Sixty Years' Memories of Art and Artists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hudson River School

Hudson River School 1796 1800 1801 1805 1810 Asher 1811 Brown 1815 1816 Durand 1820 Thomas 1820 1821 Cole 1823 1823 1825 John 1826 Frederick 1827 1827 1827 1830 Kensett 1830 Robert 1835 John S Sanford William Duncanson David 1840 Gifford Casilear Johnson Jasper 1845 1848 Francis Frederic Thomas 1850 Cropsey Edwin Moran Worthington Church Thomas 1855 Whittredge Hill 1860 Albert 1865 Bierstadt 1870 1872 1875 1872 1880 1880 1885 1886 1910 1890 1893 1908 1900 1900 1908 1908 1902 Compiled by Malcolm A Moore Ph.D. IM Rocky Cliff (1857) Reynolds House Museum of American Art The Beeches (1845) Metropolitan Museum of Art Asher Brown Durand (1796-1886) Kindred Spirits (1862) Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art The Fountain of Vaucluse (1841) Dallas Museum of Art View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm - the Oxbow. (1836) Metropolitan Museum of Art Thomas Cole (1801-48) Distant View of Niagara Falls (1836) Art Institute of Chicago Temple of Segesta with the Artist Sketching (1836) Museum of Fine Arts, Boston John William Casilear (1811-1893) John Frederick Kensett (1816-72) Lake George (1857) Metropolitan Museum of Art View of the Beach at Beverly, Massachusetts (1869) Santa Barbara Museum of Art David Johnson (1827-1908) Natural Bridge, Virginia (1860) Reynolda House Museum of American Art Lake George (1869) Metropolitan Museum of Art Worthington Whittredge (1820-1910) Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823-1900) Indian Encampment (1870-76) Terra Foundation for American Art Starrucca Viaduct, Pennsylvania (1865) Toledo Museum of Art Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823-1880) Robert S Duncanson (1821-1902) Whiteface Mountain from Lake Placid (1866) Smithsonian American Art Museum On the St. -

Delaroche's Napoleon in His Study

Politics, Prints, and a Posthumous Portrait: Delaroche’s Napoleon in his Study Alissa R. Adams For fifteen years after he was banished to St. Helena, Na- By the time Delaroche was commissioned to paint Na- poleon Bonaparte's image was suppressed and censored by poleon in his Study he had become known for his uncanny the Bourbon Restoration government of France.1 In 1830, attention to detail and his gift for recreating historical visual however, the July Monarchy under King Louis-Philippe culture with scholarly devotion. Throughout the early phase lifted the censorship of Napoleonic imagery in the inter- of his career he achieved fame for his carefully rendered est of appealing to the wide swath of French citizens who genre historique paintings.2 These paintings carefully repli- still revered the late Emperor—and who might constitute cated historical details and, because of this, gave Delaroche a threat if they were displeased with the government. The a reputation for creating meticulous depictions of historical result was an outpouring of Napoleonic imagery including figures and events.3 This reputation seems to have informed paintings, prints, and statues that celebrated the Emperor the reception of his entire oeuvre. Indeed, upon viewing an and his deeds. The prints, especially, hailed Napoleon as a oval bust version of the 1845 Napoleon at Fontainebleau hero and transformed him from an autocrat into a Populist the Duc de Coigny, a veteran of Napoleon’s imperial army, hero. In 1838, in the midst of popular discontent with Louis- is said to have exclaimed that he had “never seen such a Philippe's foreign and domestic policies, the Countess of likeness, that is the Emperor himself!”4 Although the Duc Sandwich commissioned Paul Delaroche to paint a portrait de Coigny’s assertion is suspect given the low likelihood of of Napoleon entitled Napoleon in his Study (Figure 1) to Delaroche ever having seen Napoleon’s face, it eloquently commemorate her family’s connection to the Emperor. -

Daxer & Marschall 2015 XXII

Daxer & Marschall 2015 & Daxer Barer Strasse 44 - D-80799 Munich - Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 - Fax +49 89 28 17 57 - Mobile +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] - www.daxermarschall.com XXII _Daxer_2015_softcover.indd 1-5 11/02/15 09:08 Paintings and Oil Sketches _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 1 10/02/15 14:04 2 _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 2 10/02/15 14:04 Paintings and Oil Sketches, 1600 - 1920 Recent Acquisitions Catalogue XXII, 2015 Barer Strasse 44 I 80799 Munich I Germany Tel. +49 89 28 06 40 I Fax +49 89 28 17 57 I Mob. +49 172 890 86 40 [email protected] I www.daxermarschall.com _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 3 10/02/15 14:04 _Daxer_2015_bw.indd 4 10/02/15 14:04 This catalogue, Paintings and Oil Sketches, Unser diesjähriger Katalog Paintings and Oil Sketches erreicht Sie appears in good time for TEFAF, ‘The pünktlich zur TEFAF, The European Fine Art Fair in Maastricht, European Fine Art Fair’ in Maastricht. TEFAF 12. - 22. März 2015, dem Kunstmarktereignis des Jahres. is the international art-market high point of the year. It runs from 12-22 March 2015. Das diesjährige Angebot ist breit gefächert, mit Werken aus dem 17. bis in das frühe 20. Jahrhundert. Der Katalog führt Ihnen The selection of artworks described in this einen Teil unserer Aktivitäten, quasi in einem repräsentativen catalogue is wide-ranging. It showcases many Querschnitt, vor Augen. Wir freuen uns deshalb auf alle Kunst- different schools and periods, and spans a freunde, die neugierig auf mehr sind, und uns im Internet oder lengthy period from the seventeenth century noch besser in der Galerie besuchen – bequem gelegen zwischen to the early years of the twentieth century. -

The Artist and the American Land

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications Sheldon Museum of Art 1975 A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land Norman A. Geske Director at Sheldon Memorial Art Gallery, University of Nebraska- Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs Geske, Norman A., "A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land" (1975). Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications. 112. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sheldonpubs/112 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sheldon Museum of Art at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sheldon Museum of Art Catalogues and Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME I is the book on which this exhibition is based: A Sense at Place The Artist and The American Land By Alan Gussow Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 79-154250 COVER: GUSSOW (DETAIL) "LOOSESTRIFE AND WINEBERRIES", 1965 Courtesy Washburn Galleries, Inc. New York a s~ns~ 0 ac~ THE ARTIST AND THE AMERICAN LAND VOLUME II [1 Lenders - Joslyn Art Museum ALLEN MEMORIAL ART MUSEUM, OBERLIN COLLEGE, Oberlin, Ohio MUNSON-WILLIAMS-PROCTOR INSTITUTE, Utica, New York AMERICAN REPUBLIC INSURANCE COMPANY, Des Moines, Iowa MUSEUM OF ART, THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY, University Park AMON CARTER MUSEUM, Fort Worth MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON MR. TOM BARTEK, Omaha NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, Washington, D.C. MR. THOMAS HART BENTON, Kansas City, Missouri NEBRASKA ART ASSOCIATION, Lincoln MR. AND MRS. EDMUND c. -

America Past

A Teacher’s Guide to America Past Sixteen 15-minute programs on the social history of the United States for high school students Guide writer: Jim Fleet Series consultant: John Patrick 01987 KRMA-W, Denver, Colorado and Agency for Instructional Technology Bloomington, Indiana AH rights reserved. This guide, or any part of it, may not be reproduced without written permission. Review questions in this guide maybe reproduced and distributed free to students. All inquiries should be addressed to: Agency for Instructional Technology Box A Bloomington, Indiana 47402 Table Of Contents Introduction To The AmericaPastSeries . 4 About Jim Fleet . ...!.... 5 America Past: An Overview . 5 How To Use This Guide . 5 Sources On People And Places In America Past . 5 Programs I. New Spain . 6 2. New France . 9 3. The Southern Colonies . 11 4. New England Colonies . 13 5. Canals and Steamboats . 16 6. Roads and Railroads, . .19 7. The Artist’s View . ... ..,.. 22 8. The Writer’s View . ...25 9. The Abolitionists . ...27 10. The Role of Women . ...29 ll. Utopias . ...31 12. Religion . ...33 13. Social Life . ...35 14. Moving West . ...38 15. The Industrial North . ...41 16. The Antebellum South . ...43 Textbook Correlation Chart . ...46 AnswerKey . ...48 Introduction To The America Past Series Over the past thirty years, it has been my experience that most textbooks and visual aids do an adequate job of cover- ing the political and economic aspects of American history UntiI recently however, scant attention has been given to social history. America Past was created to fill that gap. Some programs, such as those on religion and utopias, elaborate upon topics that may receive only a paragraph or two in many texts. -

NHHS Consuming Views

CONTRIBUTORS Heidi Applegate wrote an introductory essay for Hudson River Janice T. Driesbach is the director of the Sheldon Memorial Art School Visions: The Landscapes of Sanford R. Gifford (Metro- Gallery and Sculpture Garden at the University of Nebraska- politan Museum of Art, 2003). Formerly of the National Lincoln. She is the author of Direct from Nature: The Oil Gallery of Art, she is now a doctoral candidate in art history at Sketches of Thomas Hill (Yosemite Association in association Columbia University. with the Crocker Art Museum, 1997). Wesley G. Balla is director of collections and exhibitions at the Donna-Belle Garvin is the editor of Historical New Hampshire New Hampshire Historical Society. He was previously curator and former curator of the New Hampshire Historical Society. of history at the Albany Institute of History and Art. He has She is coauthor of the Society’s On the Road North of Boston published on both New York and New Hampshire topics in so- (1988), as well as of the catalog entries for its 1982 Shapleigh cial and cultural history. and 1996 Champney exhibitions. Georgia Brady Barnhill, the Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Elton W. Hall produced an exhibition and catalog on New Bed- Graphic Arts at the American Antiquarian Society, is an au- ford, Massachusetts, artist R. Swain Gifford while curator of thority on printed views of the White Mountains. Her “Depic- the Old Dartmouth Historical Society. Now executive director tions of the White Mountains in the Popular Press” appeared in of the Early American Industries Association, he has published Historical New Hampshire in 1999. -

As Time Passes Over the Land

s Time Passes over theLand A White Mountain Art As Time Passes over the Land is published on the occasion of the exhibition As Time Passes over the Land presented at the Karl Drerup Art Gallery, Plymouth State University, Plymouth, NH February 8–April 11, 2011 This exhibition showcases the multifaceted nature of exhibitions and collections featured in the new Museum of the White Mountains, opening at Plymouth State University in 2012 The Museum of the White Mountains will preserve and promote the unique history, culture, and environmental legacy of the region, as well as provide unique collections-based, archival, and digital learning resources serving researchers, students, and the public. Project Director: Catherine S. Amidon Curator: Marcia Schmidt Blaine Text by Marcia Schmidt Blaine and Mark Green Edited by Jennifer Philion and Rebecca Chappell Designed by Sandra Coe Photography by John Hession Printed and bound by Penmor Lithographers Front cover The Crawford Valley from Mount Willard, 1877 Frank Henry Shapleigh Oil on canvas, 21 x 36 inches From the collection of P. Andrews and Linda H. McLane © 2011 Mount Washington from Intervale, North Conway, First Snow, 1851 Willhelm Heine Oil on canvas, 6 x 12 inches Private collection Haying in the Pemigewasset Valley, undated Samuel W. Griggs Oil on canvas, 18 x 30 inches Private collection Plymouth State University is proud to present As Time Passes over the about rural villages and urban perceptions, about stories and historical Land, an exhibit that celebrates New Hampshire’s splendid heritage of events that shaped the region, about environmental change—As Time White Mountain School of painting. -

American Paintings, Furniture & Decorative Arts

AMERICAN PAINTINGS, FURNITURE & DECORATIVE ARTS INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF FRANK AND CLAIRE TRACY GLASER Tuesday, October 8, 2019 NEW YORK AMERICAN PAINTINGS, FURNTURE & DECORATIVE ARTS INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF FRANK AND CLAIRE TRACY GLASER AUCTION Tuesday, October 8, 2019 at 10am EXHIBITION Friday, October 4, 10am – 5pm Saturday, October 5, 10am – 5pm Sunday, October 6, Noon – 5pm LOCATION Doyle 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalog: $10 The Marian Sulzberger Heiskell & Andrew Heiskell Collection Doyle is honored to present The Marian Sulzberger Heiskell and Andrew Heiskell Collection in select auctions throughout the Fall season. A civic leader and philanthropist, Marian championed outdoor community spaces across AMERICAN New York and led a nonprofit organization responsible for restoring the 42nd Street theatres. She was instrumental in the 1972 campaign PAINTINGS, SCULPTURE & PRINTS to create the Gateway National Recreation Area, a 26,000-acre park with scattered beaches and wildlife refuges around the entrance to the New York-New Jersey harbor. For 34 years, she worked as a Director of The New York Times, where her grandfather, father, husband, brother, nephew and grand-nephew served as successive publishers. Her work at the newspaper focused on educational projects. In 1965, Marian married Andrew Heiskell, the Chairman of Time Inc., whose philanthropies included the New York Public Library. The New York Times The New York Property from The Marian Sulzberger Heiskell and Andrew Heiskell Collection comprises lots 335-337, 345-346, 349, 354 in the October 8 auction. Additional property from the Collection will be offered in the sales of Fine Paintings (Oct 15), Prints & Multiples (Oct 22), English & Continental Furniture & Old Master Paintings (Oct 30), Impressionist & Modern Art (Nov 6), Post-War & Contemporary Art (Nov 6), Books, Autographs & Maps (Nov 12), Bill Cunningham for Doyle at Home (Nov 26) and Photographs (Dec 11). -

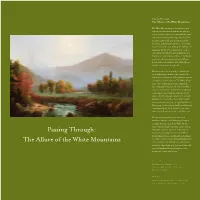

Passing Through: the Allure of the White Mountains

Passing Through: The Allure of the White Mountains The White Mountains presented nineteenth- century travelers with an American landscape: tamed and welcoming areas surrounded by raw and often terrifying wilderness. Drawn by the natural beauty of the area as well as geologic, botanical, and cultural curiosities, the wealthy began touring the area, seeking the sublime and inspiring. By the 1830s, many small-town tav- erns and rural farmers began lodging the new travelers as a way to make ends meet. Gradually, profit-minded entrepreneurs opened larger hotels with better facilities. The White Moun- tains became a mecca for the elite. The less well-to-do were able to join the elite after midcentury, thanks to the arrival of the railroad and an increase in the number of more affordable accommodations. The White Moun- tains, close to large East Coast populations, were alluringly beautiful. After the Civil War, a cascade of tourists from the lower-middle class to the upper class began choosing the moun- tains as their destination. A new style of travel developed as the middle-class tourists sought amusement and recreation in a packaged form. This group of travelers was used to working and commuting by the clock. Travel became more time-oriented, space-specific, and democratic. The speed of train travel, the increased numbers of guests, and a widening variety of accommodations opened the White Moun- tains to larger groups of people. As the nation turned its collective eyes west or focused on Passing Through: the benefits of industrialization, the White Mountains provided a nearby and increasingly accessible escape from the multiplying pressures The Allure of the White Mountains of modern life, but with urban comforts and amenities. -

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst

The Complete Poetry of James Hearst THE COMPLETE POETRY OF JAMES HEARST Edited by Scott Cawelti Foreword by Nancy Price university of iowa press iowa city University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright ᭧ 2001 by the University of Iowa Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Sara T. Sauers http://www.uiowa.edu/ϳuipress No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The publication of this book was generously supported by the University of Iowa Foundation, the College of Humanities and Fine Arts at the University of Northern Iowa, Dr. and Mrs. James McCutcheon, Norman Swanson, and the family of Dr. Robert J. Ward. Permission to print James Hearst’s poetry has been granted by the University of Northern Iowa Foundation, which owns the copyrights to Hearst’s work. Art on page iii by Gary Kelley Printed on acid-free paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hearst, James, 1900–1983. [Poems] The complete poetry of James Hearst / edited by Scott Cawelti; foreword by Nancy Price. p. cm. Includes index. isbn 0-87745-756-5 (cloth), isbn 0-87745-757-3 (pbk.) I. Cawelti, G. Scott. II. Title. ps3515.e146 a17 2001 811Ј.52—dc21 00-066997 01 02 03 04 05 c 54321 01 02 03 04 05 p 54321 CONTENTS An Introduction to James Hearst by Nancy Price xxix Editor’s Preface xxxiii A journeyman takes what the journey will bring. -

N E W S L E T T E R

N E W S L E T T E R Volume 55, Nos. 3 & 4 Fall 2018 Saco River, North Conway, Benjamin Champney (1817–1907), oil on canvas, 1874. Champney described the scenery along the Saco River, with its “thousand turns and luxuriant trees,” as “a combination of the wild and cultivated, the bold and graceful.” New Hampshire Historical Society. Documenting the Life and Work of Benjamin Champney The recent purchase of a collection of family papers some of the artist’s descendants live today. Based on adds new depth to the Society’s already strong evidence within the collection, these papers appear to resources documenting the life and career of influential have been acquired around 1960 by University of New White Mountain artist Benjamin Champney. A native Hampshire English professor William G. Hennessey of New Ipswich, Champney lived with his wife, from the estate or heirs of Benjamin Champney’s Mary Caroline (“Carrie”), in Woburn, Massachusetts, daughter, Alice C. Wyer of Woburn, the recipient of near his Boston studio, but spent summers in North many of the letters. Conway, producing and selling paintings to tourists. The collection also includes handwritten poems by The new collection includes 120 letters, some from Benjamin Champney, photographs of his Guatemalan the artist and others from his father (also named relatives, a photograph of Carrie Champney, and a Benjamin); from his brother Henry Trowbridge diary she kept during the couple’s 1865 trip to Europe. Champney; and from his son, Kensett Champney, the latter writing from his home in Guatemala, where (continued on page 4) New Hampshire Historical Society Newsletter Page 2 Fall 2018 President’s Message Earlier this year the New Hampshire Center for Public Policy Studies closed its doors. -

Geology and Ecology in the Nineteenth Century American Landscape Paintings of Frederic E

Curriculum Units by Fellows of the Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute 2001 Volume II: Art as Evidence: The Interpretation of Objects Reading the Landscape: Geology and Ecology in the Nineteenth Century American Landscape Paintings of Frederic E. Church Curriculum Unit 01.02.01 by Stephen P. Broker Introduction This curriculum unit uses nineteenth century American landscape paintings to teach high school students about topics in geography, geology, ecology, and environmental science. The unit blends subject matter from art and science, two strongly interconnected and fully complementary disciplines, to enhance learning about the natural world and the interaction of humans in natural systems. It is for use in The Dynamic Earth (An Introduction to Physical and Historical Geology), Environmental Science, and Advanced Placement Environmental Science, courses I teach currently at Wilbur Cross High School. Each of these courses is an upper level (Level 1 or Level 2) science elective, taken by high school juniors and seniors. Because of heavy emphasis on outdoor field and laboratory activities, each course is limited in enrollment to eighteen students. The unit has been developed through my participation in the 2001 Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute seminar, "Art as Evidence: The Interpretation of Objects," seminar leader Jules D. Prown (Yale University, Professor of the History of Art, Emeritus). The "objects" I use in developing unit activities include posters or slides of studio landscape paintings produced by Frederic Church (1826-1900), America's preeminent landscape painter of the nineteenth century, completed during his highly productive years of the 1840s through the 1860s. Three of Church's oil paintings referred to may also be viewed in nearby Connecticut or New York City art museums.