Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

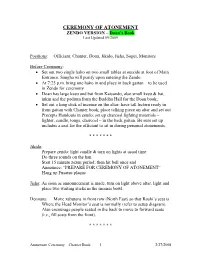

CEREMONY of ATONEMENT ZENDO VERSION – Doan’S Book Last Updated 09/2009

CEREMONY OF ATONEMENT ZENDO VERSION – Doan’s Book Last Updated 09/2009 Positions: Officiant, Chanter, Doan, Jikido, Jisha, Sogei, Monitors Before Ceremony: Set out two single hako on two small tables at outside at foot of Main Entrance. Sangha will purify upon entering the Zendo. At 7:25 p.m. bring one hako in and place in back gaitan – to be used in Zendo for ceremony Doan has large kesu and bai from Kaisando, also small kesu & bai, inkin and the podium from the Buddha Hall for the Doan book; Set out a long stick of incense on the altar; have tall lectern ready in front gaitan with Chanter book; place talking piece on altar and set out Precepts Handouts in zendo; set up charcoal lighting materials – lighter, candle, tongs, charcoal – in the back gaitan. Be sure set up includes a seat for the officiant to sit in during personal atonements. * * * * * * * Jikido: Prepare zendo: light candle & turn on lights at usual time Do three rounds on the han Start 15 minute zazen period; then hit bell once and Announce: “PREPARE FOR CEREMONY OF ATONEMENT” Hang up Fusatsu plaque Jisha: As soon as announcement is made, turn on light above altar, light and place two waiting sticks in the incense bowl. Dennans: Move zabutans in front row (North East) so that Roshi’s seat is Where the Head Monitor’s seat is normally (refer to setup diagram). Also encourage people seated in the back to move to forward seats (i.e., fill seats from the front). * * * * * * * Atonement Ceremony – Chanter Book 1 2/27/2008 Officiant Entry: (usual entry) Officiant enters (Doan chings at entry, halfway to haishiki, and at bow at haishiki) and goes up to altar to offer stick incense. -

Searching for a Possibility of Buddhist Hermeneutics: Two Exegetic Strategies in Buddhist Tradition

Searching for a Possibility of Buddhist Hermeneutics: Two Exegetic Strategies in Buddhist Tradition Sumi Lee University of California, Los Angeles One of the main concerns in religious studies lies in hermeneutics 1 : While interpreters of religion, as those in all other fields, are doomed to perform their work through the process of conceptualization of their subjects, religious reality has been typically considered as transcending conceptual categorization. Such a dilemma imposed on the interpreters of religion explains the dualistic feature of the Western hermeneutic history of religion--the consistent attempts to describe and explain religious reality on the one hand and the successive reflective thinking on the limitation of human knowledge in understanding ultimate reality on the other hand.2 Especially in the modern period, along with the emergence of the methodological reflection on religious studies, the presupposition that the “universally accepted” religious reality or “objectively reasoned” religious principle is always “over there” and may be eventually disclosed through refined scientific methods has become broadly questioned and criticized. The apparent tension between the interpreter/interpretation and the object of interpretation in religious studies, however, does not seem to have undermined the traditional Buddhist exegetes’ eagerness for their work of expounding the Buddhist teachings: The Buddhist exegetes and commentators not only devised various types of systematic and elaborate literal frameworks such as logics, theories, styles and rhetoric but also left the vast corpus of canonical literatures in order to transmit their religious teaching. The Buddhist interpreters’ enthusiastic attitude in the composition of the literal works needs more attention because they were neither unaware of the difficulty of framing the religious reality into the mold of language nor forced to be complacent to the limited use of language about the reality. -

The Scientific Evidence of the Buddhist Teaching's Separation Body

International Journal of Philosophy 2015; 3(2): 12-23 Published online July 2, 2015 (http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijp) doi: 10.11648/j.ijp.20150302.11 ISSN: 2330-7439 (Print); ISSN: 2330-7455 (Online) The Scientific Evidence of the Buddhist Teaching’s Separation Body and Mind When Humans and Animals Die Jargal Dorj ONCH-USA, Co., Chicago Email address: [email protected] To cite this article: Jargal Dorj. The Scientific Evidence of the Buddhist Teaching’s Separation Body and Mind When Humans and Animals Die. International Journal of Philosophy . Vol. 3, No. 2, 2015, pp. 12-23. doi: 10.11648/j.ijp.20150302.11 Abstract: This article proves that the postulate "the body and mind of humans and animals are seperated, when they die" has a theoretical proof, empirical testament and has its own unique interpretation. The Buddhist philosophy assumes that there are not-eternal and eternal universe and they have their own objects and phenomena. Actually, there is also a neutral universe and phenomena. We show, and make sure that there is also a neutral phenomena and universe, the hybrid mind and time that belongs to neutral universe. We take the Buddhist teachings in order to reduce suffering and improve rebirth and, and three levels of Enlightenment. Finally, due to the completion evidence of the Law of Karma as a whole, it has given the conclusion associated with the Law of Karma. Keywords: Body, Spirit, Soul, Mind, Karma, Buddha, Nirvana, Samadhi “If there is any religion that would cope with modern may not be able to believe in it assuming this could be a scientific needs, it would be Buddhism” religious superstition. -

The Development of Prajna in Buddhism from Early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita System: with Special Reference to the Sarvastivada Tradition

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2001 The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition Qing, Fa Qing, F. (2001). The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/15801 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/40730 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Dcvelopmcn~of PrajfiO in Buddhism From Early Buddhism lo the Praj~iBpU'ranmirOSystem: With Special Reference to the Sarv&tivada Tradition Fa Qing A DISSERTATION SUBMIWED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY. ALBERTA MARCI-I. 2001 0 Fa Qing 2001 1,+ 1 14~~a",lllbraly Bibliolheque nationale du Canada Ac uisitions and Acquisitions el ~ibqio~raphiiSetvices services bibliogmphiques The author has granted anon- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pernettant a la National Library of Canada to Eiblioth&quenationale du Canada de reproduce, loao, distribute or sell reproduire, priter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

On the Penetration of Dharmakya and Dharmadesana -Based on the Different Ideas of Dharani and Tathagatagarbha

On the Penetration of Dharmakya and Dharmadesana -based on the different ideas of dharani and tathagatagarbha- Kakusho U jike We can recognize many developements of the Buddhakaya theory in the evo- lution of Mahayana thought systems which are related to various doctrines such as the Vi jnanavada, etc. In my opinion, the Buddhakaya theory stressed how the Bodhisattvas or any living being can meet the eternal Buddha and enjoy the benefits of instruction on enlightenment from him. In the Mahayana, the concept of truth also developed parallel with the Bud- dhakaya theory and the most important theme for the Mahayanist is how to understand the nature of the Buddha who became one with the truth (dharma- kaya). That is to say, the problem of how to realize the truth is the same pro- blem of how to meet the eternal Buddha with the joy of uniting oneself with the realm of the Buddha's enlightenment (dharmadhatu). In this situation one's faculties are always tested in the effort to encounter and understand the real teaching of the Buddha, because the truth revealed by the Buddha is quite high and deep, going beyond the intellect of ordinary people The Buddha's teaching is understood only by eminent Bodhisattvas who possess the super power of hearing the subtle voice of the Buddha. One of the excellent means of the Bodhisattvas for hearing, memorizing, and preaching etc., the teachings of the Buddha is considered to be the dharani. Dharani seemed to appear at first in the Prajnaparamita-sutras or in other Sutras having close relation to theme). -

Buddhist Spiritual Practices

Buddhist Spiritual Practices Thinking with Pierre Hadot on Buddhism, Philosophy, and the Path Edited by David V. Fiordalis Mangalam Press Berkeley, CA Mangalam Press 2018 Allston Way, Berkeley, CA USA www.mangalampress.org Copyright © 2018 by Mangalam Press. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be copied, reproduced, published, distributed, or stored electronically, photographically, or optically in any form without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-0-89800-117-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018930282 Mangalam Press is an imprint of Dharma Publishing. The cover image depicts a contemporary example of Tibetan Buddhist instructional art: the nine stages on the path of “calming” (śamatha) meditation. Courtesy of Exotic India, www.exoticindia.com. Used with permission. ♾ Printed on acid-free paper. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Printed in the USA by Dharma Press, Cazadero, CA 95421 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 David V. Fiordalis Comparisons with Buddhism Some Remarks on Hadot, Foucault, and 21 Steven Collins Schools, Schools, Schools—Or, Must a Philosopher be Like a Fish? 71 Sara L. McClintock The Spiritual Exercises of the Middle Way: Madhyamakopadeśa with Hadot Reading Atiśa’s 105 James B. Apple Spiritual Exercises and the Buddhist Path: An Exercise in Thinking with and against Hadot 147 Pierre-Julien Harter the Philosophy of “Incompletion” The “Fecundity of Dialogue” and 181 Maria Heim Philosophy as a Way to Die: Meditation, Memory, and Rebirth in Greece and Tibet 217 Davey K. -

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia

Buddhism and Responses to Disability, Mental Disorders and Deafness in Asia. A bibliography of historical and modern texts with introduction and partial annotation, and some echoes in Western countries. [This annotated bibliography of 220 items suggests the range and major themes of how Buddhism and people influenced by Buddhism have responded to disability in Asia through two millennia, with cultural background. Titles of the materials may be skimmed through in an hour, or the titles and annotations read in a day. The works listed might take half a year to find and read.] M. Miles (compiler and annotator) West Midlands, UK. November 2013 Available at: http://www.independentliving.org/miles2014a and http://cirrie.buffalo.edu/bibliography/buddhism/index.php Some terms used in this bibliography Buddhist terms and people. Buddhism, Bouddhisme, Buddhismus, suffering, compassion, caring response, loving kindness, dharma, dukkha, evil, heaven, hell, ignorance, impermanence, kamma, karma, karuna, metta, noble truths, eightfold path, rebirth, reincarnation, soul, spirit, spirituality, transcendent, self, attachment, clinging, delusion, grasping, buddha, bodhisatta, nirvana; bhikkhu, bhikksu, bhikkhuni, samgha, sangha, monastery, refuge, sutra, sutta, bonze, friar, biwa hoshi, priest, monk, nun, alms, begging; healing, therapy, mindfulness, meditation, Gautama, Gotama, Maitreya, Shakyamuni, Siddhartha, Tathagata, Amida, Amita, Amitabha, Atisha, Avalokiteshvara, Guanyin, Kannon, Kuan-yin, Kukai, Samantabhadra, Santideva, Asoka, Bhaddiya, Khujjuttara, -

Time and Eternity in Buddhism

TIME AND ETERNITY IN BUDDHISM by Shoson Miyamoto This essay consists of three main parts: linguistic, historical and (1) textual. I. To introduce the theory of time in Buddhism, let us refer to the Sanskrit and Pali words signifying "time". There are four of these: sa- maya, kala, ksana (khana) and adhvan (addhan). Samaya means a coming together, meeting, contract, agreement, opportunity, appointed time or proper time. Kala means time in general, being employed in the term kala- doctrine or kala-vada, which holds that time ripens or matures all things. In its special meaning kala signifies appointed or suitable time. It may also mean meal-time or the time of death, since both of these are most critical and serious times in our lives. Death is expressed as kala-vata in Pali, that is "one has passed his late hour." Ksana also means a moment, (1) The textual part is taken from the author's Doctoral Dissertation: Middle Way thought and Its Historical Development. which was submitted to the Imperial University of Tokyo in 1941 and published in 1944 (Kyoto: Hozokan). Material used here is from pp. 162-192. Originally this fromed the second part of "Philosophical Studies of the Middle," which was delivered at the Annual Meeting of the Philosophical Society, Imperial University of Tokyo, in 1939 and published in the Journal of Philosophical Studies (Nos. 631, 632, 633). Since at that time there was no other essay published on the time concept in Buddhism, these earlier studies represented a new and original contribution by the author. Up to now, in fact, such texts as "The Time of the Sage," "The Pith and Essence" have survived untouched. -

Publications Received by the Regional Editor for South-Asia (From April 2001 to November 2002)

Publications received by the regional editor for South-Asia (from April 2001 to November 2002) Objekttyp: Group Zeitschrift: Asiatische Studien : Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft = Études asiatiques : revue de la Société Suisse-Asie Band (Jahr): 57 (2003) Heft 1 PDF erstellt am: 10.10.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch PUBLICATIONS RECEIVED by the regional editor for South-Asia (from April 2001 to November 2002) Adachi, Toshihide (2001): '"Hearing Amitäbha's name' in the Sukhâvatî-vyûha." Buddhist and Pure Land Studies. Felicitation volume for Takao Kagawa on his Seventieth Birthday. Kyoto: Nagata-bunshö -do. Pp. 21-38. -

The Depth Psychology of the Yogacara

Aspects of Buddhist Psychology Lecture 42: The Depth Psychology of the Yogacara Reverend Sir, and Friends Our course of lectures week by week is proceeding. We have dealt already with the analytical psychology of the Abhidharma; we have dealt also with the psychology of spiritual development. The first lecture, we may say, was concerned mainly with some of the more important themes and technicalities of early Buddhist psychology. We shall, incidentally, be referring back to some of that material more than once in the course of the coming lectures. The second lecture in the course, on the psychology of spiritual development, was concerned much more directly than the first lecture was with the spiritual life. You may remember that we traced the ascent of humanity up the stages of the spiral from the round of existence, from Samsara, even to Nirvana. Today we come to our third lecture, our third subject, which is the Depth Psychology of the Yogacara. This evening we are concerned to some extent with psychological themes and technicalities, as we were in the first lecture, but we're also concerned, as we were in the second lecture, with the spiritual life itself. We are concerned with the first as subordinate to the second, as we shall see in due course. So we may say, broadly speaking, that this evening's lecture follows a sort of middle way, or middle course, between the type of subject matter we had in the first lecture and the type of subject matter we had in the second. Now a question which immediately arises, and which must have occurred to most of you when the title of the lecture was announced, "What is the Yogacara?" I'm sorry that in the course of the lectures we keep on having to have all these Sanskrit and Pali names and titles and so on, but until they become as it were naturalised in English, there's no other way. -

An Exploration of the Early One-True Dharmadhatu Thoughts---From

2019 9th International Conference on Education and Social Science (ICESS 2019) An Exploration of the Early One-True Dharmadhatu Thoughts----From Mind Only Chittamatra, Tantra to Huayen Theory Xiangjun Su Institute of Taoism and Religious Culture, Sichuan University, Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China 206877705@qq. com Keywords: One-true dharmadhatu; Mind only chittamatra; Tantra, Huayen theory; Harmony without obstacles Abstract: The concept of one-true Dharmadhatu originates from India Buddhism, and it appears both in Vijnapti-matrata and Tantra classics, approximately having the same meaning. Li tongxuan was the first one who introduced the concept of One-true Dharmadhatu into Huayen theory. Conformed with the thinking mode of Matter-mind-being Nonduality by Li Tongxuan, taking Fundamental Wisdom as its basis, One-true Dharmadhatu has such harmonious teaching characteristics as wisdom and earth being one, nature and things binging not different, and harmony without obstacles. Later, Chengguan, in his Wutai Mountain Period, explained One-true Dharmadhatu as Dharmadhatu Pure Wisdom, and combined it with Fazang’s Five Dharmadhatu thought, thus made it more philosophical. Introduction In China’s Huayen thoughts, One-true Dharmadhatu is an important concept. Since was introduced into Huayen theory by Li Tongxuan, One-true Dharmadhatu has appeared often in Chenguan’s works and the Huayen works of the following dynasties. Japanese scholar Xiaodaodaishan, Tanwan region researcher Hong Meizhen have discussed the concept of One-true Dharmadhatu in their works. [1]China Main Land scholar Liu Yuanyuan has discussed Li Tongxuan’s thoughts on One-true Dharmadhatu and its influences on Chengguan deeply, but it is not comprehensive, and also not involves in the thoughts of Chengguan. -

A Lesson from Borobudur

5 Changing perspectives on the relationship between heritage, landscape and local communities: A lesson from Borobudur Daud A. Tanudirjo, Jurusan Arkeologi, Fakultas Ilmu Budaya, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta Figure 1. The grandeur of the Borobudur World Heritage site has attracted visitors for its massive stone structure adorned with fabulous reliefs and stupas laid out in the configuration of a Buddhist Mandala. Source: Daud Tanudirjo. The grandeur of Borobudur has fascinated almost every visitor who views it. Situated in the heart of the island of Java in Indonesia, this remarkable stone structure is considered to be the most significant Buddhist monument in the Southern Hemisphere (Figure 1). In 1991, Borobudur 66 Transcending the Culture–Nature Divide in Cultural Heritage was inscribed on the World Heritage List, together with two other smaller stone temples, Pawon and Mendut. These three stone temples are located over a straight line of about three kilometres on an east-west orientation, and are regarded as belonging to a single temple complex (Figure 2). Known as the Borobudur Temple Compound, this World Heritage Site meets at least three criteria of the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention: (i) to represent a masterpiece of human creative genius, (ii) to exhibit an important interchange of human values over a span of time or within cultural area of the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts, town planning or landscape design, and (iii) to be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literacy works of outstanding universal value (see also Matsuura 2005).