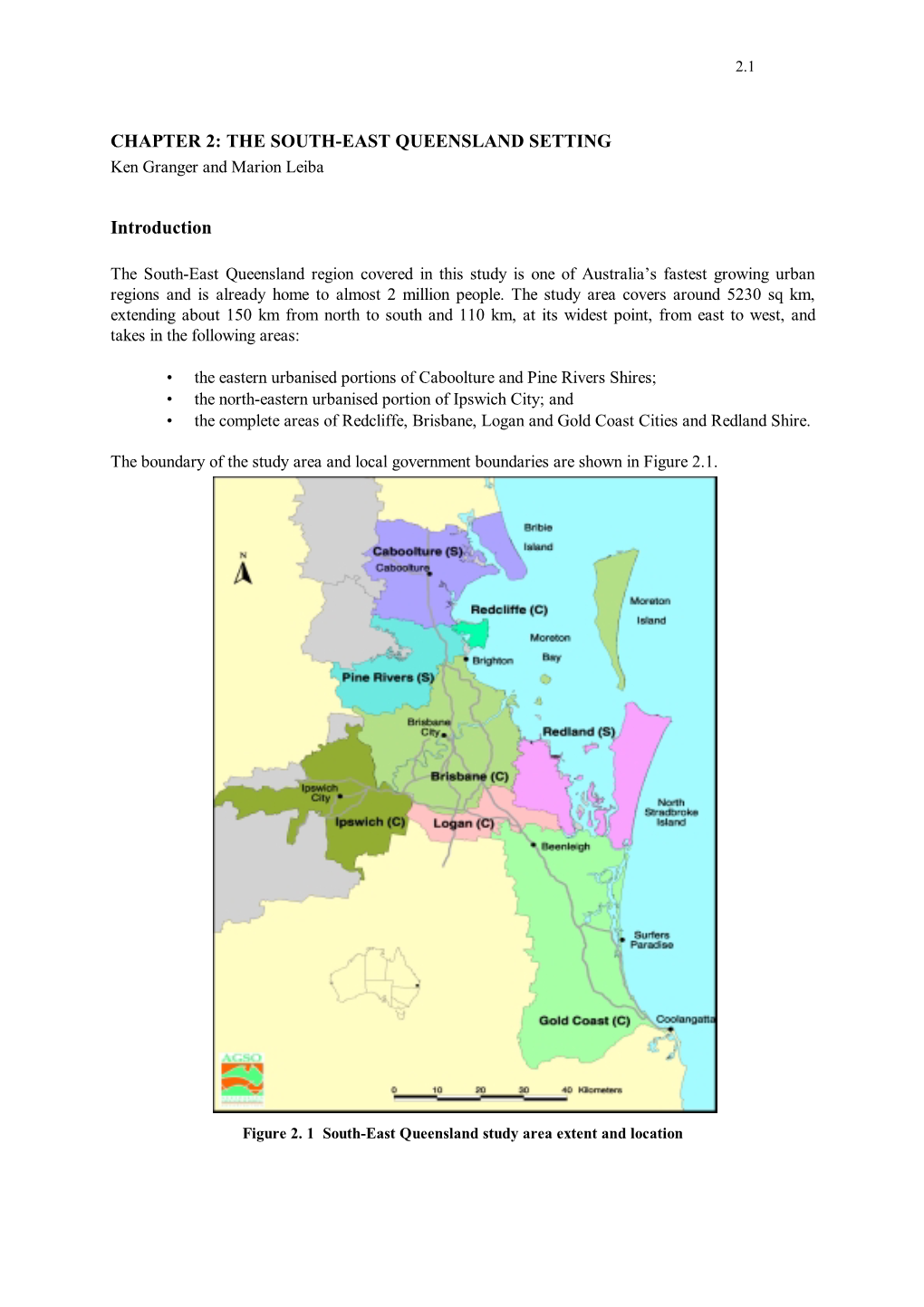

CHAPTER 2: the SOUTH-EAST QUEENSLAND SETTING Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bat Calls of New South Wales

Bat calls of New South Wales Region based guide to the echolocation calls of microchiropteran bats Michael Pennay1 , Brad Law2 & Linda Reinhold3 1 New South Wales Department of Environment and Conservation 2 State Forests of New South Wales 3 Queensland Department of Natural Resources and Mines Bat calls of New South Wales Bat calls of New South Wales Published by the NSW Department of Environment and Conservation May 2004 Copyright © NSW Department of Environment and Conservation ISBN 0 7313 6786 3 This guide is the result of a co-operative project between NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, now the NSW Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) and State Forests of NSW (SFNSW). DEC provided project funding, management, staff, reference calls, preparation and printing. SFNSW provided part funding and granted support of staff time and expertise, reference calls and editing. Research was conducted under NPWS scientific licence number A2753 and SFNSW special purpose permit for research number 05466. Material presented in this publication may be copied for personal use or republished for non-commercial purposes provided that NSW Department of Environment and Conservation is fully acknowledged as the copyright owner. Apart from these purposes or for private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process without written permission from NSW Department of Environment and Conservation. Inquiries should be addressed to the NSW Department of Environment and Conservation. This publication should be cited as follows: Pennay, M., Law, B., Reinhold, L. (2004). Bat calls of New South Wales: Region based guide to the echolocation calls of Microchiropteran bats. -

Climate Change in the South East Queensland Region

Photo: Tourism Queensland Tourism Photo: Climate change in the South East Queensland Region Rainfall Data Temperature Data Tewantin Post Office This regional summary describes Sunshine Coast the projected climate change Regional Council for the South East Queensland (SEQ) region. Somerset Regional Council Moreton Bay Regional Council Projected average temperature, Brisbane rainfall and evaporation for Brisbane City Redland Lockyer UQ Gatton Council City 2030, 2050 and 2070 under low, Valley Council Regional Amberley Council Ipswich City Council Logan medium and high greenhouse City Harrisville Council Post Office Gold gas emissions scenarios are Coast Scenic Rim City compared with historical Regional Council Council climate records. New South Wales SEQ_Map A regional profile Climate and Photo: Tourism Queensland landscape South East Queensland Key findings is home to the state’s capital, Brisbane, which has a sub-tropical Temperature climate. Rainfall in the region • Average annual temperature in SEQ has increased 0.4 °C is influenced both by tropical over the last decade (from 19.4 °C to 19.8 °C). systems from the north and fluctuations in the high pressure • Projections indicate an increase of up to 4 °C by 2070; leading ridge to the south. to annual temperatures well beyond those experienced over the last 50 years. South East Queensland is • By 2070, Amberley may have more than three times the number Australia’s fastest growing region. of days over 35 °C (increasing from an average of 12 per year The population of SEQ is heavily to 41 per year), Brisbane may have six times the number of urbanised and is generally hot days (increasing from an average of one per year to an average concentrated along the coast of six per year) and Tewantin may have nearly four times the between Noosa and Coolangatta. -

Building Nature's Safety Net 2008

Building Nature’s Safety Net 2008 Progress on the Directions for the National Reserve System Paul Sattler and Martin Taylor Telstra is a proud partner of the WWF Building Nature's Map sources and caveats Safety Net initiative. The Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia © WWF-Australia. All rights protected (IBRA) version 6.1 (2004) and the CAPAD (2006) were ISBN: 1 921031 271 developed through cooperative efforts of the Australian Authors: Paul Sattler and Martin Taylor Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage WWF-Australia and the Arts and State/Territory land management agencies. Head Office Custodianship rests with these agencies. GPO Box 528 Maps are copyright © the Australian Government Department Sydney NSW 2001 of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts 2008 or © Tel: +612 9281 5515 Fax: +612 9281 1060 WWF-Australia as indicated. www.wwf.org.au About the Authors First published March 2008 by WWF-Australia. Any reproduction in full or part of this publication must Paul Sattler OAM mention the title and credit the above mentioned publisher Paul has a lifetime experience working professionally in as the copyright owner. The report is may also be nature conservation. In the early 1990’s, whilst with the downloaded as a pdf file from the WWF-Australia website. Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, Paul was the principal This report should be cited as: architect in doubling Queensland’s National Park estate. This included the implementation of representative park networks Sattler, P.S. and Taylor, M.F.J. 2008. Building Nature’s for bioregions across the State. Paul initiated and guided the Safety Net 2008. -

Koala Conservation Status in New South Wales Biolink Koala Conservation Review

koala conservation status in new south wales Biolink koala conservation review Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... 3 2. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 6 3. DESCRIPTION OF THE NSW POPULATION .............................................................. 6 Current distribution ............................................................................................................... 6 Size of NSW koala population .............................................................................................. 8 4. INFORMING CHANGES TO POPULATION ESTIMATES ....................................... 12 Bionet Records and Published Reports ............................................................................... 15 Methods – Bionet records ............................................................................................... 15 Methods – available reports ............................................................................................ 15 Results ............................................................................................................................ 16 The 2019 Fires .................................................................................................................... 22 Methods ......................................................................................................................... -

Aboriginal Men of High Degree Studiesin Sodetyand Culture

])U Md�r I W H1// <43 H1�hi Jew Jn• Terrace c; T LUCIA. .Id 4007 �MY.Ers- Drysdale R. 0-v Cape 1 <0 �11 King Edward R Eylandt J (P le { York Prin N.Kimb �0 cess Ch arlotte Bay JJ J J Peninsula Kalumbur,:u -{.__ Wal.cott • C ooktown Inlet 1r Dampier's Lan by Broome S.W.Kimberley E. Kimberley Hooker Ck. La Grange Great Sandy Desert NORTHERN TERRITORY Port Hedland • Yuendumu , Papanya 0ga Boulia ,r>- Haasts Bluff • ,_e':lo . Alice Springs IY, Woorabin Gibson Oesert Hermannsburg• da, �igalong pe ter I QU tn"' "'= EENSLAND 1v1"' nn ''� • Ayre's Rock nn " "' r ---- ----------------------------L- T omk i nson Ra. Musgrave Ra. Everard Ra Warburton Ra. WESTERN AUSTRALIA Fraser Is. Oodnadatta · Laverton SOUTH AUSTRALIA Victoria Desert New Norcia !) Perth N EW SOUT H WALES Great Australian Bight Port �ackson �f.jer l. W. llill (lr14), t:D, 1.\ Censultlf . nt 1\n·hlk.. l �st Tl·l: ( 117} .171-'l.lS Aboriginal Men of High Degree Studiesin Sodetyand Culture General Editors: Jeremy Beckett and Grant Harman Previous titles in series From Past4 to Pt�vlova: A Comp��rlltivt Study ofIlllli1111 Smlm m Sydney & Griffith by Rina Huber Aboriginal Men of High Degree SECOND EDITION A. P. Elkin THEUNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLANDLffiRARY SOCIALSCIENCES AND HUMANITIES LIBRARY University of Queensland Press First edition 1945 Second edition © University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland, 1977 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no p�rt may be reproduced by any process without written permission. -

Table of Contents

Biolink koala conservation review Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................... 3 2. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 6 3. DESCRIPTION OF THE NSW POPULATION .............................................................. 6 Current distribution ................................................................................................... 6 Size of NSW koala population .................................................................................... 8 4. INFORMING CHANGES TO POPULATION ESTIMATES .......................................... 12 Bionet Records and Published Reports .................................................................... 15 Methods – Bionet records ................................................................................... 15 Methods – available reports ................................................................................ 15 Results .................................................................................................................. 16 The 2019 Fires .......................................................................................................... 22 Methods ............................................................................................................... 22 Results .................................................................................................................. 23 Data Deficient -

South-West Australia

REGIONAL INDIGENOUS LAND STRATEGY (rils) South-WEST AUSTRALIA Message from the ILC Chairperson Welcome to the Regional Indigenous Land Strategy (RILS) for the South-West Australia region—the first time the ILC has, through the RILS, recognised the particular environmental, social and economic features of this vast region. This RILS represents an additional, more focused layer to the ILC Group’s strategic direction as laid out in the National Indigenous Land Strategy (NILS) for the period 2018 to 2022. These are the first national and regional land strategies that I and the current ILC Board have had the honour of presenting to you, our stakeholders and partners in growing the Indigenous Estate. As you will see throughout the strategies, the ILC is focused on becoming a trusted partner in developing the Indigenous Estate to achieve economic, environmental, social and cultural benefits for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The ILC Board, staff and subsidiary companies are determined to apply the resources available to us to help transform Indigenous-held land and waters and our unique cultural assets into a source of prosperity for this and future generations. Central to our strategies has been identifying the best ways to invest and partner with you, to make our collective resources go further. On behalf of the ILC Board, I thank those who participated in consultation sessions on these important documents. Your views have informed our way forward. Please take the time to read through this regional strategy and the national strategy it THE IndIgenOUS ESTATE accompanies. Also check the ILC website and follow us on social media. -

Land Zones of Queensland

P.R. Wilson and P.M. Taylor§, Queensland Herbarium, Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts. © The State of Queensland (Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts) 2012. Copyright inquiries should be addressed to <[email protected]> or the Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts, 111 George Street, Brisbane QLD 4000. Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3224 8412. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. large print or audiotape) on request for people with vision impairment; phone +61 7 3224 8412 or email <[email protected]>. ISBN: 978-1-920928-21-6 Citation This work may be cited as: Wilson, P.R. and Taylor, P.M. (2012) Land Zones of Queensland. Queensland Herbarium, Queensland Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts, Brisbane. 79 pp. Front Cover: Design by Will Smith Images – clockwise from top left: ancient sandstone formation in the Lawn Hill area of the North West Highlands bioregion – land zone 10 (D. -

Australia: Perth and South East Queensland

Graham Sansom and Jeremy Dawkins UTS Centre for Local Government 22.5m population; Growth 1.5-2%pa; 60% in 6 major metro regions; GDP US$60,000 per capita Population of Population of Population Metropolitan Metropolitan ‘central city’ local State of state region region government 2010 2008/09 2008/09 New South City of Sydney: Sydney 7,238,819 5,316,379 Wales 177,000 City of Hobart: Tasmania Hobart 507,626 205,566 49,887 South East Brisbane City: Queensland 4,516,361 2,706,302 Queensland 1,052,458 Western City of Perth: Perth 2,296,411 1,519,510 Australia 17,093 City of Melbourne: Victoria Melbourne 5,547,527 4,014,361 89,759 South City of Adelaide: Adelaide 1,644,642 1,275,041 Australia 19,444 Metropolitan Region Absolute Percentage Population Population (Statistical Divisions Growth Growth 1996 2006 included) 1996 - 2006 1996 - 2006 Sydney (Sydney SD, Hunter SD, 4,808,237 5,316,379 508,142 10.57% Illawarra SD) Melbourne (Melbourne SD, Barwon 3,522,797 4,014,361 491,564 13.95% SD) South East Queensland (Brisbane SD, Gold Coast 2,138,215 2,706,302 568,087 26.57% SD, Sunshine Coast SD, West Moreton SD) Perth 1,295,092 1,519,510 224,418 17.33% (Perth SD) Adelaide (Adelaide SD, Outer 1,182,768 1,275,041 92,273 7.80% Adelaide SD) Hobart 195,718 205,566 9,846 5.03% (Greater Hobart SD) Selected regions Both typical and distinctive Dominant population centres in their states (SEQ somewhat less so) Mostly developed in last 30-50 years: car-based ‘sprawl’ but recent focus on increased densities and inner suburban renewal with apartment living -

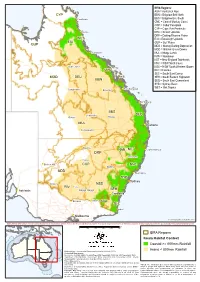

Koala Context

IBRA Regions: AUA = Australian Alps CYP BBN = Brigalow Belt North )" Cooktown BBS = Brigalow Belt South CMC = Central Mackay Coast COP = Cobar Peneplain CYP = Cape York Peninsula ") Cairns DEU = Desert Uplands DRP = Darling Riverine Plains WET EIU = Einasleigh Uplands EIU GUP = Gulf Plains GUP MDD = Murray Darling Depression MGD = Mitchell Grass Downs ") Townsville MUL = Mulga Lands NAN = Nandewar NET = New England Tablelands NNC = NSW North Coast )" Hughenden NSS = NSW South Western Slopes ") CMC RIV = Riverina SEC = South East Corner MGD DEU SEH = South Eastern Highlands BBN SEQ = South East Queensland SYB = Sydney Basin ") WET = Wet Tropics )" Rockhampton Longreach ") Emerald ") Bundaberg BBS )" Charleville )" SEQ )" Quilpie Roma MUL ") Brisbane )" Cunnamulla )" Bourke NAN NET ") Coffs Harbour DRP ") Tamworth )" Cobar ") Broken Hill COP NNC ") Dubbo MDD ") Newcastle SYB ") Sydney ") Mildura NSS RIV )" Hay ") Wagga Wagga SEH Adelaide ") ") Canberra ") ") Echuca Albury AUA SEC )" Eden ") Melbourne © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 INDICATIVE MAP ONLY: For the latest departmental information, please refer to the Protected Matters Search Tool and the Species Profiles & Threats Database at http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/index.html km 0 100 200 300 400 500 IBRA Regions Koala Habitat Context Coastal >= 800mm Rainfall Produced by: Environmental Resources Information Network (2014) Inland < 800mm Rainfall Contextual data source: Geoscience Australia (2006), Geodata Topo 250K Topographic Data and 10M Topographic Data. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2012). Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA), Version 7. Other data sources: Commonwealth of Australia, Bureau of Meteorology (2003). Mean annual rainfall (30-year period 1961-1990). Caveat: The information presented in this map has been provided by a Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (2013). -

State Coastal Management Plan

Schedule 1: Regional overviews The Queensland coast has been subdivided into eleven coastal regions for the purpose of preparing regional coastal plans. The regions’ boundaries are based on coastal local government boundaries. The overview for each region generally describes the region, its coastal resources, existing management and administration arrangements, and the key coastal management issues.18 The eleven coastal regions are illustrated in map 1. Map 3 shows the terrestrial and marine bioregions referred to in this schedule. Marine Terrestrial 145 E 140 E yy Arafura 1 Cape York Peninsula Carpentaria 2 Gulf Plains yy 10 S 1 1 Wellesley 3 Einasleigh Uplands Karumba-Nassau 4 Wet Tropical Rainforest yy yyyyyyyyy West Cape York 5 Mount Isa Inlier 1 Torres Strait 6 Gulf Fall Upland yy yyyyyyyyy | 1 East Cape York 7 Mitchell Grass Downs Weipa Ribbons 8 yyyyyyyyy Brigalow Belt North 1 1 Wet Tropic Coast 9 Central Queensland Coast Coen yyyyyyyyyy1 yyCentral Reef 10 Desert Uplands Lucinda-Mackay Coast 11 South Brigalow 1 1 yyyyyyy1 Mackay-Capricorn 12 South-east Queensland 15 S 1 1 Cooktown Pompey-Swains 13 Simpson-Strzelecki Dunefields yyyyyyyyyyyyyyy 2 4 Shoalwater Coast 14 NSW North Coast 3 Tweed-Moreton 2 2 15 Darling-Riverine Plain yyyyyy yyyCairns yy zy 2 Outer Provinces 2 16 New England Tableland 2 Atherton 4 6 2 Normanton 17 3 4 Nandewar yyyBurketownyyy yyy 2 3 18 Channel Country 6 Einasleigh 4 2 3 Ingham 2 19 Mulga Lands yyyyyyyy 2 3 5 3 Townsville {|{ 2 Ayr 5 2 yyyyyCharters Towers 8 20 S 3 Bowen 20 -

There Is a Huge Regional Literature on Weed Identification and Management, in On-Line and Hardcopy Formats

WEEDS There is a huge regional literature on weed identification and management, in on-line and hardcopy formats. Only a fraction of the total is shown here. Websites of local Councils, Natural Resource Management bodies, and Departments of Primary Industry/Agriculture often have identification and management information for common or priority species. State and territory on-line Information & Identification Systems covering large sets of naturalised taxa [For some states these on-line systems are as yet incomplete in coverage. For these cases, see recent Floras and other resources in the relevant sections of this bibliography.] WEEDS – NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL Randall, RP (2017) A global compendium of weeds. 3rd edition. R.P. Randall. ISBN: 9780646967493. ELECTRONIC RESOURCE, ON-LINE (free PDF): https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313645439_A_Global_Compendium_of_Weeds_Third_E dition (very large PDF file, c. 68 MB, 3,659 pages). Not an identification resource as such, but a very comprehensive directory of weeds by currently recognised names and authoritative references. Weeds in Australia website. (Commonwealth Dept of Environment – ongoing). ELECTRONIC RESOURCE – ON-LINE, Interactive: http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/invasive/weeds/index.html http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/invasive/weeds/identification/index.html Provides a range of information on weed issues, including different options for identification. The Weed Identification Tool: simple search on flower colour, growth form, and State. Weed Search