Transfer and Countertransference in Frederic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geology and Ecology in the Nineteenth Century American Landscape Paintings of Frederic E

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2001 Volume II: Art as Evidence: The Interpretation of Objects Reading the Landscape: Geology and Ecology in the Nineteenth Century American Landscape Paintings of Frederic E. Church Curriculum Unit 01.02.01 by Stephen P. Broker Introduction This curriculum unit uses nineteenth century American landscape paintings to teach high school students about topics in geography, geology, ecology, and environmental science. The unit blends subject matter from art and science, two strongly interconnected and fully complementary disciplines, to enhance learning about the natural world and the interaction of humans in natural systems. It is for use in The Dynamic Earth (An Introduction to Physical and Historical Geology), Environmental Science, and Advanced Placement Environmental Science, courses I teach currently at Wilbur Cross High School. Each of these courses is an upper level (Level 1 or Level 2) science elective, taken by high school juniors and seniors. Because of heavy emphasis on outdoor field and laboratory activities, each course is limited in enrollment to eighteen students. The unit has been developed through my participation in the 2001 Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute seminar, "Art as Evidence: The Interpretation of Objects," seminar leader Jules D. Prown (Yale University, Professor of the History of Art, Emeritus). The "objects" I use in developing unit activities include posters or slides of studio landscape paintings produced by Frederic Church (1826-1900), America's preeminent landscape painter of the nineteenth century, completed during his highly productive years of the 1840s through the 1860s. Three of Church's oil paintings referred to may also be viewed in nearby Connecticut or New York City art museums. -

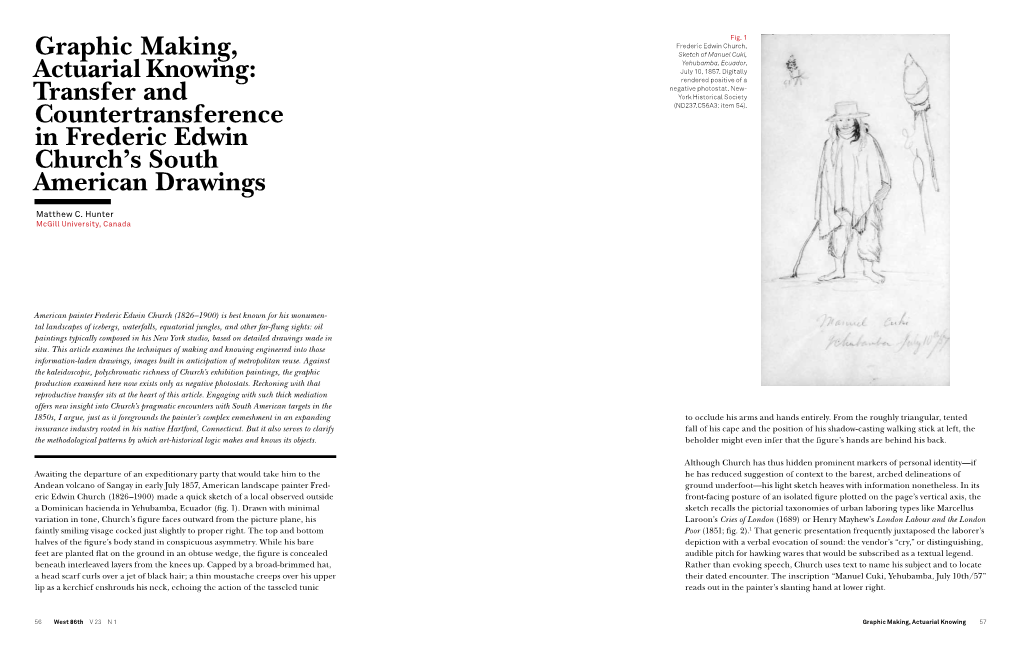

Frederic Edwin Church;

ES"SMITHS0NIAN~|NSTITUTI0N NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS S3iyvyan L I B R A R I E S SMITHSONIAN "INSTITUTION NO >- 1 B RAR I ES SMiTHSONlAN_INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI_NVINOSHliWS S3IHVyan_LIE SNI_MVIN0SH1IWS S3 I H VH a n_ ES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHillAIS S3iyvaan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOI SNI~NVINOSHims' S3iava9n~LlBRARIES SMITHSONIAN~INSTITUTION NOIiOiliSNI NVINOSHimS SHiyvyaH LIB _ .- - ^ ^- ^ 2: /:r?£^p> - /?^»^\ - ^ . - x.«^» - NOI Es'"SMITHS0NiAN_INSTITUTI0N'^N0linillSNI_NVIN0SHilWs'^S3 I avaan_LiBRAR I ES SMITHS0NIAN_INST1TUTI0N 3NI~NVIN0SHimS ~S3iyvaan~LIBRARlES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI^NVINOSHimS SSiavyaiT LIB I- " ^ <" z: H z _ W — (/I _ CO *^ E ES"'SMITHSONiAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHimS S3iyvaan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOI / o SNI NVIN0SHilWs'"s3 lavaan^LIBRAR IEs"'SMITHSONIAN'"lNSTITUTlON"NOIiniliSNrNVINOSHii;Ms'"s3 I yvyail^LIE H - - „, t/, CO \ ? C/5 ± _ vji NWNOSHims S3iyvyan libraries Smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi nvinoshiiiais S3 i hvh a n li br/ -' c/J z; c^ z w z .... z ^.. CO ^ ^ ^^ _ _ _ Z CO s"'smithsonian institution NoiiniiiSNi NviN0SHiiws"'s3iavy an libraries smithsonian_institution Noiin libr I NoiiniiiSNi~'NviNOSHims S3iavaan ji"'NviN0SHiiiAis^S3r-~ 1 y vd a n'^Li B RAR es^smithsonian"'institution_ — — — ^ — CD LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOlif S' SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION" NOIiniliSNI ~NVINOSHimS -- S3iyvyan — -- (ft '' •" ^ CO z CO z CO z CO z Ml NVINOSHilWS S3iavyan_LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN_INSTITUTION N0liniliSNI_NVIN0SHimS_S3 I y Vy a n_LI B R S SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNrNVINOSHimS S3iyvyan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIlf N0liniliSNI_^NVINOSHimS^^S3 iyvyan_^LIBR Nl~NVIN0SHilWS,_S3 I y Vd 3 n~LI B R AR I ES^SMITHSONIAN "INSTITUTION.. :S SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHiltNS S3iyVaan LIBRARIES SMITHSONIAN_ INSTITUTION NOlif FREDERIC EDWIN CHURCH ^ATALQiSUr': J}a9T FREDERIC EDWIN CHURCH 67- The Andes of Ecuador FREDERIC EDWIN CHURCH An Exhibition Organized by the National Collection of Fine Arts Smithsonian Institution, Washingtoji, D. -

Thomas J. Watson Library Digital Collections | the Metropolitan

The Metropolitan Museum of Art AiU 19th CENTURY AMERICAN LANDSCAPE Queens County Art and Cultural Center November 10-December 10,1972 The Metropolitan Museum of Art January—February 1973 Memorial Art Gallery of The University of Rochester- March-April 1973 An exhibition from The Metropolitan Museum of Art made possible by grants from the New York State Council on the Arts and the National Endowment on the Arts. I>t is indeed a great selected the paintings, wrote the introduc honor for the Metropolitan Museum of tion and prepared the catalogue entries Art to initiate the Queens County Art with the help of Assistant Curators and Cultural Center with the exhibition, Natalie Spassky and Lewis Sharp, as well Nineteenth Century American as Janet Miller, Departmental Secretary. Landscape. Congratulations to Borough Special thanks go to Edward Bloodgood, President Donald R. Manes; Parks, Roland Brand and Sandy Canzoneri Recreation and Cultural Affairs for installing the exhibition. The Administrator August Heckscher; Com catalogue was designed by John Murello missioner of Cultural Affairs, Phyllis in cooperation with Stuart Silver, Robinson, the staff of the Cultural Administrator of the Museum's Design Center, and the many Queens residents Department. Bret Waller, Museum who have worked so long and hard to Educator in charge of Public Education, achieve this moment. I sincerely, hope assisted in the production of the catalogue that this will prove an auspicious and in providing the liaison with beginning, and that many fine exhibitions Rochester. Among the countless other and programs will follow. 'unsung heros' are those in the Registrar's Nineteenth Century Office responsible for all packing and American Landscape has been coordi shipping arrangements, and in the nated by the Department of Community Security Department providing the excel Programs and made possible by grants lent guardianship at the Queens County from the New York State Council on the Art and Cultural Center. -

A Pedagogical Summary of the Hudson River School Project

A PEDAGOGICAL SUMMARY OF THE HUSDON RIVER SCHOOL PROJECT. (Not for circulation. A report for Gerry Rose, Leesburg, Va. 10/12/2008) by Pierre Beaudry INTRODUCTION: THE INSIGHT PRINCIPLE. “{True genius accepts its duty, and will not rest short of the highest truth of his age.}” Theodore Winthrop. Frederic Edwin Church, Heart of the Andes, 1859. During a period of about fifty years (1826-1876) the Hudson River School of landscape painting had the purpose of initiating an American Renaissance in art and of establishing a cultural revolution in the American social fabric as a whole. If it did not succeed, it was not because its landscape artists did not have the required genius to do it, 1 but because the American population did not have the required { insight principle } to discover it for what it was when it came, and was unable to nurture it and fight back when it came under systematic attacks by the British Empire. This raises the question: how can an artistic renaissance be made successful in America and how can it be made to last? It is not the object of this report to answer this question, per se, but merely to force awareness of the question with respect to what Lyn identified as the { insight Principle .} (Appropriate quote needed) For example, the truth that was conveyed by the first exhibitions of The Course of Empire (1836) by Thomas Cole, or the Heart of the Andes (1859) by Frederic Church was not seized because the population was not ready to fight public opinion and be truthful as was required of a people that had just fought and won its independence against British imperialism. -

Neither Land Nor Water: Martin Johnson Heade

NEITHER LAND NOR WATER: MARTIN JOHNSON HEADE, FREDERIC EDWIN CHURCH, AND AMERICAN LANDSCAPE PAINTING IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY BY Elizabeth T. Holmstead ABSTRACT Martin Johnson Heade and Frederic Edwin Church had a close personal relationship, shared a studio for more than a decade, and maintained a correspondence that lasted nearly forty years. Church was better known and certainly more successful commercially than Heade, but despite their close proximity DQG+HDGH¶V personal and professional admiration for Church, Heade should not be seen as an imitator of Church. +HDGH¶Vpaintings are a departure from &KXUFK¶VZRUN in both form and content. In particular, a study of +HDGH¶V many marsh paintings reveals that, ZKLOH+HDGHXVHGVRPHRI&KXUFK¶VFRPSRVLWLonal elements, +HDGH¶V preparation, working method, purpose, and message to his audience are quite different from those of Church. +HDGH¶Vmarsh paintings make their own unique contribution to the history of American art. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS With Grateful Thanks to Jeffrey R. Holmstead and Heather N. Hardy iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................. iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS .......................................................................................................... v CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... -

19Th Century Painters: Hudson River School Hudsonrivervalley.Com

Map & Guide Series Na lley tion Va al Hudson River Valley r H e e v r i i 19th Century Painters: t National Heritage Area, New York R a g n e o A hudsonrivervalley.com s r d e u a Hudson River School H rom the 1820s through the end of the century, the natural wonders of the Hudson River Valley kindled one of the most significant achievements in the nation’s cultural history—the development Fof a style of painting that expressed the American character. In 1825 the dramatic scenery of the Hudson River Valley inspired a young artist, Thomas Cole, to create the first paintings of the American landscape in the new, Romantic style. What began as a casual group of painters eager to capture the beauty of upstate New York grew to become a school of artists who traveled the country and even the world producing some of the masterpieces of American art. Paintings shown in this brochure can be seen in the Hudson River Valley at the indicated heritage sites. View of Tappan Zee from Lovat Hill, Jasper F. Cropsey, 1887, Newington-Cropsey Foundation, Hastings-on-Hudson Please see the map side of this brochure for information about collections of Hudson River paintings. A New Artistic Philosophy for tourism. Summer retreats appeared American Academy of the Fine Arts, who The mid-1820s was a remarkable time in up and down the Hudson River. The bought the painting and spread the news the Hudson River Valley. The Catskill valley attracted entrepreneurs, tourists, about the new young painter on the New Mountain House, the country’s first and travelers eager to share in the wealth, York art scene. -

Sanford Robinson Gifford

AN ARTIST’S LEGACY AND AN ARTIST’S MICHAEL ALTMAN is a fine-art dealer who special- A DEALER’S ADMIRATION AN ARTIST’S LEGACY AND his catalog, published to accompany an izes in nineteenth- and twentieth-century American exhibition of more than forty notable paintings. For more than twenty-five years he has A DEALER’S ADMIRATION paintings by Sanford Robinson Gifford advised both private collectors and public institu- T at Michael Altman Fine Art, provides an intimate tions in building and enriching their collections. His depiction of the artist and offers further proof gallery is located in a private townhouse on Manhat- Paintings by tan’s Upper East Side. as to why he is known by many to be the most accomplished luminist painter of the nineteenth KEVIN J. AVERY is a senior research scholar and a for- century. The works in the exhibition are para- mer associate curator at the Metropolitan Museum Sanford Robinson Gifford mount examples of the artist’s technical skill and of Art and an adjunct professor in the art depart- of the exquisite representations he made of his ment of Hunter College, City University of New surroundings. Gifford’s forte lies in his ability to York. Dr. Avery received his B.A. in art history from from Important American Collections Fordham University and his M.A. and Ph.D. degrees capture the moment in its magnificence, whether from Columbia University, where he wrote his dis- it is the dawn breaking over the Hudson Valley or sertation on the panorama and its manifestations in a canal in Venice just before sunset. -

A Tlapalizquixochitl Tree

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2009 A TLAPALIZQUIXOCHITL TREE Christopher Mahonski Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Art and Design Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1838 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This writing was done in correlation with my thesis show, The Void, the Coach and the Future. A TLAPALIZQUIXOCHITL TREE1 1 Tsouras, Peter G. Montezuma:Warlord of the Aztecs, Potomac Books, Washington D.C., 2005, p 33 “In 1503 he heard of a small, rare tlapalizquixochitl tree, belonging to Malinal, the Mixtec king of Tlachquiauhco. In a land already famous for its fruit trees, the king had imported this tree at great cost for its blossoms, which were of exquisite fragrance and incomparable beauty. Motecuhzoma was determined to have it, even though Tenochtitlan's cold climate was unsuited for such a tropical plant. Nothing of such beauty could exist without his possessing it. Motecuhzoma demanded it of Malinal, who refused. That triggered a Mexica attack, Malinal and many of his people died defending their city, which was annexed to the empire along with all its subject towns. The tree was uprooted and died.” CONTENTS I. Church in the Jungle II. III. Autobiographical IV. A Leopard V. The Landscape VI. -

On the Afternoons of February I 5, I 6, I 7 An" 18

NEW YORK AND ONTHE AFTERNOONSOF FEBRUARYI 5, I 6, I 7 AN" 18 CONDITIONS OF SALE I. The highest Bidder to be the Buyer, and if any dis- pute arise between two or more Bidders, the Lot so in dispute shall be immediately put up again and re-sold. 2. The Purchasers to give their names and addresses, and to pay down a cash deposit, or the whole of the Purchase- money zy required, in default of which the Lot or Lots so purchased to be immediately put up again and re-sold. 3. The Lotsto be taken away at the Buyer’s Expense and Risk ujon the conclusion of the Sale. and the remainder of the Purchase-money to be absolutely paid or otherwise settled for to the satisfaction of the Auctioneer, on or before delivery ; in default of which the undersigned will not hold themselves responsible if the Lots be lost, stolen, damaged, or destroyed, but they will be left at the SOIC risk of the Purchaser. 4. The sale of any article is not to be set aside on account of any error in the descr$tion, or imjerfecîion. A¿¿ articles are exposed for PubZic Exhibition one 01 more days, and are sold just as they are without recourse, S. To prevent inaccuracy in delivery and inconvenience --. in the settlement of the purchases, noLot can, on any account, be removed during the sale. 6. Upon failure to comply with the above condition”, ,î%G money deposited in part payment shall be forfeited ; all Lots uncleared within two days from conclusion of sale shall be re-sold by public or private Sale, without further notice, andthe deficiency (if any)attending such re-sale shall be made good by the defaulter at this Sale, together with allcharges attending the same. -

The Andes and the Amazon

The Andes And The Amazon By James Orton THE ANDES AND THE AMAZON. CHAPTER I. Guayaquil.— First and Last Impressions.— Climate.— Commerce.— The Malecon.— Glimpse of the Andes.— Scenes on the Guayas.— Bodegas.— Mounted for Quito.— La Mona.— A Tropical Forest. Late in the evening of the 19th of July, 1867, the steamer "Favorita" dropped anchor in front of the city of Guayaquil. The first view awakened visions of Oriental splendor. Before us was the Malecon, stretching along the river, two miles in length—at once the most beautiful and the most busy street in the emporium of Ecuador. In the centre rose the Government House, with its quaint old tower, bearing aloft the city clock. On either hand were long rows of massive, apparently marble, three-storied buildings, each occupying an entire square, and as elegant as they were massive. Each story was blessed with a balcony, the upper one hung with canvas curtains now rolled up, the other protruding over the sidewalk to form a lengthened arcade like that of the Rue de Rivoli in imperial Paris. In this lower story were the gay shops of Guayaquil, filled with the prints, and silks, and fancy articles of England and France. As this is the promenade street as well as the Broadway of commerce, crowds of Ecuadorians, who never do business in the evening, leisurely paced the magnificent arcade; hatless ladies sparkling with fire-flies instead ofdiamonds, and far more brilliant than koh-i-noors, swept the pavement with their long trains; martial music floated on the gentle breeze from the barracks or some festive hall, and a thousand gas-lights along the levee and in the city, doubling their number by reflection from the river, betokened wealth and civilization. -

Essay on the Geography of Plants

Essay on the Geography of Plants Essay on the Geography of Plants alexander von humboldt and aime´ bonpland Edited with an Introduction by Stephen T. Jackson Translated by Sylvie Romanowski the university of chicago press :: chicago and london Stephen T. Jackson is professor of botany and ecology at the University of Wyoming. Sylvie Romanowski is professor of French at Northwestern University and author of Through Strangers’ Eyes: Fictional Foreigners in Old Regime France. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2009 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 2008 Printed in the United States of America 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 1 2 3 4 5 isbn-13: 978-0-226-36066-9 (cloth) isbn-10: 0-226-36066-0 (cloth) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Humboldt, Alexander von, 1769–1859. [Essai sur la géographie des plantes. English] Essay on the geography of plants / Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland ; edited with an introduction by Stephen T. Jackson ; translated by Sylvie Romanowski. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. isbn-13: 978-0-226-36066-9 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-226-36066-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Phytogeography. 2. Plant ecology. 3. Physical geography. I. Bonpland, Aimé, 1773–1858. II. Jackson, Stephen T., 1955– III. Romanowski, Sylvie. IV. Title. qk101 .h9313 2009 581.9—dc22 2008038315 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ansi z39.48-1992. -

The Hudson River School, the Sleeping Giant of an American Renaissance

From the desk of Pierre Beaudry ₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪ THE HUDSON RIVER SCHOOL, THE SLEEPING GIANT OF AN AMERICAN RENAISSANCE ₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪₪ by Pierre Beaudry, 3/22/2008 INTRODUCTION: THE ART OF JAMES FENIMORE COOPER. The Hudson River School of painting was composed of a very diversified grouping of artists that reflected, in different degrees of advancement, the coming to maturity of cultural American exceptionalism, which was to define, by the creation of a typical American culture, a new and more advanced form of Western Civilization than was reflected in Europe at that time. The purpose of this movement as a whole was aimed at not only establishing on these shores a culture of progress in human development, but, also, to strike a definite blow to the dominating form of European oligarchical counterculture of entertainment and pessimism that was infecting the world during that period. However, the movement was sabotaged by a combination of British and French imperial operations and the Hudson River School project was destroyed by the middle of the 1870’s only to be replaced by the cowboy counterculture. America has not, to this day, recovered from that humiliating abasement. It is important, here, to identify the historical specificity of the Hudson River School within the larger context of the American experiment. The fact that a significant number of the artists of this movement came from Mid-Western and New England families, which were reared in rural America with direct ancestry of puritan optimism, represents a major aspect of the cultural characteristic of this movement and of the 1 American character in general.