Taryn O´Leary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hokuo Online Trade Mission

HOKUO ONLINE TRADE MISSION February 12 - 17, 2021 Nordic Delegates 02 ARCTIC RIGHTS MANAGEMENT ØYVIND STRØNEN A&R ASIA HEAD OF LABEL SERVICE NICLAS LUNDIN CO-FOUNDER / SONGWRITER / PRODUCER [email protected] PROFESSIONAL INSTRUCTOR AND TEACHER +47 40218414 WWW.ARCTICRIGHTS.COM [email protected] +46706622960 Arctic Rights Management is the biggest indie publisher in ARTOVIK.SE Norway, where we have about 50 writers in the roster, ranging from jazz, to heavy metal. In the field of J-pop and K-pop we Niclas Lundin is a Multi Platinum Songwriter with songs released all have a few that are aiming to be producers and songwriters, over the world by artists including Martin Garrix, Rick Springfield, where I am in charge of this particular part of our business. My Namie Amuro, SHINee, James LaBrie, Koda Kumi, Kiz-My-FtII, background is from being a touring musician in rock bands, Dada Life, Cho Yong Pil and many more. before I got a degree in musicology and took a role in Arctic Niclas often lectures about songwriting both in Sweden and abroad Rights spring 2019. I've always been in love with Japanese and he is well known for hosting professional songwriting camps and culture, and I’ve visited many times. I also spent a year trying to he is part of staff at the three songwriting Academies of Sweden; learn how to speak Japanese, but I’m afraid my vocabulary is Musikmakarna, Dreamhill Music Academy and Songwriting for an limited to ordering ok onomiyaki and beer. International Market. Arctic Rights also has a label as well where we release new music every month (mainly from own writers), and would be very I'm hoping to grow my network of professional contacts both for interested to connect our artist projects to the Japanese scene or myself as a music professional as well as professional camp host, sync opportunities. -

Artist Branding in the Danish Music Industry

ARTIST BRANDING IN THE DANISH MUSIC INDUSTRY A study of Universal Music Denmark and its artists on creating and sustaining brand identity in the technological disrupted market of the Danish music industry Supervisor: Toyoko Sato Assignment: Master thesis Study Program: International Business Communication; Intercultural Marketing Hand in date: 17th of September 2018 Number of pages: 69 Number of characters: 157.422 Name: Ulrik Svinding Student number: 46593 Resume National music industries and markets all over the world have been affected by the technological disruption. In the Danish market, the Danish label Universal Music Denmark have had to make considerable changes to adjust to the new conditions of the market. Changes in the dynamics of media have challenged the company and its artists their branding strategies. With the implementation of new strategies and labels and artists now use social media as an essential part of their promotional strategies. It has meant a restructuring of Universal Music Denmark which now relies on data-gathering techniques to form the commutative strategies of their artistic brands. On the artistic level, these are forces to formulate and create strong brands as the role of the record label has changed. Image, identity, and self-understanding are but a few of the necessary considerations that artistic brands have to consider to stay unique and relevant within the Danish music industry and media landscape. This thesis investigates how two artistic brands experience, reflect and strategized the development of their brand. Furthermore, it studies the role of the new Universal Music Denmark its practices and role in helping its artists. -

DISCOGRAPHY MICHAEL ILBERT Producer,Mixer, Engineer

Zippelhaus 5a 20457 Hamburg Tel: 040 / 28 00 879 - 0 Fax: 040 / 28 00 879 - 28 DISCOGRAPHY mail: [email protected] MICHAEL ILBERT producer,mixer, engineer P3 Guld Award 2015 "Best Pop": Beatrice Eli Danish Music Awards 2014 "Best Popalbum of the year": Michael Falch "Sommeren Kom Ny Tilbage" Spellemann's Awards 2014 "Best Newcomer" & "Best Popsolist": Monica Heldal "Boy From The North" (Norwegian Grammy) EMAs 2014 "Best German Act": Revolverheld "Immer In Bewegung" Grammy Nomination "Rock of the year": Side Effects "A Walk In The Space Between Us" Sweden 2014 Grammy Nomination 2013 "Best record of the year": Taylor Swift "We are never ever getting back together" Grammy Nomination "Rock of the year": The Hives "Lex Hives" Sweden 2013 Taylor Swift "Shake it off" (4x USA) Taylor Swift "Red"(3x USA) Bosse "Kraniche" Revolverheld "Ich Lass Für Dich Das Licht An" Herbert Grönemeyer "Schiffsverkehr" / "Zeit dass sich was dreht" Jupiter Jones "Still" Platin Award Laleh "Sjung"(SWE) Pink "Funhouse" (GER, SWE) Robyn "Robyn" (SWE) Cardigans "Long before daylight" (SWE) Roxette "Centre of my heart" (SWE) / "Have a nice day" (SWE) Ulf Lundell "I ett vinterland" (SWE) Lars Winnerbäck "Kom" (SWE) Laleh "Colors" (SWE) Herbert Grönemeyer "Dauernd Jetzt" (GER) Revolverheld "Immer In Bewegung" (GER, AUT) Ulf Lundell "Trunk" (SWE) Katy Perry "Roar" Amanda Jensen "Hyms for the haunted" (SWE) Thåström "Beväpna dig med vingar" (SWE) Jupiter Jones "Jupiter Jones"/ "Still"(AU) Gold Award Avril Lavigne "What the hell" (SWE) Pink "Raise your glass" Selig -

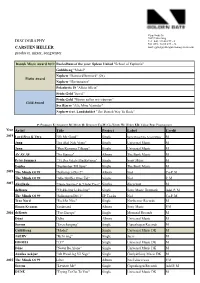

DISCOGRAPHY CARSTEN HELLER Producer, Mixer, Songwriter

Zippelhaus 5a 20457 Hamburg DISCOGRAPHY Tel: 040 / 28 00 879 - 0 Fax: 040 / 28 00 879 - 28 CARSTEN HELLER mail: [email protected] producer, mixer, songwriter Danish Music Award 2012 Rockalbum of the year: Spleen United "School of Euphoria" Gulddreng "Model" Nephew "DanmarkDenmark" (2x) Platin Award Nephew "Hjertestarter" Polarkreis 18 "Allein Allein" Frida Gold "Juwel" Frida Gold "Wovon sollen wir träumen" Gold Award Sys Bjerre "Alle Mine Veninder" Nephew feat. Landsholdet "The Danish Way To Rock" P: Producer E: Engineer M: Mixer R: Remixer Co-W: Co-Writer W: Writer ED: Editor Pro: Programmer Year Artist Title Project Label Credit 2019 Lord Siva & Vera "Oh My Good" Single Sony Music/One Seven Music M Jung "Jeg Skal Nok Vente" Single Universal Music M Jung "Hun Kommer Tilbage" Single Universal Music M AV AV AV "No Statues" Album The Bank Music M Peter Sommer "Vi Der Valgte Mælkevejen" Single Sony Music M Dopha "September Till June" Single The Bank Music M 2018 The Minds Of 99 "Solkongen Del 2" Album No3 Co-P, M The Minds Of 99 "Alle Skuffer Over Tid" Single No3 P, M 2017 Aksglæde "Næste Sommer" & "Under Press" Singles disco:wax M deRoute "Ulykkeling Lykkeling" Single Sony Music Denmark Add. P, M The Minds Of 99 "Solkongen Del 1" EP Tracks No3 Co-P, M True Nord "Feel So Nice" Single Northerner Records M Simon Kvamm Vandmand Album Sony Music P,M 2016 deRoute "Fort Europa" Single Mermaid Records M Dúné Delta Album Universal Music M Saveus "Everchanging" Single Copenhagen Records M Gulddreng "Model" Single Universal Music DK M JAERV -

Tal, Tendenser, Markedsstatistik Og Analyser + Artikler Om Den Danske

STATUS 2008/09: UAFHÆNGIGE SELSKABER 04 MODSÆTNINGERNES ÅR 20 UNDER DIGITALT PRES IFPI’s formand, Henrik Daldorph, ser Væksten i det digitale marked presser Tal, tendenser, markedsstatistik og tilbage på markante begivenheder for den uafhængige sektor, som i 2008 havde analyser + artikler om den danske pladebranchen i 2008 og første halvdel af tilbagegang. Vi analyserer udviklingen. pladebranche 2008/09 2009. Fra den nye oplevelseszone til dom- men i The Pirate Bay-sagen. FREELANCERE I 30 MUSIKBRANCHEN KUNSTNERNE HAR STADIG Pladebranchen omfatter hundredvis af 14 BRUG FOR ET PLADESELSKAB arbejdspladser. De senere års omfattende Interview med en af pladebranchens suc- forandringer har skabt helt nye struktu- cesfulde ledere Jakob Sørensen, direktør rer – og en lang række nye virksomheder, for Copenhagen Records. Om hvad kunst- der fungerer som underleverandører til nere skal bruge et pladeselskab til i 2009. den etablerede del af branchen. Vi ser Om manglende skarphed i branchen. Og nærmere på freelancemarkedet. om forventningerne til fremtiden. Og så får vi historien om Alphabeats internationale succes. Plus: Hitlisterne 2008 / Guld- & platincertificeringer 2008 / DMA09 og meget mere Foto: Kristian Holm PLADEBRANCHEN.08 Velkommen til Pladebranchen.08 f Vi har forud for udarbejdelsen af IFPI’s femte årsskrift I et længere interview fortæller Jakob Sørensen fra Copen- overvejet grundigt, om vi skulle kalde det noget andet end hagen Records således bl.a. om selskabets arbejde med ”Pladebranchen.08”, fordi vores medlemmer, der pt. står for en af de største, danske succeshistorier i nyere tid – Alpha- ca. 95 % af omsætningen af indspillet musik i Danmark, i beat – og om hvorfor kunstnere stadig kan have glæde stadigt højere grad beskæftiger sig med alt muligt andet end af et pladeselskab i 2009. -

Musikselskaber 2012 – Tal Og Perspektiver?

MUSIK- SELSKABER 2012 tal og perspektiver Musikselskaber 2012 - tal og perspektiver s. 2 FOTO: sophie bech FORORD Det danske musikmarked er i rivende ud- Det betyder ikke, at alle udfordringer er for- vikling. Det viser tallene for 2012 tydeligere svundet som dug for solen, og at vi nu skal end et stjerneskud på en mørk nattehim- læne os selvtilfredse tilbage i stolen. Vi har mel. For første gang nogensinde er den digi- stadig en vigtig opgave med at skabe trans- tale omsætning for salg af indspillet musik parens, så de massive mængder data, digi- større end den fysiske. Og selvom vi også i taliseringen fører med sig, giver mening for 2012 oplevede et mindre fald i den samlede verden omkring os. Og så skal vi fortsætte omsætning, er det med blot 3 % tale om den med den progressive forbrugerorienterede mindste nedgang siden årtusindeskiftet. tilgang til det digitale marked, der er på vej til at bringe os ud af tusmørket og ind i en Hvad der imidlertid er endnu mere inte- ny spændende virkelighed. ressant, er de digitale vækstkurver, vi har set i det forgangne år. Indtægterne fra Vi er der ikke helt endnu, men målet er streamingtjenester som Spotify, WiMP og klart. Vi vil være med til at forme en bære- Play er næsten fordoblet i 2012, og de udgør dygtig fremtid hvor det, at vi forbruger og allerede nu en fjerdedel af musikselskaber- deler musik med hinanden, er positivt for nes samlede omsætning. Og vi er først lige både danske musikelskere, danske musik- begyndt. Samtidig fortsætter danskerne selskaber og danske musikere. -

Entertainment on Board

September 2007 Entertainment on board Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End Airbus A340 Handset Business Class Cursor Navigation Arrows Press to enter your selection Video Screen On/Off On-Screen Menu Channel Select Volume Control Reading Light Attendant Call Call Reset Game Controls Instructions will be given when playing the game. Menu Bar X 1 Quit Light Language Pause Forward Sound Reverse Play Airbus A340 Handset Economy Extra and Economy Class Cursor Navigation Arrows Channel Select Volume Control Attendant Call Call Reset Reading Light Video Screen On/Off On-Screen Menu Game Controls Press to enter your selection Menu Bar Quit Light Language Sound To play, place the handset in a horizontal position and use both hands to control the action. To replace the handset in the armrest, pull the cable gently to release the cable lock. Welcome aboard For your enjoyment on board this aircraft, SAS has provided first-class entertainment. Using touch-screen technology, choose your own entertainment directly on your personal video screen. Alternatively, you can use your personal handset to navigate around the screen and make your choices. We have provided a variety of movies, audio programs and games, as well as information on the progress of your flight. Before take-off, the forward-looking camera and the moving map are available on all seatback-mounted video screens. Just reach out and touch the screen to activate it. Once airborne, armrest-mounted screens may be used. The downward-looking camera will now be activated and the moving map channel will continually be updated to let you know where you are, how far it is to your destination, and to display other relevant flight information as well as video information programs relating to your flight. -

Downloadmarkedet Er I Vækst

MUSIK- SELSKABER 2011 tal og perspektiver Musikselskaber 2011 - tal og perspektiver s. 2 FOTO: sophie bech FORORD Der er løbet meget vand i den digitale å si- også downloadmarkedet er i vækst. Som den Musikselskaber 2010 blev udgivet for vi har set det i andre lande tyder det ikke snart et år siden. Nye musiktjenester som på, at streaming kannibaliserer download- Spotify, Deezer, Rara og Music Unlimited indtægterne. Tværtimod fortsætter down- har slået portene op for danske musikfor- loadindtægterne med at stige – alene i 2011 brugere, og selvom det endnu er for tidligt at oplevede det digitale albumsalg i Danmark se markante økonomiske ændringer i mar- en imponerende vækst på 29 %. kedet, skal man være pessimistisk anlagt for ikke at tro på nogle spændende og frugtbare Nettet skaber fantastiske muligheder for år forude. Og vi har brug for en positiv ud- os alle sammen. Desværre også for skrup- vikling, hvis vi fortsat skal kunne investere pelløse bagmænd og kyniske spekulanter, i et musikmiljø, hvor talentfulde musikere, der hverken bekymrer sig om forbrugerne, producere og lydteknikere kan folde vinger- kulturen eller sammenhængskraften i vores ne ud og berige vores kultur. samfund. Derfor er det stadig helt afgøren- de, at man fra politisk side insisterer på, at Myten om, at musikbranchens professio- nettet ikke skal være et lovløst tilholdssted, nelle niveauer bliver overflødige i takt med hvor uærlig virksomhed sætter dagsordenen den stigende digitalisering af samfundet, på bekostning af kreativiteten, anstændig- er nemlig efterhånden så slidt, at man kan heden og en økonomisk vækst, der kommer se lige igennem den. Og tallene taler for sig os alle til gode. -

TRACK HISTORY for Jade

TRACK HISTORY for Jade Ell title artist country add info “Feliz Cumpleanos” Rebeldes Mexico song on the album “Happy Worstday” (Emi Music Int.) “Nuestro Amor” and “Rebels” (original title) a total of 5 million albums # 1 on the Mexican album charts # 1 on Billboard Top Latin Albums # 1 on Billboard Latin Albums Pop # 1 on the Brazilian abum charts (Portugese version:“Nosso Amor”) 9 nominations at the Billlboard Latin Awards 2005! (300.00 units sold in US alone) grammy for best Latin Pop Album 2006 grammy for best new artist 2006 grammy for people’s choice 2006 live version on the album “Live In Hollywood”: # 1 in Brazil # 6 on Billboard Top Latin Albums “Ai-shee-baa” Yuki Japan 400 000 units sold (English title: (Epic Music) # 1 on Japanese album charts “I’m Your Cure”) “Behind Those Words” Sandra Germany on the album Back To Life 2009 (EMI/Virgin Music) no 26 peak position on the German album charts also released in Czech and Switzerland “Mystery To Me” Sanne Salomonsen Denmark 50.000 units sold (Copenhagen records) + 7.000 (Sweden) # 1 on Danish album charts “Pleasure” Margaret Berger Norway 18.000 units sold (BMG, Norway) 2nd in the Norwegian Pop Idol “I’m Confused” Pandora Sweden # 6 on Swedish single charts (Mariann) album also released in Japan “Ilusión” Edurne Spain on the album “ILUSION” 2007 (Epic Records) peak postion no 13 on the Spanish album charts “Like Believers Do” Jonna K Finland # 4 in the Finnish Eurovision 2004 (Edel Records) member of Nylon Beat # 8 on the Finnish single charts “Responde” Diego Gonzalez Mexico also releaesed in US, Brazil and “orig.title; “The Silence” (EMI International) Chile first single with TV soap opera star (Rebeldes) incl.video. -

Hokuo Music Trade Day

7.—10.11. 2017 HOKUO MUSIC FEST 2016 HOKUO MUSIC FEST 2016 LOUD & METAL MANIA BY HOKUO MUSIC TEMPLE BALLS FINLAND Fri Nov 10th Shibuya Duo Music Exchange Loud & Metal Mania by Hokuo Music ADDRESS 〒 DOORS OPEN AT 2-14-8 O-EAST 2 3 CONTACT 17:00 ESA HARJU | [email protected] building 1F TEMPLEBALLSROCKS.COM | FACEBOOK.COM/TEMPLEBALLSROCKS Shibuya-ku Dougenzaka, Tokyo Temple Balls is an energetic 5-piece more than able to handle big stages hard rock band from Oulu (Finland). as well. Whether it be a big festival or It was founded in 2009 and put to its your local club’s stage, the band will final line-up in 2014. set your friggin’pants on fire. LINEUP (NOR) In the time-tested tradition of every- The first official single ’Hell And BEATEN TO DEATH one from Aerosmith to Van Halen, it is Feelin’Fine’ was released on Septem- the driving, hard hitting drum beats, ber 1st 2016. The debut album was (FIN) the massive wall of bass, incandes- recorded at Karma Sound Studios TEMPLE BALLS cently blazing fretboard wizardry (Thailand) in May 2016, and saw the and the melodic guitar licks that lay daylight in February 24th 2017. ’Trad- (SWE) the foundation for the band’s brazen ed Dreams’ was released via Finnish ELEINE classic rock sound, and the things record label Ranka Kustannus whose (DEN) which truly set the youngsters apart captain is the founder of Spinefarm DEFECTO from their peers is their sovereignty in Records – the label behind such acts things that really matter: memorable like Nightwish, Children of Bodom etc. -

Har Du Rettelser, Kommentarer Eller Forslag, Så Skriv Til Os På Info

Pladeselskaber Kontakt Kontaktmail Adresse Postnummer/by Hjemmeside Telefon Note A:Larm Anders Lassen/MD & Mads [email protected] , Enghavevej 40, 4. 1674 København V www.alarmmusic.dk 99340700 Primært distributør for en lang Rosted/Product, PR [email protected] række større danske artister, bl.a. Tina Dickow & Mew. En del af MBO ArtPeople Nicolaj Bundesen [email protected] Vester Farimagsgade 41 1606 København V www.artpeople.dk 72215237 Udgiver bl.a. Rasmus Seebach og Xander Auditorium Nikolaj Nørlund [email protected] www.auditorium.nu Black Pelican Media & Jacob Deichmann/MD A&R [email protected] Købmagergade 19, 4. sal 1150 København K http://www.blackpelican.dk/ 70259525 Dansk selskab med fokus på Entertainment Group licens og egen-produktion - bla. Anne Dorte Michelsen. Kører også management og publishing. Border Breakers Michael Guldhammer [email protected] Gothersgade 35, 3 1123 København K www.borderbreakers.com 70 200 238 Udgiver Infernal, Anna David, Maria Montell og Danseorkestret. COPE Records Peter Kehl [email protected] Vesterbrogade 95H 1620 København V http://www.coperecords.com/ 70201137 Blues, rock og world. Sublabel Calibrated fokusrer på jazz. Distrib. Via. VME Copenhagen Records Christian Backman/A&R, [email protected] Enghavevej 40, 4. 1674 København V http://cphrec.dk/ 35209090 DK's største uafhængige Jakob Sørensen/MD selskaber med alt fra Medina over Nephew til Spleen United. En del af MBO Cosmos Music Group Cai Leitner/MD [email protected] Grønnegade 3, 1. 1107 København K http://www.cosmosmusicgroup.co 33427700 En del af det nordiske "indie"- m/ selskab, COSMOS - tidl. Bonnier Music. Primært licenser fra udlandet. -

Musikselskaber 2010 - Tal Og Perspektiver S

Musikselskaber 2010 - tal og perspektiver s. 1 MUSIK- SELSKABER 2010 tal og perspektiver Musikselskaber 2010 - tal og perspektiver s. 2 FOTO: sophie bech “Her indsættes et citat fra teksten. Her indsættes et citat fra teksten.” Henrik Daldorph, Formand iFPI Danmark FORORD Heller ikke 2010 blev året, hvor vi fik knæk- I de skandinaviske nabolande kunne vi iagt- ket musikselskabernes negative kurve. Den tage, hvordan nye on demand-streaming- samlede omsætning er stadig nedadgående. tjenester stimulerer musikforbruget og Det går selvfølgelig ikke henover hovederne skaber grobund for nye spændende forret- på os, der arbejder professionelt med musik- ningsmodeller, der i øvrigt minimerer den ken. Alle mærker vi udfordringerne i daglig- ulovlige kopiering på internettet. I Sverige dagen. Uanset om vi er medarbejdere på et udgjorde streamingindtægterne i 2010 musikselskab eller talentfulde musikere, der mere end 65 % af den samlede digitale om- kæmper for at stable en sammenhængende sætning og står i dag for mere end 20 % af karriere på benene. musikselskabernes samlede indtjening. Det er forbilledligt og inspirerende. De kommende år vil uden tvivl også blive udfordrende, men samtidig rejser nye mu- Heldigvis tyder intet på, at vi har set mere ligheder sig i den digitale horisont. Og det end blot begyndelsen af en ny digital vir- skaber grundlag for masser af optimisme og kelighed. En virkelighed hvor alle forbru- håb. Det viste 2010 os nemlig også. gere nemt og bekvemt kan få adgang til en Musikselskaber 2010 - tal og perspektiver s. 3 ”Vi skal som branche gøre vores ypperste for, at forbrugerne får nye digitale muligheder.” mangfoldig verden af musik, uanset hvor Vi skal som branche gøre vores ypperste for, de befinder sig.