Defining the West of England's Genius Loci: 'Land of Limestone and Levels'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5.6 Flood Risk Assessment Appendix N CAFRA Rlw Results 2019 Tidal.Xlsx”)

Portishead Branch Line (MetroWest Phase 1) TR040011 Applicant: North Somerset District Council 5.6, Flood Risk Assessment, Part 1 of 17 The Infrastructure Planning (Applications: Prescribed Forms and Procedure) Regulations 2009, regulation 5(2)(e) Planning Act 2008 Author: CH2M Date: November 2019 1-1 The original submission version of this document can be found in Appendix 17.1 of the ES. The document contained within the ES will not be updated. However, this standalone version of this document may be updated and the latest version will be the final document for the purposes of the Order. 1-2 Notice © Copyright 2019 CH2M HILL United Kingdom. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of CH2M HILL United Kingdom, a wholly owned subsidiary of Jacobs. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Limitation: This document has been prepared on behalf of, and for the exclusive use of Jacobs’ client, and is subject to, and issued in accordance with, the provisions of the contract between Jacobs and the client. Jacobs accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for, or in respect of, any use of, or reliance upon, this document by any third party. Where any data supplied by the client or from other sources have been used, it has been assumed that the information is correct. No responsibility can be accepted by Jacobs for inaccuracies in the data supplied by any other party. The conclusions and recommendations in this report are based on the assumption that all relevant information has been supplied by those bodies from whom it was requested. -

The Manor House

The Manor House Monkton Combe, Bath The Manor House Monkton Combe, Bath, BA2 7HD A magnificent medieval country manor house, approximately 2.5 miles from Bath Spa station. Accommodation Entrance Hall • Reception hall • Drawing room • Dining room Games room • Kitchen/breakfast room • Utility room • Conservatory Ground floor en suite bedroom 5 first floor en suite bedrooms • 3 second floor en suite bedrooms Drive way parking • Gardens Luke Brady Savills Bath Edgar House, 17 George Street Bath, BA1 2EN [email protected] 01225 474501 Description The Manor House is a superb detached ancient country house situated in a secluded position in the village of Monkton Combe, approximately 2.5 miles from Bath Spa station in the UNESCO World Heritage Site – the City of Bath. This restful rambling medieval Manor House is in a rural valley in a recognised ‘Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty’. Documented in the Hale Manuscript of 1262, the property has a wealth of beautiful architectural features, including an ancient fireplace, exposed beams and exquisite ceiling detail in the drawing room. The property has four reception rooms on the ground floor, two of which have log fires including a Tudor inglenook fireplace dating back to the mid-16th century. Of particular note is the formal drawing room ( once a billiard room ) that overlooks the pretty gardens. There is an open fire, wooden floors and exquisite ceiling detail. The kitchen/breakfast room leads into both the Victorian glass house conservatory and the utility room with doors to the gardens. There are eight en suite bedrooms, individually styled – one on the ground floor and four on the first floor. -

Bath & North East Somerset Council

Bath & North East Somerset Council MEETING: Development Control Committee AGENDA 3rd September 2014 ITEM MEETING NUMBER DATE: RESPONSIBLE Lisa Bartlett, Development Manager of Planning and OFFICER: Transport Development (Telephone: 01225 477281) TITLE: LIST OF APPLICATIONS DETERMINED UNDER DELEGATE AUTHORITY FOR THE PERIOD - 18 th July 2014 to 12 th August 2014 DELEGATED DECISIONS IN RESPECT OF PLANNING ENFORCEMENT CASES ISSUED FOR PERIOD WARD: ALL BACKGROUND PAPERS: None AN OPEN PUBLIC ITEM INDEX Applications determined by the Development Manager of Planning and Transport Development Applications referred to the Chair Delegated decisions in respect of Planning Enforcement Cases APPLICATIONS DETERMINED BY THE DEVELOPMENT MANAGER OF PLANNING AND TRANSPORT DEVELOPMENT App. Ref . 14/01073/LBA Type: Listed Building Consent (Alts/exts) Location: 9 Duke Street City Centre Bath Bath And North East Somerset BA2 4AG Ward: Abbey Parish: N/A Proposal: Internal works to facilitate partition wall (regularisation). Applicant: Mr Michael Fortune Decision Date: 25 July 2014 Expiry Date: 22 July 2014 Decision: REFUSE Details of the decision can be found on the Planning Services pages of the Council’s website by clicking on the link below: http://idox.bathnes.gov.uk/WAM/showCaseFile.do?appNumber=14/01073/LBA App. Ref . 14/01316/LBA Type: Listed Building Consent (Alts/exts) Location: New Church 10 Henry Street City Centre Bath Bath And North East Somerset Ward: Abbey Parish: N/A Proposal: External alterations for the provision of 2 flues Applicant: Deloitte LLP Decision Date: 4 August 2014 Expiry Date: 11 August 2014 Decision: CONSENT Details of the decision can be found on the Planning Services pages of the Council’s website by clicking on the link below: http://idox.bathnes.gov.uk/WAM/showCaseFile.do?appNumber=14/01316/LBA App. -

GO AVON 2021 Update: Bus Transportation Available!!

Michael Renkawitz, Principal Dr. Diana DeVivo, Assistant Principal David Kimball, Assistant Principal Todd Dyer, Director of School Counseling Timothy P. Filon, Coordinator of Athletics GO AVON! UPDATE August 19, 2021 Dear Class of 2025 and students new to Avon: On August 11 you received an invitation from me to participate in GO AVON!, an orientation program prior to the start of school. We are fortunate that we have a dedicated group of AHS upperclassmen who have planned this orientation session for you. I am thrilled to inform you that bus transportation is now available! Specialty Transportation will begin their morning pick-up at 8:15 a.m. using the revised bus routes listed below. Please note that these revised bus routes will be used on GO AVON! Day only and your child may be picked up/dropped off at a stop different from their regularly assigned bus location used during the school year. Students should take the bus at the nearest bus location listed below. Buses will be shared with Avon MIddle School on this day. AHS students are asked to sit in the back two sections of the bus for cohorting purposes. At dismissal, students will board the same lettered bus as they came on. Please have your child write down the letter of his/her bus, as it will be the same bus that brings your child home. Students will be dropped off along bus routes within 30 minutes of dismissal depending on the route. If you prefer to drive your child, students may be dropped off at AHS no earlier than 8:45 a.m. -

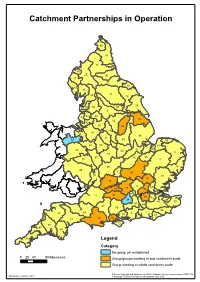

Catchment Partnerships in Operation

Catchment Partnerships in Operation 100 80 53 81 89 25 90 17 74 26 67 33 71 39 16 99 28 99 56 95 2 3 20 30 37 18 42 42 85 29 79 79 15 43 91 96 21 83 38 50 61 69 51 51 59 92 62 6 73 97 45 55 75 7 88 24 98 8 82 60 10 84 12 9 57 87 77 35 66 66 78 40 5 32 78 49 35 14 34 49 41 70 94 44 27 76 58 63 1 48 23 4 13 22 19 46 72 31 47 64 93 Legend Category No group yet established 0 20 40 80 Kilometres GSurobu cpa/gtcrhomupesn wt orking at sub catchment scale WGrhooulpe wcaotrckhinmge antt whole catchment scale © Crown Copyright and database right 2013. Ordnance Survey licence number 100024198. Map produced October 2013 © Copyright Environment Agency and database right 2013. Key to Management Catchment ID Catchment Sub/whole Joint ID Management Catchment partnership catchment Sub catchment name RBD Category Host Organisation (s) 1 Adur & Ouse Yes Whole South East England Yes Ouse and Adur Rivers Trust, Environment Agency 2 Aire and Calder Yes Whole Humber England No The Aire Rivers Trust 3 Alt/Crossens Yes Whole North West England No Healthy Waterways Trust 4 Arun & Western Streams Yes Whole South East England No Arun and Rother Rivers Trust 5 Bristol Avon & North Somerset Streams Yes Whole Severn England Yes Avon Wildlife Trust, Avon Frome Partnership 6 Broadland Rivers Yes Whole Anglian England No Norfolk Rivers Trust 7 Cam and Ely Ouse (including South Level) Yes Whole Anglian England Yes The Rivers Trust, Anglian Water Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Wildlife 8 Cherwell Yes Whole Thames England No Trust 9 Colne Yes Whole Thames England -

Recreation 2020-21

Conservation access and recreation 2020-21 wessexwater.co.uk Contents About Wessex Water 1 Our commitment 2 Our duties 2 Our land 3 Delivering our duties 3 Conservation land management 4 A catchment-based approach 10 Engineering and sustainable delivery 12 Eel improvements 13 Invasive non-native species 14 Access and recreation 15 Fishing 17 Partners Programme 18 Water Force 21 Photo: Henley Spiers Henley Photo: Beaver dam – see 'Nature’s engineers' page 7 About Wessex Water Wessex Water is one of 10 regional water and sewerage companies in England and About 80% of the water we supply comes from groundwater sources in Wiltshire Wales. We provide sewerage services to an area of the south west of England that and Dorset. The remaining 20% comes from surface water reservoirs which are includes Dorset, Somerset, Bristol, most of Wiltshire, and parts of Gloucestershire, filled by rainfall and runoff from the catchment. We work in partnership with Hampshire and Devon. Within our region, Bristol Water, Bournemouth Water and organisations and individuals across our region to protect and restore the water Cholderton and District Water Company also supply customers with water. environment as a part of the catchment based approach (CaBA). We work with all the catchment partnerships in the region and host two catchment partnerships, Bristol What area does Wessex Water cover? Avon and Poole Harbour, and co-host the Stour catchment initiative with the Dorset Wildlife Trust. our region our catchments Stroud 8 Cotswold South Gloucestershire Bristol Wessex -

The Bristol Brass Industry: Furnace Structures and Their Associated Remains Joan M Day

The Bristol brass industry: Furnace structures and their associated remains Joan M Day Remains of the once-extensive Bristol brass industry failed appear to have been complex. Political and can still be seen at several sites on the banks of the economic developments of the time contributed to A von and its tri butaries between Bath and Bristol.! varying extents. So too, did the availability of raw They are relics of the production of brass and its materials and good sources of fuel and waterpower, but manufacture which nourished during the eighteenth technical innovation in the smelting of copper, which century to become the most important industry of its was being evolved locally, provided a major component kind in Europe, superseding continental centres of of the initial success.3 It laid foundations for Bristol's similar production. By the close of the century Bristol domination of the industry throughout the greater part itself was challenged by strong competition and the of the eighteenth century. adoption of new techniques in Birmingham, and thereafter suffered a slow decline. Still using its Significantly, it was Abraham Oarby who was eighteenth-century water-powered methods the Bristol responsible as 'active man', together with Quaker industry just managed to survive into the twentieth partners, for launching the Bristol company in 1702. century, finally closing in the 1920s.2 After some five years' experience in employing coal• fired techniques in the non-ferrous metals industry he The factors which gave impetus to the growth -

Princes Court Bro 2-19

PRINCES COURT YATTON | BRISTOL | SOMERSET VILLAGE LIFE CLOSE TO TOWN, CITY & COAST 17 HIGH STREET, YATTON, BRISTOL BS49 4JD PRINCES COURT YATTON | BRISTOL | SOMERSET VILLAGE LIFE... Yatton is a charming village, surrounded by glorious countryside and close to the stunning North Somerset coastline yet it’s location just 11 miles south west of Bristol makes it hugely convenient for commuters, particularly with its mainline rail links to the city. Nestling in the foothills of historic Cadbury Hill, Yatton is situated equidistantly between Clevedon to the north, View across Yatton from Cadbury Hill Weston-super-Mare to the west and the Mendip Hills, an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, to the East. This thriving yet traditional village offers a convenient Renowned for The Strawberry Line (taking its name from the range of local facilities including a bank, supermarket, cargo this former railway line carried from the strawberry post office, library, doctor’s surgery, chemist, optician, fields of Cheddar) this glorious heritage trail provides a 10 dentist, hairdressers, hardware shop and a range of local mile traffic free route that takes you through varied independent stores located along its High Street. With landscapes of wildlife-rich wetlands, cider apple orchards, café’s and coffee shops, bakeries and a number of popular wooded valleys and picturesque villages between Yatton and pubs within the village it provides everything you need Cheddar, with further extensions planned to connect from right on the doorstep. Clevedon to Wells. The exclusive Double Tree by Hilton Cadbury House Numerous golf courses are located nearby at Congresbury, Hotel is located closeby where you can enjoy a meal at Clevedon, Tickenham Worlebury and Weston-super-Mare. -

HIGHLIGHTS the THREE COUNTIES KF Highlights Layout 1 05/02/2016 16:05 Page 5

HIGHLIGHTS THE THREE COUNTIES KF Highlights_Layout 1 05/02/2016 16:05 Page 5 THE BUYING SOLUTION Jonathan and Claire have purchased over £605,000,000 of property in Worcestershire, Herefordshire and the Cotswolds Whether you’re seeking the valley that catches the morning sunlight, that perfectly situated central regency townhouse, the finest picks of the social calendar or even the best shortcuts for the school run, Jonathan and Claire know the region inside out. The Buying Solution team provides property search and acquisition in London and throughout the UK. Jonathan Bramwell & Claire Owen, TBS Cotswolds specialists +44 (0)1608 503935 TheBuyingSolution.co.uk @TBSBuyingAgents KF Highlights_Layout 1 05/02/2016 16:05 Page 5 THE BUYING SOLUTION Welcome to Knight Frank’s Three Counties Highlights. In this year’s edition, we look at the prevailing conditions and trends that have shaped the property market in the region and also feature a selection of properties marketed by our teams during 2015. WELCOME Of course the big UK story of the year was the surprise election result in May. In property terms the uncertainty surrounding the outcome – and the possible Jonathan and Claire have introduction of the so-called Mansion Tax – had the effect of putting the brakes on a market already slowed by the increase in stamp duty introduced at the end purchased over £605,000,000 of 2014. However, by the late summer of 2015 the market was showing signs of property in Worcestershire, of absorbing these factors and getting back to business as usual. Herefordshire and the Cotswolds If there has been any lasting impact it is that sensible pricing levels have been the key to achieving successful sales. -

Mining the Mendips

Walk Mining the Mendips Discover the hidden history of a small Mendips village Black Down in winer © Andrew Gustar, Flickr (CCL) Time: 3 hours Distance: 6 miles Landscape: rural Welcome to the Mendips in Somerset. This is Location: an area of limestone escarpments and open Shipham, Somerset countryside; with rich and varied scenery, magnificent views and a fascinating history. Start: The Square, Shipham BS25 1TN Discover why the area’s curious geology made Finish: this a centre of lead and zinc mining and find Lenny’s Cafe out how the lives of villagers changed during the ‘boom and bust’ stages of Mendip’s mining Grid reference: past. ST 44416 57477 Rich resources need defending and this walk Keep an eye out for: will take you on a journey through the past Wonderful views of the Bristol Channel and its islands from an Iron Age hill fort to the remains of a fake decoy town designed to distract German bombers away from Bristol. Thank you! This walk was created by Andrew Newton, a Fellow of The Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) Every landscape has a story to tell – find out more at www.discoveringbritain.org Route and stopping points 01 Shipham Square 02 Layby on Rowberrow Lane 03 The Swan Inn, Rowberrow Lane 04 Rowberrow Church 05 Dolebury Warren Iron Age Hill Fort 06 Junction between bridleway to Burrington Combe and path to Black Down 07 Black Down 08 Starfish Control Bunker 09 Rowberrow Warren Conifer plantation 10 The Slagger’s Path 11 Gruffy Ground 12 St Leonard’s Church 13 Lenny’s Café Every landscape has a story to tell – Find out more at www.discoveringbritain.org 01 Shipham Square Welcome to the Mendips village of Shipham. -

Secretary's Report. 1937-1944

100 SECRETARY'S REPORT SECRETARY'S REPORT 101 1943. EAST TWIN SWALLET surveyed. 1944. In March of this year a new cave system was entered after a Secretary's Report, 1937-1944. successful dig had been carried out in a dry swallet close to the Society's bath. The activities of the Society, like those of so many others, have The new cave is of rather a different character from necessarily had to be curtailed somewhat during the past few years others in the Burrington area, and contains several large owing to wartime restrictions. vertical avens, one of which is over 60 ft. in height, and We have suffered from the loss of active members and have had makes one of the best rope ladder climbs in Mendip. In it largely to neglect some branches of our work, by reason of lack of also are some very fine formations, including two remarkable time, manpower, and transport facilities, but aHer a period of readjust white curtains, about 6 ft. long, in which run bands of colour. ment the Society has settled down to the new conditions, and is still The cave has been penetrated to a depth of about 200 ft. very active. and work is in progress on the mud ' choke at the bottom. During the years 1940-43 we were glad to see a number of our A full account of the cav~ will appear in the he;xt issue friends from King's College, London, taking an interest in the Society, of Proceedings when the task of surveying and photographing and in 1941 and 1942 two of their members served on the Committee. -

ANNEX to Proof of Evidence- C Tudor

Expansion of Bristol Airport to 12mppa – Planning Appeal PINS Ref. APP/DO121/W/20/3259234 Planning Application Ref.: 18/P/5118/OUT ANNEX to LANDSCAPE (Mendip Hills AONB and setting) PROOF of EVIDENCE for XR Elders Christine Tudor BA Hons, Dip LP, M Phil LA, CMLI, FRGS XR/W5/2 June 2021 CONTENTS Five Letters from the Mendip Hills AONB Partnership to N. Somerset Council 1. West of England Joint Spatial Plan – Consultation 8/1/2018, 2. Airport Outline Planning Application – Scoping 23/7/18, 3. Joint Spatial Plan (JSP) – Additional Evidence Consultation 7/1/19, 4. Airport Outline Planning Application 29/1/19, 5. Airport Outline Planning Application 13/5/19) Mendip Hills AONB Partnership Charterhouse Centre, Blagdon Bristol BS40 7XR t: 01761 462338 e:[email protected] w: www.mendiphillsaonb.org.uk West of England Joint Spatial Plan c/o South Gloucestershire Council Planning P O Box 1954 Bristol BS37 0DD 8 January 2018 Dear Sir/Madam, West of England Joint Spatial Plan – Consultation With reference to the West of England Joint Spatial Plan (JSP) consultation, herewith comments from the Mendip Hills AONB Unit. The nationally protected landscape of the Mendip Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) covers 198 square kilometres from Bleadon in the west to Chewton Mendip in the east. The AONB partly lies within the West of England Plan area to the south-west of the wider Bristol area and south-east of Weston-super-Mare. Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs) are some of the UK’s most cherished and outstanding landscapes.