Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title Living History Circle (group interview): Out in the Redwoods, Documenting Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender History at the University of California, Santa Cruz, 1965-2003 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05d2v8nk Author Reti, Irene H. Publication Date 2004-04-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California LIVING HISTORY CIRCLE This group living history circle was conducted on April 20, 2002, as part of the Banana Slug Spring Fair annual event for UCSC alumni and prospective students. The session was organized by Irene Reti, together with Jacquelyn Marie, and UCSC staff person and alum Valerie Jean Chase. The discussion was approximately ninety minutes and included the following participants: Walter Brask, Melissa Barthelemy, Valerie Chase, Cristy Chung, James K. Graham, Linda Rosewood Hooper, Rik Isensee, David Kirk, Stephen Klein, John Laird, Jacquelyn Marie, Robert Philipson, Irene Reti, and John Paul Zimmer. This was also the thirtieth reunion of the Class of 1972, which is why there is a disproportionate number of participants from that period of UCSC history. The interview was taped and transcribed. Where possible, speakers are identified.—Editor. Jacquelyn Marie: We have three basic questions, and they will probably blend together. Please say your name, what college you graduated from, and your year of graduation. Then there should be lots of time to respond to each other. The questions have to do with Living History Circle 159 the overall climate on campus; professors and other role models, and classes; and the impact of UCSC on yourselves as GLBT people in terms of your life, your identity, your work. -

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work

UC Santa Cruz Other Recent Work Title Helene Moglen and the Vicissitudes of a Feminist Administrator Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7fc7q3z8 Authors Moglen, Helene Reti, Irene Regional History Project, UCSC Library Publication Date 2013-06-03 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7fc7q3z8#supplemental eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California University of California, Santa Cruz University Library Helene Moglen and the Vicissitudes of a Feminist Administrator Interviewed and Edited by Irene Reti Santa Cruz 2013 This manuscript is covered by copyright agreement between Helene Moglen and the Regents of the University of California dated May 28, 2013. Under “fair use” standards, excerpts of up to six hundred words (per interview) may be quoted without the University Library’s permission as long as the materials are properly cited. Quotations of more than six hundred words require the written permission of the University Librarian and a proper citation and may also require a fee. Under certain circumstances, not-for-profit users may be granted a waiver of the fee. For permission contact: Irene Reti [email protected] or Regional History Project, McHenry Library, UC Santa Cruz, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, CA, 95064. Phone: 831-459-2847 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction i Early Life 1 Bryn Mawr 6 Marriage and Family 9 Graduate Study at Yale University 12 Sig Moglen 18 Teaching at New York University 19 Teaching at State University of New York [SUNY], Purchase 26 Coming to UC -

2017-2018 Academic Year 02

CELEBRATING THE HUMANITIES 2017-2018 Academic Year 02 LETTER FROM THE DEAN TYLER STOVALL As we come to the end of another academic year, many of us are no doubt grateful for the relative calm we have experienced since last year. National politics remains turbulent, but there have been no new changes or transitions comparable to those of a year ago. If last year was a time of drama, this has been more one of reassessment and new beginnings. It has been my pleasure to welcome new colleagues to the Humanities Division. History of Consciousness has two new faculty, Banu Bargu and Massimiliano Tomba, whose presence has brought new dynamism to the department. Ryan Bennett and Amanda Rysling joined the Linguistics department as assistant professors. I’m also pleased to welcome Literature professor Marlene Tromp, who so wanted to join us she consented to accept an administrative position as Campus Provost/Executive Vice Chancellor! At the same time, I must say farewell to some valued colleagues. Professors Tyrus Miller and Deanna Shemek are moving to faculty positions at UC Irvine, where Tyrus will also serve as Dean of the Humanities. Professors Bettina Aptheker, Jim McCloskey, and Karen Tei Yamashita retired from the university, although I hope they will remain active as emeriti faculty. Finally, I must acknowledge and mourn the passing of professor emeritus Hayden V. White. One of the most renowned and influential faculty members at UC Santa Cruz, Hayden White left a rich legacy to History of Consciousness, the Humanities, and UC Santa Cruz in general. This has also been a year of new initiatives. -

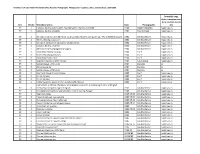

UA 128 Inventory Photographer Neg Slide Cs Series 8 16

Inventory: UA 128, Public Information Office Records: Photographs. Photographer negatives, slides, contact sheets, 1980-2005 Format(s): negs, slides, transparencies (trn), contact sheets Box Binder Title/Description Date Photographer (cs) 39 1 Campus, faculty and students. Marketing firm: Barton and Gillet. 1980 Robert Llewellyn negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Paul Schraub negatives, cs 39 2 Set construction; untitled Porter sculpture (aka"Wave"); computer lab; "Flying Weenies"poster 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Tennis, fencing; classroom 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Bike path; computers; costumes; sound system; 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Campus, faculty, students 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 2 Admissions special programs (2 pages) 1984 Jim MacKenzie negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown family housing 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Student family apartments 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Downtown Santa Cruz 1984 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Special Collections, UCSC Library 1984 Lucas Stang negatives, cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Childcare center 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 Sailing classes, UCSC dock 1984 Dan Zatz cs 39 3 East Field House; Crown College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Porter College 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs 39 3 Performing Arts; Oakes; Porter sculpture (The Wave) 1985 Joe ? negatives, cs Jack Schaar, professor of politics; Elena Baskin Visual Arts, printmaking studio; undergrad 39 3 chemistry; Computer engineering lab -

Angela Davis Bibliography Vice-Presidential Candidate, Communist Party USA (CPUSA), 1980, 1984

Angela Davis Bibliography Vice-Presidential Candidate, Communist Party USA (CPUSA), 1980, 1984 Primary Speeches Address to the Feminist Values Forum. Austin, Texas, May 1996. Excerpts available at http://www.feminist.com/resources/artspeech/family/ffvfdavis.htm (11 August 2011). Address delivered on the 40th Anniversary of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Assassination. Vanderbilt University, 2008. Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g45mEgIdxZs&feature=related (11 August 2011). “Angela Davis Speaks Out.” Alternative Views # 298. Produced by Frank Morrow. Alternative Information Network, February 1985. Video available at http://www.archive.org/details/AV_298-ANGELA_DAVIS_SPEAKS_OUT (11 August 2011). “Angela’s Homecoming.” Speech following release from prison. Embassy Auditorium. Los Angeles: Pacifica Radio Archive, 1972. “Black History Month Convocation.” Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University, 1979. Florida Memory—State Library & Archives of Florida. Video available at http://www.floridamemory.com/PhotographicCollection/video/video.cfm?VID=5 9 (11 August 2011). “Black Women in America.” UCLA Black Women’s Spring Forum Address, April 12, 1974. Broadcast on KPFK, July 8, 1974. Los Angeles: Pacifica Radio Archive, 1974. “Blues Legacies and Black Feminism.” The Power of African American Women Disc 3. Pacifica Radio Archives. Santa Monica, CA, March 1998. Available at http://www.archive.org/details/pra_powerofafricanamericanwomen_3 (11 August 2011). “How Does Change Happen?” University of California, Davis, October 10, 2006. Available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pc6RHtEbiOA&feature=related (11 August 2011). “The Liberation of Our People.” DeFremery Park, Oakland, CA, November 12, 1969. Transcript available at http://www.indybay.org/newsitems/2009/04/15/18589458.php. 2008 Video of Public reenactment available online at http://www.archive.org/details/The_Liberation_of_Our_People_Angela_Davis_1 969_2008 (11 August 2011). -

RPAATH As a Tool for Recovering and Preserving UCSC's Black Cultural

RPAATH as a Tool for Recovering and Preserving UCSC’s Black Cultural Memory and Prominence from 1967-1980s. Slides by Moses J. Massenburg UCSC, Class of 2010. Bettina Aptheker and Moses Massenburg at the Purpose(s) of Today’s Talk • Contextualize UCSC within several social and academic movements for the liberation of Black people from different forms of oppression. (Black Power, Black Studies Movement, Black Feminist Thought, Civil Rights, Black Arts, Black Student Movement, etc.) • Articulate RPAATH as an interpretive space for the Study of African American Life and History. • Empower Black Students and their antiracist allies. Overview of Black History Month and the Early Black History Movement. • Organized by Historian Carter G. Woodson’s Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH) founded Chicago in 1915. • Black History Month Started in 1926 as Negro History Week. • The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) is still active today. Woodson Home Office • Served as a meeting place for activists and community organizers. • Clearing house for the professional study of Black History. • Nurtured Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Mary McLeod Bethune, Angela Davis, and thousands of other Black innovators. Rosa Parks • Who was Rosa Parks? Answer without thinking about a public transportation, the Civil Rights Movement, or elderly persons. • Training Group at the Highlander Folk School, SUMMER 1955, Desegregation workshop six months before the Montgomery Bus Boycott began. • Founded in 1932, the school continues to operate. Visit Highlandercenter.org Recommended Reading Published in 2013 Published in 2009 What does Rosa Parks have to do with UC Santa Cruz? Septima P. -

CALIFORNIA RED a Life in the American Communist Party

alifornia e California Red CALIFORNIA RED A Life in the American Communist Party Dorothy Ray Healey and Maurice Isserman UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS PRESS Urbana and Chicago Illini Books edition, 1993 © 1990 by Oxford University Press, Inc., under the title Dorothy Healey Remembers: A Life in the American Communist Party Reprinted by arrangement with Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, New York Manufactured in the United States of America P54321 This book is printed on acidjree paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Healey, Dorothy. California Red : a life in the American Communist Party I Dorothy Ray Healey, Maurice Isserman. p. em. Originally published: Dorothy Healey remembers: a life in the American Communist Party: New York: Oxford University Press, 1990. Includes index. ISBN 0-252-06278-7 (pbk.) 1. Healey, Dorothy. 2. Communists-United States-Biography. I. Isserman, Maurice. II. Title. HX84.H43A3 1993 324.273'75'092-dc20 [B] 92-38430 CIP For Dorothy's mother, Barbara Nestor and for her son, Richard Healey And for Maurice's uncle, Abraham Isserman ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work is based substantially on a series of interviews conducted by the UCLA Oral History Program from 1972 to 1974. These interviews appear in a three-volume work titled Tradition's Chains Have Bound Us(© 1982 The Regents of The University of California. All Rights Reserved. Used with Permission). Less formally, let me say that I am grateful to Joel Gardner, whom I never met but whose skillful interviewing of Dorothy for Tradition's Chains Have Bound Us inspired this work and saved me endless hours of duplicated effort a decade later, and to Dale E. -

The Professors: the 101 Most Dangerous Academics in America

Facts Count An Analysis of David Horowitz’s The Professors: The 101 Most Dangerous Academics in America Free Exchange on Campus May 2006 Facts Count | “It is more important to teach students how to think than what to think.” -Professor Marc Becker, one of the “0 Most Dangerous Academics in America” | Facts Count EXECUTIVE SUMMARY his report examines David Horowitz’s book, The Professors: The 101 Most Dangerous Academics in America (Regnery, 2006), which brings up 101 academics on charges of Tindoctrinating their students with their political views. Since Mr. Horowitz’s charges are aimed at the core of professors’ professional ethics, we believe that they are not to be taken lightly. For Mr. Horowitz to accuse a single person of these charges—let alone 101— a reasonable person might expect him to do three things: examine the facts objectively, support his conclusions with sound evidence, and make recommendations that are in students’ best interests. We believe that Mr. Horowitz fails on all of these counts. After conducting interviews with the professors in Mr. Horowitz’s book and fact-checking Mr. Horowitz’s evidence, the Free Exchange on Campus coalition has drawn the following conclusions: • Mr. Horowitz’s book condemns professors for actions that are entirely within their rights and entirely appropriate in an atmosphere that promotes the free exchange of ideas. Mr. Horowitz chiefly condemns professors for expressing their personal political views outside of the classroom. He provides scant evidence of professors’ in-class behavior and fails to substantiate his charge that the professors in his book indoctrinate their students. -

Locations with Resources and Accessions

Locations with Resources and Accessions Number of Results: 26 McHenry Library Floor: Ground Room: Media Center Area: Media Center cage Coordinates: UA Accession Title Accession Number Shakespeare Santa Cruz records, 3rd accrual 2014.012 McHenry Library Floor: 1 Room: 1116 Coordinates: UA McHenry Library Floor: 1 Room: 1170 Area: Flat file Coordinates: Flat file Accession Title Accession Number George Hitchcock Papers 1984.002 McHenry Library Floor: 1 Room: 1170 Coordinates: MS Accession Title Accession Number War Ephemera Collection 2010.017 Helen Hyde Woodcuts, 1903-1914 1991.002 Robert A. and Virginia G. Heinlein papers, accrual 2014.23 2014.023 Earle and Akie Reynolds Archive 1995.003 Byron Stookey Letters 1967.007 Nicholas Mayall papers 1971.003 Sawyer Postcard Collection 1965.030 Kenneth Patchen Papers 1975.003 Fisher & Hughes Productions records 2012.011 Morton Marcus Poetry Archive 2010.001 Locations with Resources and Accessions December 17, 2015 Page 2 of 33 McHenry Library Floor: 1 Room: 1170 Coordinates: UA Accession Title Accession Number UCSC Poster Collection 1965.040 Diaries, ledgers and scrapbooks collection 2013.002 McHenry Library Floor: 1 Room: 1221 Coordinates: MS Accession Title Accession Number Anna Gayton Collection 1965.083 Santa Cruz Woman's Club records, accession 2015.026 2015.026 Tom Millea photographs 1996.012 Lou Harrison Papers: Music Manuscripts 1993.003.1 Charles A. McLean Papers 1982.006 Karen Tei Yamashita Papers, June 2015 accrual 2015.017 Walsh Family Papers 1998.011 Edith M. Shiffert papers, accrual 2015.008 2015.008 Trianon Press Archive 1983.006 California Federation of Women's Clubs Records 1983.001 Sawyer Family Papers 1964.001 Colin Fletcher papers 1994.009 Steve Crouch photographs 1994.001 "Uncle Sam" Bobble-Head, San Francisco Giants Jerry Garcia Day 2013.010 Commemorative, 2013. -

AMERICAN STUDIES PROGRAM PROPOSAL for SUMMER 2011 RESEARCH GRANT Program Objective the Core of the Summer Research Program Is To

AMERICAN STUDIES PROGRAM PROPOSAL FOR SUMMER 2011 RESEARCH GRANT Program Objective The core of the Summer Research Program is to employ students as research assistants for faculty scholars. These positions will match students and faculty according to research interests and will be intended to support the student’s development of an understanding of the techniques of intellectual inquiry and research. Recruitment Faculty affiliated with American Studies will be invited to take advantage of this opportunity to work with an undergraduate research assistant and interested students will be encouraged to apply. The Director of the program will facilitate matching students with appropriate mentors. The American Studies Program has offered successful Summer Research Programs since 2002 and hopes to continue making this valuable opportunity available to students and faculty. Student Responsibilities The expectation is that the student will work approximately 30 hours per week on specific tasks assigned by the faculty member, and another 10 hours per week pursuing the student’s own related academic interest with the faculty member’s guidance. For some students, this may be preliminary research for an honors thesis in American Studies. For others the exposure to faculty research may foster interest in future graduate study. Mentoring Oversight of the program is provided by the Director of American Studies, Shelley Fisher Fishkin, who will be in contact with the faculty advisers, monitoring that the program guidelines are being met and that each student-faculty research team understands and are in compliance with the guidelines. Faculty will meet individually with the student assistants, meeting with them regularly and providing direction and feedback. -

A Review of Bettina Aptheker's Morning Breaks

The Black Scholar Journal of Black Studies and Research ISSN: 0006-4246 (Print) 2162-5387 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rtbs20 Book Reviews Joy James, John Woodford & Michael Nash To cite this article: Joy James, John Woodford & Michael Nash (2002) Book Reviews, The Black Scholar, 32:1, 52-57, DOI: 10.1080/00064246.2002.11431170 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00064246.2002.11431170 Published online: 14 Apr 2015. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 14 Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rtbs20 THEBLACKSCHOLAR BOOK REVIEWS THE MORNING BREAKS: THE TRIAL OF HERE ARE MANY INTERESTING STORIES woven into ANGELA DAVIS, by Bettina Aptheker. (lthaca, T The Morning Breaks. Aptheker recalls the NY: Cornell University Press, 1999), 294 pp., adverse impact the trial had on her family. (Just as $16.95, paper. Reviewed ffyjay]ames Davis had seen her UCLA contract as an Assistant Professor in philosophy terminated because of FTEN, CONVENTIONAL ACCOUNTS of democratic her open membership in the Communist Party, O struggle sweep the most violent and unsa Aptheker's then-husband Jack Kurzweil would be vory aspects of U .S. history under the rug. At denied tenure at San Francisco State because of times, though, important works that deepen our the couple's highly visible role in Davis's defense understanding of contemporary battles for social team-a court later reversed the termination). justice in the United States surface. Providing a There are accounts of courage, venality, tragedy corrective to political amnesia, Bettina Aptheker and eventually triumph surrounding one of the offers a provocative and incisive narrative in The most massive and successful campaigns in twenti Morning Breaks. -

The Berkeley Free Speech Movement and the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission

The Berkeley Free Speech Movement and the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission On Thursday, August 18, 1966 I entered the Bellflower Church in Grenada, Mississippi, which the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was using as its headquarters for a voter registration project. I had been a field- worker for SCLC for over a year but in Mississippi only since June. As soon as I walked through the door, the other workers asked me if I had seen that morn- ing's Jackson Daily News. I quickly discovered that "Mississippi's Greatest Newspaper," as it called itself, had devoted two-thirds of its editorial page to an expose of my activities, mostly during my senior year at the University of California at Berkeley. "Professional Agitator Hits All Major Trouble Spots" blared the headline. It was accompanied by five photos - front, side, hair up and hair down, with and without glasses - including one taken of me speaking from the second floor balcony of Sproul Hall during the big student sit-in on December 3, 1964, which resulted in 773 arrests. Citing the 1965 report of the California Senate's Factfinding Subcommittee on UnAmerican Activities (SUAC) as its primary source, the editorial didn't call me a Communist. It said I worked with Communists (Bettina Aptheker, a Berkeley student who admit- ted her Party membership in November 1965, six months after I graduated) and was a member of a student organization for young Communists (SLATE, a leftylliberal student group that was not Communist). It also informed its read- ers that I was "active in the Free Speech Movement" (true) and a "sparkplug in the Filthy Speech Movement" (false).