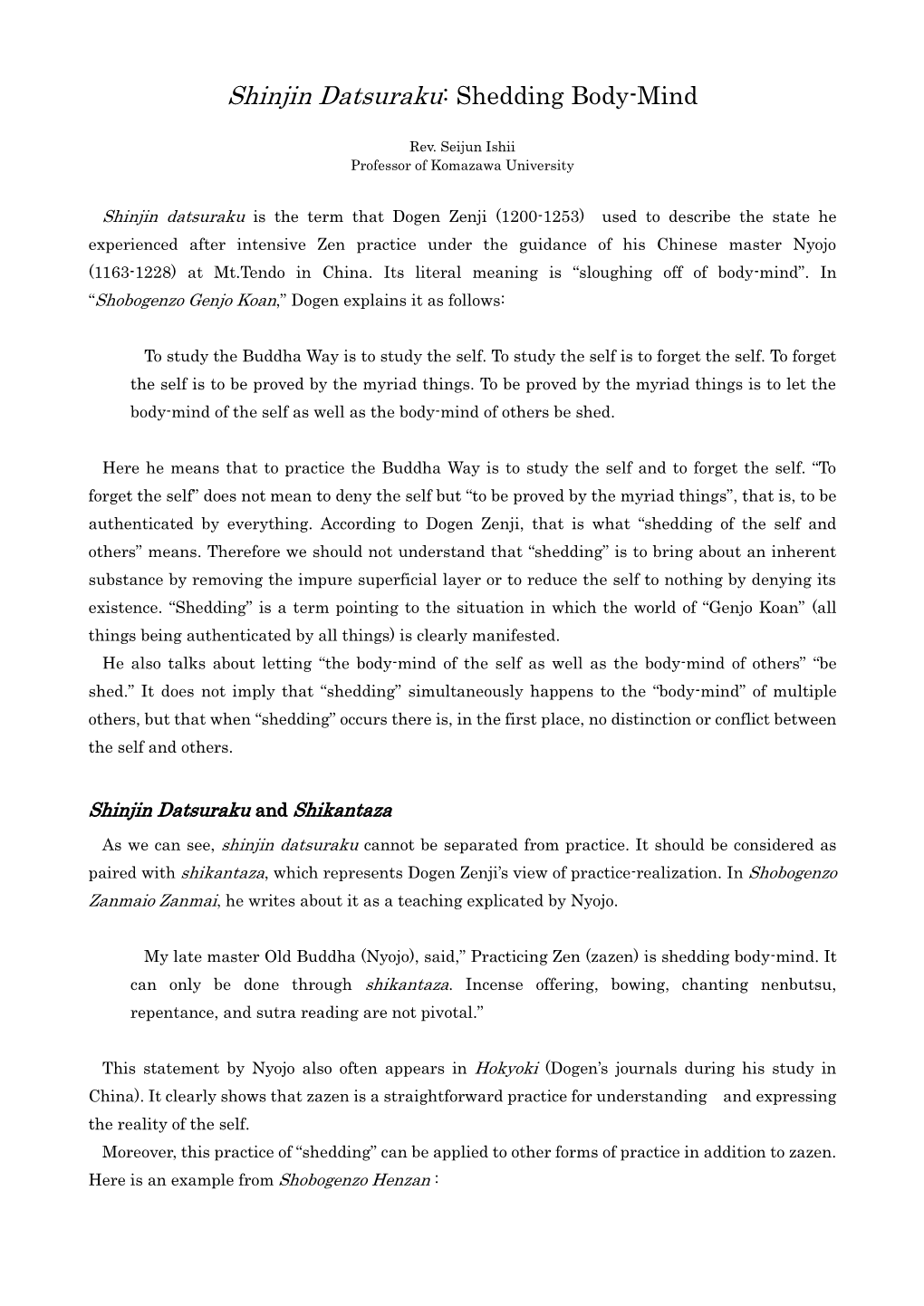

Shinjin Datsuraku: Shedding Body-Mind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CEREMONY of ATONEMENT ZENDO VERSION – Doan’S Book Last Updated 09/2009

CEREMONY OF ATONEMENT ZENDO VERSION – Doan’s Book Last Updated 09/2009 Positions: Officiant, Chanter, Doan, Jikido, Jisha, Sogei, Monitors Before Ceremony: Set out two single hako on two small tables at outside at foot of Main Entrance. Sangha will purify upon entering the Zendo. At 7:25 p.m. bring one hako in and place in back gaitan – to be used in Zendo for ceremony Doan has large kesu and bai from Kaisando, also small kesu & bai, inkin and the podium from the Buddha Hall for the Doan book; Set out a long stick of incense on the altar; have tall lectern ready in front gaitan with Chanter book; place talking piece on altar and set out Precepts Handouts in zendo; set up charcoal lighting materials – lighter, candle, tongs, charcoal – in the back gaitan. Be sure set up includes a seat for the officiant to sit in during personal atonements. * * * * * * * Jikido: Prepare zendo: light candle & turn on lights at usual time Do three rounds on the han Start 15 minute zazen period; then hit bell once and Announce: “PREPARE FOR CEREMONY OF ATONEMENT” Hang up Fusatsu plaque Jisha: As soon as announcement is made, turn on light above altar, light and place two waiting sticks in the incense bowl. Dennans: Move zabutans in front row (North East) so that Roshi’s seat is Where the Head Monitor’s seat is normally (refer to setup diagram). Also encourage people seated in the back to move to forward seats (i.e., fill seats from the front). * * * * * * * Atonement Ceremony – Chanter Book 1 2/27/2008 Officiant Entry: (usual entry) Officiant enters (Doan chings at entry, halfway to haishiki, and at bow at haishiki) and goes up to altar to offer stick incense. -

Publications Received by the Regional Editor for South-Asia (From April 2001 to November 2002)

Publications received by the regional editor for South-Asia (from April 2001 to November 2002) Objekttyp: Group Zeitschrift: Asiatische Studien : Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft = Études asiatiques : revue de la Société Suisse-Asie Band (Jahr): 57 (2003) Heft 1 PDF erstellt am: 10.10.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch PUBLICATIONS RECEIVED by the regional editor for South-Asia (from April 2001 to November 2002) Adachi, Toshihide (2001): '"Hearing Amitäbha's name' in the Sukhâvatî-vyûha." Buddhist and Pure Land Studies. Felicitation volume for Takao Kagawa on his Seventieth Birthday. Kyoto: Nagata-bunshö -do. Pp. 21-38. -

Zen Heart Sangha Jikido Schema Sesshin

Zen Heart Sangha Jikido schema Sesshin Als Jikido heb je tot taak om de zendo te beheren, de meditatie volgens het schema gaande te houden en vooral om de aanwezigen in staat te stellen zich helemaal aan hun beoefening te wijden zonder zich met andere dingen bezig te hoeven houden. Je stelt je beoefening dus voor een groot deel ten dienste van de anderen. Je beoefening als Jikido is, om je zo veel mogelijk bewust te zijn van de deelnemers en van de gang van zaken in de zendo. Je richt je op het welzijn van de deelnemers en op wat er gaande is in de zendo en neemt daar ook mede de verantwoordelijkheid voor. Je bent niet alleen verantwoordelijk voor de zendo, je bent ook de gastheer/vrouw in de zendo en je belichaamt het praktisch functioneren van Zazen. Je bent de persoonlijke expressie van het niet-persoonlijke, altijd klaar om te handelen naar gelang de situatie vergt. Je doet gewoon wat gedaan moet worden vanuit een milde, open, responsieve staat van zijn. Als Jikido zorg je ervoor dat je op tijd in de zendo bent. Je regelt de verlichting, de temperatuur en de ventilatie, en checkt eventueel of het altaar op orde is (bloemen, kaars, wierookbrander, wierookstaafjes). Je volgt nauwkeurig het tijdschema zonder inflexibel te zijn. Je zoekt op eigen initiatief de leraar of de Jisha op om het schema up to date te houden en je wordt door de leraar ook zo goed mogelijk op de hoogte gehouden van eventuele veranderingen. Eerste zitperiode 0700 zazen (40m zen - 10m kinhin - 30m zen - 10m kinhin - 30m zen) 0630 Wekken. -

Zen Classics: Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism

Zen Classics: Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism STEVEN HEINE DALE S. WRIGHT, Editors OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Zen Classics This page intentionally left blank Zen Classics Formative Texts in the History of Zen Buddhism edited by steven heine and dale s. wright 1 2006 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright ᭧ 2006 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zen classics: formative texts in the history of Zen Buddhism / edited by Steven Heine and Dale S. Wright. p. cm Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: The concept of classic literature in Zen Buddhism / Dale S. Wright—Guishan jingce and the ethical foundations of Chan practice / Mario Poceski—A Korean contribution to the Zen canon the Oga hae scorui / Charles Muller—Zen Buddhism as the ideology of the Japanese state / Albert Welter—An analysis of Dogen’s Eihei goroku / Steven Heine—“Rules of purity” in Japanese Zen / T. -

Guide to Form 5Th Draft

Form Guide StoneWater Zen Sangha Form Guide Keizan Sensei on form Page 3 Introduction to the Guide 4 Part One: Essentials 5 Entering the zendo 6 Sitting in the zendo 7 Kin-Hin 8 Interviews 9 Teacher's entrance and exit 10 An Introduction to Service 12 Part Two: Setting up and Key Roles 14 The Altar, Layout of the zendo 15 Key Roles in the zendo 16 Jikido 16 Jisha 18 Chiden, Usher, Monitor 19 Service Roles 20 Ino 20 Doan 22 Mokugyo 23 Dennan, Jiko 24 Sogei 25 Glossary 26 Sources 28 September 2012 Page 2 StoneWater Zen Sangha Form Guide Keizan Sensei on form This Form Guide is intended as a template that can be used by all StoneWater Zen sangha members and groups associated with StoneWater such that we can, all together, maintain a uniformity and continuity of practice. The form that we use in the zendo and for Zen ceremonies is an important part of our practice. Ceremony, from the Latin meaning 'to cure,' acts as a reminder of how much there is outside of our own personal concerns and allows us to reconnect with the profundity of life and to show our appreciation of it. Form is a vehicle you can use for your own realisation rather than something you want to make fit your own views. To help with this it is useful to remember that the structure though fixed is ultimately empty. Within meditation and ceremony form facilitates our moving physically and emotionally from our usual outward looking personal concerns to the inner work of realisation and change. -

Jikido Takasaki, a Study on the Ratnagotravibhaga (Uttaratantra)

Jikido Takasaki, A Study on the Ratnagotravibhaga (Uttaratantra) Johannes Rahder Professor of Yale University Jikido Takasaki, A study on the Ratnagotravibhaga (Uttaratantra), being a Treatise on the Tathagatagarbha Theory of Mahayana Buddhism, including a critical Introduction, a Synopsis of the text, a Translation from the original Sanskrit text, in comparison with its Tibetan & Chinese versions, critical Notes (more than 2000), Appendixes and Indexes. 13+ 439 pages. Serie Orientale Roma Vol. 33. Roma, Istituto Italiano per it Medio ed Estremo Oriente, 1966. In this monumental work Dr. Takasaki made a major contribution to our knowledge of a Buddhist monistic, absolutistic, eternalistic, subs- tantialistic philosophical system, which Erich Frauwallner (Professor at the Univ. of Vienna) in his book "Philosophie des Buddhismus" p. 255-264 (Berlin, Akademie Verlag 1958, 436 pages) called "Die Schule Saramatis", dat- ed in the middle of the third century and placed in an intermediate position between the relativistic Madhyamaka and idealistic Yogacara systems. Frauwallner, whose above listed sourcebook of Buddhist philo- sophy is not mentioned in Takasaki's book, brought the Mahayanasra- ddhotpada-sastra (Kishinron) into close association with: the Ratnagotra- vibhaga because they share both the Matrix (Garbha) theory (Takasaki p. 53). Takasaki's annotated and well indexed English translation owes a great deal to E. E. Obermiller's English translation from the Tibetan version, published in Acta Orientalia ninth volume (1931) p. 81-306. Ho- wever, the late E. E. Obermiller (lifespan: 1901-1935) did not know the Sanskrit original, published in Patna in 1950, and could not read the -421- Jikido Takasaki, A Study on the Ratnagotravibhaga (J. -

Brahmanism and Buddhism: Two Antithetic Conceptions of Society In

BRAHMANISMANDBUDDHISM: TWOANTITHETICCONCEPTIONSOFSOCIETY INANCIENTINDIA FernandoTolaandCarmenDragonetti (InstituteofBuddhistStudiesFoundation ,FIEB/CONICET/Argentina) Introduction Brahmanism and Buddhism gave rise in India to two forms of society strongly opposed. The philosophical principles maintained by Brahmanism and Buddhism, their conceptionsof man and of the destiny of man, which were the foundationof those two antithetictypesofsociety,hadtobealsoequallyopposed.1 BuddhismmeantinfaceofBrahmanismaprofoundsocialchange,whichcouldbe called ‘revolutionary’, if itwerenot that this term isgenerally associated with violence, violencethatwascompletelyalientoBuddhism.LetusexpressthisintermsofAlbrecht Weber,thegreatGermanIndologist(1825-1901) 2,inourtranslationfromGerman: “Buddhismis,initsorigin,oneofthemostmagnificentandradicalreactionsinfavor of the universal human rights of the individual against the oppressing tyranny of the pretendedprivilegesofdivineorigin,ofbirth,andofclass. Buddhismistheworkofasingleman,Buddha,whointhebeginningofthe6 th century B. C., in Eastern India, rose up against the Brahmanical hierarchy, and, thanks to the simplicityandethicalforceofHisTeaching,provokedacompleteruptureofIndianpeople withtheirpast. InfaceofthehopelessdistortionsofallhumanfeelingsthattheBrahmanicalestate andcast-systembroughtwiththem,infaceoftheardentdesireofliberationnotonlyfrom earthlyindividualexistencethatadoptedforthegreatpartofthepeopleonlysopainfuland oppressingforms,butalsofromtheeternallychangingsystemofreincarnations,suchas -

Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation Carl Bielefeldt

cover next page > title: Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation author: Bielefeldt, Carl. publisher: University of California Press isbn10 | asin: 0520068351 print isbn13: 9780520068353 ebook isbn13: 9780585111933 language: English subject Dogen,--1200-1253, Meditation--Zen Buddhism, Sotoshu- -Doctrines, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Fukan zazengi. publication date: 1988 lcc: BQ9449.D657B53 1988eb ddc: 294.3/443 subject: Dogen,--1200-1253, Meditation--Zen Buddhism, Sotoshu- -Doctrines, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Fukan zazengi. cover next page > < previous page page_i next page > Page i This volume is sponsored by the Center for Japanese Studies University of California, Berkeley < previous page page_i next page > cover next page > title: Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation author: Bielefeldt, Carl. publisher: University of California Press isbn10 | asin: 0520068351 print isbn13: 9780520068353 ebook isbn13: 9780585111933 language: English subject Dogen,--1200-1253, Meditation--Zen Buddhism, Sotoshu- -Doctrines, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Fukan zazengi. publication date: 1988 lcc: BQ9449.D657B53 1988eb ddc: 294.3/443 subject: Dogen,--1200-1253, Meditation--Zen Buddhism, Sotoshu- -Doctrines, Dogen,--1200-1253.--Fukan zazengi. cover next page > < previous page page_iii next page > Page iii Dogen's Manuals of Zen Meditation Carl Bielefeldt University of California Press Berkeley, Los Angeles, London < previous page page_iii next page > < previous page page_iv next page > Page iv To Yanagida Seizan University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1988 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bielefeldt, Carl. Dogen's manuals of Zen meditation Carl Bielefeldt. p. cm. Bibliography: p. ISBN 0-520-06835-1 (ppk.) 1. Dogen, 1200-1253. -

Beginning: Return

Soto Zen Buddhism in Australia December 2020. Issue 82 BEGINNING: RETURN TEISHO LEARNING BUDDHA’S WAY BEING THE SHUSO Ekai Korematsu Osho Ekai Korematsu Osho Marisha Jiho Rothman QUANG MINH TEMPLE ZENDO MY TEACHER AND FRIEND BOWING TO THE ZEN ZOOM THEATRE Karen Threlfall Christine Maingard Annie Bolitho MYOJU IS A PUBLICATION OF JIKISHOAN ZEN BUDDHIST COMMUNITY INC Editorial Myoju Welcome to this edition of Myoju magazine. Our theme Editor: Ekai Korematsu Osho for this issue is Beginning: Return. Publications Committee: Shona Innes, Margaret Lynch, Jessica Cummins, Robin Laurie, Sangetsu Carter, Iris This has been a remarkable year for the Tokozan- Dillow, Lachlan Macnish, John Chadderton Jikishoan community. All of Jikishoan’s practice activities Myoju Coordinator: Margaret Lynch and programs were suspended in March due to COVID-19 Production: Sangetsu Carter, Lachlan Macnish restrictions. Soon after, Ekai Osho launched the Online Website Manager: Lee-Anne Armitage Home Learning and Retreat Program. In the same way as IBS Teaching Schedule: Shona Innes we practice kinhin—walking meditation—the community Jikishoan Calendar of Events: Shona Innes has moved ahead, one small step at a time, to arrive to the Contributors: Ekai Korematsu Osho, Marisha Rothman, close of the year, having completed three six-week long Christine Maingard, Annie Bolitho, Karen Threlfall, online retreats. John Chadderton, Caleb Mortensen, Lachlan Macnish, The sangha has learned many things over the last eight Candace Schreiner, Donne Soukchareun months, and we have grown in strength as a result. Online Cover Image: Returning to Tokozan Home Temple— technology has enabled the growth of our regular practice photographed by Lachlan Macnish—22 June 2019 community, which now includes students from interstate and overseas. -

Buddhist Phenomenology and the Problem of Essence

Comparative Philosophy Volume 7, No. 1 (2016): 59-89 Open Access / ISSN 2151-6014 www.comparativephilosophy.org BUDDHIST PHENOMENOLOGY AND THE PROBLEM OF ESSENCE JINGJING LI ABSTRACT: In this paper, I intend to make a case for Buddhist phenomenology. By Buddhist phenomenology, I mean a phenomenological interpretation of Yogācāra’s doctrine of consciousness. Yet, this interpretation will be vulnerable if I do not justify the way in which the anti-essentialistic Buddhist philosophy can countenance the Husserlian essence. I dub this problem of compatibility between Buddhist and phenomenology the “problem of essence”. Nevertheless, I argue that this problem will not jeopardize Buddhist phenomenology because: (1) Yogācārins, especially later Yogācārins represented by Xuan Zang do not articulate emptiness as a negation but as an affirmation of the existent; (2) Husserl’s phenomenological essence is not a substance that Yogācārins reject but the ideal sense (Sinn) that Yogācārins also stress. After resolving the problem of essence, I formulate Buddhist phenomenology as follows: on the epistemological level, it describes intentional acts of consciousness; on the meta-epistemological level, it entails transcendental idealism. Keywords: essence, emptiness, later Yogācāra, transcendental idealism, Buddhist phenomenology 1. INTRODUCTION In Ideas1, Husserl defines phenomenology as the science of essence, not the science of matters of facts (Hua 3/5). This demarcation marks his turn from descriptive phenomenology (the study that factually analyzes real psychological phenomena) to transcendental phenomenology (the theory that explains essential ideal conditions that make real psychological phenomena possible). Regardless of this turn, Husserl uses phenomenology as the approach to consciousness. He describes human consciousness to be the intentional awareness constituted by subjects in their interaction with objects that appear as mental phenomena. -

Report of the XVI Th Congress of the International Association Of

Report of the XVI th Congress of the International Association of Buddhist Studies Ulrich Pagel General Secretary, IABS The XVIth Congress of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (IABS) took place at Dharma Drum Buddhist College in Jinshan, New Taipei City (Taiwan) from 20 to 25 June 2011. Attesting to the steady increase of interest in Buddhist Studies worldwide, participation at this IABS congress exceeded once again previous registration figures. More than seven-hundred delegates, arriving from all corners of the globe, joined the proceedings at Dharma Drum Buddhist College over a period of six days. The Congress was prepared by a local planning committee, led with great compe- tence by the venerable Jenjou Hung and Professor William Magee. The team in charge of organization of the Congress drew on the support of a very large and well-prepared team of staff and students, including a veritable army of volunteers drawn from the Saṅgha, many of whom had travelled to Jinshan from afar for this very pur- pose. The local arrangements and hospitality were truly exemplary and set a new benchmark for all future congresses. The academic program commenced with a convocation cere- mony at which the IABS President Professor Dr Scherrer-Schaub delivered her address, entitled: ‘Perennial Encounters – The Simile of the Painter and the Irruption of Representation in Indian Buddhism.’ This was followed by a keynote address of Professor Tom Tillemans (IABS General Secretary, 2002–2008) with the title ‘Mind, Dharmakīrti and Madhyamaka.’ Over the course of the next five days, IABS delegates delivered a total of 565 papers, probing a wide range of issues in Buddhist studies. -

Proquest Dissertations

A study of Master Yinshun's hermeneutics: An interpretation of the tathagatagarbha doctrine Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hurley, Scott Christopher Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 19:57:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/279857 INFORMATIOH TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in ttiis copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge.