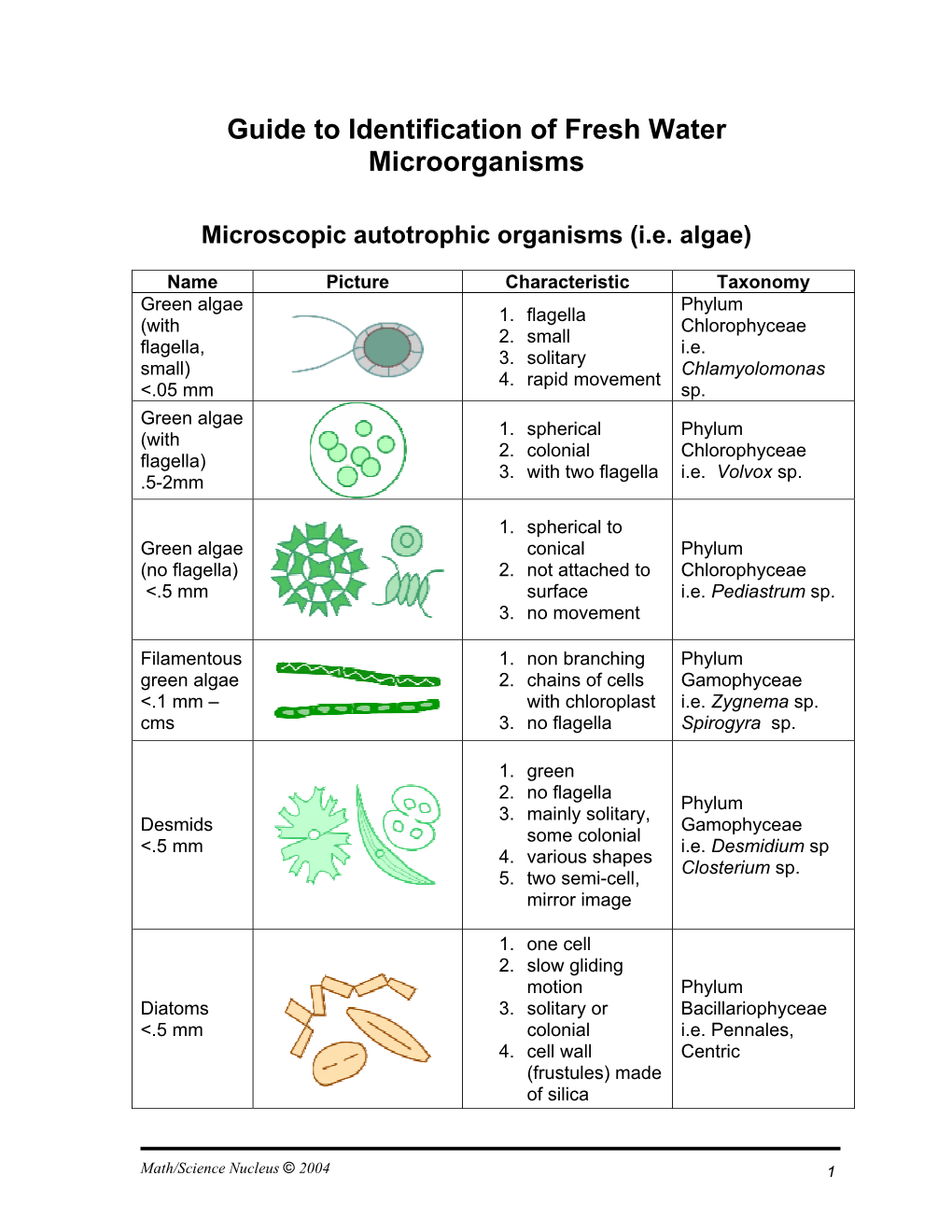

Guide to Identification of Fresh Water Microorganisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basal Body Structure and Composition in the Apicomplexans Toxoplasma and Plasmodium Maria E

Francia et al. Cilia (2016) 5:3 DOI 10.1186/s13630-016-0025-5 Cilia REVIEW Open Access Basal body structure and composition in the apicomplexans Toxoplasma and Plasmodium Maria E. Francia1* , Jean‑Francois Dubremetz2 and Naomi S. Morrissette3 Abstract The phylum Apicomplexa encompasses numerous important human and animal disease-causing parasites, includ‑ ing the Plasmodium species, and Toxoplasma gondii, causative agents of malaria and toxoplasmosis, respectively. Apicomplexans proliferate by asexual replication and can also undergo sexual recombination. Most life cycle stages of the parasite lack flagella; these structures only appear on male gametes. Although male gametes (microgametes) assemble a typical 9 2 axoneme, the structure of the templating basal body is poorly defined. Moreover, the rela‑ tionship between asexual+ stage centrioles and microgamete basal bodies remains unclear. While asexual stages of Plasmodium lack defined centriole structures, the asexual stages of Toxoplasma and closely related coccidian api‑ complexans contain centrioles that consist of nine singlet microtubules and a central tubule. There are relatively few ultra-structural images of Toxoplasma microgametes, which only develop in cat intestinal epithelium. Only a subset of these include sections through the basal body: to date, none have unambiguously captured organization of the basal body structure. Moreover, it is unclear whether this basal body is derived from pre-existing asexual stage centrioles or is synthesized de novo. Basal bodies in Plasmodium microgametes are thought to be synthesized de novo, and their assembly remains ill-defined. Apicomplexan genomes harbor genes encoding δ- and ε-tubulin homologs, potentially enabling these parasites to assemble a typical triplet basal body structure. -

Molecular Data and the Evolutionary History of Dinoflagellates by Juan Fernando Saldarriaga Echavarria Diplom, Ruprecht-Karls-Un

Molecular data and the evolutionary history of dinoflagellates by Juan Fernando Saldarriaga Echavarria Diplom, Ruprecht-Karls-Universitat Heidelberg, 1993 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Botany We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA November 2003 © Juan Fernando Saldarriaga Echavarria, 2003 ABSTRACT New sequences of ribosomal and protein genes were combined with available morphological and paleontological data to produce a phylogenetic framework for dinoflagellates. The evolutionary history of some of the major morphological features of the group was then investigated in the light of that framework. Phylogenetic trees of dinoflagellates based on the small subunit ribosomal RNA gene (SSU) are generally poorly resolved but include many well- supported clades, and while combined analyses of SSU and LSU (large subunit ribosomal RNA) improve the support for several nodes, they are still generally unsatisfactory. Protein-gene based trees lack the degree of species representation necessary for meaningful in-group phylogenetic analyses, but do provide important insights to the phylogenetic position of dinoflagellates as a whole and on the identity of their close relatives. Molecular data agree with paleontology in suggesting an early evolutionary radiation of the group, but whereas paleontological data include only taxa with fossilizable cysts, the new data examined here establish that this radiation event included all dinokaryotic lineages, including athecate forms. Plastids were lost and replaced many times in dinoflagellates, a situation entirely unique for this group. Histones could well have been lost earlier in the lineage than previously assumed. -

Eukaryotic Microorganisms Algae and Protozoans 2

Eukaryotic Microorganisms Algae and Protozoans 2 Eukaryotic Microorganisms . prominent members of ecosystems . useful as model systems and industry . some are major human pathogens . two groups . protists . fungi 3 Kingdom Protista . Algae - eukaryotic organisms, usually unicellular and colonial, that photosynthesize with chlorophyll a . Protozoa - unicellular eukaryotes that lack tissues and share similarities in cell structure, nutrition, life cycle, and biochemistry 4 Algae .Photosynthetic organisms .Microscopic forms are unicellular, colonial, filamentous .Macroscopic forms are colonial and multicellular .Contain chloroplasts with chlorophyll and other pigments .Cell wall .May or may not have flagella 5 6 Algae .Most are free-living in fresh and marine water – plankton .Provide basis of food web in most aquatic habitats .Produce large proportion of atmospheric O2 .Dinoflagellates can cause red tides and give off toxins that cause food poisoning with neurological symptoms .Classified according to types of pigments and cell wall .Used for cosmetics, food, and medical products 7 Protozoa Protozoa 9 .Diverse group of 65,000 species .Vary in shape, lack a cell wall .Most are unicellular; colonies are rare .Most are harmless, free-living in a moist habitat .Some are animal parasites and can be spread by insect vectors .All are heterotrophic – lack chloroplasts .Cytoplasm divided into ectoplasm and endoplasm .Feed by engulfing other microbes and organic matter Protozoa 10 .Most have locomotor structures – flagella, cilia, or pseudopods .Exist as trophozoite – motile feeding stage .Many can enter into a dormant resting stage when conditions are unfavorable for growth and feeding – cyst .All reproduce asexually, mitosis or multiple fission; many also reproduce sexually – conjugation Figure 5.27 11 Protozoan Identification 12 . -

![28-Protistsf20r.Ppt [Compatibility Mode]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9929/28-protistsf20r-ppt-compatibility-mode-159929.webp)

28-Protistsf20r.Ppt [Compatibility Mode]

9/3/20 Ch 28: The Protists (a.k.a. Protoctists) (meet these in more detail in your book and lab) 1 Protists invent: eukaryotic cells size complexity Remember: 1°(primary) endosymbiosis? -> mitochondrion -> chloroplast genome unicellular -> multicellular 2 1 9/3/20 For chloroplasts 2° (secondary) happened (more complicated) {3°(tertiary) happened too} 3 4 Eukaryotic “supergroups” (SG; between K and P) 4 2 9/3/20 Protists invent sex: meiosis and fertilization -> 3 Life Cycles/Histories (Fig 13.6) Spores and some protists (Humans do this one) 5 “Algae” Group PS Pigments Euglenoids chl a & b (& carotenoids) Dinoflagellates chl a & c (usually) (& carotenoids) Diatoms chl a & c (& carotenoids) Xanthophytes chl a & c (& carotenoids) Chrysophytes chl a & c (& carotenoids) Coccolithophorids chl a & c (& carotenoids) Browns chl a & c (& carotenoids) Reds chl a, phycobilins (& carotenoids) Greens chl a & b (& carotenoids) (more groups exist) 6 3 9/3/20 Name word roots (indicate nutrition) “algae” (-phyt-) protozoa (no consistent word ending) “fungal-like” (-myc-) Ecological terms plankton phytoplankton zooplankton 7 SG: Excavata/Excavates “excavated” feeding groove some have reduced mitochondria (e.g.: mitosomes, hydrogenosomes) 8 4 9/3/20 SG: Excavata O: Diplomonads: †Giardia Cl: Parabasalids: Trichonympha (bk only) †Trichomonas P: Euglenophyta/zoa C: Kinetoplastids = trypanosomes/hemoflagellates: †Trypanosoma C: Euglenids: Euglena 9 SG: “SAR” clade: Clade Alveolates cell membrane 10 5 9/3/20 SG: “SAR” clade: Clade Alveolates P: Dinoflagellata/Pyrrophyta: -

The Macronuclear Genome of Stentor Coeruleus Reveals Tiny Introns in a Giant Cell

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Biology) Department of Biology 2-20-2017 The Macronuclear Genome of Stentor coeruleus Reveals Tiny Introns in a Giant Cell Mark M. Slabodnick University of California, San Francisco J. G. Ruby University of California, San Francisco Sarah B. Reiff University of California, San Francisco Estienne C. Swart University of Bern Sager J. Gosai University of Pennsylvania See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/biology_papers Recommended Citation Slabodnick, M. M., Ruby, J. G., Reiff, S. B., Swart, E. C., Gosai, S. J., Prabakaran, S., Witkowska, E., Larue, G. E., Gregory, B. D., Nowacki, M., Derisi, J., Roy, S. W., Marshall, W. F., & Sood, P. (2017). The Macronuclear Genome of Stentor coeruleus Reveals Tiny Introns in a Giant Cell. Current Biology, 27 (4), 569-575. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.12.057 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/biology_papers/49 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Macronuclear Genome of Stentor coeruleus Reveals Tiny Introns in a Giant Cell Abstract The giant, single-celled organism Stentor coeruleus has a long history as a model system for studying pattern formation and regeneration in single cells. Stentor [1, 2] is a heterotrichous ciliate distantly related to familiar ciliate models, such as Tetrahymena or Paramecium. The primary distinguishing feature of Stentor is its incredible size: a single cell is 1 mm long. Early developmental biologists, including T.H. Morgan [3], were attracted to the system because of its regenerative abilities—if large portions of a cell are surgically removed, the remnant reorganizes into a normal-looking but smaller cell with correct proportionality [2, 3]. -

Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program, Final Reports of Principal Investigators. Volume 71

Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Final Reports of Principal Investigators Volume 71 November 1990 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service Office of Oceanography and Marine Assessment Ocean Assessments Division Alaska Office U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Minerals Management Service Alaska OCS Region OCS Study, MMS 90-0094 "Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Final Reports of Principal Investigators" ("OCSEAP Final Reports") continues the series entitled "Environmental Assessment of the Alaskan Continental Shelf Final Reports of Principal Investigators." It is suggested that reports in this volume be cited as follows: Horner, R. A. 1981. Bering Sea phytoplankton studies. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA, OCSEAP Final Rep. 71: 1-149. McGurk, M., D. Warburton, T. Parker, and M. Litke. 1990. Early life history of Pacific herring: 1989 Prince William Sound herring egg incubation experiment. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA, OCSEAP Final Rep. 71: 151-237. McGurk, M., D. Warburton, and V. Komori. 1990. Early life history of Pacific herring: 1989 Prince William Sound herring larvae survey. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA, OCSEAP Final Rep. 71: 239-347. Thorsteinson, L. K., L. E. Jarvela, and D. A. Hale. 1990. Arctic fish habitat use investi- gations: nearshore studies in the Alaskan Beaufort Sea, summer 1988. U.S. Dep. Commer., NOAA, OCSEAP Final Rep. 71: 349-485. OCSEAP Final Reports are published by the U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Ocean Service, Ocean Assessments Division, Alaska Office, Anchorage, and primarily funded by the Minerals Management Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, through interagency agreement. -

There Is Not a Latin Root Word Clear Your Desk Protist Quiz Grade Quiz

There is not a Latin Root Word Clear your desk Protist Quiz Grade Quiz Malaria Fever Wars Classification Kingdom Protista contains THREE main groups of organisms: 1. Protozoa: “animal-like protists” 2. Algae: “plant-like protists” 3. Slime & Water Molds: “fungus-like protists” Basics of Protozoa Unicellular Eukaryotic unlike bacteria 65, 000 different species Heterotrophic Free-living (move in aquatic environments) or Parasitic Habitats include oceans, rivers, ponds, soil, and other organisms. Protozoa Reproduction ALL protozoa can use asexual reproduction through binary fission or multiple fission FEW protozoa reproduce sexually through conjugation. Adaptation Special Protozoa Adaptations Eyespot: detects changes in the quantity/ quality of light, and physical/chemical changes in their environment Cyst: hardened external covering that protects protozoa in extreme environments. Basics of Algae: “Plant-like” protists. MOST unicellular; SOME multicellular. Make food by photosynthesis (“autotrophic prostists”). Were classified as plants, BUT… – Lack tissue differentiation- NO roots, stems, leaves, etc. – Reproduce differently Most algal cells have pyrenoids (organelles that make and store starch) Can use asexual or sexual reproduction. Algae Structure: Thallus: body portion; usually haploid Body Structure: 1) unicellular: single-celled; aquatic (Ex.phytoplankton, Chlamydomonas) 2) colonial: groups of coordinated cells; “division of labor” (Ex. Volvox) 3) filamentous: rod-shaped thallus; some anchor to ocean bottom (Ex. Spyrogyra) 4) multicellular: large, complex, leaflike thallus (Ex. Macrocystis- giant kelp) Basics of Fungus-like Protists: Slime Molds: Water Molds: Once classified as fungi Fungus-like; composed of Found in damp soil, branching filaments rotting logs, and other Commonly freshwater; decaying matter. some in soil; some Some white, most yellow parasites. -

Eukaryotes Microbes

rator abo y M L ic ve ro IV Eukaryote Microbes 1–7 ti b c i a o r l o e t g y n I 1 Algae, 2 Lichens, 3 Fungi, I I I I I I I I I I I B 4 Fleshy Fungi, 5 Protozoa, s a e s c ic n , A ie 6 Slime Molds, 7 Water Molds p Sc pl h ied & Healt Eukaryotes 1 Algae top of page ● Objectives/Key Words ✟ 9 motility & structure videos ● Algal Thallus ✟ Carpenter’s diatom motility ● Algal Wet Mount (Biosafety Level 1)✲✱✓ ✟ Chlamydomonas motility ● Algal Wet Mount (Biosafety Level 2)✲✱✓ ✟ Diatom gliding movement ● Algal Wet Mount (disposable loop) ✲✱✱✓ ✟ Euglena motility ● Microscopic Algae✓ ✟ Gyrosigma motility ✟ ❍ Green Algae (Chlorophyta) ✟ Noctiluca scintillans motility ✟ ❍ Chlamydomonas ✟ Peridinium dinoflagellate motility ✟ ❍ Euglenoids (Euglenophyta) ✟ Synura cells & colony ❍ Diatoms (Chrysophyta) ✟ Volvox flagellate cells ✟✟ ❍ 1 frustules & motility ◆ ❍ 2 cell division ❖14 scenic microbiology, 60 images, 9 videos ❍ 3 sexual reproduction ❖ Biofouling 1, 2 ❍ 4 striae ❖ Coral Bleaching: Hawaii ✟◆ ◆ Volvox ❍ Dinoflagellates (Pyrrophyta) ❖ Coral Reefs: Pacific Ocean ❍ Red Tide 1–2 ❖ Coral Reefs 2: Andaman Sea, Indian Ocean◆ ❖ “Doing the Laundry”, India◆◆ ● Eukaryotes Quick Quiz 1A: Algae ❖ Green Lake, Lanzarote◆ ● Eukaryotes Quick Quiz 1B: Best Practice ❖ Garden Pond, British Columbia Canada, 1◆, 2 ● Eukaryotes Question Bank1.1✓–1.16◆◆◆◆◆◆◆◆✟✟✟ ❖ Marine Luminescence, Sucia Island, WA, US◆ ❖ Red Tide, Vancouver & Comox, Canada ● 35 interactive pdf pages ❖ Sea Turtle Tracks, Galápagos Islands◆ ● 112 illustrations, 80 images of algae ❖ Sea Turtles & Sea -

Volvox Barberi Flocks, Forming Near-Optimal, Two

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/279059; this version posted March 8, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Volvox barberi flocks, forming near-optimal, two-dimensional, polydisperse lattice packings Ravi Nicholas Balasubramanian1 1Harriton High School, 600 North Ithan Avenue, Bryn Mawr, PA 19010, USA Volvox barberi is a multicellular green alga forming spherical colonies of 10000-50000 differentiated somatic and germ cells. Here, I show that these colonies actively self-organize over minutes into “flocks" that can contain more than 100 colonies moving and rotating collectively for hours. The colonies in flocks form two-dimensional, irregular, \active crystals", with lattice angles and colony diameters both following log-normal distributions. Comparison with a dynamical simulation of soft spheres with diameters matched to the Volvox samples, and a weak long-range attractive force, show that the Volvox flocks achieve optimal random close-packing. A dye tracer in the Volvox medium revealed large hydrodynamic vortices generated by colony and flock rotations, providing a likely source of the forces leading to flocking and optimal packing. INTRODUCTION behavior (see, e.g., [8, 9] and references therein) but their interactions are often dominated by viscous forces (e.g. fluid drag) unlike larger organisms which are The remarkable multicellular green alga Volvox barberi dominated by inertial forces. Here, I show that V. [1] forms spherical colonies of 10,000 to 50,000 cells barberi colonies, which are themselves composed of many embedded in a glycol-protein based extra cellular matrix individual cells acting together, show collective behavior (ECM) and connected by cytoplasmic bridges that may at a higher level of organization. -

Wrc Research Report No. 131 Effects of Feedlot Runoff

WRC RESEARCH REPORT NO. 131 EFFECTS OF FEEDLOT RUNOFF ON FREE-LIVING AQUATIC CILIATED PROTOZOA BY Kenneth S. Todd, Jr. College of Veterinary Medicine Department of Veterinary Pathology and Hygiene University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 61801 FINAL REPORT PROJECT NO. A-074-ILL This project was partially supported by the U. S. ~epartmentof the Interior in accordance with the Water Resources Research Act of 1964, P .L. 88-379, Agreement No. 14-31-0001-7030. UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS WATER RESOURCES CENTER 2535 Hydrosystems Laboratory Urbana, Illinois 61801 AUGUST 1977 ABSTRACT Water samples and free-living and sessite ciliated protozoa were col- lected at various distances above and below a stream that received runoff from a feedlot. No correlation was found between the species of protozoa recovered, water chemistry, location in the stream, or time of collection. Kenneth S. Todd, Jr'. EFFECTS OF FEEDLOT RUNOFF ON FREE-LIVING AQUATIC CILIATED PROTOZOA Final Report Project A-074-ILL, Office of Water Resources Research, Department of the Interior, August 1977, Washington, D.C., 13 p. KEYWORDS--*ciliated protozoa/feed lots runoff/*water pollution/water chemistry/Illinois/surface water INTRODUCTION The current trend for feeding livestock in the United States is toward large confinement types of operation. Most of these large commercial feedlots have some means of manure disposal and programs to prevent runoff from feed- lots from reaching streams. However, there are still large numbers of smaller feedlots, many of which do not have adequate facilities for disposal of manure or preventing runoff from reaching waterways. The production of wastes by domestic animals was often not considered in the past, but management of wastes is currently one of the largest problems facing the livestock industry. -

An Evolutionary Switch in the Specificity of an Endosomal CORVET Tether Underlies

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/210328; this version posted October 27, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Title: An evolutionary switch in the specificity of an endosomal CORVET tether underlies formation of regulated secretory vesicles in the ciliate Tetrahymena thermophila Daniela Sparvolia, Elisabeth Richardsonb*, Hiroko Osakadac*, Xun Land,e*, Masaaki Iwamotoc, Grant R. Bowmana,f, Cassandra Kontura,g, William A. Bourlandh, Denis H. Lynni,j, Jonathan K. Pritchardd,e,k, Tokuko Haraguchic,l, Joel B. Dacksb, and Aaron P. Turkewitza th a Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, The University of Chicago, 920 E 58 Street, Chicago IL USA b Department of Cell Biology, University of Alberta, Canada c Advanced ICT Research Institute, National Institute of Information and Communications Technology (NICT), Kobe 651-2492, Japan. d Department of Genetics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, 94305 e Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305 f current affiliation: Department of Molecular Biology, University of Wyoming, Laramie g current affiliation: Department of Genetics, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06510 h Department of Biological Sciences, Boise State University, Boise ID 83725-1515 I Department of Integrative Biology, University of Guelph, Guelph ON N1G 2W1, Canada j current affiliation: Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, V6T 1Z4, Canada k Department of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, 94305 l Graduate School of Frontier Biosciences, Osaka University, Suita 565-0871, Japan. -

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016

Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve Management Plan 2011-2016 April 1981 Revised, May 1982 2nd revision, April 1983 3rd revision, December 1999 4th revision, May 2011 Prepared for U.S. Department of Commerce Ohio Department of Natural Resources National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Division of Wildlife Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management 2045 Morse Road, Bldg. G Estuarine Reserves Division Columbus, Ohio 1305 East West Highway 43229-6693 Silver Spring, MD 20910 This management plan has been developed in accordance with NOAA regulations, including all provisions for public involvement. It is consistent with the congressional intent of Section 315 of the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended, and the provisions of the Ohio Coastal Management Program. OWC NERR Management Plan, 2011 - 2016 Acknowledgements This management plan was prepared by the staff and Advisory Council of the Old Woman Creek National Estuarine Research Reserve (OWC NERR), in collaboration with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources-Division of Wildlife. Participants in the planning process included: Manager, Frank Lopez; Research Coordinator, Dr. David Klarer; Coastal Training Program Coordinator, Heather Elmer; Education Coordinator, Ann Keefe; Education Specialist Phoebe Van Zoest; and Office Assistant, Gloria Pasterak. Other Reserve staff including Dick Boyer and Marje Bernhardt contributed their expertise to numerous planning meetings. The Reserve is grateful for the input and recommendations provided by members of the Old Woman Creek NERR Advisory Council. The Reserve is appreciative of the review, guidance, and council of Division of Wildlife Executive Administrator Dave Scott and the mapping expertise of Keith Lott and the late Steve Barry.