The Rise of the Nazi Party and Its Consolidation of Power, C. 1929–34

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysing Otto Wels' Speech

Susanne Staschen-Dielmann INTERMEDIATE RANGE I: ANALYSING OTTO WELS’ SPEECH – SOURCE AND TASKS 1 Otto Wels (SPD) on the Enabling Act addressing the Annotations: Reichstag in the Kroll Opera House, 23rd March 1933 1 Meine Damen und Herren! (...) Freiheit und Leben kann man uns nehmen, die Ehre nicht. freedom and life, honour, (Lebhafter Beifall bei den Sozialdemokraten) 5 Nach den Verfolgungen, die die Sozialdemokratische Partei in der persecutions letzten Zeit erfahren hat, wird billigerweise niemand von ihr justly verlangen oder erwarten können, dass sie für das hier eingebrachte introduced Enabling Act Ermächtigungsgesetz stimmt. (...) 10 Noch niemals, seit es einen Deutschen Reichstag gibt, ist die Kontrolle der öffentlichen Angelegenheiten durch die gewählten public affairs Vertreter des Volkes in solchem Maße ausgeschaltet worden, wie eliminated es jetzt geschieht, (Sehr wahr! Bei den Sozialdemokraten) 15 und wie es durch das neue Ermächtigungsgesetz noch mehr geschehen soll. Eine solche Allmacht der Regierung muss sich um omnipotence so schwerer auswirken, als auch die Presse jeder Bewegungsfreiheit entbehrt. room for manoeuvre 20 (...) Wir sehen die machtpolitische Tatsache Ihrer augenblicklichen Herrschaft. Aber auch das Rechtsbewusstsein sense of right and wrong des Volkes ist eine politische Macht, und wir werden nicht aufhören, an dieses Rechtsbewusstsein zu appellieren. 25 Die Verfassung von Weimar ist keine sozialistische Verfassung. Aber wir stehen zu den Grundsätzen des Rechtsstaates, der state under the rule of law, Gleichberechtigung, des sozialen Rechtes, die in ihr festgelegt equal rights sind. Wir deutschen Sozialdemokraten bekennen uns in dieser admit ourselves to geschichtlichen Stunde feierlich zu den Grundsätzen der 30 Menschlichkeit und der Gerechtigkeit, der Freiheit und des humanity, justice, Sozialismus. -

Philipp-Scheidemann-Sammlung Hrsg. U. Kommentiert V. Christian

Philipp-Scheidemann-Sammlung hrsg. u. kommentiert v. Christian Gellinek I. Band. Schriften von Kassel nach Kopenhagen Münster, 2010 I. Band Abstract Dieser Eingangsband sucht den Zugang zu Philipp Scheidemanns Gesammelten Werken in der internationalen Solidarität, die von 1913-1919 zwischen den beiden sozialdemokratischen Parteien in Berlin und Kopenhagen herrschte. Europas erste sozialdemokratische Ministerpräsidenten, Philipp Scheidemann (1865-1939) und Thorvald Stauning (1873-1942), bemühten sich schon 1917, lange vor ihren Ernennungen in die höchsten Landesämter, um den europäischen Frieden. Einige unbekannte oder vergessene Dokumente aus der Stauning- Sammlung der Arbejderbevægelse Bibliotek bilden in Text, Abbildung und Karikatur eine Klammer zu Scheidemanns späterer Exilzeit 1934-39 in Kopenhagen, während derer er heimlich Ergänzungsmemoiren schrieb (vgl. III. Band) und Stauning ihn hinter den Szenen vor Gefahren seitens der Gestapo im Exil schützte. Abstract This study seeks to demonstrate an access to Scheidemanns collected works from the point of view of international solidarity between Denmark’s and Germany’s social democratic parties during 1913 to 1919, and between their two rising leaders, Philipp Scheidemann (1865-1939) and Thorvald Stauning (1873-1942). Recently, documents concerning peace initiatives in 1917/18 came to light in the Stauning Collection of the Kopenhagen Arbejderbevægelse Bibliotek. Such texts, pictures and caricatures throw new light on Stauning clandestinely protecting his friend Scheidemann’s special expatriate status as an anonymous writer in Kopenhagen (see Third Volume below) during his exile, which lasted from 1934 until his death in November, 1939. Inhaltsverzeichnis Band I I. Inhaltsverzeichnis aller vier Bände der Onlineausgabe 4 S. II. Einleitender Aufsatz „Unbekannt Gebliebenes aus Kopenhagen zu Scheidemann und Stauning“ 51 S. -

Ermächtigungsgesetze Von 1914 Bis 1933 Und Die SPD Ausarbeitung

Wissenschaftliche Dienste Ausarbeitung Ermächtigungsgesetze von 1914 bis 1933 und die SPD © 2016 Deutscher Bundestag WD 1 - 3000 - 015/14 Wissenschaftliche Dienste Ausarbeitung Seite 2 WD 1 - 3000 - 015/14 Ermächtigungsgesetze von 1914 bis 1933 und die SPD Verfasser/in: Aktenzeichen: WD 1 - 3000 - 015/14 Abschluss der Arbeit: 05.03.2014 Fachbereich: WD 1: Geschichte, Zeitgeschichte und Politik Telefon: Ausarbeitungen und andere Informationsangebote der Wissenschaftlichen Dienste geben nicht die Auffassung des Deutschen Bundestages, eines seiner Organe oder der Bundestagsverwaltung wieder. Vielmehr liegen sie in der fachlichen Verantwortung der Verfasserinnen und Verfasser sowie der Fachbereichsleitung. Der Deutsche Bundestag behält sich die Rechte der Veröffentlichung und Verbreitung vor. Beides bedarf der Zustimmung der Leitung der Abteilung W, Platz der Republik 1, 11011 Berlin. Wissenschaftliche Dienste Ausarbeitung Seite 3 WD 1 - 3000 - 015/14 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung 4 2. Verwendung des Begriffs „Ermächtigungsgesetz“ in Wissenschaft und Politik 5 3. Chronologie der Ermächtigungsgesetze 1914-1933 8 3.1. Ermächtigungsgesetz im Kaiserreich 8 3.2. Ermächtigungsgesetze der Weimarer Nationalversammlung 8 3.3. Ermächtigungsgesetze der Weimarer Republik 9 3.4. Ermächtigungsgesetz im nationalsozialistischen Deutschen Reich 12 4. Die Haltung der SPD zu den Ermächtigungsgesetzen 13 5. Quellen- und Literaturverzeichnis 15 5.1. Quellen 15 5.2. Literatur 15 Wissenschaftliche Dienste Ausarbeitung Seite 4 WD 1 - 3000 - 015/14 1. Einleitung -

When Architecture and Politics Meet

Housing a Legislature: When Architecture and Politics Meet Russell L. Cope Introduction By their very nature parliamentary buildings are meant to attract notice; the grander the structure, the stronger the public and national interest and reaction to them. Parliamentary buildings represent tradition, stability and authority; they embody an image, or the commanding presence, of the state. They often evoke ideals of national identity, pride and what Ivor Indyk calls ‘the discourse of power’.1 In notable cases they may also come to incorporate aspects of national memory. Consequently, the destruction of a parliamentary building has an impact going beyond the destruction of most other public buildings. The burning of the Reichstag building in 1933 is an historical instance, with ominous consequences for the German State.2 Splendour and command, even majesty, are clearly projected in the grandest of parliamentary buildings, especially those of the Nineteenth Century in Europe and South America. Just as the Byzantine emperors aimed to awe and even overwhelm the barbarian embassies visiting their courts by the effects of architectural splendour and 1 Indyk, I. ‘The Semiotics of the New Parliament House’, in Parliament House, Canberra: a Building for the Nation, ed. by Haig Beck, pp. 42–47. Sydney, Collins, 1988. 2 Contrary to general belief, the Reichstag building was not destroyed in the 1933 fire. The chamber was destroyed, but other parts of the building were left unaffected and the very large library continued to operate as usual. A lot of manipulated publicity by the Nazis surrounded the event. Full details can be found in Gerhard Hahn’s work cited at footnote 27. -

Die Deutsche Zentrumspartei Gegenüber Dem

1 2 3 Die Deutsche Zentrumspartei gegenüber dem 4 Nationalsozialismus und dem Reichskonkordat 1930–1933: 5 Motivationsstrukturen und Situationszwänge* 6 7 Von Winfried Becker 8 9 Die Deutsche Zentrumspartei wurde am 13. Dezember 1870 von ca. 50 Man- 10 datsträgern des preußischen Abgeordnetenhauses gegründet. Ihre Reichstagsfrak- 11 tion konstituierte sich am 21. März 1871 beim Zusammentritt des ersten deut- 12 schen Reichstags. 1886 vereinigte sie sich mit ihrem bayerischen Flügel, der 1868 13 eigenständig als Verein der bayerischen Patrioten entstanden war. Am Ende des 14 Ersten Weltkriegs, am 12. November 1918, verselbständigte sich das Bayerische 15 Zentrum zur Bayerischen Volkspartei. Das Zentrum verfiel am 5. Juli 1933 der 16 Selbstauflösung im Zuge der Beseitigung aller deutschen Parteien (außer der 17 NSDAP), ebenso am 3. Juli die Bayerische Volkspartei. Ihr war auch durch die 18 Gleichschaltung Bayerns und der Länder der Boden entzogen worden.1 19 Die Deutsche Zentrumspartei der Weimarer Republik war weder mit der 20 katholischen Kirche dieser Zeit noch mit dem Gesamtphänomen des Katho- 21 lizismus identisch. 1924 wählten nach Johannes Schauff 56 Prozent aller Ka- 22 tholiken (Männer und Frauen) und 69 Prozent der bekenntnistreuen Katholiken 23 in Deutschland, von Norden nach Süden abnehmend, das Zentrum bzw. die 24 Bayerische Volkspartei. Beide Parteien waren ziemlich beständig in einem 25 Wählerreservoir praktizierender Angehöriger der katholischen Konfession an- 26 gesiedelt, das durch das 1919 eingeführte Frauenstimmrecht zugenommen hat- 27 te, aber durch die Abwanderung vor allem der männlichen Jugend von schlei- 28 chender Auszehrung bedroht war. Politisch und parlamentarisch repräsentierte 29 die Partei eine relativ geschlossene katholische »Volksminderheit«.2 Ihre re- 30 gionalen Schwerpunkte lagen in Bayern, Südbaden, Rheinland, Westfalen, 31 32 * Erweiterte und überarbeitete Fassung eines Vortrags auf dem Symposion »Die Christ- 33 lichsozialen in den österreichischen Ländern 1918–1933/34« in Graz am 4. -

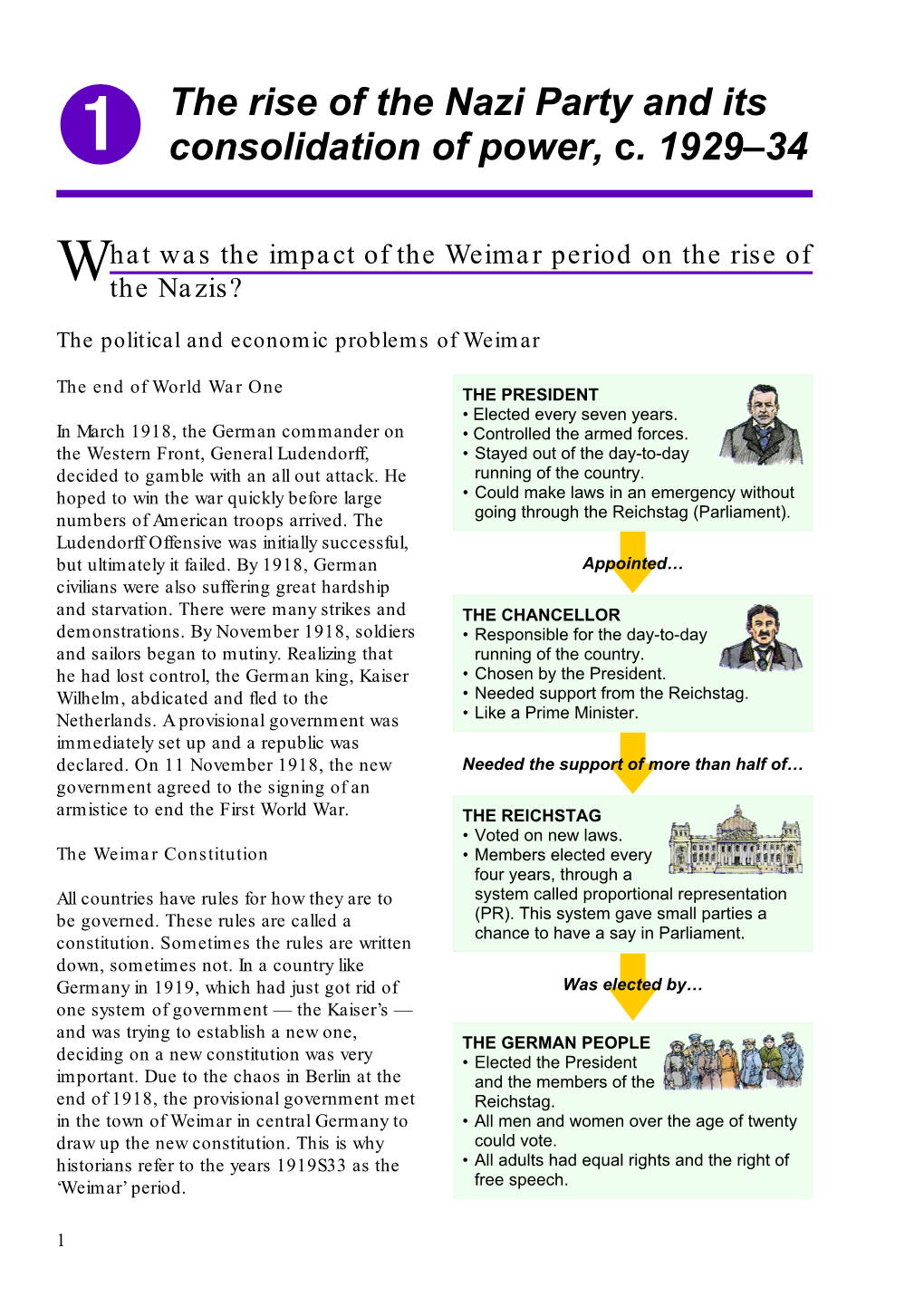

Power Distribution in the Weimar Reichstag in 1919-1933

Power Distribution in the Weimar Reichstag in 1919-1933 Fuad Aleskerov1, Manfred J. Holler2 and Rita Kamalova3 Abstract: ................................................................................................................................................2 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................2 2. The Weimar Germany 1919-1933: A brief history of socio-economic performance .......................3 3. Political system..................................................................................................................................4 3.2 Electoral system for the Reichstag ..................................................................................................6 3.3 Political parties ................................................................................................................................6 3.3.1 The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD).....................................................................7 3.3.2 The Communist Party of Germany (Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands – KPD)...............8 3.3.3 The German Democratic Party (Deutsche Demokratische Partei – DDP)...............................9 3.3.4 The Centre Party (Deutsche Zentrumspartei – Zentrum) .......................................................10 3.3.5 The German People's Party (Deutsche Volkspartei – DVP) ..................................................10 3.3.6 German-National People's Party (Deutsche -

Otto Wels Und Die Verteidigung Der Demokratie

1 Gesprächskreis Geschichte Heft 45 Manfred Stolpe Otto Wels und die Verteidigung der Demokratie Vortrag im Rahmen der Reihe „Profile des Parlaments“ der Evangelischen Akademie zu Berlin am 14. Februar 2002 Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Historisches Forschungszentrum 2 ISSN 0941-6862 ISBN 3-89892-080-1 Herausgegeben von Dieter Dowe Historisches Forschungszentrum der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Kostenloser Bezug beim Historischen Forschungszentrum der Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Godesberger Allee 149, D-53175 Bonn (Tel. 0228 - 883-473) E-mail: [email protected] © 2002 by Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Bonn (-Bad Godesberg) Umschlag: Pellens Kommunikationsdesign GmbH, Bonn Druck: Toennes Satz+ Druck GmbH, Erkrath Alle Rechte vorbehalten Printed in Germany 2002 3 Inhalt Manfred Stolpe Otto Wels und die Verteidigung der Demokratie 5 Anhang Rede von Otto Wels zum „Ermächtigungsgesetz“ auf der Sitzung des Reichstags vom 23. März 1933 29 4 5 Ministerpräsident Dr. Manfred Stolpe Otto Wels und die Verteidigung der Demokratie Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren! Es ist mir eine Ehre und Freude zugleich, heute zu Ihnen spre- chen zu dürfen, noch dazu an diesem schönen Ort. Der Gendar- menmarkt ist ein architektonisches Juwel, ein Gesamtkunstwerk, dessen Schönheit seine Besucher immer wieder aufs Neue in seinen Bann zieht - eine Kulisse, die Lust macht auf Geschichte und zum Abschweifen in vergangene Zeiten verführt. Die Vortragsreihe „Profile des Parlaments“ lädt ein zu einer Zeitreise ganz besonderer Art. Die Idee, anhand herausragender Politiker die demokratische Entwicklung Deutschlands von der Weimarer Zeit bis heute nachzuzeichnen, hat sich als überaus fruchtbar erwiesen. Politiker werfen einen Blick auf die Arbeit ihrer „Kollegen“ von einst. Entstanden ist ein Reigen interessan- ter Biografien, die eindrucksvolle Einblicke in das Funktionie- ren, aber auch das Scheitern des deutschen Parlamentarismus vermitteln. -

The Reichstag Fire Roleplay Exercise

1 The Nazi Consolidation of Power 1. Parliament: “Were the Nazis responsible for burning down the German Reichstag?” What happened? In February 1933, only a month after Hitler became Chancellor, the Reichstag Parliament building mysteriously burnt to the ground. Hitler claimed that the communists were responsible and called fresh elections. The Nazis won a record amount of seats. Hitler was now in a position to pass whatever laws he wished… Who was responsible? Some historians insist that the Nazis started the fire themselves. Others insist that the fire was started by the communists and Hitler just took advantage of it. Your Task is to investigate the evidence and reach your own conclusion on this genuine mystery. The Nazis on Trial Stage 1: Choosing your witnesses Paired Task a. Your teacher will provide a Witness Statements Sheet to each pair of students in the class. Cut these up into slips and organise them into two piles: (i) Prosecution witnesses (=blaming the Nazis for the fire); (ii) Defence Witnesses (blaming the communists). b. Decide upon three "star" witnesses in each pile. Group Task • The class will now be divided into two teams: - The PROSECUTION team will try to prove the Nazis started the fire themselves. - The DEFENCE team will try to prove that the Nazis did not start the fire. a. As a group, discuss your findings and settle upon three "star" witnesses for your side. Keep your choices secret from the other group! b. Once you are in agreement, the teacher will give a Witness Report Sheet to each group. c. -

F. Report on the Congress

F. Report on the congress Objekttyp: Group Zeitschrift: IABSE congress report = Rapport du congrès AIPC = IVBH Kongressbericht Band (Jahr): 2 (1936) PDF erstellt am: 11.10.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch REPORT ON THE CONGRESS BERICHT ÜBER DEN VERLAUF DES KONGRESSES COMPTE-RENDU DU CONGRfiS Leere Seite Blank page Page vide The ceremonial opening of the Congress took place on the morning of October lst, 1936, to the stirring strains of an overture of Beethoven, in the Reichstag Assembly Hall of the Kroll Opera House. The proceedings were opened by the President of the Congress, Dr. -

Exclusion After the Seizure of Power

Exclusion after the Seizure of Power 24 | L A W YE RS W I T H O U T R IGH T S The first Wave of Exclusion: Terroristic Attacks Against Jewish Attorneys After (Adolph) Hitler was appointed Reich Chancellor and a coalition government was formed that included German nationalists, the National Socialists increased the level of national terror. The Reichstag fire during the night of Feb. 28, 1933 served as a signal to act. It provided the motive to arrest more than 5,000 political opponents, especially Communist officials and members of the Reichstag, as well as Social Democrats and other opponents of the Nazis. The Dutch Communist Marinus van der Lubbe, who was arrested at the scene of the crime, was later sentenced to death and executed. It was for this reason that, on March 29, 1933— afterwards—a special law was enacted that increased criminal penalties, because up to then the maximum punishment for arson had been penal servitude. The other four accused, three Bulgarian Communists (among them the well-known Georgi Dimitroff) and a German Communist, Ernst Torgler, were acquitted by the Reichsgericht, the Weimar Republic’s highest court, in Leipzig. On the day of the Reichstag fire, Reich President von Hindenburg signed the emergency decree “For the Protection of the People and the State.” This so-called “Reichstag fire decree” suspended key basic civil rights: personal freedom, freedom of speech, of the press, of association and assembly, the confidentiality of postal correspondence and tele- phone communication, the inviolability of property and the home. At the beginning of February another emergency decree was promulgated that legalized “protective custody,” which then proceeded to be used as an arbitrary instrument of terror. -

The Itinerary

HARALD SANDNER HITLER THE ITINERARY Whereabouts and Travels from 1889 to 1945 VOLUME I 1889–1927 Introduction Where exactly did Hitler reside from the time of his birth on 20 April 1889 in the Austrian village of Braunau am Inn, then part of Austria-Hungary, until his suicide on 30 April 1945 in Berlin at a time when the Third Reich was almost entirely occupied? This book is a nearly exhaustive account of the German dictator’s movements, and it answers this question. It !rst o"ers a summary of all the places he lived and stayed in, as well as his travel details, in- cluding information about the modes of transport. It then puts this data in its political, military and personal/private context. Additional information relating to the type of transportation used, Hitler’s physical remains and the destruction he left behind are also included. Biographies on Hitler have researched sources dating back to the period between 1889 and 1918. Such biographers – especially in more recent times – were able to as- sess new material and correct the mistakes made by other authors in the past. Prominent examples include Anton Joachimsthaler (1989, 2000, 2003, 2004) and Brigitte Hamann (2002, 2008) ades of Hitler’s life. Hitler became politically active in 1919. Sources from the early years are scarce and relatively neutral. However, soon after that, the tone of the sources is in#uenced heav- ily by the political attitudes of contemporary journalism. Objective information waned, and reports were either glori!ed or highly disapproving. References to travel, the means of transport used, etc do exist to some degree, but are often also contradictory. -

The Enabling Act of 23 March 1933 the Political Situation in the Final Stages of the Weimar Republic Was Confusing and Unstable

HISTORICAL EXHIBITION PRESENTED BY THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ The Enabling Act of 23 March 1933 The political situation in the final stages of the Weimar Republic was confusing and unstable. Changing cabinets and coalitions and political, social and economic crises were the order of the day. Paul von Hindenburg, President of the Reich, was resorting more and more frequently to emergency decrees and dissolved the Reichstag twice in 1932. The prevailing political conditions facilitated the transition of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) from a radical splinter group to a party of government. In the two elections to the Reichstag in 1932 and in the election of 1933, which was free only on paper, the NSDAP won the largest share of the vote by far. On 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of the Reich by President Hindenburg. Hitler was thus placed at the head of a cabinet comprising non-attached Conservative ministers, members of the NSDAP and representatives of the German National People’s Party (DNVP). The direction in which the political situation would develop under Hitler became clear only shortly after he took office. The Reichstag Fire Decree (Reichstagsbrandverordnung), enacted only one day after the fire in the Reichstag building on 27 February 1933, severely curtailed fundamental rights, subjected the police largely to the control of the national government and thereby created all sorts of opportunities for the persecution and elimination of political opponents, which the police and the so- called auxiliary police forces formed by SA and SS troops exploited to the full. The next step towards the ‘Führer state’ was the abolition of parliamentary democracy and the rule of law.