-OFFICE INFORMATION, Copious Lists of the Public Buildings, Law and Public Officers - Particulars of Railroads, Coaches, Carriers, and Water Conveyances - Distance Tables, and other Useful Information. __________________________________________ MARCH 1849. ___________________________________________ Hunt & Co. produced several trade directories in the mid 1850s although the company was not prolific like Pigot and Kelly. The entry for Dursley and Berkeley, which also covered Cambridge, Uley and Newport, gave a comprehensive listing of the many trades people in the area together with a good gazetteer of what the town was like at that time. The entry for Dursley and Berkeley is found on pages 105-116. This transcription was carried out by Andrew Barton of Dursley in 2005. All punctuation and spelling of the original is retained. In addition the basic layout of the original work has been kept, although page breaks are likely to have fallen in different places. -

City of Gloucester

CITY OF GLOUCESTER PLANNING COMMITTEE ON 6TH OCTOBER 2009 DELEGATED DECISIONS 1ST – 31 ST AUGUST 2009 Development Services Group Manager, Herbert Warehouse, The Docks, Gloucester PT06109C INDEX Ward Page Abbey ............................................................................................... 1 Barnwood ......................................................................................... 1 Barton and Tredworth ....................................................................... 2 Elmbridge ......................................................................................... 2 Grange.............................................................................................. 2 Hucclecote ....................................................................................... 3 Kingsholm and Wotton...................................................................... 4 Longlevens ....................................................................................... 4 Matson and Robinswood .................................................................. 5 Moreland........................................................................................... 5 Podsmead ........................................................................................ - Quedgeley Fieldcourt........................................................................ 6 Quedgeley Severnvale...................................................................... 7 Tuffley ............................................................................................. -

Severn Estuary Climate Change Citations Database 1. CLIMATE

Severn Estuary Climate Change Citations Database Version 5 October 2010 Compiled by Cardiff University and Severn Estuary Partnership also available as ENDNOTE Database Software File CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM Severn Estuary Climate Change Citations Database ................................................................ 1 1. CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS ................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Amenities................................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Critical Infrastructure............................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Cultural & Archaeological Heritage..................................................................................... 6 1.4 Geology.................................................................................................................................13 1.5 Habitats & Ecosystems.......................................................................................................14 1.6 Nutrients and Contaminants ..............................................................................................28 1.7 Regional and Local Climate Change................................................................................36 1.8 Sea Level..............................................................................................................................38 1.9 Storm Surges and Coastal Flooding ................................................................................44 -

Walk Westward Now Along This High Ridge and from This Vantage Point, You Can Often Gaze Down Upon Kestrels Who in Turn Are Scouring the Grass for Prey

This e-book has been laid out so that each walk starts on a left hand-page, to make print- ing the individual walks easier. When viewing on-screen, clicking on a walk below will take you to that walk in the book (pity it can’t take you straight to the start point of the walk itself!) As always, I’d be pleased to hear of any errors in the text or changes to the walks themselves. Happy walking! Walk Page Walks of up to 6 miles 1 East Bristol – Pucklechurch 3 2 North Bristol – The Tortworth Chestnut 5 3 North Bristol – Wetmoor Wood 7 4 West Bristol – Prior’s Wood 9 5 West Bristol – Abbots Leigh 11 6 The Mendips – Charterhouse 13 7 East Bristol – Willsbridge & The Dramway 16 8 Vale of Berkeley – Ham & Stone 19 Walks of 6–8 miles 9 South Bristol – Pensford & Stanton Drew 22 10 Vale of Gloucester – Deerhurst & The Severn Way 25 11 Glamorgan – Castell Coch 28 12 Clevedon – Tickenham Moor 31 13 The Mendips – Ebbor Gorge 33 14 Herefordshire – The Cat’s Back 36 15 The Wye Valley – St. Briavels 38 Walks of 8–10 miles 16 North Somerset – Kewstoke & Woodspring Priory 41 17 Chippenham – Maud Heath’s Causeway 44 18 The Cotswolds – Ozleworth Bottom 47 19 East Mendips – East Somerset Railway 50 20 Forest of Dean – The Essence of the Forest 54 21 The Cotswolds – Chedworth 57 22 The Cotswolds – Westonbirt & The Arboretum 60 23 Bath – The Kennet & Avon Canal 63 24 The Cotswolds – The Thames & Severn Canal 66 25 East Mendips – Mells & Nunney 69 26 Limpley Stoke Valley – Bath to Bradford-on-Avon 73 Middle Hope (walk 16) Walks of over 10 miles 27 Avebury – -

SHARPNESS VALE: Natural Neighbourhoods 1

S HARPNESS V ALE: natural neighbourhoods P16-0821_18C | November 2019 THE TEAM We are creating a network of natural neighbourhoods that are exemplar of sustainable living and innovation, with infrastructure in place from the outset. SHARPNESS LYDNEY DOCKS SHARPNESS VALE (PROPOSED) A38 BERKELEY M5 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. VISION 4 3. WHY AT SHARPNESS? 7 4. THE POTENTIAL SCALE OF DEVELOPMENT 10 5. REDUCING OUR CARBON FOOTPRINT 16 6. DELIVERING A WEB OF GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE 18 7. INNOVATION, EMPLOYMENT AND LEARNING 38 8. MOVEMENT STRATEGY 40 9. HOME AND WELL-BEING 49 CAM Pegasus 10. BUILDING WITH NATURE 51 Design 11. DELIVERABILITY & NEXT STEPS 53 Pegasus Design Pegasus House Querns Business Centre Whitworth Road Cirencester GL7 1RT www.pegasusgroup.co.uk I T 01285 641717 Prepared by Pegasus Design Pegasus Design is part of Pegasus Group Ltd November 2019 Project code P16-0821 COPYRIGHT The contents of this document must not be copied or reproduced in whole or in part without the written consent of Pegasus Planning Group Ltd. Crown copyright. All rights reserved, Licence number 100042093. THE INTEGRATION OF ROUTES THAT SUPPORT CLEAR NETWORK OF PERMEABLE DRIVEWAYS TO TREES AND HEDGEROWS ALLOTMENTS TO PROVIDE CHILDREN WALKING OR FOOTPATHS AND CYCLEPATHS HELP DRAINAGE INTEGRATED WITHIN LOCAL FOOD, OCCUPATIONAL CYCLING TO SCHOOL SAFELY MAKING THE DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT FOR WILDLIFE, THERAPY AND AS A MECHANISM AND EASILY WELCOMING FOR PEDESTRIANS SHADE AND IMPROVED AIR OF SOCIAL INCLUSION AND CYCLISTS QUALITY 2 SHARPNESS VALE: natural neighbourhoods 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 This document has been produced in support of Stroud GreenSquare Group District Council’s Local Plan Review, which highlights 1.5 GreenSquare was formed is 2008 – but can trace its the option of planning a new sustainable settlement at origins back more than 150 years. -

Kings Copse Kingsway Village, Quedgeley, Gloucester

Kings Copse Kingsway Village, Quedgeley, Gloucester Discover a range of beautiful 2, 3, 4 & 5 bedroom homes Welcome to our carefully selected collection of homes. Built with the same passion and Computer generated image commitment that we have had for over is indicative of The Stanton at Kings Copse 100 years, we are proud of the homes we build and we hope you’ll love them. Welcome to Kings Copse Discover a range of beautiful 2, 3, 4 & 5 bedroom homes situated in the sought-after Kingsway Village. Artist’s impression of a street scene at Kings Copse The Gosford at Kings Copse The Gosford at Kings Copse “The moment you enter a Taylor Wimpey home you’ll see that we design and build our homes and communities around you.” The Gosford at Kings Copse Lifestyle Welcome to a home where all the fixtures From the day you move in, you’ll love the fact that everything in your new home We use traditional construction techniques incorporating modern materials The moment you enter a Taylor Wimpey home you’ll see that we design and is clean and untouched. Your new home will be decorated in neutral colours, in our homes. Environmentally friendly features like efficient heating systems, build our homes and communities around you. But we build more than just new and fittings are brand new and unused. so you’ll get a blank canvas to stamp your own style and personality on double glazed windows, high levels of wall and loft insulation and well-designed homes – last year we helped to create and maintain over 15,000 jobs in the Where you won’t need to worry about DIY from day one. -

Sydney Arthur Monckton Copeman (1862-1947) (From a Portrait by Frank Eastman, R.A., in the Possession of Dr

Sydney Arthur Monckton Copeman (1862-1947) (From a portrait by Frank Eastman, R.A., in the possession of Dr. W. S. C. Copeman.) Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.226, on 25 Sep 2021 at 05:16:21, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025727300012722 THE PREVENTION OF SMALLPOX: FROM EDWARD JENNER TO MONCKTON COPEMAN* by SIR ARTHUR SALUSBURY MAcNALTY, K.C.B. MY first and pleasant duty is to express my thanks to the Faculty of the History of Medicine and Pharmacy of the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries for appointing me to give the Inaugural Monckton Copeman Lecture. In selecting the 'Prevention of Smallpox from Edward Jenner to Monckton Copeman' as the subject of the Lecture, I value the privilege of paying a tribute to two great benefactors of mankind. It is appropriate at the outset to give you some account of the man in whose memory this Lecture has been founded. OUTLINE OF THE LIFE OF DR. S. MONCKTON COPEMAN Sydney Arthur Monckton Copeman was born at Norwich on 21 February, 1862. His father was the Rev. Canon Arthur Charles Copeman, LL.D., Canon and Rural Dean of Norwich. Before taking Holy Orders, Canon Copeman qualified with the M.B. London in 1848, being gold medallist in anatomy and physiology. Preceding generations of the family were private bankers in Norwich; but medicine was further represented by the Canon's elder brother, Edward Copeman, M.D., F.R.C.P. -

Hello Comments Have Been Submitted Regarding Proposal Development

Hello Comments have been submitted regarding proposal Development of an automated petrol filling station. at Asda Supermarket Kingsway Business Park Newhaven Road Quedgeley Gloucester GL2 2SN. The following objection was made today by Mr Chuen Tsang. live in Kingsway and I shop daily at Asda, Kingsway. I object to the proposed plans for a petrol filling station for the following reasons:- 1. It appears that the petrol station is located on the edge of the site (near the roundabout). The concern is that this is located too close to the residential properties across the site and also too close to the children's recreational area across from Asda. The concern is that the fumes will spread to these areas causing pollution and potential health issues to the residents. 2. We already have petrol stations that are 3 minutes away in Tesco, Quedgeley, Shell on Bristol Road and a petrol station on the Hardwicke roundabout. There is more than enough petrol facilities within easy reach. 3. On an aesthetic level, it is not appealing to see and potentially smell a petrol station as you enter Kingsway Village as you walk and drive. It will spoil the beauty of the surrounding area. The entrance of Kingsway should be kept as it is with the beautiful and pleasant green landscaping which will help to balance the busy-ness of the main access road that connects to the dual carriageway. 4. Over the past 3 years of living here, the amount of traffic on this access road has grown substantially and this will only increase further and could be quite dangerous if the traffic queues up (especially in bad weather and poor visibility days). -

Wisloe Development the Ernest Cook Trust

LEGEND: Site boundary Existing green infrastructure Existing Public Right of Way Proposed structure planting Proposed tree planting 6 Proposed integrated and biodiverse SUDs 4 6 Proposed wildflower/species rich grass margins 5 Central landscape feature Key views from AONB Local views from A38 1 Potential links to PROW 1 network Potential access 2 4 3 Landscape Strategy 6 1. Key green infrastructure as a sinuous core 2. Manage and enhance boundary vegetation 3. Central landscape feature 4. Public Open Space 5 5. Integrated SUDs 4 6. Connect to wider Public Right of Way network 2 6 2 DRAFT WISLOE DEVELOPMENT LANDSCAPE VISUAL ANALYSIS & STRATEGY PLAN THE ERNEST COOK TRUST Reproduced from 0:000000 map by permission of the Ordnance Survey ® Mark Revision on behalf of The Controller of Date 08.10.2019 Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Drawing No. REV © Crown Copyright 2000. 44396 -04 Scale NTS All rights reserved. Licence No. 100017583. Drawn KH Checked NJ © Peter Brett Associates LLP 5km LEGEND: 6 Site boundary 7 Watercourse 1 View Location National Landscape Character¹ 8 NCA 106 Severn and Avon Vales NCA 107 Cotswolds The study area is within the county of Gloucestershire NCA 106 Severn and Avon Vales Gloucestershire Landscape Character Types² 6 Unwooded vale Drained Riverine Farmland and Grazed Salt 7 Marsh 8 Littoral Sands and Rock Outcrops 7 18 Settled Unwooded Vale SV6A 23 High Wold Dip Slope 26 Escarpment 18 27 Secluded Valleys 4 3 28 Escarpment Valleys Low Sandstone Hills 2 29 31 Gently Undulating Lowland Farmland Gloucestershire Character Areas³ 299 1 Character areas within Settled Unwooded Vale SV6A: Vale of Berkeley Cotswolds Landscape Character Areas⁴ 1A: Cam Long Down, Peaked Down and Downham Hills 31 Notes: 1. -

Wedding Brochure 1056369463.Pdf

Dear Sir/Madam Thank you for your recent enquiry regarding Wedding facilities at The Barn at Berkeley. Please find attached details regarding the services we can provide. You can also find out more about us by checking out our website at www.thebarnatberkeley.co.uk. The Barn provides the perfect venue for your Special Day. Our standard Wedding Breakfast prices include a three-course Wedding Banquet with tea/coffee to finish, table linen, cutlery, china, wedding co-ordinator, toast master and full staffing. However, please note that packages can be tailored to suit you and your requirements. The Venue is licensed for Civil Ceremonies which can be held in our purpose-built suite, The Loft, which can accommodate up to 150 guests for the ceremony. It’s a must to come and view with its balcony and chandelier lighting. We also have a Pergola in our Wedding Garden which is licensed for outdoor ceremonies. The large garden with Cotswold stonewalling, oriental pond and pergola is completely private and for your sole use and is great for those wedding photos. We can also cater for your evening reception and can provide an array of evening food. Please find sample evening menus enclosed. I hope the above information is of interest to you and that we have provided a taste of what our superb venue has to offer. If you would like to view any of the facilities at The Barn at Berkeley or if you have any further queries, please feel free to contact me on the email address or phone number below. -

Imjinthe Voice of the Innsworth Station Community

the The Voice of the Innsworth imjinStation Community April 2016 Covering HQ ARRC, HQ 1 (UK) Sigs Bde, DBS, Ashchurch, ARRC Sp Bn, 252 Sig Sqn COMARRC’s Introduction The excitement of Christmas is now seems distant memory and Spring is now upon us. For those who have joined the ARRC family since the last publication, a very warm welcome to you and your families. Spring in Gloucestershire is a wonderful time and I hope you will take the opportunity to explore the local and regional attractions that are on offer in the lead in to Summer. The editorial team have included a good selection of attractions on the events page further inside. This year will be professionally challenging but deeply rewarding as we prepare to take over as NATO’s high readiness reaction force Headquarters on 1st January 2017. This will involve us taking part in a number of challenging training exercises, both in the UK and overseas. It will be a busy time for all of us and the support our families provide will be an essential part of how we generate success over the coming months. Sadly, this is the last time I write my introduction to the Imjin magazine. I leave the ARRC this Summer after a number of very happy years with the ARRC Group both in Germany and here in Gloucestershire. Your service and friendship to Helen and me has been tremendous; thank you. We leave with some tremendous memories and it has been a real privilege to command the Allied Rapid Reaction Coprs. -

I Am a Resident of Berkeley And, Whilst

From: Sent: 21 January 2020 11:43 To: _WEB_Local Plan Subject: Sharpness Garden Village Development Plan Follow Up Flag: Follow up Flag Status: Flagged To whom it may concern: I am a resident of Berkeley and, whilst understanding the Council’s dilemma, feel that what is proposed for green belt, agricultural land between Berkeley and Sharpness is inappropriate. I realise that this is only one site of several around the area, and I appreciate that much of the land within the Stroud district is not suitable for development – being either very hilly or within the AONB However, just because the land between Berkeley and Sharpness is relatively flat, does not make it suitable or desirable for a development of this nature. I walked up on Stinchcombe Hill at the weekend and looked west over towards Sharpness, the Severn and the hills beyond. To imagine this beautiful rural area covered by houses, a whole new town, is unthinkable. Gloucestershire, and the Severn Vale and Vale of Berkeley, provide us with some of the most outstanding landscapes in the country. It is an historic area where growth has been gentle, peppered by small towns and villages with the only conurbations, to date, around Gloucester, Cheltenham, Stroud and Bristol to the south. To deposit a new town (hardly a Garden Village) on this green and pleasant landscape would be destruction on a monumental scale. My initial response is to question the Government’s model for growth over the next 25-30 years. They have been wrong before – think of closure of school places because the pupil population was decreasing – now schools are over-subscribed and bursting at the seams.