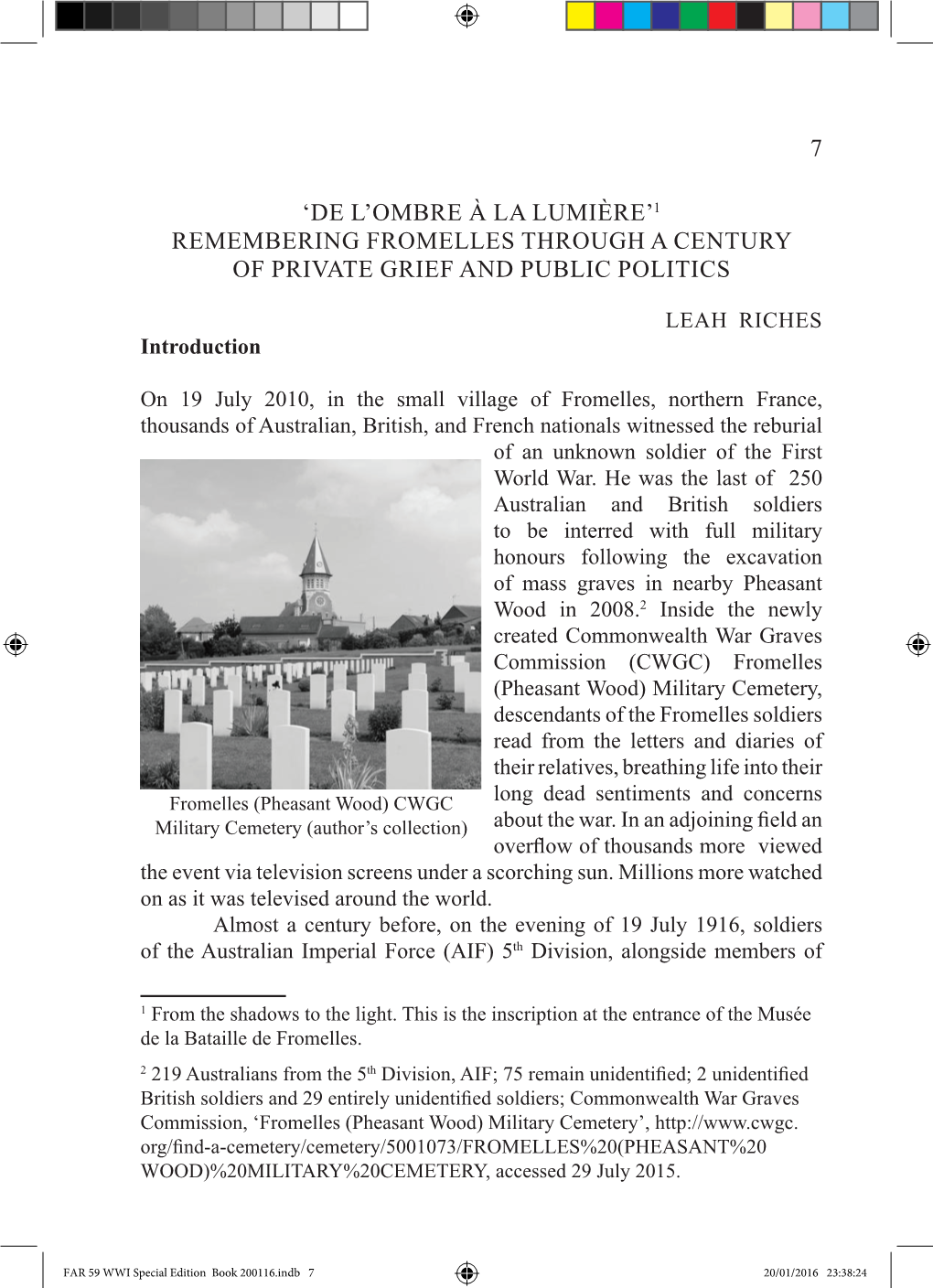

Remembering Fromelles Through a Century of Private Grief and Public Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Ed 2 June 2015 2 June Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Western Front The Western Creative Media Design ADR003970 Edition 2 June 2015 The Somme Battlefield: Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The Somme Battlefield: Lochnagar Crater. It was blown at 0728 hours on 1 July 1916. Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front 2nd Edition June 2015 ii | THE WESTERN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR ISBN: 978-1-874346-45-6 First published in August 2014 by Creative Media Design, Army Headquarters, Andover. Printed by Earle & Ludlow through Williams Lea Ltd, Norwich. Revised and expanded second edition published in June 2015. Text Copyright © Mungo Melvin, Editor, and the Authors listed in the List of Contributors, 2014 & 2015. Sketch Maps Crown Copyright © UK MOD, 2014 & 2015. Images Copyright © Imperial War Museum (IWM), National Army Museum (NAM), Mike St. Maur Sheil/Fields of Battle 14-18, Barbara Taylor and others so captioned. No part of this publication, except for short quotations, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Editor and SO1 Commemoration, Army Headquarters, IDL 26, Blenheim Building, Marlborough Lines, Andover, Hampshire, SP11 8HJ. The First World War sketch maps have been produced by the Defence Geographic Centre (DGC), Joint Force Intelligence Group (JFIG), Ministry of Defence, Elmwood Avenue, Feltham, Middlesex, TW13 7AH. United Kingdom. -

Modèle Subvention-Convention

21 C 0095 Séance du vendredi 19 février 2021 Délibération DU CONSEIL RESEAUX, SERVICES ET MOBILITE-TRANSPORTS - DECHETS MENAGERS - EXPLOITATION DES DECHETERIES METROPOLITAINES ET GESTION DE MOYENS TECHNIQUES ADAPTES POUR LA LOGISTIQUE ET L'EVACUATION DES DECHETS MENAGERS ET ASSIMILES - APPEL D'OFFRES OUVERT - DECISION - FINANCEMENT I. Rappel du contexte Parce que les générations futures nous le commandent, parce que les déchets de certains sont la ressource des autres, parce que les réglementations évoluent, la MEL doit se repositionner en tant qu’autorité compétente et collectivité exemplaire et innovante en matière de prévention et de gestion des déchets. La MEL, s'est engagée dans un programme local de prévention et veut, par son futur schéma directeur, fixer des objectifs ambitieux sur la prévention et la gestion des déchets sur l'ensemble de son territoire. Ses principaux objectifs s'appuient sur la diminution de la quantité de déchets produits, l’amélioration de la valorisation, la préservation des ressources et la réduction de leur nocivité. C’est pourquoi, au cours des prochaines années, il est nécessaire de chercher de nouvelles solutions et conduire de nouvelles actions pour « jeter moins, trier plus et mieux, moderniser le traitement des déchets ». Derrière ces problématiques, ce sont les questions d’économie sociale et solidaire, d’alimentation et de santé publique des générations futures qui sont en jeu. Les déchèteries offrent une solution pour les déchets ne pouvant être collectés de façon traditionnelle par les services de collecte des déchets du quotidien en raison de leur taille, de leur quantité ou de leur nature (exemple : dangerosité des déchets, existence d’une filière de responsabilité élargie des producteurs). -

15 Mars 2020 Etat Des Candidatures Régulièrement Enregistrées Arrond

Elections municipales et communautaires - premier tour - 15 mars 2020 Etat des candidatures régulièrement enregistrées Arrondissement de Lille Communes de moins de 1000 habitants Libellé commune Sexe candidat Nom candidat Prénom candidat Nationalité Beaucamps-Ligny F BAUGE Pascale Française Beaucamps-Ligny M BEHAREL Kilien Française Beaucamps-Ligny F BERGER Charlotte Française Beaucamps-Ligny F BOGAERT Caroline Française Beaucamps-Ligny M BONNEEL André Française Beaucamps-Ligny F DEBAECKER Noémie Française Beaucamps-Ligny F DEHAUDT Ingrid Française Beaucamps-Ligny M DEPOIX Eric Française Beaucamps-Ligny M DIGNE Eric Française Beaucamps-Ligny M DOURLOU Pascal Française Beaucamps-Ligny M DUMORTIER Tanguy Française Beaucamps-Ligny F DURREAU Cécile Française Beaucamps-Ligny M FLAVIGNY Fabrice Française Beaucamps-Ligny M FOUCART François Française Beaucamps-Ligny F GILMANT Claudine Française Beaucamps-Ligny M GUEGAN Julien Française Beaucamps-Ligny F HOUSPIE Karine Française Beaucamps-Ligny F JUMAUCOURT Bernard Française Beaucamps-Ligny F LECHOWICZ Sarah Française Beaucamps-Ligny F LEFEBVRE Catherine Française Beaucamps-Ligny M MAEKER Dominique Française Beaucamps-Ligny M MORCHIPONT Jérôme Française Beaucamps-Ligny M NONQUE Ferdinand Française Beaucamps-Ligny M PERCHE Gautier Française Beaucamps-Ligny M RENARD Ronny Française Beaucamps-Ligny M SCELERS Stéphane Française Beaucamps-Ligny M SEGUIN Antoine Française Beaucamps-Ligny F STAQUET Evelyne Française Beaucamps-Ligny F TALPE Sophie Française Beaucamps-Ligny F TOURBIER Véronique Française -

Back-Roads| Europe

WWI BATTLEFIELDS Blue-Roads | Europe This fascinating and moving tour focuses on the major areas of British and Commonwealth involvement across the Western Front – from The Somme to Flanders. Providing guests with a level of flexibility to visit memorials to his (or her) country’s fallen, and the expert knowledge of our Tour Leaders – this tour promises to be as unforgettable as it is enlightening. TOUR CODE: BEWBFLL-1 Thank You for Choosing Blue-Roads Thank you for choosing to travel with Back-Roads Touring. We can’t wait for you to join us on the mini-coach! About Your Tour Notes THE BLUE-ROADS DIFFERENCE Have the opportunity to pay your respects at your relatives’ graves with These tour notes contain everything you need to know visits to significant sites before your tour departs – including where to meet, Receive a fascinating insight into the what to bring with you and what you can expect to do lives of WWI soldiers at the on each day of your itinerary. You can also print this Underground City of Naours document out, use it as a checklist and bring it with you Attend the playing of the Last Post on tour. under the famous Menin Gate in Ypres Please Note: We recommend that you refresh this document one week before your tour TOUR CURRENCIES departs to ensure you have the most up-to-date accommodation list and itinerary information + France - EUR available. + Belgium - EUR Your Itinerary DAY 1 | LILLE After meeting the group in Lille, we’ll kick off our battlefields tour with a delicious welcome dinner. -

LISTE-DES-ELECTEURS.Pdf

CIVILITE NOM PRENOM ADRESSE CP VILLE N° Ordinal MADAME ABBAR AMAL 830 A RUE JEAN JAURES 59156 LOURCHES 62678 MADAME ABDELMOUMEN INES 257 RUE PIERRE LEGRAND 59000 LILLE 106378 MADAME ABDELMOUMENE LOUISA 144 RUE D'ARRAS 59000 LILLE 110898 MONSIEUR ABU IBIEH LUTFI 11 RUE DES INGERS 07500 TOURNAI 119015 MONSIEUR ADAMIAK LUDOVIC 117 AVENUE DE DUNKERQUE 59000 LILLE 80384 MONSIEUR ADENIS NICOLAS 42 RUE DU BUISSON 59000 LILLE 101388 MONSIEUR ADIASSE RENE 3 RUE DE WALINCOURT 59830 WANNEHAIN 76027 MONSIEUR ADIGARD LUCAS 53 RUE DE LA STATION 59650 VILLENEUVE D ASCQ 116892 MONSIEUR ADONEL GREGORY 84 AVENUE DE LA LIBERATION 59300 AULNOY LEZ VALENCIENNES 12934 CRF L'ESPOIR DE LILLE HELLEMMES 25 BOULEVARD PAVE DU MONSIEUR ADURRIAGA XIMUN 59260 LILLE 119230 MOULIN BP 1 MADAME AELVOET LAURENCE CLINIQUE DU CROISE LAROCHE 199 RUE DE LA RIANDERIE 59700 MARCQ EN BAROEUL 43822 MONSIEUR AFCHAIN JEAN-MARIE 43 RUE ALBERT SAMAIN 59650 VILLENEUVE D ASCQ 35417 MADAME AFCHAIN JACQUELINE 267 ALLEE CHARDIN 59650 VILLENEUVE D ASCQ 35416 MADAME AGAG ELODIE 137 RUE PASTEUR 59700 MARCQ EN BAROEUL 71682 MADAME AGIL CELINE 39 RUE DU PREAVIN LA MOTTE AU BOIS 59190 MORBECQUE 89403 MADAME AGNELLO SYLVIE 77 RUE DU PEUPLE BELGE 07340 colfontaine 55083 MONSIEUR AGNELLO CATALDO Centre L'ADAPT 121 ROUTE DE SOLESMES BP 401 59407 CAMBRAI CEDEX 55082 MONSIEUR AGOSTINELLI TONI 63 RUE DE LA CHAUSSEE BRUNEHAUT 59750 FEIGNIES 115348 MONSIEUR AGUILAR BARTHELEMY 9 RUE LAMARTINE 59280 ARMENTIERES 111851 MONSIEUR AHODEGNON DODEME 2 RUELLE DEDALE 1348 LOUVAIN LA NEUVE - Belgique121345 MONSIEUR -

The Anzacs and Australian Identity – Jill Curry Australian Curriculum, Year 9 – ACDSEH095, ACDSEH097, ACHHS172 Year 8 ACHCK0

The ANZACs and Australian Identity – Jill Curry Australian Curriculum, Year 9 – ACDSEH095, ACDSEH097, ACHHS172 Year 8 ACHCK066 F-10 Humanities and Social Sciences/Key Ideas/Who we are...values that have shaped societies The ANZACs who joined the Australian Imperial Forces were all volunteers. The people who enlisted were willing to leave their families, homes, jobs and friends to serve in a foreign country in a war that was not even threatening their own country or livelihood. From a population of less than five million at the time, Australia had 416,809 men voluntarily enlist in World War I. Of these, 332,000 served overseas. Over 60,000 died and 156,000 were wounded, taken prisoner or gassed. From the total, 32,000 men and 40,000 horses participated in the Palestinian campaign which claimed 1,394 dead from injuries or disease and 4,851 wounded.1 Almost half of all New Zealand’s eligible men enlisted. Sacrifice John Simpson Kirkpatrick served in the field ambulance at Gallipoli as part of the Australian Imperial Forces Medical Corps. He is renowned for working day and night carrying the injured on his donkey from Monash Valley down to Anzac Cove. He was fearless in the face of bullets and machine guns, thinking not of his own safety but only those who were injured. He was only 22 years old when he finally succumbed to the deadly fire and is buried in Gallipoli. Another who paid the ultimate price was Australian cricketer Albert ‘Tibby’ Cotter. He was in the 12th Light Horse regiment serving as a stretcher-bearer on the day of the battle of Beersheba. -

British 8Th Infantry Division on the Western Front, 1914-1918

Centre for First World War Studies British 8th Infantry Division on the Western Front, 1914-18 by Alun Miles THOMAS Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law January 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Recent years have seen an increasingly sophisticated debate take place with regard to the armies on the Western Front during the Great War. Some argue that the British and Imperial armies underwent a ‘learning curve’ coupled with an increasingly lavish supply of munitions, which meant that during the last three months of fighting the BEF was able to defeat the German Army as its ability to conduct operations was faster than the enemy’s ability to react. This thesis argues that 8th Division, a war-raised formation made up of units recalled from overseas, became a much more effective and sophisticated organisation by the war’s end. It further argues that the formation did not use one solution to problems but adopted a sophisticated approach dependent on the tactical situation. -

Contacts : Accueil De Loisirs À Le Maisnil Mairies : Directrice : Anne

Rappel : En cas d’annulation d’un repas ou d’une journée, vous devez prévenir Accueil de Loisirs En partenariat avec les communes d’Aubers, la direction au moins 48 heures à l’avance. Dans le cas contraire, les prestations Intercommunal Fromelles, Le Maisnil et Radinghem-en-Weppes seront facturées, à l’exception d’un cas de force majeure (un certificat médical ou autre sera demandé) Contacts : Accueil de Loisirs à Le Maisnil Foyer Rural, Rue de l’Eglise 59134 Le Maisnil Mairies : Aubers : 03.20.50.20.38 Fromelles : 03.20.50.20.43 Le Maisnil : 03.20.50.24.11 Radinghem : 03.20.50.24.18 Directrice : Anne Tibaux 06.86.07.19.91 Mail : [email protected] ILEP NORD 3 rue des Bois Blancs 59320 Radinghem-en-Weppes 06.86.07.19.91 / [email protected] IPNS Vacances, j’oublie tout ! ATTENTION !!! Les dossiers sont à renouveler cette année sauf si votre enfant a fréquenté les centres de la toussaint Enfin presque tout ! Il faut bien penser à s’amuser un peu !!! Et à créer, inventer et de Noël ! Vous pouvez les retirer dans votre mairie, ils sont à remplir et à nous remettre lors de et partager ! Surtout n’hésite pas à nous rejoindre pour profiter de toutes ces l’inscription de votre enfant : AVANT LE 13 FEVRIER 2012 IMPERATIVEMENT ! activités et avec un peu de chance, la neige sera au rendez-vous pour encore plus d’amusement ! A très vite… Horaires de l’accueil de loisirs L’accueil sera ouvert du lundi 27 février au vendredi 9 mars 2012 Journée TARIFS Garderie matin 7h30-9h00 9h00-17h00 avec repas Journée 9h00-12h00 5 jours Garderie soir 17h00-18h30 Barème QF CAF Journée sans repas 14h00-17h00 continus 1 0 à 266 3,20€ 16€ 2 267 à 381 5€ 25€ Bulletin à remettre en mairie avant le 13 février 2012 DERNIER DELAI 3 382 à 533 7€ 30€ accompagné de votre règlement à l’ordre d’ILEP Nord et d’un dossier complet que vous aurez préalablement retiré en mairie 4 534 à 762 9€ 38€ Accueil de Loisirs /Vacances d’Hiver 2012 5 763 à 914 11€ 47€ 6 915 et + 12,50€ 53€ Nom et prénom(s) de(s) l’enfant(s)………………………………………………………………………………………………… Age(s) …………………………………………………………….... -

Périmètres De Protection Des Captages D'alimentation En Eau

Préfecture du NORD - DDASS du Nord - DRDAF du Nord SITE_179 Périmètres de Protection des Captages d'Alimentation en Eau Potable Liste des Périmètres de Protections concernés par le site Communes concernées ou limitrophes du site Informations transmises à la demande par la DDASS du Nord. CODE_PPC SURF_ha SAISE CODE_INSEE NOM_COM Légende : PPI 0,022 à vue 59005 Allennes-les-Marais Données transmises à titre informatif, ne se substituant pas - Captage & N° BSS PPI 0,026 à vue 59011 Annœullin aux Arrêtés préfectoraux en vigueur (DUP / annexes / plans). PPI = Périmètre de Protection Immédiat PPI 0,018 à vue 59193 Emmerin PPI 0,031 à vue 59266 Gondecourt Sources des données : DDASS 59 / DDAF 59 / BRGM PPR = Périmètre de Protection Rapproché PPI 0,031 à vue 59286 Haubourdin Référentiels cartographiques : PPIGE www.ppige-npdc.fr PPE = Périmètre de Protection Eloigné PPI 0,034 à vue 59304 Herrin (I2G : orthophotoplan 2006 / IGN : Scan25, BD Parcellaire) Saisie & réalisation : DDASS59(CD/JC) & DRDAF(PFY/JPR/FM) Autres sites PPI 0,023 à vue 59316 Houplin-Ancoisne Zonage non ou mal renseigné PPI 0,031 à vue 59437 Noyelles-lès-Seclin Version JANVIER 2009 PPI 0,157 BP 59524 Sainghin-en-Weppes PIG = Projet d'Intérêt Général PPI 0,113 BP 59553 Santes PPI 0,105 BP 59560 Seclin EnglosEnglos PPI 0,109 BP 59648 Wattignies EscobecquesEscobecques SequedinSequedin PPI 0,222 BP 59653 Wavrin LeLe MaisnilMaisnil PPI 0,108 BP 59670 Don PPI 0,126 BP Erquinghem-le-SecErquinghem-le-Sec Erquinghem-le-SecErquinghem-le-Sec PPI 0,066 BP PPI 0,078 BP PPI 0,093 BP LilleLille -

Reveille – November 2020

Reveille – November 2020 Reveille – No.3 November 2020 The magazine of Preston & Central Lancashire WFA southribble-greatwar.com 1 Reveille – November 2020 In Flanders fields the poppies blow Between the crosses, row on row, That mark our place; and in the sky The larks, still bravely singing, fly Scarce heard amid the guns below. We are the Dead. Short days ago We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow, Loved and were loved, and now we lie, In Flanders fields. Take up our quarrel with the foe: To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields. John McCrae Cover photograph by Charlie O’Donnell Oliver at the Menin Gate 2 Reveille – November 2020 Welcome… …to the November 2020 edition of our magazine Reveille. The last few months have been difficult ones for all of us particularly since we are not able to meet nor go on our usual travels to the continent. In response the WFA has been hosting a number of online seminars and talks – details of all talks to the end of the year and how they can be accessed are reproduced within this edition. The main theme of this edition is remembrance. We have included articles on various War Memorials in the district and two new ones this branch has had a hand in creating. The branch officers all hope that you are well and staying safe. We wish you all the best for the holiday season and we hope to meet you again in the new year. -

Doc Préparatoire Débat PADD PLU Weppes

Révision générale des PLU communaux Aubers, Bois-Grenier, Fromelles, Le Maisnil, Radinghem-en-Weppes Communication au conseil de la Métropole en vue des débats sur les orientations générales des Projets d’Aménagement et de Développement Durables (PADD) Synthèse du diagnostic à l’échelle des 5 communes Conseil métropolitain du 19 Octobre 2018 1 Révision générale des PLU communaux de Aubers, Bois-Grenier, Fromelles, Le Maisnil, Radinghem- en-Weppes – Document support aux débats d’orientations générales des PADD – Synthèse diagnostic BESOINS EN HABITAT 1. Dynamiques démographiques du territoire 1.1 Evolution démographique 6009 habitants à l’échelle des 5 communes en 2014, soit 0,53% de la population de la MEL, avec dans l’ordre : Bois-Grenier 1563 habitants, Aubers 1562 habitants, Radinghem-en-Weppes 1358 habitants, Fromelles 885 habitants, Le Maisnil 641 habitants. Une dynamique démographique plus soutenue qu’à l’échelle de la métropole. La population des 5 communes a quasiment doublé depuis la fin des années 1960. Cette croissance s’atténue ces dernières années (+4% entre 2009 et 2014). Evolution démographique des communes entre 1968 et 2014, base 100 en 1968 Source : INSEE, RGP 260 240 220 200 180 160 140 120 100 1968 1975 1982 1990 1999 2009 2014 2020 (estimation) Aubers Bois Grenier Fromelles Le Maisnil Radinghem-en-Weppes 5 communes MEL 2020 1968 1975 1982 1990 1999 2009 2014 (estimation) Population 3079 3576 4534 5374 5636 5761 6009 6585 Evolution de la population x 16% 27% 19% 5% 2% 4% 10% en % Une croissance alimentée par des soldes naturel et migratoire positifs. Le solde migratoire n’a été négatif que durant la période 1999-2009, contrairement à la MEL, qui a connu un solde migratoire négatif sur toute la période. -

Walk in the Footsteps of Their Elders, and in So Doing to Learn More About Their Own History

REMEMBRANCE toURISM SITES 14-18 IN SOMME SOMME WESTERN FRONT 14-18 WALK IN THE FOOTSTEPSour OF History ATOUT FRANCE 1 MINEFI TONS RECOMMANDÉS (4) MIN_11_0000_RdVFrance_Q Date le 22/06/2011 A NOUS RETOURNER SIGNÉE AVEC VOTRE ACCORD OU VOS CORRECTIONS CYAN MAGENTA JAUNE NOIR JFB ACCORD DATE CRÉATION ÉCHELLE 1/1 - FORMAT D’IMPRESSION 100% PRODUCTION CONSULTANT 12345678910 CLIENT + QUALITÉ* CARRÉ NOIR - 82, bd des Batignolles - 75017 Paris - FRANCE / Tél. : +33 (0)1 53 42 35 35 / Fax : +33 (0)1 42 94 06 78 / Web : www.carrenoir.com JEAN-MARC TODESCHINI SECretarY OF State FOR VETERANS AND REMEMBRANCE Since 2014, France has been fully engaged in the centenary of the Great War, which offers us all the opportunity to come together and share our common history. A hundred years ago, in a spirit of brotherhood, thousands of young soldiers from Great Britain and the countries of the Commonwealth came here to fight alongside us on our home soil. A century later, the scars left on the Somme still bear testimony to the battles of 1916, as do the commemorative sites which attest France’s gratitude to the 420,000 British soldiers who fell in battle, thousands of whom sacri- ficed their lives for this country. In the name of this shared history, whose echo still resonates across the landscape of the Somme, of the brothe- rhood of arms created in the horror of the trenches, and of the memory shared by our two countries, France has a duty to develop and protect the British monuments and cemeteries located in the Somme as well as to extend the warmest possible welcome to tourists visiting the region to reminisce the tragic events of the past century.